Andy Warhol Peers Into Keith Haring’s Special World

This story is part of a collection celebrating the best—and wildest—Warhol conversations from the Interview archives.

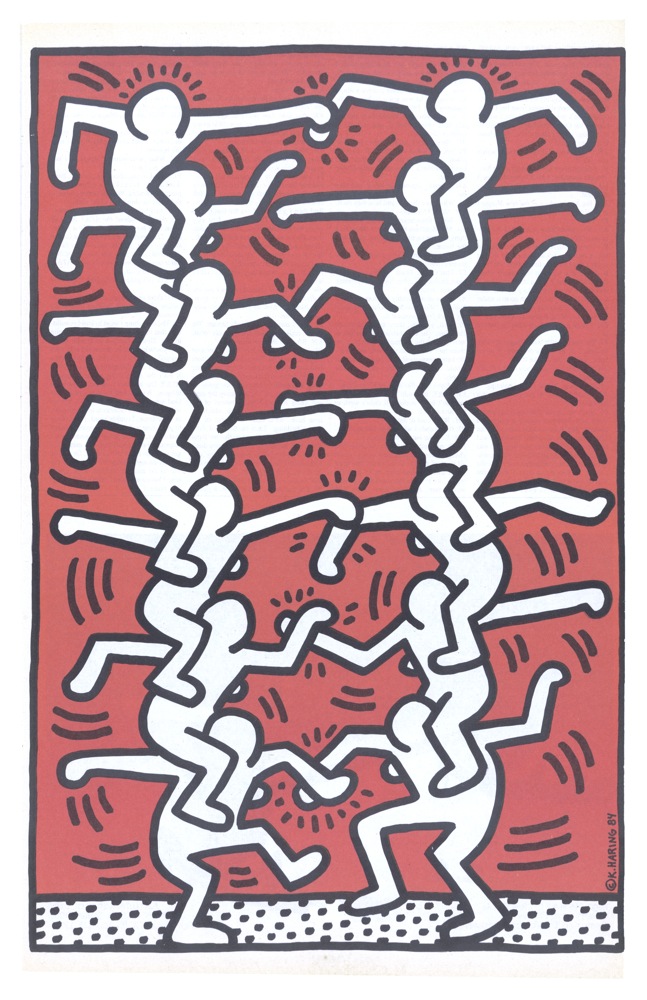

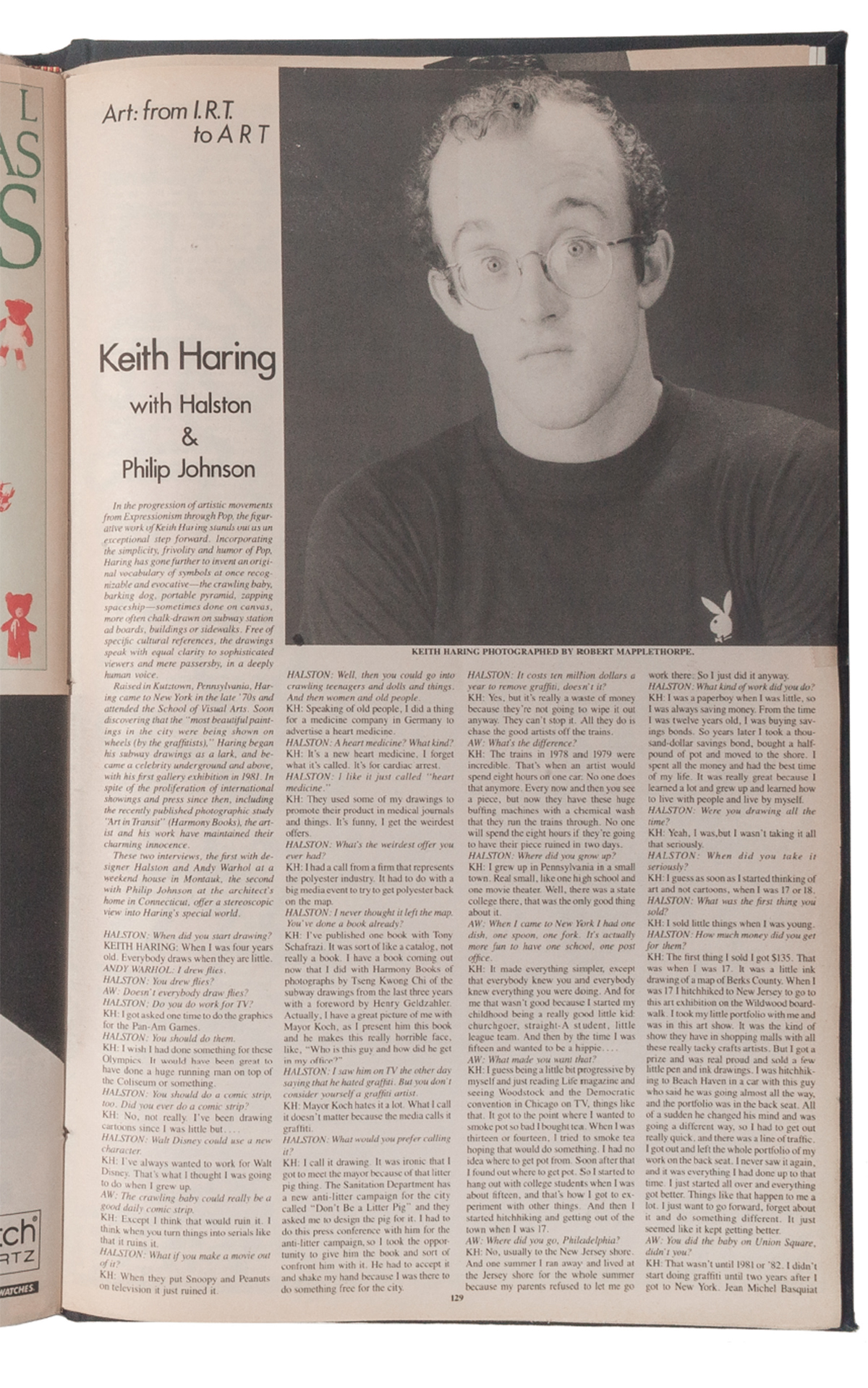

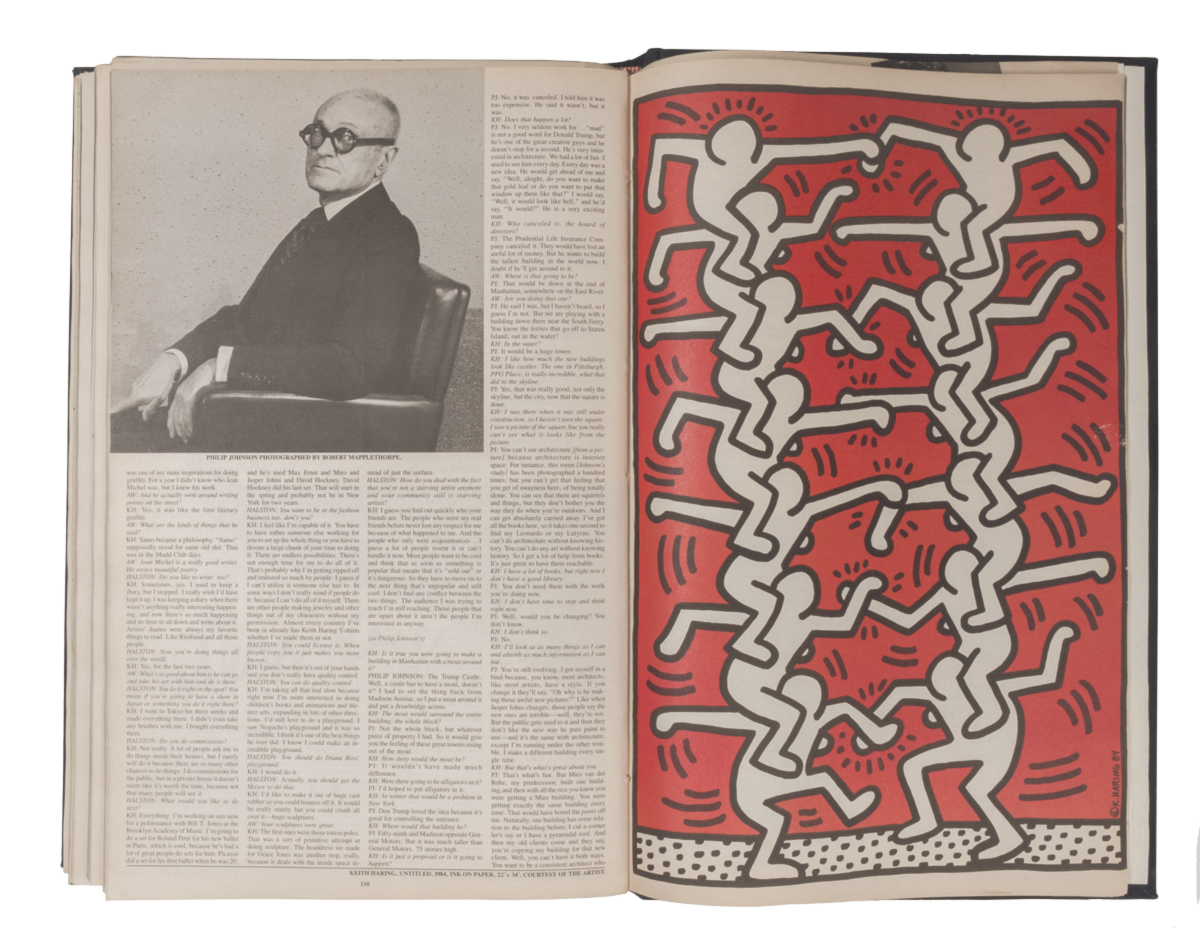

In the progression of artistic movements from Expressionism through Pop, the figurative work of Keith Haring stands out as an exceptional step forward. Incorporating the simplicity, frivolity and humor of Pop, Haring has gone further to invent an original vocabulary of symbols at once recognizable and evocative—the crawling baby, barking dog, portable pyramid, zapping spaceship—sometimes done on canvas, more often chalk—drawn on subway station ad boards, buildings, or sidewalks. Free of specific cultural references, the drawings speak with equal clarity to sophisticated viewers and mere passerby, in a deeply human voice.

Raised in Kutztown, Pennsylvania, Haring came to New York in the late ’70s and attended the School of Visual Arts. Soon discovering that “the most beautiful paintings in the city were being shown on wheels (by the graffitists),” Haring