IN CONVERSATION

Is Catholic Guilt the Key to Understanding Derek Cianfrance?

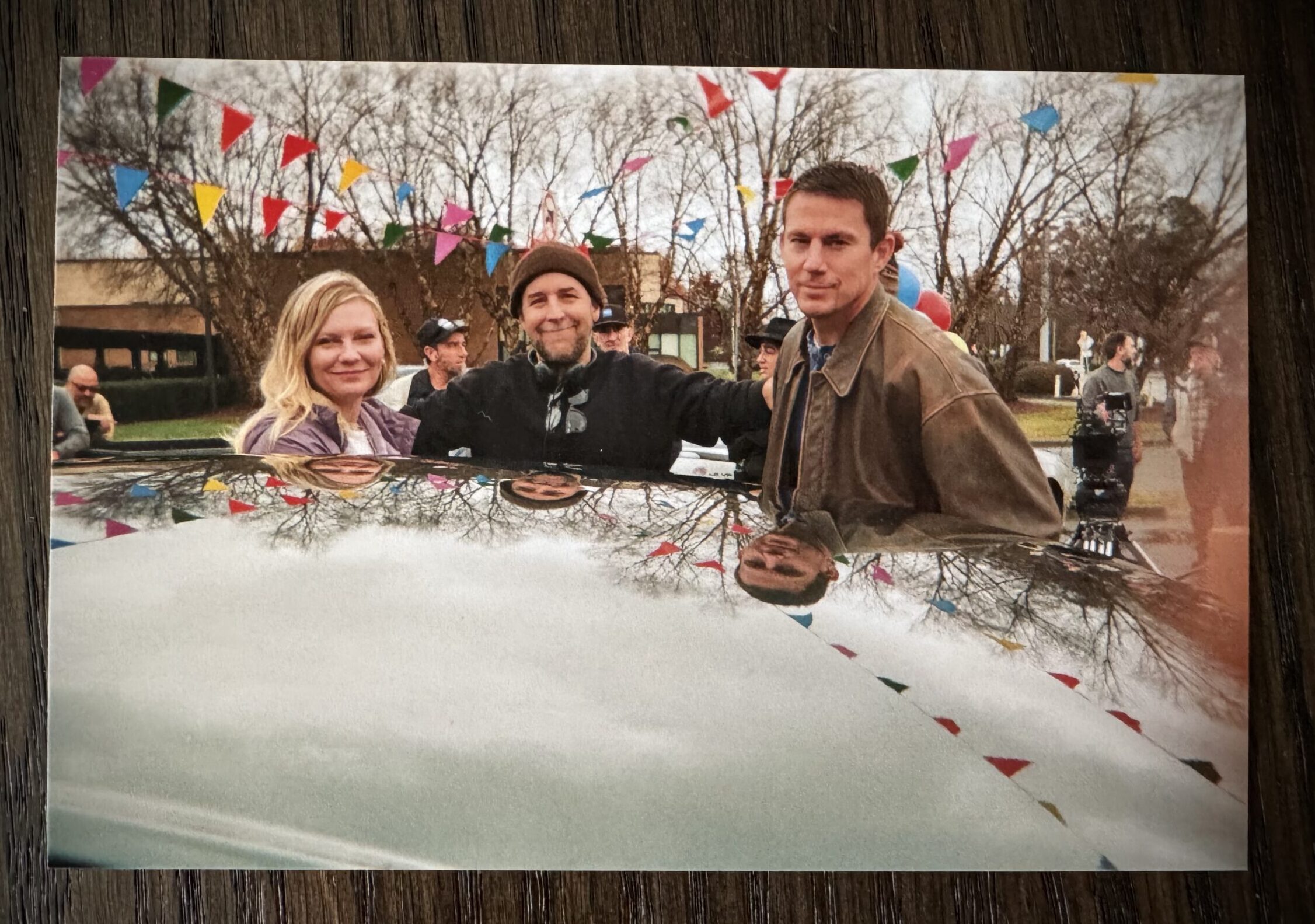

Nicholas Hoult identifies only as a “semi-pseudo Freud,” but that didn’t stop the Academy Award-nominated filmmaker Derek Cianfrance from looking to the Superman star for a diagnosis when the two got together earlier this month. “In all my movies there’s fathers raising kids that aren’t their biological children,” the 51-year-old director said. “I still don’t know what that’s all about, Nicholas. And my therapist hasn’t been able to figure it out either.” The theme recurs in Roofman, Cianfrance’s tender and action-packed biopic of Jeffrey Manchester, the former Army soldier who robbed a litany of McDonald’s locations in the early 2000s. Now in theaters, the film stars Kirsten Dunst and Channing Tatum, who the Blue Valentine director felt was uniquely equipped to capture the sadness of a serial burglar estranged from his children. “It’s really the story of a sad clown,” he explained. “You’re laughing at him, but there’s so much pain in his life.” In their Zoom session, Cianfrance and Hoult attempted to get at the source of that pain, and so much more—including fatherhood, delusion, true crime, and the unparalleled thrill of watching live sports.—SIMON DWIHARTANA

———

NICHOLAS HOULT: Derek, I’m so excited to talk to you.

