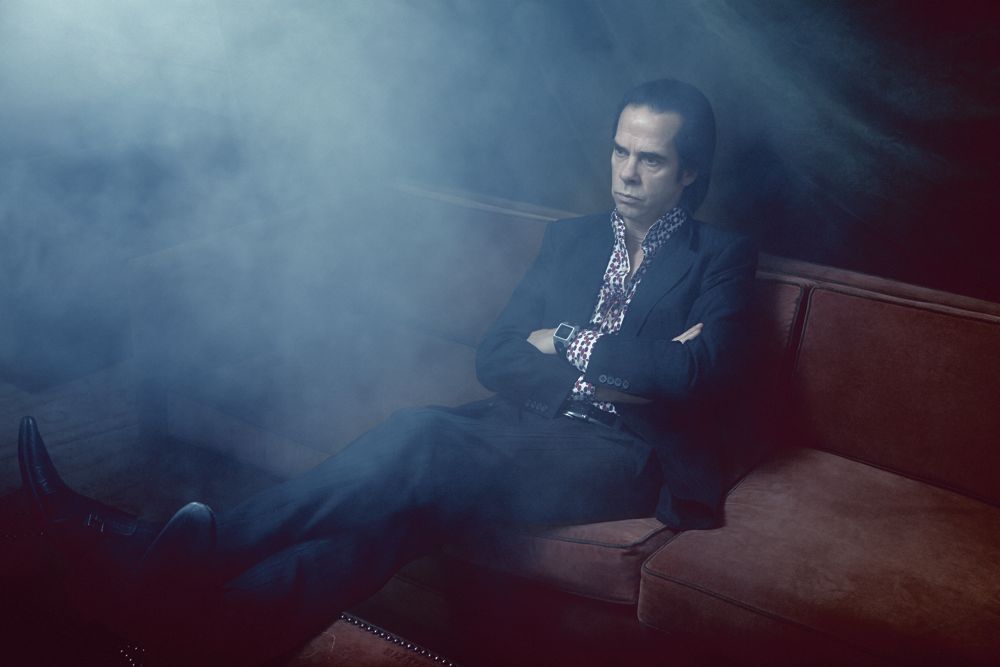

Nick Cave

I was waking up cold turkey and going to church, and then trotting down to the golden road and scoring and getting back home and shooting up and going, ‘I’m living a well-rounded existence.’ Nick Cave

Nick Cave’s mind is a deep spring of dark beauty and improbable inspirations. He is a restless creator, skipping blithely across genres and forms, from music and literature to screenwriting, acting, and even theater. After cutting his teeth in the late ’70s and early ’80s with the bombastic Australian goth-rock progenitors the Birthday Party, Cave assembled the seminal post-punk outfit the Bad Seeds in 1983, refining his music’s mix of blues, gospel, and experimental elements. He also fully came into his persona as a noir antihero with his elegiac baritone and a narrative songwriting style that has always suggested a deeper mythology. But the role of rock musician has never been enough to contain Cave’s overflow of creative energy. He published his first book, King Ink, in 1988 and since then has published four more (And the Ass Saw the Angel in 1989, The Complete Lyrics in 2001 and 2006, and The Death of Bunny Munro in 2009). He has written screenplays for the spectacularly gory Western The Proposition (2005) and the 1930s crime drama Lawless (2012); and, with his longtime collaborator Warren Ellis, he has composed numerous original films scores, including those for Andrew Dominik’s The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007) and John Hillcoat’s The Road (2009). He has even found himself in front of the camera on occasion, appearing in the 1989 Australian film Ghosts … of the Civil Dead and the 1991 indie classic Johnny Suede, and has worked with Ellis to score stage productions of Woyzeck, Metamorphosis, and Faust for the Vesturport and Reykjavík City Theatre companies in Iceland.

Following a five-year hiatus during which Cave explored garage-rock ferocity with his side band Grinderman, the Bad Seeds returned in February with their 15th studio album, Push the Sky Away (Bad Seed Ltd.), a quieter, more minimalist collection of songs than the group’s previous effort, 2008’s Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!!, but one that still manages to convey the Seeds’ brand of mystery and menace.