began his subway drawings as a lark, and became a celebrity underground and above, with his first gallery exhibition in 1981. In spite of the proliferation of international showings and press since then, including the recently published photographic study, Art in Transit (Harmony Books), the artist and his work have maintained their charming innocence.

This interview with designer Halston and Andy Warhol at a weekend house in Montauk offers a stereoscopic view into Haring’s special world.

———

HALSTON: When did you start drawing?

KEITH HARING: When I was four years old. Everybody draws when they are little.

ANDY WARHOL: I drew flies.

HALSTON: You drew flies?

WARHOL: Doesn’t everybody draw flies?

HALSTON: Do you work for TV?

HARING: I wish I had done something for these Olympics. It would have been great to have done a huge running man on top of the Coliseum or something.

HALSTON: You should do a comic strip, too. Did you ever do a comic strip?

HARING: No, not really. I’ve been drawing cartoons since I was little but…

HALSTON: Walt Disney could use a new character.

HARING: I’ve always wanted to work for Walt Disney. That’s what I thought I was going to do when I grew up.

WARHOL: The crawling baby could really be a good daily comic strip.

HARING: Except I think that would ruin it. I think when you turn things into serials like that, it ruins it.

HALSTON: What if you make a movie out of it?

HARING: When they put Snoopy and Peanuts on television, it just ruined it.

HALSTON: Well, then you could go into crawling teenagers and dolls and things. And then women and old people.

HARING: Speaking of old people, I did a thing for a medicine company in Germany to advertise a heart medicine.

HALSTON: A heart medicine? What kind?

HARING: It’s a new heart medicine, I forget what it’s called. It’s for cardiac arrest.

HALSTON: I like it just called “heart medicine.”

HARING: They used some of my drawings to promote their produce in medical journals and things. It’s funny, I get the weirdest offers.

HALSTON: What’s the weirdest offer you’ve ever had?

HARING: I had a call from a firm that represents the polyester industry. It had to do with a big media event to try to get polyester back on the map.

HALSTON: I never thought it left the map. You’ve done a book already?

