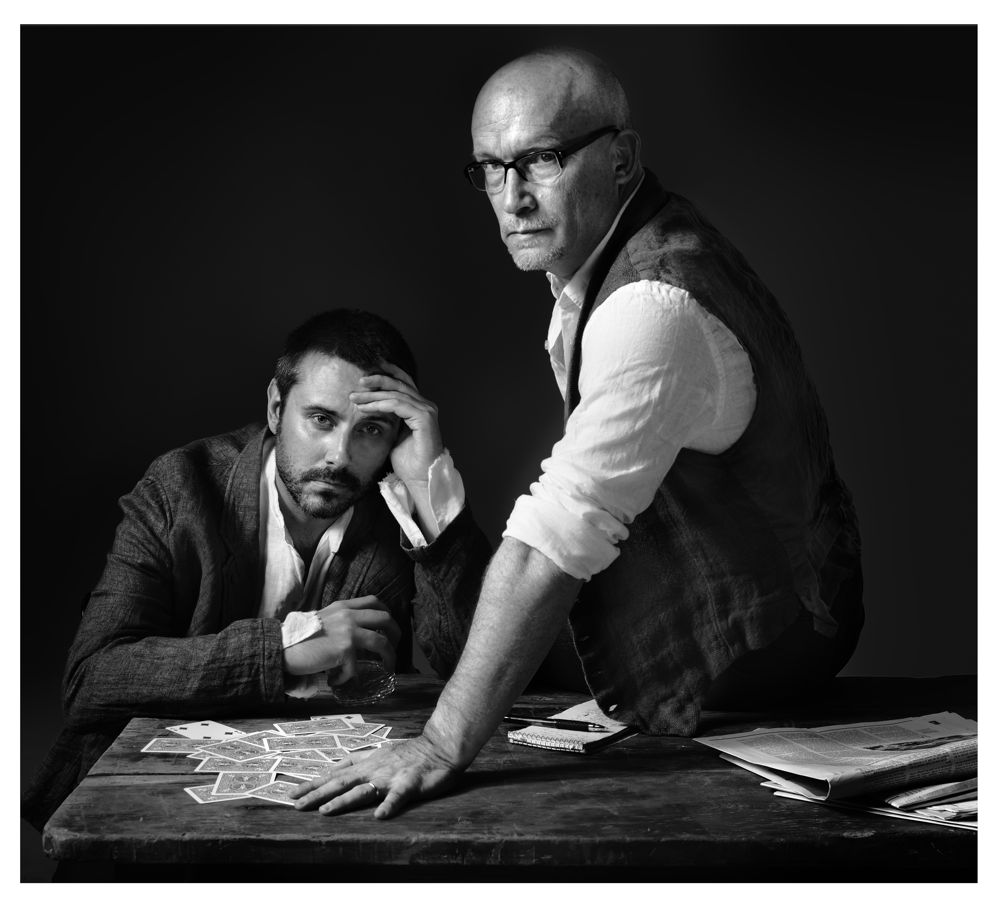

Jeremy Scahill & Alex Gibney

WikiLeaks was like a field day for those of us who are trying to be aggressive reporters …it was like piranhas picking at flesh. Jeremy Scahill

Transparency is tricky, mostly because of the numerous hypocritical landmines involved in advocating for it. After all, if you’re going to argue that everyone and everything should be transparent, then you yourself need to be a veritable open book in terms of both your mission and your methods, which is not always easily done and can occasionally reveal things to be not as they seem—in a bad way. But if you truly believe in transparency, then there are no more opaque ends that justify the means. You must reveal all—even with the knowledge that one of the oft-unintended consequences of total transparency is that the unadulterated truth can sometimes hurt or bring harm to the very people it is designed to serve. So it requires a commitment—to transparency—and a clear and unambiguous one.

Another aspect of transparency that makes it difficult is that, much like the chef’s tasting menu at some restaurants, it requires the total participation of the table—in order for it to work, everybody needs to be transparent. But in practice, that doesn’t happen very often. And so we live in a world where things are not entirely transparent, which is a subject at the crux of two new documentaries, Alex Gibney’s We Steal Secrets: The Story of WikiLeaks and Richard Rowley’s Dirty Wars. The films—in very different ways—explore the complications and the complexities of both secret-keeping and truth-seeking in an age when information might want to be free, but liberating the most important stuff continues to be a fight.