Cave, now 55, recently reunited with Jesse James director Dominik at the Sunset Marquis hotel bar in West Hollywood, where their conversation spanned the Cave oeuvre and even included a surprise guest appearance by the original Wild Rose herself, Kylie Minogue, who was in Los Angeles recording an album.

ANDREW DOMINIK: I’m curious about when you write a song about a particular person or an event in your life—like the song “Far From Me.” Do you think of that person or thing when you hear the song?

NICK CAVE: Yeah. And when I sing those songs at a gig, they bring me to that person, like they kind of regenerate the memory of that person over and over and over again—an imagined memory of that person. When I’m singing “Deanna,” for example, which I sing pretty much every night, it brings forward a kind of imagined, romanticized lie about this particular person, which I find really comforting and exciting to sing about. Sometimes the song isn’t strong enough to contain the fiction, because memories are fictions. And the songs kind of break down and are not singable, so they don’t ever get played live, because they’re not strong enough to contain the memory of that person. But “Deanna,” who you know, because she became your girlfriend and you have a child from her …

DOMINIK: Actually, when I started going out with Deanna [Bond] was when the song came out.

CAVE: Oh, really? I didn’t know that! [laughs]

DOMINIK: I don’t find your lyrics obtuse or difficult to understand in any way. I’ve been listening to you for 25 years. Those songs have always been a part of my life, so I have ideas about all of them—all the ones that have meant something to me. With “Deanna,” the one thing I always used to wonder about was the chorus: “I ain’t down here for your money / I ain’t down here for your love / … I’m down here for your soul.”

CAVE: For me, that particular chorus is beautiful in that song because in a live situation, it takes that song out of the personal and becomes something that I’m singing to everybody, and then it kind of telescopes back into this song about this mythic relationship that I had with your former girlfriend. [laughs]

DOMINIK: She told me you’d known her for, like, two weeks, and you’d gone to England and come back, and she went to the recording studio, and the first thing that she was presented with was you singing the song to her. And the song predicts the life that you’re going to lead together to some extent.

CAVE: Songs do do that, and that’s the uncanny and sometimes scary thing about a song. Susie [Bick], my wife, understands that very well. I wrote a song off the new record called “Wide Lovely Eyes,” which is about a woman going away and their sort of disassembling of a relationship. She’s like, “Why did you write that?” Not that she would ever ask me what a line is in a song, because she’s an artist at heart, and artists don’t ask other artists that because they understand that you just write what you can write. But the songs do kind of feel like they know something sometimes that I don’t know. Or even that they are more courageous, in the sense that your art can pave the way for what might follow. But “Wide Lovely Eyes” is really about the anxiety I feel when Susie goes away. It’s basically a song where I watch her out of the windows of my place do this walk that goes through the gardens in front of my house and down to the sea. And there is an anxiety that one day she won’t come back. Not that she’s going to leave me or something, but in the most abstract sense that’s what drives the melancholy of that particular song.

DOMINIK: Do you worry, then, if you come across a bit of grit in a song? A line might suggest that there’s a loose thread in your life?

CAVE: Well, I think our relationship is in much better shape if I’m writing songs like that than, you know, “How Sweet It Is to Be Loved by You.”

DOMINIK: I agree. There has to be room for all sides of a person, otherwise, if something’s repressed, it’s going to pop at some point.

CAVE: Going back to the “Deanna” song, even though it’s a wildly imagined universe—it’s a mythic kind of song, obviously—there’s much in it that is quite accurate in a weird sort of way about that short period of time I spent with her. Those songs do, in a live situation, if they’re any good, springboard me back into the past or encourage the ghosts of the past to come that little bit closer. And the older I get, the more I feel those kinds of ghosts—especially the women in my life—moving out of the shadows a bit more and becoming more present in my life.

DOMINIK: What do you mean?

CAVE: Those kind of memories—before it was kind of one after another and you found a new one. But the value of those relationships is much more important to me now than 10 years ago. Maybe it’s because I’m settled in a relationship. They feel like they’re coming out of the shadows. I’m only talking in the most abstract way. I have no interest in reconnecting on Facebook with these people or something like that. But those memories are becoming clearer to me.