HARING: I’ve published one book with Tony Shafrazi. It was sort of like a catalog, not really a book. I have a book coming out now that I did with Harmony Books of photographs by Tseng Kwong Chi of the subway drawings from the last three years with a foreword by Henry Geldzahler. Actually, I have a great picture of me with Mayor Koch, as I present him this book and he makes this really horrible face, like, “Who is this guy and how did he get in my office?”

HALSTON: I saw him on TV the other day saying that he hated graffiti. But you don’t consider yourself a graffiti artist.

HARING: Mayor Koch hates it a lot. What I call it doesn’t matter because the media calls it graffiti.

HALSTON: What would you prefer calling it?

HARING: I call it drawing. It was ironic that I got to meet the mayor because of that litter pig thing. The Sanitation Department has a new anti-litter campaign for the city called “Don’t Be a Litter Pig” and they asked me to design the pig for it. I had to do this press conference with him for the anti-litter campaign, so I took the opportunity to give him the book and sort of confront him with it. He had to accept it and shake my hand because I was there to do something free for the city.

HALSTON: It costs ten million dollars a year to remove graffiti, doesn’t it?

HARING: Yes, but it’s really a waste of money because they’re not going to wipe it out anyway. They can’t stop it. All they can do is chase the good artists off the trains.

WARHOL: What’s the difference?

HARING: The trains in 1978 and 1979 were incredible. That’s when an artist would spend eight hours on one car. No one does that anymore. Every now and then you see a piece, but now they have these huge buffing machines with a chemical wash that they run the trains through. No one will spend eight hours if they’re going to have their piece ruined in two days.

HALSTON: Where did you grow up?

HARING: I grew up in Pennsylvania in a small town. Real small, like one high school and one movie theater. Well, there was a state college there, that was the only good thing about it.

WARHOL: When I came to New York I had one dish, one spoon, one fork. It’s actually more fun to have one school, one post office.

HARING: It made everything simpler, except that everybody knew you and everybody knew everything you were doing. And for me that wasn’t good because I started my childhood being a really good little kid: churchgoer, straight-A student, Little League team. And then by the time I was 15 and wanted to be a hippie…

WARHOL: What made you want that?

HARING: I guess being a little bit progressive by myself and just reading Life magazine and seeing Woodstock and the Democratic convention in Chicago on TV, things like that. It got to the point where I wanted to smoke pot so bad I bought tea. When I was 13 or 14, I tried to smoke tea hoping that would do something. I had no idea where to get pot from. Soon after that I found out where to get pot. So I started to hang out with college students when I was about 15, and that’s how I got to experiment with other things. And then I started hitchhiking and getting out of the town when I was 17.

WARHOL: Where did you go, Philadelphia?

HARING: No, usually the New Jersey shore. And one summer I ran away and lived at the Jersey shore for the whole summer because my parents refused to let me go work there. So I just did it anyway.

HALSTON: What kind of work did you do?

HARING: I was a paperboy when I was little, so I was always saving money. From the time I was 12 years old, I was buying savings bonds. So years later I took a thousand-dollar savings bond, bought a half-pound of pot and moved to the shore. I spent all the money and had the best time of my life. It was really great because I learned a lot and grew up and learned how to live with people and live by myself.

HALSTON: Were you drawing all the time?

HARING: Yeah, I was, but I wasn’t taking it all that seriously.

HALSTON: When did you take it seriously?

HARING: I guess as soon as I started thinking of art and not cartoons, when I was 17 or 18.

HALSTON: What was the first thing you sold?

HARING: I sold little things when I was young.

HALSTON: How much money did you get for them?

HARING: The first thing I sold I got $135. That was when I was 17. It was a little ink drawing of a map of Berks County. When I was 17 I hitchhiked to New Jersey to go to this art exhibition on the Wildwood boardwalk. I took my little portfolio with me and was in this art show. It was the kind of show they have in shopping malls with all these really tacky crafts artists. But I got a prize and was real proud and sold a few little pen-and-ink drawings. I was hitchhiking to Beach Heaven in a car with this guy who said he was going almost all the way, and the portfolio was in the back seat. All of a sudden he changed his mind and was going a different way, so I had to get out really quick, and there was a line of traffic. I got out and left the whole portfolio of my work in the back seat. I never saw it again, and it was everything I had done up to that time. I just started all over and everything got better. Things like that happen to me a lot. I just want to go forward, forget about it and do something different. I just seemed like it kept getting better.