DEREK CIANFRANCE: The feeling is mutual. Thank you so much for doing this. I’ve been wanting to meet you for a long time.

HOULT: I’m a massive, huge, huge fan—and that’s not exaggerating—of your work. I’ve been bugging my agents for what feels like years to try and meet you every time I’m in New York. And then, finally, I’m getting to meet you under these circumstances, which I guess is slightly different. I’ve got some very hard-hitting questions for you.

CIANFRANCE: Let’s go.

HOULT: I got to see Roofman, which I absolutely loved. I had to watch it on a link because I can’t get out of the house at the moment, I’m afraid. But I’m really looking forward to experiencing it with an audience, because it feels like probably the most comedic of your films. I guess my first question for you is how you first came across the story, what drew you to it, and what you felt like you wanted to explore with his story.

CIANFRANCE: Well, I felt like the last 15 years that I’ve been making movies about legacy and ancestry and inheritance and the sins of the fathers. And with I Know This Much Is True, I just felt complete. The process of making I Know This Much Is True felt like a vacation. With the cast and team I had, it just felt so complete. It came out right when the pandemic hit, and I remember I had so many friends that called and told me that they had to shut it off when Mark Ruffalo cut off his hand, which is in the first minute of the series.

HOULT: [Laughs]

CIANFRANCE: So I realized that not many people got to see that. My wife’s a comedian, and she has this belief that people need to laugh. And I see that in her life as a comedian, she’s way more serious than I am. Being a person that’s like me, obsessed with tragic stories, I feel like I laugh in my real life more. My imagination is dark, but my consciousness is very light and optimistic. So I felt like, well, maybe comedy and tragedy are flip sides of the same coin and that maybe, with this movie, what I could do is flip that coin in the air and see the comedy face and the tragedy face spin and you wouldn’t know which one you were looking at. I was also thinking about how if you slip on a banana peel and fall on the ground, it hurts, it’s painful—but people laugh. So I was trying to find a tone and character that lived in that space. I’m excited for you to see it in the theater, because in my experience with the movie, it’s just always so much better with a group of people. You’ve had that experience with your own work, right?

HOULT: [Laughs] Oh yeah, I’ve had that a few times.

CIANFRANCE: What’s it like for you when you watch your stuff?

HOULT: Very painful. [Laughs] I’m my worst critic, so it’s normally just me sitting there being like, “I could have done that better, I’d like another try at that.” But I love comedy because it comes closest to the sadness, I guess, of life. There’s something about this movie where you really run the gamut of the emotional spectrum and you handle it with a deft touch. Because it is very funny and bizarre at times, but then you have this wonderful romance and heartfelt loneliness there as well. In terms of [Jeffrey Manchester’s] story, how did you first come across it? When you were researching and writing, was there anything that you felt romanticized too much? Because obviously, you want people to like and care for your protagonist, but were there moments where you were like, “Hang on, I’m making him too likable in a way”?

CIANFRANCE: Yeah, it was a difficult tightrope to walk. First off, all these true crime things about serial killers and murderers drives me crazy. I can’t watch them. If you look back at my movies, there’s not a lot of violence in any of them. I mean, there are some in I Know This Much Is True, but there’s only one gunshot in [The] Place Beyond the Pines and it has a resounding effect over the course of the movie. I hate violence, I just despise it. So the thing that intrigued me about this character of Jeff was that here was this hardened criminal who appeared to hate violence as much as I did. He would lock people in freezers at McDonald’s, but make sure they had their jackets. And here was a guy who was an Army vet who had served nine years in the military. And when he breaks out of prison, he doesn’t choose to live in the woods and survive off of grubs and rainwater—he decides to live in a toy store and eat baby food and candy. This is a guy who had a ticket to his freedom in the car seat next to him and decided to turn the car around when he got a call from his girlfriend so he could go have dinner with her one last time and tell her goodbye to her face.