DOMINIK: Movies are the same way. They have an unconscious thing going on inside them. The song comes into being in a certain period of time before it’s lost its mystery, before you know what it means to you. You can write a script and you’re following some impulse, but you’re not really aware of its meaning. But after you live with it for, like, three years, you start to see that the things that are predicted come true, or you start to see what it’s about, and it’s like the unconscious energy dissipates.

CAVE: Your movies seem to be about fiction and myth and what happened and what didn’t happen, or at least Chopper [2000] and The Assassination of Jesse James feel very much about that. I know you were meticulous, or as meticulous as you could be, with Jesse James, but that film seems to me to be very much imagined, mythic.

DOMINIK: Yeah, but there’s two people—one of them is very anxious and the other one’s depressed—and it’s really a sort of tale of suicide. It reminds me of events in my life, things that I’ve been around. It’s a fantasy, but still it has emotional energies, and they come from somewhere.

CAVE: Is it easier for you to do that in a period film? You were saying on the bus last night, when we were going to the gig [in San Diego], that they’re the books you’re most interested in—books that occur in another period of time. Is that because it’s easier to fictionalize and to imagine?

“The older I get, the more I feel those kinds of ghosts—especially the women in my life—moving out of the shadows.” nick cave

DOMINIK: I just think it’s more mythological somehow. There’s something more archetypal about it. They say that stories are how we give meaning to our lives; they’re how we organize reality. Fairy tales are descriptions of unconscious processes that a child has in order to deal with abandonment, and this is potentially the use of movies, of stories. And I think songs are the same. A song can offer advice on how to deal with a situation. It can be a conduit to grief—to being able to feel something.

CAVE: I think it can work in that way. But I would hate to think my songs were giving advice to people.

DOMINIK: It’s more in the sense of survival.

CAVE: Yeah. I often get people writing to me about how these songs helped them through a situation. But I would have thought the power of a good song is that it draws you out of your own situation and that you enter a completely different world. And that’s what I like about watching a movie: you enter an imagined world that’s more interesting, more engaging than your own. Or less painful than your own.

DOMINIK: The fantasy gives you the courage to feel things.

CAVE: Movies are wonderful like that. Where you find yourself weeping in the cinema, and it’s over a little thing. One of my triggers is a man trying to do the right thing. It gets me every time.

DOMINIK: Do you want to know how the subject of the song reacts to it?

CAVE: No. Early on I realized when you write a song about someone, it flatters them on some level, and gives you a lot of room to move within a relationship. A song can kind of get the girl, for sure. But for me and Susie, there is a kind of pact that goes on between the writer and subject, or the particular muse at the time. There is nothing private and there’s nothing sacred—there’s nothing that isn’t food for the songs.

DOMINIK: This is a conversation that you’ve had?

CAVE: I have talked to her about this: “You’ll get immortalized, you’ll be in songs. But you’ve got to understand that anything vaguely interesting that happens between us will end up mashed into some sort of song.” [laughs] But it doesn’t really matter what’s said about the person, ultimately. That someone sat down and spent that amount of time thinking about them, no matter how they’re thinking about them, is a compliment in some way.

DOMINIK: Like “Scum.”

CAVE: I was just thinking about “Scum.” Mat [Snow, the music journalist] loves that song.

DOMINIK: I’m sure he does. What do you think of “Scum?” Is it something that was tossed off?

CAVE: Musically, it was very much tossed off, because we didn’t want to spend any time doing the music to it—it would have defeated the purpose.

DOMINIK: It’s a favorite of mine, because it’s so vicious. The feeling in it is so palpable.

CAVE: The thing about that song is that what initiated it was the tiniest thing. I remember to this day that I’d opened up the paper … Snow had written a review of the first Bad Seeds record, From Her to Eternity [1984], calling it one of the greatest rock records ever made. Then we put out the next one, that bluesy one—

DOMINIK: The Firstborn Is Dead [1985].

CAVE: Which he said in a review of a single by [the German industrial band] Einstürzende Neubauten, something like, “Unlike the Bad Seeds’ latest record, which lacks dramatic intensity, this record, blah blah blah …” I just grabbed hold of those fucking three words like, “You fucker.” As I do, I stewed on that and sat down and wrote this bilious song about him, because I had lived with him.

