IN CONVERSATION

How Far Will Michael Stulhbarg Go? Luca Guadagnino Wants to Find Out.

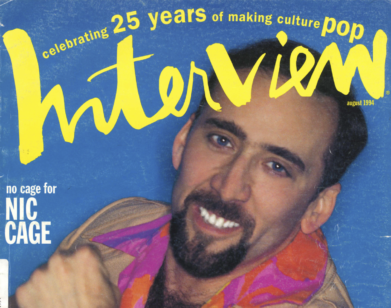

Michael Stuhlbarg, photographed by Emilio Madrid.

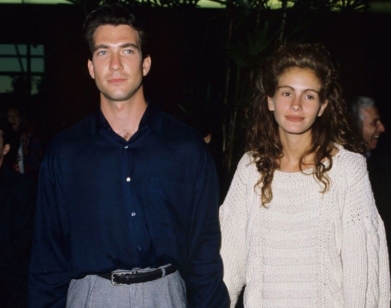

Michael Stuhlbarg and Luca Guadagnino are cinematic common-law partners by now, but their fourth film together might be their most searching yet. Winner of the Audience Award at this year’s Venice Film Festival this year, After the Hunt follows a revered professor whose convictions are tested when a former student resurfaces with a startling accusation. Acting alongside Julia Roberts, Andrew Garfield, and Ayo Edebiri, Stuhlbarg trades the paternal warmth of Call Me by Your Name for something more fractured, playing a man undone by his own contradictions. Unfolding at a prestigious New England college, Guadagnino’s 10th feature is a psychological thriller wrapped inside a melodrama, a tone he and Stuhlbarg have come to perfect. But how did they do it? After a grueling international press tour, the duo hopped on a Zoom call to tell all.

———

LUCA GUADAGNINO: Michael.

MICHAEL STUHLBARG: Luca.

GUADAGNINO: How are you?

STUHLBARG: I’m very well. And you?

GUADAGNINO: We’re in London, at the end of a long tour. We’re actually going to Paris tomorrow.

STUHLBARG: Hooray. You excited?

GUADAGNINO: I’m very excited, but I’m also excited to be back home soon.

STUHLBARG: Yes. My goodness. What a trip, eh?

GUADAGNINO: A long trip, but a great journey.

STUHLBARG: Indeed.

GUADAGNINO: And a great journey with you. Another one.

STUHLBARG: You as well.

GUADAGNINO: My first question to you is something I think about a lot: “When did I decide that I want to be what I am?” When did you decide that you want to be an actor? Did you decide or you just became it?

STUHLBARG: No, I never in a million years thought I would do it. My mom didn’t know what to do with my sister and I one summer when I was around 11 years old, so she put us in a community theater thing for kids.

GUADAGNINO: In New York?

STUHLBARG: No, this was in Long Beach, California.

GUADAGNINO: Because you are Californian.

STUHLBARG: I am. Born and raised.

GUADAGNINO: It’s crazy because you make me think a lot that you’re a New Yorker, but you’re not. You are Californian.

STUHLBARG: I’ve been in New York for almost three times as long as I was in California, but I’m very much a California kid at heart. So she threw us into this community theater and all I wanted to do was build the sets. I thought if I was going to be anything, it would be a painter or a cartoonist or maybe paint Disney cels, because that’s what came naturally to me. I was the kind of kid who enjoyed being alone making things. And everyone had to audition.

GUADAGNINO: Do you remember what you auditioned with? Which kind of text?

STUHLBARG: They just wanted to hear you sing because it was a musical. So I sang a song and they threw me in the chorus. I was bored one day during the middle of rehearsals and they said, “Well, the director said if you’re bored and want to do more, do something in rehearsals. Make yourself seen.” So I brought a bottle on and pretended to be drunk behind the leading lady, and she never turned around. She was facing out the entire way.

GUADAGNINO: Were you a little bit of a buffoon when you were a child?

STUHLBARG: I was. My initial inspiration was always making my family laugh, and I think it just became an extension of that. Cheering people up. If too much attention was paid in one direction, I put it in the other. I always felt like I was a balancer.

GUADAGNINO: Was it about them or about you?

STUHLBARG: Maybe it was just about the energy in the room, if that makes sense. It was about something being neglected.

GUADAGNINO: When you did the scene in After the Hunt at the beginning of the party, did you think about that?

STUHLBARG: No, not at all.

GUADAGNINO: Because Frederick does the same thing. He tries to direct the energy where he wants, the way you were back then.

STUHLBARG: Isn’t that funny? Yeah.