It struck me that this was a guy who would’ve been a better criminal if he’d had less of a heart, and it was his humanity that in fact made him a bad criminal. And at the same time, even though this is a guy living and being an idiot in a toy store, he’s also made a huge tragedy out of his life. And in doing the research on his story, I couldn’t ignore the tragedy. For me, the first question was like, “What about your kids? What happened to your kids?” And the months and months that I would speak with Jeff on the phone, the more and more I realized that once you rob 45 McDonald’s and get sentenced to 45 years, you no longer have any agency over being a father and being in your kids’ life anymore. And I think Jeff realized that he no longer had a choice in that matter. He did break out and spent a day in a tree watching his kids play, but he knew he couldn’t hug them and do the things that dad is supposed to do anymore. His plan was to go to a country with no extradition laws. And I asked him, “Well, how do you go to Venezuela to see your kids when your kids are in America?” It didn’t make any sense. So there was this huge tragedy that was born from his choices that I felt like the movie had to really acknowledge. And I think that’s where you get the tone of the film, and where Channing [Tatum] does so well in the movie—it’s really the story of a sad clown. You’re laughing at him, but there’s so much pain in his life. I remember Channing was screaming when he first read the script, “Don’t do that!”

HOULT: [Laughs]

CIANFRANCE: This character made a couple of bad choices, and then what ended up happening was that all he had were bad choices. I don’t know, I guess all the characters in my movies get trapped in their own bad choices. Maybe it’s my Catholic upbringing.

HOULT: You think that’s where it comes from? [Laughs]

CIANFRANCE: Probably, yeah.

HOULT: Channing’s performance was brilliant, because one of the things that I really felt was the loss of his children and the desperation in trying to connect to Kirsten’s [Dunst] character’s children. Was that something that you really focused on, the desperation of trying to recreate what he had lost?

CIANFRANCE: It was one of the reasons I cast Channing. I took a six-hour walk in the park with him, didn’t tell him anything about this story, just got to know him. And it was clear to me when I spent time with him that his daughter was the most important thing in his life, and he was trying to navigate custody and what it means to have shared custody over your kids, and I thought he could understand that pain, that desire of wanting so badly to be a parent. My life has been centered around my children. That’s why I only make a movie every five years, because I’ve been focused on trying to be a dad and be home. I think this theme plays out in a lot of my movies, and I wasn’t aware of it. But I had met with Ryan Coogler some years ago and he said, “Hey, D, how come all the guys in your movies are raising children that aren’t theirs?” And I actually had no idea that in all my movies there’s fathers raising kids that aren’t their biological children. I still don’t know what that’s all about, Nicholas. My therapist hasn’t been able to figure it out either.

HOULT: Well, let’s figure it out now. [Laughs]

CIANFRANCE: [Laughs] Okay, Dr. Nicholas.

HOULT: [Laughs] I’m a semi-pseudo Freud. There’s something beautiful and selfless about that, right? I feel like so many men in this world would not be willing to take on that role. But that’s something that’s deeply warm about your characters that makes you understand the type of men they are despite the choices they make. But I’m still not sure why you’re drawn to them.

CIANFRANCE: I don’t know either. I don’t know when I’m going to have that aha moment. Maybe on my deathbed I’ll realize why, and then I won’t be able to tell anyone. But you know what? There’s a great quote by [Robert] Bresson. You know that Bresson book, Notes on the Cinematographer?

HOULT: I haven’t read that.

CIANFRANCE: It’s like a nice little bible for making movies. Okay, here it is: “Hide the ideas, but so that people find them. The most important will be the most hidden.”

HOULT: Ooh. Is that something you’re consciously thinking of when you’re making things?

CIANFRANCE: With this movie, I was thinking a little bit about hiding the spinach. You can serve people a big plate of spinach, and spinach is very good for you—I love spinach—but I also understand the instinct to put some spinach in a burrito so you don’t see it. All you taste is the bacon and the beans and the chorizo, all the fatty things.

HOULT: Yeah. What were the movies that you loved? What inspires you, I suppose, day-to-day? Obviously being a father and spending time with your children is a big commitment. For me, as a father, I get a lot of inspiration and energy from my kids. How many do you have?

CIANFRANCE: I have two boys. I have a 21-year-old and an 18-year-old.

HOULT: Oh, fun. Are they in college or high school?

CIANFRANCE: They’re graduated, they’re both on their journeys of life right now. They’re in their vision quests.

HOULT: Have they shown any interest in creative arts like you?

CIANFRANCE: My youngest is a very, very accomplished wildlife photographer.

HOULT: Oh, cool!

CIANFRANCE: He started when he was 6 years old. I bought both my boy’s cameras on a road trip and my oldest son would only shoot cars while my youngest son would only shoot birds, and he just kept going with it. He goes on these adventures where he saves money to take trips and go hike eight miles into the tundra of Greenland to photograph a muskox. It’s super scary for me, because he’s going into the wild and he’s from Brooklyn, but he’s coming back with amazing images.