DOMINIK: You weren’t living there at the time.

CAVE: No. But that kind of rage behind something like that is infectious and ultimately really enjoyable.

DOMINIK: It must be great to be able to vent things immediately. That’s the thing that I look at with such envy about music.

CAVE: Well, I’ve watched you make movies. I’ve watched John Hillcoat making movies, and I cannot understand how he can do what he does. Hang on to an idea and just push on and push on …

DOMINIK: Orson Welles said making a movie is like playing with the biggest train set any boy ever had. It involves every discipline: you write, you deal with performance, you deal with architecture, you deal with sound, you deal with music. And there’s a certain point in the making of a film when you feel like you’re in charge of an orchestra, and every little piece of it is building to something. What you really need more than anything is just the ability to endure frustration.

CAVE: Yeah … John has that ability.

DOMINIK: The other thing I wanted to ask about songwriting is about the relationship between words and music. I know that some people will come up with a riff, and then they have to get vowel sounds—”ar,” “eh”—the sound that will sound good with that music. They almost scat along before the words appear.

CAVE: That happens when we do songwriting together as a band, which we do with Grinderman. I ad lib initially, and that has just as much to do with what sounds good as with what something means. There is a great thing that goes on with that, because we do it for five or six days solid—playing from the morning till late at night without stopping. That does create a certain type of hysteria in the studio—lyrical hysteria, where you’re singing just to entertain the troops. You’re singing about stuff that, taken out of context, you can’t even believe is coming out of your mouth. And sometimes that stuff works really well with Grinderman, where it’s a kind of theme that you can develop.

DOMINIK: And then there are other songs that start with words?

CAVE: Yeah, they go in different ways. But it’s kind of a private thing—other than those Grinderman sessions where I’m dealing very much with the band members, I’m alone in an office somewhere writing songs with a pencil.

DOMINIK: And what’s it like when you have to present a song to the band?

CAVE: It used to be terrifying. There’s much more communication within the Bad Seeds now than there used to be. No one talked about music or ever said anything like, “That sounds good.” So you would say, “Right, this one goes like this,” and you start playing at the piano and singing, and then you finish and everyone just stands there, and they drift off and pick up the thing. So you never knew the effect that the songs had back then. Now, with Warren in the band, he talks about music all the time.

DOMINIK: At least they enjoyed playing it, right?

CAVE: Blixa [Bargeld, former Bad Seeds guitarist], usually after a record, would come up to me and go, “Darling, we’ve made a good record.” And then, “Goodbye.” That always meant a whole lot to me.

DOMINIK: Would he tell you if he didn’t like something?

CAVE: Oh, yeah. One time I wrote this song called “Sheep May Safely Graze,” which was about my child, and how I’ll protect him from the wolves and the crocodiles. It was, to be fair, a pretty sentimental kind of thing. Blixa came over and said, “Darling, let’s leave that one for the child.” [laughs] “Go home and play it to him. Let’s not inflict that on the world.”

DOMINIK: The new record seems less narrative.

CAVE: I’ve always hated narrative songs. I hate those songs where, basically, it’s an unfolding of a story. Dylan wrote like that. I can’t bear them, to be honest—you know, “The Ballad of Such and Such.” You listen to the story—and it’s beautifully written. But on some level, you hear it once and you’ve got the gist of it. There’s this kind of tyranny of the narrative, where you have to engage from the beginning of the song and listen to the end. But I’ve always found that that’s just the way I write. If I can’t visualize the thing on the page, it’s completely meaningless to me. I can’t write that “I love you, baby,” which are the songs I love, like a James Brown song, that just come and “get funky!” They’re the songs that I really respond to myself. But I’m a storyteller. I felt really pleased with this record and, to a certain extent, the last record, that the narrative structure had been shattered, but there are still highly visual songs where you enter a kind of world when you listen to them and things are going on, but you don’t have to get locked into them.

DOMINIK: I was thinking, watching the show last night, that that’s sort of similar to “Stranger Than Kindness.” It is an unusual song because it is like a collection of poetic non sequiturs that describe a relationship that you see in a dream fashion. That’s similar to the new record.