GUADAGNINO: And after you were this scamp, I guess you grew more willfully into becoming an actor. What did your parents make of that?

STUHLBARG: I think they were concerned until high school, around the age of 17, and then they started to say, “Well, let’s see where this goes.” I always was a very lucky kid in that they were supportive of everything and they never pressured me to do anything in regards to a career. It was what I was passionate about, and I couldn’t really think about anything else. So they let me run with it for a while, and then positive things started to happen.

GUADAGNINO: Like being accepted to Juilliard.

STUHLBARG: That’s right. That was pretty much the biggest step. I was an undergrad at UCLA for two years and all I could think about there was doing plays, and my grades started to suffer. A friend of mine was auditioning for Juilliard, and I auditioned with him and I got in, so I left.

GUADAGNINO: That’s interesting. I’m Italian, but Juilliard has always seemed like this world of heaven for actors and training. Did it eventually become a place for you that meant a lot?

STUHLBARG: It was everything I wanted it to be. I had great seriousness about the work. I had done my first real Shakespearean lead. I got to play Romeo when I was at UCLA, and I played the old man in Fool for Love, Sam Shepard’s play. I found these worlds to be so evocative that I would just give myself entirely to them. I kind of thought of Juilliard as an “acting army” in some way. It was a great place to apply great discipline to whatever the craft was, depending upon whether it was a Chekhov play, a Shaw play, a Shakespeare play, or a modern play.

GUADAGNINO: So the discipline changes in comparison to the pieces you’re doing?

STUHLBARG: Absolutely.

GUADAGNINO: What is Chekhovian discipline?

STUHLBARG: Well, what I learned about Chekhov was that the sky is the limit in terms of intentions, but there’s kind of two things going on at once. Someone might be breaking down and having the worst day of their life in front of the stage. At the back of the stage, there might be someone walking behind them with squeaky shoes on. Chekhovian seemed to be this juxtaposition of both humor and tragedy. That became a sweet spot, because I felt like my sense of humor saved me throughout my life in many instances.

GUADAGNINO: And in learning those things at Juilliard, did you learn how to become an artist, and how to live in the company of other artists?

STUHLBARG: I don’t know if I learned that in drama school so much. I think at Juilliard, their idea was to put together a company of actors. You wouldn’t have eight leading men and eight leading women, you would have a variety of people who were meant to do plays together for the four years that you’re training.

GUADAGNINO: And so then, after you finished Juilliard, you felt that you were going into a career in theater?

STUHLBARG: I just wanted to go out there and apply the things that I had learned.

GUADAGNINO: Which was theater?

STUHLBARG: Which was theater, yeah. We didn’t have any on-camera acting classes. That wasn’t what they wanted us to think about. They wanted us to think about the craft of developing character and applying the tools that they had taught us and understanding that the tools were just that—they were tools. They were not meant to be the good speech that you’re meant to learn or to speak a particular way. It was something that could be applied to a particular job or production or play, not something to be done all the time.

GUADAGNINO: So it’s not a mold.

STUHLBARG: No, it wasn’t.

GUADAGNINO: Afterwards, you spent time with the great mime, Marcel Marceau. Was this after Juilliard or later?

STUHLBARG: That was at UCLA before I went to Juilliard. That was an opportunity that had started two years before I joined, that you could audition for this.

GUADAGNINO: Were you aware who Marcel Marceau was?

STUHLBARG: I knew who he was because simply from a Mel Brooks movie. There was a film he made called Silent Movie, in which Marcel Marceau said the only word in the entire movie, which was kind of part of the fun. But so, four of us went to the campus at the University of Michigan, and studied there with him. We took classes with his students, as well as with him a couple of times a week. And he taught us the language of how he tells stories alone, only with his body on stage. It’s a great, great discipline. And I learned mostly that summer about how severe a discipline it was, and that I don’t think I could ever become one. I don’t think that was really my aim to begin with. It was just another influence to perhaps tuck in my back pocket and maybe it would come in handy sometime.

GUADAGNINO: It became handy?

STUHLBARG: It did, in some ways. It’s not because I can use it in anything that I have really done, but it’s about mastery of your body. It’s about complete relaxation combined with an awareness of who you are in space, about how the slightest gesture can help tell a story. So you never know when that can come in handy. I understood how complete it was and grew to have an appreciation for dancers, but it wasn’t something that I was as passionate about as language.

GUADAGNINO: But clearly it helped you getting into Juilliard, right?