In We Steal Secrets, Gibney—director of the Oscar-nominated documentary Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (2005) and the Oscar-winning one Taxi to the Dark Side (2007)—turns his lens on the rise, fall, and impact of platinum-haired insurgent generalissimo and transparency evangelist Julian Assange and his renegade classified-information dissemination operation. While the film delves into the making of Assange (who declines to be interviewed for reasons revealed in the movie), it’s a story as much about whistleblowers and leakers as it is about self-styled revolutionaries and leaks-in particular, Bradley Manning, the American soldier who was arrested in 2010 after having passed to WikiLeaks a vast collection of classified combat videos, diplomatic cables, war logs, and other documents that is thought to be among the largest caches of restricted U.S. government material ever leaked.

Rowley’s Dirty Wars follows journalist Jeremy Scahill, a reporter for The Nation and author of the bestselling book Blackwater: The Rise of the World’s Most Powerful Mercenary Army, as he tries to gather information while covering a pair of apparently unrelated stories—one involving an air strike in Yemen and another about U.S.-backed warlords in Somalia. The investigations in both countries, though, lead him down a shadowy path toward an elite unit of the U.S. military known as JSOC, or the Joint Special Operations Command, what Scahill describes as a largely unacknowledged cross-divisional “all-star” team of forces—and one which receives a considerable bump in profile when, just as Rowley and Scahill are reporting on the stories depicted in Dirty Wars, JSOC becomes international news after it is publicly revealed to be the unit behind the killing of Osama bin Laden in Pakistan.

With We Steal Secrets and Dirty Wars in theaters and Manning’s trial set to begin this summer, Gibney and Scahill recently sat down in Brooklyn for a wide-ranging conversation about both films and what they discovered in making them, as well as the ethical, political, and human-emotional tightropes involved in both keeping secrets and revealing them.

ALEX GIBNEY: Your film is structured as a journey, but it didn’t start out the way it ended up.

JEREMY SCAHILL: We started out making a very different film. The director, Richard Rowley, and I had both been in and out of conflict zones for much of our adult lives, and we had worked together on various smaller projects, but wanted to do a bigger-picture film together. Rick had been embedded in Afghanistan, and both of us had been following the development of this sort of war within the war—the idea that you had these special operations troops conducting night raids, and journalists weren’t able to embed with them. So our film was originally going to be about Afghanistan, and we stumbled into a series of raids that had been conducted by Navy SEALs and Delta Force guys, and we soon realized that we were investigating this elite unit called JSOC—the Joint Special Operations Command. Our investigation eventually led us to Yemen and Somalia, and we were shooting over the course of two years. So we started to edit our film and showed a rough cut to some colleagues, including David Riker, who is a writer and director—he co-wrote Sleep Dealer [2008] and wrote and directed The City (La Ciudad) [1998] and The Girl with Abbie Cornish. David was going to come in and help us with the script, but after working with him for a year, we ended up with a completely different film. What David realized—and what we came to understand—is that our own story was hidden in plain sight. One of the themes of our film is that all the stuff we’re talking about, you can see—you just have to have the eyes to see it. So we made the decision to make it a more personal journey—which I had to be pulled kicking and screaming into doing because I like to tell other peoples’ stories, not my own. But in the end, what you see are some of the cold realities of what journalism actually looks like, and what it’s like to be investigating very powerful players, and how isolating that can be.

GIBNEY: I thought it was interesting not only as a narrative device, but in the way that it shows the power of asking simple questions and the role of the journalist in the Columbo-like search for what’s going on.

SCAHILL: There’s an interesting connection between your film and our film. There are two stories in our film. One is about these warlords in Somalia, and the other is about a cruise missile attack in Yemen. But while we were doing our film, the WikiLeaks cables came out, and we learned so much more about what had happened in both places than we ever would have known from just investigating it on the ground. I mean, these cables showed that General David Petraeus and other U.S. officials were conspiring with the Yemeni government to hide the fact that the United States was bombing Yemen. In fact, there’s a scene in our film where we’re trying to figure out where we’re going to go next in the investigation, and we’re going through the WikiLeaks cables. That was a tip of the hat to WikiLeaks because they fundamentally changed the way all of us see the world—those of us who are paying attention to these issues and working as journalists. I think the WikiLeaks story will go down as one of the most significant events in the history of the United States in terms of how it radically shifted the way the government is perceived by a large portion of the world’s population.