CAVE: I love that song because I didn’t write it, for one thing. Anita [Lane] wrote the lyrics, and I don’t fully understand it. I know it’s about me.

DOMINIK: You certainly get pictures—you get the essence of something. And therefore it’s larger.

CAVE: It all connects me very much to that memory of Anita. That’s what I was talking about before. That’s what all the songs to me are largely about: memory. That’s why when I hear that our record’s been bought, that we’ve lost our catalogs to some multinational company—EMI—and then they sold them to somewhere else, and there’s someone there that’s looking at the figures and seeing whether they should delete this record, you know, whether it’s worth it even being manufactured anymore … It is terrifying.

DOMINIK: Do you think there’s any danger of that?

CAVE: Oh, yeah, for sure.

DOMINIK: Well, Bella [Heathcote, Dominik’s partner] got up this morning and bought the entire Bad Seeds back catalog.

CAVE: Did she? [laughs] Very good. You know the great thing about the internet is that it’s gonna save that. Maybe nobody’s making any money on it—I don’t really care about that aspect—but at least you can listen to pretty much any song I’ve ever done, or anybody’s ever done. And those songs’ fate isn’t at the whim of some fucking bean counter at EMI.

DOMINIK: Why did you get into being a musician?

CAVE: I was talking to my kids, actually—they’re 12—I remember being that age and deciding I wanted to be a painter. I went to school and really got into painting and learned all about art history. It was the one subject that I excelled at because I had a genuine interest in it. I went to art school and then failed second year. I just thought I was the fucking greatest painter in the world. I was—we all were—heavily influenced by Brett Whiteley, the Australian painter, or Francis Bacon. We were makin’ Bacon, as they say. But I wasn’t actually painting very much in my second year. I was more meeting people and hanging out with the other artists. Being in art school was just amazing.

DOMINIK: Film school was the same.

CAVE: I’d gone from this stultifying grammar school and suddenly I was considered to be a fag and all the rest of it, and I was amongst these artists. It was amazing, but I failed. So my only option was this band; it had just been this thing we did on the weekends …

DOMINIK: Did you have any anxiety about getting up and singing? Did you have any shyness about it?

CAVE: I do have huge anxieties about it, not shyness. Maybe it’s shyness …

DOMINIK: You do now?

CAVE: I always do, yeah.

DOMINIK: But you didn’t feel that last night when you played your gig …

CAVE: No, I didn’t. You know, it’s just a thing about the voice. Last night was a good night for me—at least vocally. Some nights it’s not good. I was the singer because I was the unmusical one—I didn’t play anything amongst a group of friends at school. I had a certain way about being on stage, I guess. And then I could sort of scurry through the door of punk rock with my voice.

DOMINIK: When did you start to take it seriously?

CAVE: I don’t know how to answer that question, but I do know the moment when I realized we were on to something. We’d made the Birthday Party record [Prayers on Fire, 1981] with the song “King Ink.” I remember really clearly listening to the record with Rowland S. Howard after it had come out. It was like, “There’s something going on there. That’s not like other people’s songs.” There was something going on narratively and musically that was kind of gelling in that song that was different—that not only surpassed our influences but raised its head or broke free of the influences that are so apparent on that earlier Boys Next Door [Cave’s previous band] stuff.

DOMINIK: Rowland has said many times that it was fantastic to be in the Birthday Party, because he was in the best band in the world. They seemed like a thing that could explode at any moment. It kind of ended at the peak, right?

CAVE: Well, who knows where the peak was. But it ended very suddenly.

DOMINIK: Do you remember those times?

CAVE: I remember that there was a gig at a university or something like that, and this guy doing our publicity got all the record companies to come, and all these celebrities were there. It was a big showcase of the Birthday Party, and it was a night of absolute horror on every level. Tracy [Pew] had OD’d in the band room—we literally had to inject him with amphetamine to get him to wake up to get him on stage. Mick Harvey knocked me out on stage—there was some altercation with someone out front between me and the microphone stand and his head. And then Tracy kept falling over. And I think Rowland OD’d after the show. We got a big audience because of those sorts of gigs, I guess. [laughs] In a way, the Birthday Party set up something that we could react against for years to come. It was kind of a lovely force field that existed in people’s imaginations to propel the Bad Seeds’ career, where we could do different sorts of records. That kind of feeling of confusing or confounding the audience has always been one of those things that holds us together.