STUHLBARG: I don’t know, but I presume so. I presume they saw that on my resume and thought, “That’s interesting.” Actually, one of our movement teachers, Moni Yakim—who was renowned for developing the physical movement for Robocop—taught these classes at 8:00 in the morning where you were asked to push yourself beyond which you can think you can go. You’re standing on your tiptoes, you’re running around the room entirely for an hour on your toes, throwing yourself onto the floor and picking yourself right back up again. So you develop a great sense of flexibility and movement and—

GUADAGNINO: And pushing limits.

STUHLBARG: Pushing your limits, and also stretching your body as far as it can go, and then quoting Shakespeare. So your voice is coming out.

GUADAGNINO: Everything you’re describing I see in your work.

STUHLBARG: It all informed who I am, I guess, all that physical stuff. Did you know early on that you wanted to be a filmmaker?

GUADAGNINO: Yeah, I wanted to be a filmmaker very early on. I probably was five, four.

STUHLBARG: Really?

GUADAGNINO: Yeah.

STUHLBARG: How?

GUADAGNINO: If you ask my mom, she’ll tell you. I was saying that I wanted to be a director when the question was asked to me when I was a kid.

STUHLBARG: Oh my goodness. Wow.

GUADAGNINO: I saw a few movies growing up that made a huge impression and I was always asking myself, “What was the technicality that made it so I could see the vastness of David Lean’s desert or the sheer lightness of Richard Donner’s Superman on that screen?” That became a very active, relentless process of thinking and searching for information.

STUHLBARG: The mechanics of building what you saw?

GUADAGNINO: The magic of it. What I was seeing and why I was so deeply invested in what I was seeing. But at the same time, it made me a voyeur, someone who likes to look at things.

STUHLBARG: Me too. Were your parents encouraging of it as well?

GUADAGNINO: My mother was. She gave me my first camera when I was like 10.

STUHLBARG: Wow.

GUADAGNINO: I asked for it. She bought it secretly because my father didn’t want us to spend money. But when you did Juilliard and UCLA, what year was it?

STUHLBARG: UCLA was ’86 to ’88. Juilliard was ’88 to ’92.

GUADAGNINO: Was that a different United States of America?

STUHLBARG: Everything was different in New York at that time. At least in my rose-colored memory of things, everything was cheaper. You could still get a burger and fries across the street for nothing, and a hot dog across the way, and you could survive. They housed us at the YMCA for the first two-and-a-half years. There was no sense of it being at a place of elite people. It was a community. It was gritty. It was fun. It was lighthearted. There were still porn theaters on 42nd Street. It was before all the gentrification. Everything was very much more local and friendly.

GUADAGNINO: And yet able to create imagery for the world.

STUHLBARG: Yeah. But I think the world was kind of captivated by the seediness that was captured in a lot of those ’70s films, in Mr. Scorsese’s films or in—

GUADAGNINO: [William] Friedkin.

STUHLBARG: Friedkin, absolutely. It became alive, and it was part of the mystique of what that place was about. There was open sexuality, there was danger, but there was great art there.

GUADAGNINO: So when did you meet cinema? Not as a viewer, but as a performer?

STUHLBARG: Mostly from Joel and Ethan Coen. The opportunity I had to work with them on A Serious Man.

GUADAGNINO: Do you feel that your career is intertwined with theater no matter if you do films?

STUHLBARG: Absolutely. I needed to build my confidence. I needed to understand that I was capable of taking large roles onto my shoulders and proving to myself that I was capable of being able to guide a company or tell a story.

GUADAGNINO: Where do you feel the accomplishment is more for you?

STUHLBARG: It could be in either medium, honestly, but I think what the camera affords is pure honesty. It’s a craft to learn absolute relaxation in front of a camera. Whereas if you’re sharing your spirit with several hundred people or 1,000 people, there’s an openness. Sometimes I find myself wanting to push the energy further to see if I can get more energy back from them. It is a group activity, it really is. Whereas with cinema, you can think something differently and it will be registered. There’s a whole other beauty to it.

GUADAGNINO: Because you’re such a generous actor, because the pivot of a movie can be not in the forefront sometimes. Like our movie Call Me By Your Name, but even Bones and All, the moral catastrophe of the movie is these people not being able to fit in with anything that is societal. And so it’s a privilege. But I think–

STUHLBARG: The privilege is mine.

GUADAGNINO: Both. And I think we’re just getting started.

STUHLBARG: What a delightful thought. Thank you.

GUADAGNINO: It is. It is delightful because it is alive in movement. Thank you.

STUHLBARG: Such a privilege. Thank you.