GIBNEY: It’s a peculiar thing because I think of it as something radically new and then also kind of old, in a way. I went into the story thinking two things: one, that it was a David-and-Goliath story about Julian Assange versus the world, or Julian Assange versus the American state; and two, that it was about a leaking machine. I agree with you in that I think that the cables and all of the documents and videos that WikiLeaks published—along with various news organizations—is fantastic. We mention in the film that it’s like a Wizard of Oz moment where you pull back the curtain. Of course, there was new technology involved, but that’s not the most important part of the story. The most interesting part, to me, was the story of a source and how that source winds up giving up information. Because everyone talks about Julian and WikiLeaks, but the person at the heart of the story, in many ways, is Bradley Manning. That was what we discovered. It was very lucky for us that Julian, ultimately, didn’t agree to be interviewed, because we ended up focusing far more on Manning than we might have otherwise, and he turned out to be an absolutely fascinating character. But also, you have to reckon with the fact that so much about that discovery process is about human beings talking to other human beings. The sad part was that Bradley really needed somebody to talk to. We know now that he invested far more in the relationship with Assange than Assange did. And when he didn’t have Assange anymore, then who did he turn to? Adrian Lamo [a hacker who was arrested in 2003 after having broken into the networks of The New York Times and Microsoft]—the guy who ultimately turns him in.

SCAHILL: Lamo was an informant for the government, right?

GIBNEY: It’s hard for me to know if he was at the time. But Lamo was a guy who, as Kevin Poulsen [a fellow hacker and an editor at Wired] says in the film, lived his life as if he were in a novel. So suddenly Lamo sees that he’s in the middle of a very important story and he wants to play a role. What kind of role? He’s not sure yet. You don’t know whether his motives are sincere or not, but he’s playing this strange double-agent role in a world of double agents with a guy who really just wants to connect to another human being.

SCAHILL: You mentioned that Wizard of Oz moment, and we had something similar happen with our film where we thought we were investigating one story, and we were pulling this string that was coming out of a hole in the wall, and we realized that behind the wall there was an elephant. We realized that we weren’t pulling a string at all, but an elephant’s tail—something attached to a behemoth. We were shooting our film in Yemen and Somalia, tracking the Joint Special Operations Command, and in the middle of filming, Osama bin Laden was killed—by the very unit we’d been tracking and chasing around the world.

GIBNEY: Now, when you say “unit,” you mean in the larger sense, JSOC?

SCAHILL: Yeah, the bin Laden raid was a JSOC-run operation. As you know, JSOC is like an all-star team of the military. It’s the Navy SEAL Team Six—which is also called DEVGRU—the Naval Special Warfare Development Group, there’s Delta Force, the 75th Rangers, and then the pilots are Night Stalkers, the 160th Aviation. So all of these forces together constitute JSOC. So bin Laden is killed by the Red Squadron of SEAL Team Six, and suddenly this group that we’ve been tracking becomes a household name. People start talking about JSOC on TV. The Disney corporation actually tries to trademark “SEAL Team Six.” Then Zero Dark Thirty very quickly goes into production. So I really did feel like our world sort of turned upside down. We talked about how to handle it within the film, and ultimately we just decided to keep reporting the story and see how it played out. But I remember watching the news the night bin Laden was killed and seeing Richard Engel [the NBC News correspondent] saying, “An organization that we’re going to be hearing a lot about is JSOC, the Joint Special Operations Command … ” I just melted on my couch. It was surreal, because we were just having doors slammed in our faces the whole time, and then all of the sudden, everyone’s talking about JSOC.

GIBNEY: It’s on TV.

SCAHILL: It’s all on TV, and they’re doing reenactments and showing the guys. And then you have these books coming out. One of the challenges we had was that we could not get any officials to sit down and talk about JSOC—especially before bin Laden was killed. No one wanted to go on record because, technically, it’s a group that, for the most part, doesn’t exist officially. But in your film, you have Michael Hayden, who is the former director of the CIA, and—

GIBNEY: Bill Leonard. He was the classification czar.

SCAHILL: Under Bush.

GIBNEY: Hayden was both CIA and NSA. He’d run both of them.

SCAHILL: You get both of those guys to talk in a really candid way. You can tell that you invested some time because they weren’t just giving you sound bites. How did you develop that level of rapport with them where they seemed so comfortable talking to you?