DOMINIK: Are you a contrary person by nature?

CAVE: There’s definitely a love of defending the indefensible. I’m sure you know that very well. [both laugh]

DOMINIK: Yeah. There’s a real joy that I feel in doing that, but much less as I get older.

CAVE: Exactly.

DOMINIK: Do you find life is easier with a project to organize it around? Have you gone through periods of doing nothing?

CAVE: Yeah. After the first time I went into a rehab, I came out and did nothing for, like, eight months—didn’t write a song, didn’t do any touring, just was supposed to be getting clean. And I just sat in this room on my own. I lived with Evan English—do you know him? He’s a producer …

DOMINIK: Yeah. That would’ve been awful. [laughs]

CAVE: I think I was watching seven videos a day.

DOMINIK: Would you not go to meetings and all that stuff?

CAVE: No, I didn’t get into that whole scene. People would come over and I would just sort of sit there with the remote like some mad person. They would try to talk and I would just turn up the volume.

DOMINIK: Did you not have the feeling of being restored when you got clean? Any sense of joy?

CAVE: No. I just thought, Okay, this is what life is; this is the fucking hell.

DOMINIK: You were just white-knuckling it.

CAVE: Then someone decided to do a tour of Brazil … [laughs] I just walked out into the sunshine there, grabbed a beer, and fell in love on the second day. And just never went home—stayed in Brazil. So that was not doing anything.

DOMINIK: That’s the last time?

CAVE: Well, no. There were other times where I couldn’t do anything because I was so fucked up. But since I stopped taking drugs 14 years ago, I’ve just worked, worked, worked. And progressively so. You may not remember saying this, but we were talking about scriptwriting, and you said, “What the fuck are you doing that for?” It had quite an impact. When I got asked to write The Proposition, it was this really exciting thing. I didn’t know anything about scriptwriting, so it was really exciting to just write the story I wanted to write. Then I did Lawless—and I had written a couple in between them, which were fun, too—and was suddenly like, “Oh, I’m a scriptwriter. This is what scriptwriters do; they get their notes and dash out something and send it back.” Around that time was when you said, “Why do you do this?”

DOMINIK: I guess I knew you took songwriting really seriously and that you took screenwriting less seriously, but if it’s fun—

CAVE: And I think you also said, “Maybe you should hack it out.” [laughs]

DOMINIK: Look, I figured it would be unpleasant for you to have to be taking notes, because you don’t have to. So why do it? I mean, if you can make music …

CAVE: Yeah. But the problem with making music is that no one wants you to make more than one record every three years. It’s different now because of the internet and the whole collapse of the record industry. But back in those days, it fucked up their marketing schedule if you made a record every two years, let alone one every year. It just wasn’t enough work, so that’s why I started doing extracurricular activities like writing books and that sort of stuff.

DOMINIK: The other thing I wanted to ask you is whether you believe in god.

CAVE: Well, I believe in the idea more than the actuality. I think it’s a part of us as human beings that we search outside of ourselves for meaning. It’s a hugely endearing aspect of our characters as human beings, despite how corrupt and destructive some of those ideas can be. But whether I actually believe in a god, in the traditional sense? I don’t. Religion is an act of the imagination, but on some level, it can be seen as a kind of failure of the imagination, because the idea is not that great. The idea is as small as our collective imagination can be, if you know what I mean. I’ve got to say that the first thing that disappeared for me when I got clean was my belief in god. I was fucking crazy. Towards the end, I was waking up cold turkey and going to church, sick as a fucking dog. I’m sitting there sweating and listening to everything, and then trotting down to the golden road and scoring and getting back home and shooting up and going, “I’m living a well-rounded existence.” [both laugh] You know, a bit of this and a bit of that. So the first thing that went was that supposed spiritual need of that conventional kind. But I don’t know why we went from nothing to something.

DOMINIK: What do you mean?

CAVE: The origins of the world and all that sort of stuff. I guess we know the how with the Big Bang, but what exists behind that gives me a certain kind of vertigo, even getting my head around that.