HOULT: I love when people find their calling very early in life. You said he started at 6 years old? I think that’s incredible.

CIANFRANCE: I know. It’s very lucky.

HOULT: I feel very lucky that I found acting at a young age.

CIANFRANCE: How old were you?

HOULT: I did my first play when I was three and then my first film when I was five, so I was doing it pretty young. When did you come to directing?

CIANFRANCE: Also when I was very, very young. I remember my brother’s birthday party, he had a slumber party. I think I was six or seven or eight, I’m not quite sure, but he rented a VCR and they rented Creepshow and Airplane II: The Sequel.

HOULT: Oh, awesome.

CIANFRANCE: Making Roofman in a toy store felt so similar to being a kid and playing in the sandbox with a camera or a tape recorder with my friends. It just felt really a lot like play.

HOULT: When you’re playing like that, is a lot of what’s on the screen scripted or do you guys improvise a lot?

CIANFRANCE: By the time I’m on set, I have a script—in this case, like, 30 drafts of a script, and part of my practice is trying to visualize and watch the movie in my head. But at the same time, the last thing I want to do is see what I’ve seen in my head when I get on set. Without actors, I’m just a person who has ideas, a person who’s a delusional dreamer. And when actors appear in my world, all of a sudden these things start to feel alive. So I tell all my actors to surprise me. If we ever have the chance to work together, my two rules are: do anything you want to do, and do what I ask you to do. I spent so many years making docs, so I’m always trying to think of how to put actors in situations where they can live and surprise me. I don’t know, how do you prepare if you have something to do tomorrow?

HOULT: Tomorrow? It’s too late.

CIANFRANCE: [Laughs]

HOULT: I try and describe it as, I cast a wide net to begin with and then it just narrows down to the point of filming so that when you get on set, you’ve got all this history and ideas of books, music, whatever it is that’s inspiring you and is useful for the story, for the character, et cetera. And then you get onto set and all that stuff goes out the window and hopefully you’ve prepared enough where you have the confidence. It’s almost like what you said earlier, you’ve got this image in your head. I have an idea of this character and I’m trying to make it as much of a reality for me as possible so that when I get to set and I’m being asked to do things or act things out, it doesn’t feel like I’m pretending. I think that’s the trick. It’s kind of a self-delusion thing, where if you put in enough work and prep, then you can just do the thing and it feels real.

CIANFRANCE: Delusion is a good thing, I think delusion is so important for what we do. You don’t have to name names, but what’s been the best experience you’ve ever had being on set?

HOULT: The best experience? One that always comes to mind, and this isn’t even a set experience, was the audition for Mad Max: Fury Road. We spent six hours auditioning for Mad Max, and only in the last half-hour we did a scene. The rest of it was all exploratory games and observation techniques and physical theater protocol kind of things. I walked out of that audition going, “Okay, well, even if I don’t get the part, I’ve had an experience and felt like I’ve learned something.”

CIANFRANCE: Can I ask you real quick? Because I love George Miller so much. When you got on set, what happened? Did you maintain that? Because his films feel so controlled, but there seems to be life and chaos that’s creeping into them too.

HOULT: George is very calm, first of all. I remember one day sitting in the car, waiting to do a take, I was like, “Look at this, George. We’re surrounded by these vehicles in the desert. You’ve been waiting 17 years to make this movie. You must feel incredible.” And he said something about how he was obviously very excited that it was finally happening, but he still had to be objective about it and not get carried away with it and still make something that was accessible for everyone else. But he’s very calm and aware and he’s got time to talk calmly to people. He would send hours of videos before we started shooting. We would have the whole character’s life from birth onwards. And then the frenetic energy comes from the environment. I think something that’s wonderful about George is that it wasn’t necessarily only a script—it was basically a storyboard. And that’s something I wanted to ask you, actually. When you’re imagining this film and it’s playing out in your head, do you storyboard or do you find the shots on the day?

CIANFRANCE: On Blue Valentine, it took me 12 years to make that movie and I storyboarded every shot—1,224 images—because I had to have something to do for those 12 years. And when I got on set, I threw all of them away. Well, I left them at home. [Laughs] I still have them.

HOULT: I love that movie so much, by the way, it’s just incredible.

CIANFRANCE: Thank you.

HOULT: But when you put the storyboards away, have you ever gone back and watched the film with the storyboards? Does it line up somewhat, even though you weren’t using them?