GIBNEY: Honestly, I don’t know. I’d never met Hayden before. My producer, Alexis Bloom, met him at a speech or a symposium, and said, “We’re doing this film, and we think it would be very important to chat with you because you know a lot about the subject.” Remarkably, he agreed. Also remarkably, he sat down with us for maybe two and a half hours, which is a lot of time to speak with people like us, coming in from the cold. We got into a lot of stuff. I was very interested in the el-Masri story [Khaled el-Masri, a German citizen, was mistakenly captured in 2003 by Macedonian authorities and handed over to the CIA, who then transferred him to a site in Afghanistan known as the “Salt Pit.” El-Masri was found to have been severely beaten and tortured while in detainment]. I was also interested in the whole Thomas Drake story [Drake, an official with the NSA turned whistleblower, was charged in 2010 under the Espionage Act of 1917 after revealing to a reporter information regarding waste, mismanagement, and potentially illegal activities at the agency]. But there’s something very compelling about Hayden. You know, I clearly don’t see eye-to-eye with him, but one of the film’s central ironies is that, at the end of the day, Mr. Transparency, Julian Assange, refused to sit down for an interview, but Michael Hayden did—and was as candid as he was willing to be with us. Bill Leonard, though, is also just a fascinating guy. He was a Reagan Republican, but then he ends up being the guy who wants to testify on behalf of Thomas Drake because he feels very strongly that something is deeply amiss in terms of how we treat our secrets. It’s interesting because you meet these guys in the heart of government and you realize that they are true believers in the best sense. They believe in the principles—and that the principles should be properly applied. So that was great because it gave the story some breadth and balance. Then P.J. Crowley, the State Department press officer, was another interesting guy. He played a dual role in the story because he comes to attack the administration for treating Bradley Manning so badly.

SCAHILL: He ultimately went down because he spoke out of school in a speech.

GIBNEY: Yeah, he spoke frankly—which was not appreciated. [laughs]

SCAHILL: You have that great moment in the film where P.J. Crowley has denounced the treatment of Bradley Manning in the custody of the military …

GIBNEY: Crowley was at a forum at M.I.T. and someone said, “Is that on the record?” And he said, “Yes, it’s on the record.”

SCAHILL: And then you cut to President Obama …

GIBNEY: At the press conference where a reporter says, “P.J. Crowley was quoted as saying that the treatment of Bradley Manning while he was in custody of the military was counterproductive and stupid. Would you care to comment?”

SCAHILL: You know, I cut my teeth in journalism in the ’90s, when Clinton was president. I covered the war in Yugoslavia, the Kosovo bombing, and spent a lot of time in Iraq …

GIBNEY: Who were you working for at the time?

SCAHILL: I was freelancing, but I started out in journalism as a coffee runner for Amy Goodman at Democracy Now!, and basically begged my way into an unpaid internship. At the time, she had just been kicked off every radio station in the state of Pennsylvania for airing the commentaries of Mumia Abu-Jamal. I remember I was working at a homeless shelter in D.C., just sort of mopping floors and taking people to appointments to try to get their benefits. A lot of the guys there were veterans. I’d started listening to a lot of radio, and I heard this woman talking about the revolution in the Congo against Mobutu Sese Seko, and they aired this interview with Laurent Kabila, who was in the mountains fighting. I hadn’t heard anything about this. It was in the papers, but it was like a revelation to me … I think of it as an Alice in Wonderland thing, where you sort of open the door and there’s this whole world on the other side. So I started writing Amy Goodman and calling her and showing up at speeches—I think she had to decide whether to get a restraining order or let me come in and volunteer. At first I worked on the technical side of radio, editing reel-to-reel tapes, but I was really interested in international stuff, and I ended up going to Iraq with a humanitarian delegation. Saddam Hussein was president and there were very few journalists there. This was in the lead-up to Clinton authorizing the bombing of Iraq in December 1998. But the first week I was in Iraq, I said, “This is what I want to do. I want to be a reporter and to tell stories of people whose stories would not be told if we don’t gather them.” It’s part of what I think of as the one-two punch of journalism. You’re trying to give voice to the voiceless, and then you’re also trying to hold those in power accountable, regardless of what party they’re in. But because I didn’t see it through the partisan lens that seems to dominate a lot of the perspective today with Fox News on the one side and MSNBC on the other, I didn’t see it as Democrats good, Republicans bad. I saw it as a situation where the United States is a force that engages in these military operations around the world, and it’s the job of journalists to provide the American people with information they can use to make informed decisions. I didn’t think of it as a matter of public policy that was tied to one party or the other. So when the Bush administration escalated the war in Iraq—because there was already a war going on there at the time—and then invaded the country and occupied it, I saw it as all part of the same trajectory. It was a bipartisan initiative. Now, here we are, and we have Obama in office, and he has drawn down forces in Iraq—which is a plan that was on Bush’s desk the day that he left office. The forces in Afghanistan, he’s going to draw down, too. But at the same time, Obama has also expanded a lot of the more unsavory, covert aspects of the wars, with the drone strikes and some of the night-raid missions …

GIBNEY: Well, it’s a classic example of noble-cause corruption. You realize what the framers had in mind. You see the natural progression of what happens when the executive gets power and then a new executive comes in. The new executive doesn’t say, “Oh, man. The president has just got too much power. We’re going to dial that back.” No, they expand the power. It’s like, “He didn’t use it well, so I’m going to take more power and use it better because I’m a better guy and my values are better.” Then you suddenly realize that the very people who were attacking Guantánamo prior to getting into office are now the people expanding an assassination program overseas …

SCAHILL: Dick Cheney will occasionally give a speech and talk about how Obama is weak on terrorism—forgetting that 9/11 happened on the Bush administration’s watch. Privately, though, I think these guys think, “Man, Obama is a gangster. He is so much better at what we wanted to do than we were.” Because he basically sold it to liberals!