DOMINIK: So it’s the stories.

CAVE: Personally I find the story of Christ incredibly moving. And the way that the Gospels were written—despite the kind of hell those stories unleashed upon the world, even to this day, I find those stories very powerful and moving.

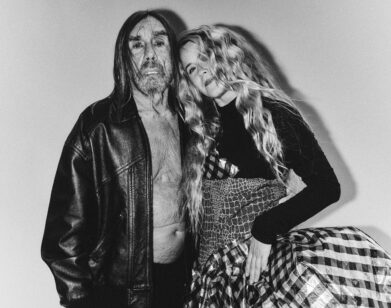

[Kylie Minogue and a rep from her management company enter the restaurant]

DOMINIK: Hey, some fancy ladies.

KYLIE MINOGUE: Hey, how are you?

DOMINIK: God, you look beautiful. How are you? I’m wearing these because I’m deaf and blind from seeing the Bad Seeds last night.

CAVE: We’re doing an interview.

MINOGUE: And I come in just at the end?

DOMINIK: Yeah, you can make a cameo appearance.

CAVE: Why are you here?

MINOGUE: I’m recording.

CAVE: Are you making a record here?

MINOGUE: I’ve actually got a listening session. I’ve got to go back to play it for the label.

CAVE: Oh, really? They haven’t heard it?

MINOGUE: It’s nearly done.

[Tape recorder pauses, then comes back with Minogue and Dominik talking]

MINOGUE: Okay. So while Nick is away, rustling up a menu, I can tell you that few men have really been very influential in my career, but he’s one of them.

CAVE: Are you on?

DOMINIK: We were talking about you.

CAVE: How influential?

MINOGUE: Super-influential. I don’t want to embarrass you.

CAVE: It doesn’t embarrass me.

MINOGUE: It’s only good things. [laughs]

DOMINIK: So do you remember when you became aware of Nick Cave?

MINOGUE: Yeah. When Michael Hutchence [the late lead singer of INXS] said to me, “My friend Nick wants to do a record with you.”

DOMINIK: I remember Mick Harvey had been ringing me to try to find your number for Michele [Bennett, a former girlfriend of Hutchence’s]. No, I think it was Mick rang me to get Michele to get Michael’s number.

MINOGUE: Wow, convoluted. So you spoke to Michael?

CAVE: I can’t remember. But anyway, Michael got spoken to [Minogue laughs], like, “Where’s Kylie? Because we want to ask her to sing.” And he goes, “She’s sitting right here.” You were at a hotel.

MINOGUE: Yes, maybe we were on holiday somewhere. Anyway, the message got passed, and then nothing happened for six years.

CAVE: Really?

MINOGUE: When did we do “Where the Wild Roses Grow”?

CAVE: I thought you came straight away and did it.

MINOGUE: No, because we did that in the mid-’90s, and I was dating Michael in, like, 1990, ’91.

CAVE: Are you sure about that? Because I thought we talked to you and said we got this song.

MINOGUE: Yeah, but that was years later in Melbourne, where it came through Mushroom Records. You were signed on Mushroom for a bit, right?

CAVE: Suicide Records, which was a subsidiary.

MINOGUE: Somehow we were on the same label, and I was asked about it, and a CD was sent over with your vocals and Blixa’s. And then I called you, but you were out, so I left a message with your mum. I said to her, “Well, he can call me at my mum’s house.” [laughs] And then the first day I met Nick was in the studio, which was cool because—

CAVE: We were all sitting there on our best behavior.

MINOGUE: You’ve always been on your best behavior when you’re with me. But it was great because it was like you were directing me.

CAVE: You sang it first take and there was a little bit of warbling on the end of the notes. Then we just asked you to not—

MINOGUE: To not sing it so much.

CAVE: To not sing it so well.

MINOGUE: Almost talking singing, and very fragile.

CAVE: And then you sang it.

MINOGUE: I don’t know how many takes, but it was really fast.

CAVE: Two takes.

MINOGUE: Was it? [laughs]

CAVE: Legend has it.

ANDREW DOMINIK IS AN AUSTRALIAN SCREENWRITER AND DIRECTOR.