WARHOL: You did the baby on Union Square, didn’t you?

HARING: That wasn’t until 1981 or ’82. I didn’t start doing graffiti until two years after I got to New York. Jean Michel Basquiat was one of my main inspirations for doing graffiti. For a year I didn’t know who Jean Michel was, but I knew his work.

WARHOL: And he actually went around writing poems on the street?

HARING: Yes, it was like the first literary graffiti.

WARHOL: What are the kinds of things that he said?

HARING: Samo became a philosophy. “Samo” supposedly stood for same old shit. That was in the Mudd Club days.

WARHOL: Jean Michel is a really good writer. He writes beautiful poetry.

HALSTON: Do you like to write, too?

HARING: Sometimes, yes. I used to keep a diary, but I stopped. I really wish I’d have kept it up. I was keeping a diary when there wasn’t anything really interesting happening, and now there’s so much happening and no time to sit down and write about it. Artists’ diaries were my favorite thing to read, like Rimbaud and all those people.

HALSTON: Now you’re doing things all over the world.

HARING: Yes, for the last two years.

WARHOL: What’s so good about him is he can go and take his art with him and do it there.

HALSTON: You do it right on the spot? You mean if you’re going to have a show in Japan or something you do it right there?

HARING: I went to Tokyo for three weeks and made everything there. I didn’t even take any brushes with me. I bought everything there.

HALSTON: Do you do commissions?

HARING: Not really. A lot of people ask me to do things inside their houses, but I rarely will do it because there are so many other chances to do things. I do commissions for the public, but in a private house it doesn’t seem like it’s worth the time, because not that many people will see it.

HALSTON: What would you like to do next?

HARING: Everything. I’m working on sets now for a performance with Bill T. Jones at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. I’m going to do a set for Roland Petit for his new ballet in Paris, which is cool, because he’s had a lot of great people do sets for him. Picasso did a set for his first ballet when he was 20, and he’s used Max Ernst and Miro and Jasper Johns and David Hockney. David Hockney did his last set. That will start in the spring and probably not be in New York for two years.

HALSTON: You want to be in the fashion business too, don’t you?

HARING: I feel like I’m capable of it. You have to have either someone else working for you to set up the whole thing or you have to devote a large chunk of your time to doing it. There are endless possibilities. There’s not enough time for me to do all of it. That’s probably why I’m getting ripped off and imitated so much by people. I guess if I can’t utilize it someone else has to. In some ways I don’t really mind if people do it, because I can’t do all of it myself. There are other people making jewelry and other things out of my characters without my permission. Almost every country I’ve been in already has Keith Haring T-shirts whether I’ve made them or not.

HALSTON: You could license it. When people copy you, it just makes you more known.

HARING: I guess, but then it’s out of your hands and you don’t really have quality control.

HALSTON: You can do quality control.

HARING: I’m taking all that real slow because right now I’m more interested in doing children’s books and animations and theater sets, expanding in lots of other directions. I’d still love to do a playground. I saw Noguchi’s playground and it was so incredible. I think it’s one of the best things he ever did. I know I could make an incredible playground.

HALSTON: You should do Diana Ross’ playground.

HARING: I would do it.

HALSTON: Actually, you should get the Mayor to do that.

HARING: I’d like to make it out of huge cast rubber so you could bounce off it. It would be really sturdy, but you could climb all over it—huge sculptures.

WARHOL: Your sculptures were great.

HARING: The first ones were those totem poles. That was a sort of primitive attempt at doing sculpture. The headdress we made for Grace Jones was another step, really, because it deals with the inside space instead of just the surface.

HALSTON: How do you deal with the fact that you’re not a starving artist anymore and your community still is starving artists?

HARING: I guess you find out quickly who your friends are. The people who were my real friends before never lost any respect for me because of what happened to me. And the people who only were acquaintances… I guess a lot of people resent it or can’t handle it now. Most people want to be cool and think that as soon as something is popular that means that it’s “sold out” or it’s dangerous. So they have to move on to the next thing that’s unpopular and still cool. I don’t find any conflict between the two things. The audience I was trying to reach I’m still reaching. Those people that are upset about it aren’t the people I’m interested in anyway.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE DECEMBER 1984 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

———

Read more stories from the Celebrating Warhol collection.