GIBNEY: Hayden told me himself. I mentioned that they were expanding the drone program and he said, “Yeah, about that …”

SCAHILL: I quote Hayden in my book saying, “We were supposed to have a warrant to wiretap American citizens, but Obama doesn’t even need a warrant—or an indictment—to kill an American citizen,” which is what happened with three American citizens in Yemen in 2011.

GIBNEY: I think there’s a sort of grudging admiration for the lawlessness. But it’s interesting because you see the momentum of power take place. You see it on the ground in your film. The al-Awlaki case is a great one because it presents all of the conundrums of terror, but also the rule of law and how the state responds. [Anwar al-Awlaki, an American cleric living in Yemen alleged to have had affiliations with Al Qaeda, was reported to have been placed on a U.S. government “kill or capture list” and was ultimately killed in a drone strike in Yemen in 2011; his 16-year-old son was mistakenly killed in another drone strike two weeks later. Both were U.S. citizens.] You know much more about the al-Awlaki case than I do, but we don’t know precisely whether he was ever—

SCAHILL: Operational. We know that he was calling for armed attacks against the United States. He was praising the killing of U.S. troops, as in the Fort Hood shooting. But to me, the killing of Anwar al-Awlaki, al-Awlaki’s 16-year-old son, and Samir Khan [the American of Pakistani heritage who edited Inspire, an online English-language magazine reported to be published by Al Qaeda, and who was inadvertently killed in the same drone strike that killed al-Awlaki] raises a number of issues that are the furthest things from the minds or the speeches of Democratic or Republican politicians. It’s only, quite frankly, crazy people like Rand Paul who have made this a serious issue. Rand Paul is a bucket full of crazy on so much, but he was right on this particular issue. He had this filibuster, and there were a lot of crazy things said that day, but Rand Paul made some points that the American people need to face: that if we define our legal system and sense of justice as a society by how we treat the least of our people, then we’re doing something right. For example, if you want to oppose the death penalty and say that you’re against executions in the United States, then you need to be able to argue that a vile child murderer should not get the death penalty because that’s what the principle is—if you’re actually against the death penalty. In the case of al-Awlaki, even if he said all of these terrible things, then we have a system of laws and an opportunity to present evidence. It’s not that al-Awlaki was some heroic figure or that he was even necessarily innocent. It’s more about how we judge rule of law.

GIBNEY: One of the things that I think unites We Steal Secrets and Dirty Wars is this whole idea of “the end justifies the means”—this sense that so long as you have a noble end in mind, then it doesn’t matter what you do because you’re somehow inherently noble. In our film, you see this odd confluence. As much as it looks at how terrific WikiLeaks was—or really, the idea of this publishing mechanism that’s outside of national borders and somehow can take stuff that really should be kept secret and put it out there so we can all decide how we feel about it—at some point, Julian goes astray. Assange’s nickname is Mendax—short for splendide mendax, or “noble liar”—and at some point he decides that because what he’s doing is so good and so important, then it’s okay if he starts to shave the truth or behave a bit reprehensibly. After all, he’s doing something noble, which is not that different from what Michael Hayden describes when he says, “We steal secrets. That’s what we do.” But once you understand that, then when is it okay for us to steal secrets? And then when is it okay for us to put someone like Bradley Manning in jail for the rest of his life because he leaked secrets?

SCAHILL: You have this series of clips where you see prominent commentators and politicians calling for Assange to be

killed—by a drone.

GIBNEY: By a drone! Two or three people say that.

SCAHILL: There’s Bill O’Reilly and Fox News and some other people who all call for him to be killed by a drone. I was trying to put myself in Assange’s shoes. I mean, you have these commentators on perhaps the most powerful news network in the U.S. saying that you should be either snatched and put into Guantánamo or killed by a drone. There’s a sort of bravado that comes across in your film, but if you’re Assange and you’re watching this, then I’d think you’d be terrified—no matter how you viewed yourself.