CIANFRANCE: Not at all on that one, but I haven’t looked. But when I did those storyboards for Blue Valentine, I was really influenced by Russian cinema of the ’40s, ’50s, ’60s, like [Mikhail] Kalatozov. Have you ever seen I Am Cuba or The Cranes Are Flying?

HOULT: I have not.

CIANFRANCE: They’re crazy movies that are just technically so next-level, and they’re all about how just badass the cinema is and how incredible the shots are. And when I was writing those storyboards and didn’t have actors, all I had was my imagination and my command of the grammar of cinema. So what the storyboards did was show what the grammar of cinema would be. But when I went to make Blue Valentine, I was like, “I’m going to tell this story through actors,” and that’s been the choice I’ve made through all of my films. Because I realized, as a viewer, that’s what I watch. When I go to a movie, obviously I look at the frame, I look at the composition and the light. But above all else, I look at actors. So my rules were that this is going to be a duet. So half of it, I was going to shoot on film, and half of it I was going to shoot digitally. The part where they’re falling in love was all going to be shot handheld with one lens, a 50-millimeter lens, whereas the present would be shot with two cameras at all times on tripods with 290-millimeter lenses. So one story was going to be about this embrace of the camera and the other was going to be like you’re shooting lions. I wanted to abandon the actors in the scenes. So I was no longer with Ryan [Gosling] and Michelle [Williams], I was across the room watching them, because I wanted one to feel like a long-term memory and I wanted the other to feel like short-term memory. One had no lighting, the other was more controlled—so it felt like two different worlds. Once I had those rules about how the camera could and couldn’t interact with the actors, it gave a point of view to the cinematography. But I also wanted to be invisible. I don’t want people to watch the movie and think of me at all. I want them to think of the actors.

HOULT: Hearing you explain that to me now, I’m playing the movie back in my mind. I see that now in the shots and I understand it, but it’s never something that I was ever aware of consciously as an audience member.

CIANFRANCE: I learned this from a student feature I made called Brother Tied. I went to a very experimental avant-garde film school and I had heard that The Wild Bunch had 1,600 edits in it, so my whole point to making this movie was to make a movie with more cuts than The Wild Bunch, and I did. I beat The Wild Bunch in terms of how many edits I could make in a movie.

HOULT: How many did you make?

CIANFRANCE: Like, 1,640.

HOULT: [Laughs] Final question: how do you feel now that the movie’s out into the world? I want to know what you’re being inspired by at the moment, what you’re listening to or watching or seeing. Do you feel this is the beginning of a new era for you?

CIANFRANCE: My kids are getting older now, they’re not around as much, so I have more time to stay busy. I will say that I feel relieved, because this movie was really, really hard to make. I think when you tap into that conscious optimism, all that was left over in my tank was my dark imagination. So I might go back to the darkness again. [Laughs]

HOULT: [Laughs]

CIANFRANCE: I have this one project I’ve been working on for 18 years, so I hope that gets going now. And what am I inspired by? [Pauses] I’m inspired by NBA basketball, specifically the Denver Nuggets, specifically Nikola Jokić.

HOULT: That’s your team?

CIANFRANCE: Yeah.

HOULT: Jokić is unreal. I love watching the videos of Jokić when he goes back to Serbia with his horses and he’s just so happy. I love seeing that.

CIANFRANCE: I haven’t missed a dribble of a Denver Nuggets basketball game in six years. That’s like, real drama to me. When I watch the Denver Nuggets basketball game at midnight, my heart is racing.

HOULT: Oh, dude. I measured my heart rate once. I’m a basketball fan. I tore my ACL playing a few months back, so I just had the operation three weeks ago. I’m sitting here in a straight-leg boot and I can’t walk at the moment.

CIANFRANCE: Damn. Oh goodness.

HOULT: But I’m a Lakers fan, sorry to say, although I was at the game when Denver beat us in the playoffs two years ago to knock the Lakers out, which was heartbreaking but also probably deserved.

CIANFRANCE: Damn.

HOULT: But dude, I measured my heart rate once watching a boxing match. They rang the bell to start the fight and my heart rate was at like 130. I was like, “Dude, I’m just sitting here, I’m doing absolutely nothing, I’m not in the ring, why am I getting such an adrenaline dump from watching sports?” But there’s something about live sport that taps into some sort of visceral human… I don’t know.

CIANFRANCE: Yeah. I don’t think AI is ever going to replace it.

HOULT: I hope not.

CIANFRANCE: I don’t know how it can. I’m obsessed with it. We’ll have to watch a game someday.

HOULT: Let’s watch a game., That’s a good way to ramp things up.

CIANFRANCE: All right, deal.