GIBNEY: If you’re a human being, you’d have to be terrified. Also, the impunity … That these guys can sit on a TV show and just chat in a relaxed way about killing people. They’re joking, but at the same time, it’s a vicious kind of rhetoric. The degree of enmity and the show of power and force against Assange must have terrified him. He was prepared to be paranoid when he was young—when nobody was actually after him. But this easy kind of vitriol and hatred that you now see as part of common discourse, it’s become part and parcel of our everyday chatter. “Fuck ’em. We’re gonna kill that motherfucker.” Later on, Assange’s supporters are all over the internet putting bull’s-eyes over the faces of these Swedish women [who brought allegations of rape and sexual assault against Assange], as if to say, “Kill them.” It’s metaphorical, but it’s dark. That’s the flip side of the internet: it represents tremendous freedom, but when see that freedom is taken to a different place, it can be dark indeed.

SCAHILL: I was really happy to see you spend so much time in your film on the story of Bradley Manning. There was a lot of misreporting on Manning’s case—or a lack of reporting. I mean, The New York Times didn’t send a reporter to cover the Manning trial until people started protesting and saying, “You used the material that he provided—and used it to sell newspapers and to be ahead of the curve and pushed that agenda. And then when he goes down, you don’t even send a reporter to cover his prosecution?” I mean, it was stunning. From all we know about Bradley Manning and from the audio that was leaked from his court-martial hearing, where you hear him in his own words, it seems like he was truly a guy who had a conscience and was saying, “I don’t want to be a part of these things, and I want the world to know this.” And to come forward and own it the way he did in that hearing is very interesting. But for The New York Times to not even cover it was astonishing. And the way that they handled WikiLeaks in general … They just turned their back on the whole operation.

GIBNEY: There were very dismissive of WikiLeaks.

SCAHILL: Not just dismissive—they attacked.

GIBNEY: They personally attacked Assange in ways that I think were reprehensible. I think they did it because they were threatened in some fundamental way—that they thought, “Oh, my god, this is a new model that’s taking us on.” They’ll all deny that, but I think there was some threat in what WikiLeaks represented. But you had an actual connection to Bradley Manning, didn’t you?

SCAHILL: Well, I didn’t know Bradley Manning at all and had never, to my knowledge, been in touch with him, but I got an e-mail one day from a guy who was researching Manning’s life and, I think, writing a book. The guy said, “I heard through the grapevine that you had been in e-mail contact with Bradley Manning.” So I wrote back and said, “You heard wrong.” But he goes, “No, no. I’m pretty sure that my source is right on this,” and tells me to search my inbox for this particular e-mail address. So I searched my inbox, and sure enough, there’s an e-mail from Bradley Manning. Without revealing too much about it, he had given me a tip that he did not obtain through any classified information—it was through a personal connection—which facilitated me discovering that the head of Blackwater, Erik Prince, was preparing to flee the United States and relocate to the United Arab Emirates at a time when there were all these investigations into his company. It was because of Bradley Manning that I discovered this. So I broke that story, and I think a week or two later, The New York Times did a follow-up and confirmed that the story was in fact true. But it’s astonishing because I didn’t remember it at all. It’s also a lesson in journalism. I mean, there are so many e-mails that we get and never respond to.

GIBNEY: Well, it has now been revealed that Bradley Manning did go to The New York Times and The Washington Post, and there was a lot of ooga-booga about, “Oh, they dropped the ball.” But honestly, you probably get this more than I do, but I get a lot of people who e-mail me saying, “Look, man, I was there on the grassy knoll. I can tell you who the five shooters were.”

SCAHILL: Today I got an e-mail from someone who is insisting that the government must’ve known something about the terrorist incident at the Boston Marathon and that the creator of Family Guy was somehow involved in the plot. The e-mail goes on for four paragraphs, and there are multiple documents attached—like screen grabs and things. So then in sneaks this e-mail from a kid named Bradley Manning …

GIBNEY: “Hey. I’d really like to talk to you because I may have thousands of U.S. documents you might be interested in.”

SCAHILL: Right. Sure, you do … Why don’t we meet at Area 51 and you can give me the documents there? [both laugh]

GIBNEY: So you can understand why it wouldn’t have happened for him. But I think there was a moment when the renegade publisher, Julian Assange, met the traditional journalist that could have been incredible, because the traditional journalists gave him political cover, and if they both had learned a little bit more from each other, then it really could have been a game-changer. It would have been much harder for the U.S. government to go after Assange if he had been a little bit more careful, a little bit less doctrinaire, and if they, frankly, had been a little bit more protective of him. They should have seen, “Look, we’re grown-ups here, and this kid hasn’t been around the block.” But everybody got too fractious. It got too messy and personal. And it didn’t work—it blew apart—which was too bad.

SCAHILL: I think we’re in this era now where the people on Twitter are way ahead of the curve, and often beat the major networks to the story. There’s also a heck of a lot of misinformation that’s put out on Twitter, so it’s definitely a two-edged sword. But what’s fascinating is that it’s also this sort of effective fact-checking operation where the barons of the media industry have been taken down a few notches in their position in society because you have this collective of hundreds of millions of people around the world who are in some form or another engaging in something vaguely resembling journalism, or at least, engaged in a very public discourse where there are high stakes at times. WikiLeaks came at a moment where you had a strong tradition of citizen journalism and bloggers that had already been around for a while. But one way people at powerful newspapers butter their bread is through leaks. It’s always been that way. Part of it is because of their social circle. They hang out with the powerful, their kids go to fancy schools together, they see each other on weekends. But WikiLeaks was like a field day for those of us who are trying to be aggressive reporters. All of the sudden, the information was liberated, and it was like piranhas picking at flesh. I remember spending 72 hours digging into the cables and looking for specific things related to stories that I had done. I read every single Blackwater cable. But the powerful, elite journalists really took a blow when WikiLeaks came along, because the emperor suddenly seemed to have no clothes. It just sort of demystified the world of elite journalists, and I think that was a humbling experience for a lot of them. I think they did feel threatened.

GIBNEY: It’s also a bit like the collision of the Apple closed system and the Microsoft open system.

SCAHILL: Are you a Mac guy or a PC guy?

GIBNEY: I’m a Mac guy, but I appreciated the benefits and the deficits of each system. Establishment journalism, though, was a closed system: “We know it all, we’ll figure it out, we’ll hand it to you.” And while WikiLeaks showed a new way, it also showed the value in the old way. There’s a reason why you were careful to protect sources. There’s a reason why one person digging at a story for a long time can contextualize it and present it to people in a way that they can understand. Storytelling turns out to be important. Providing access to data, which is what WikiLeaks did, was tremendously valuable because then everybody could go in and search it. But making people understand why a cable is important is valuable, too.

SCAHILL: Marcy Wheeler, who I think is really a phenomenal blogger and journalist—she did the Firedoglake blog. She doesn’t have access to any sensitive sources. She does all open-source stuff.

GIBNEY: That’s what I.F. Stone [the independent American investigative journalist and author] used to do.

SCAHILL: But when you put someone like her in front of a mountain of cables, and you have someone who was built for journalism gaining access to the kind of information that used to just belong to very powerful journalists at major news outlets, it sort of leveled the playing field.

GIBNEY: The media now has become a more complete ecosystem. There’s clearly a value in The New York Times and The New Yorker and other outlets that do these great investigative pieces, and finding leaks in powerful places is terribly important. But if it’s not balanced with all this other stuff, then you inevitably take on the coloration of those people from whom you’re getting the leaks. That’s where WikiLeaks did explode the system. It proved that there’s more out there. The problem is that it’s not one way or the other. Julian is always on his high horse, saying, “Look at what WikiLeaks does. We’re good, and these other guys suck.” No! It’s all part of a larger ecosystem of information, which is also more demanding on us because it’s trickier to sift through. As you mentioned, there are a lot of lies on the internet, too. The first thing I thought about WikiLeaks was that it was going to become a new vehicle for the CIA. I thought the CIA would be leaking documents to WikiLeaks—like sites and pretending that they’re real when they’re not.

SCAHILL: That has happened. There were whole divisions of the U.S. intelligence apparatus that were, for decades, engaged in disinformation campaigns. I’m sure what you just described is already happening to some extent. I think it would be devastating, though, if we lost many of the components of old-school journalism—fact-checking, peer review, editing, copyediting. A lot of stuff is just slapped up online, and it’s open and it’s free. But there’s a reason why all those old institutions developed those programs. There’s a reason why at The Nation, where I work, every single thing that you write needs to be fact-checked. Sometimes it has to be reviewed by lawyers. So if we could combine the sort of new energy of this younger generation of social-media journalists with old-school muckraking and fact-checking and editing, then I think we’re looking at a new model of journalism.

GIBNEY: Another thing that I think unites these two films is the question of what happens when the state becomes more lawless. You see it in your film, particularly with the drone strikes as we begin to kill our own citizens without seemingly any real rhyme or reason. Bill Leonard was pointing out how we over-classify—which, by the way, is supposed to be prosecuted as vigorously as leaking. If you over-classify something in a way that’s designed to keep information away from the American public unnecessarily, you’re supposed to pay a price for that. But nobody ever pays that price. I remember when we went to Guantánamo, we pointed our camera at a mountain and we were starting to shoot it, and this woman who was from Lockheed Martin—I was like, “Why is this woman from Lockheed telling our lieutenant what to do?”—she said, “Sorry, that mountain is classified.” I said, “What do you mean the mountain is classified? I can google it when I get back to the other side of the bay.” She said, “Sorry, it’s classified. You may not shoot the mountain.” So in a world where we’re classifying a mountain, there’s going to be as sense of impunity about leaking stuff.

SCAHILL: Well, we lived in a world for several years under President Obama where everyone knew that drone strikes were happening regularly in Pakistan, increasingly in Yemen, occasionally in Somalia, and no official of the U.S. government would ever use the word drone or UAV or drone strike. They would never own it. Then who is the first U.S. official to publicly own it? It’s President Obama himself. How does he do it? On a Google chat. On a Google+ “Hangout.” [laughs] That’s the declassification of the drone program!

GIBNEY: I was at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner when he made that drone-strike joke, which got a big laugh.

SCAHILL: I remember how offended so many people were in a variety of countries because one of the few times that the United States acknowledges drone strikes is to make fun of it. I mean, we’re talking here just a few days after this incident happened in Boston at the marathon, and I’ve gotten e-mails from friends in Pakistan and Yemen expressing sympathy, but also saying, “Why aren’t we reported on in the same way when these things happen to us?” And I think it’s a fair question for people around the world to ask. You look at what happened after Virginia Tech or Newtown or now with Boston—we know the names of the people who were injured or whose lives were taken away. We know their stories. And it can be journalism at its best and its worst when these things happen. At its best, its humanizing people that we’ve lost in our society for no good reason—for an utterly atrocious thing that someone else has done. That’s what we should be doing as journalists. We should be telling those stories because it’s a way of saying, “We all have to own this.” If we covered these incidents in other countries with the same sensitivity about who the people are, then it’s not just, “A drone strike killed 16 suspected militants”—you’ll know the names of them, you’ll know something about their lives. And that changes hearts and minds. But we don’t have that. That’s what we tried to do in our film, to say, “Let’s put some human faces on a family in Afghanistan who had everything taken away from them and make them real.”

GIBNEY: Bill Leonard talks about that in a very poignant way. Here’s the classification czar for Bush saying, “Look, we’re a democracy. It’s important that we see these images of war.” To see something like the “Collateral Murder” video, where you see those Reuters employees and kids being killed or horribly wounded—you see the destruction being brought down on these individuals by these incredibly high-tech machines that are raining hell from above the clouds. But it’s important that we know that, that we see what war is. It’s always in the interest of governments to never let you see that stuff.

SCAHILL: Then you showed in the film that all of these other incidents are on YouTube, openly, where you can watch the best hits of the Apaches. Soldiers upload that stuff.

GIBNEY: So it’s secret, but it’s not secret; and then it’s classified, but it’s not classified—according the whim. Then you get to the point where you realize it’s about something that Nick Davies [investigative journalist for The Guardian] says in the film: that the over-classification of things is not about harm to American security, but about keeping the United States from being embarrassed. Of course, that’s what we’re supposed to do—we’re supposed to embarrass our government.

SCAHILL: I was thinking about the Apache video, and I’ve seen quite a few videos like that. I’ve looked at quite a few videos that Blackwater guys have posted online in their little circles where you see them shooting or engaged in some kind of grotesque behavior. I’ve even gotten e-mails from the wives or girlfriends of guys who were in Blackwater or other private companies like that who’d been screwed over or cheated on by these guys and offered to sell me the photographs off their computers. I’d never pay for any of them. I just don’t do that—as a journalist, I won’t pay someone for information. But I don’t even think we know a tiny fraction of the crimes that were committed in Iraq in our names. I don’t even think we have a tiny portion of the picture. It’s miniscule, what we know went on there. Not just the killing, but actual murder—because there’s a difference between killing and people intentionally murdering for sport and shooting other people for target practice and doing sadistic, twisted things. We hear stories. But I guarantee there’s video. There’s probably far more shocking video than anything we’ve ever seen. It’s just a matter of, are we ever going to see it?

GIBNEY: What’s the quote?

SCAHILL: It’s in your film.

GIBNEY: “Sunshine is the best disinfectant.”

SCAHILL: Right.

GIBNEY: You know that in war it’s inevitable that at some point people cross the line. We’re asking people to behave in a brutal fashion in a way that’s supposed to be disciplined, and at some point, it no longer is. And the only way to curb that behavior is to shine a light on it—because if you don’t, then the next step is barbarism. We’re beginning to see that under the excuse of guarding us against terror in all its forms, we’re committing horrible crimes, because it’s so important that we are protected. But when we cross that line, who are we? That’s the question.