Jean-Claude Carrière’s Theater of the Absurd

The work of Jean-Claude Carrière twists the mind in on itself. The French screenwriter, novelist, and playwright’s mark has been authoring perception-teasing scenarios of bizarre circumstance, including a wealthy Frenchman lustily obsessed with a young woman evasively played by two actresses (Luis Buñuel’s That Obscure Object of Desire, 1977); a 10-year-old boy who insists he is the reincarnation of a widow’s dead husband (Jonathan Glazer’s Birth, 2004); or a diplomat’s wife’s love affair with a chimpanzee (Nagisa Oshima’s Max mon amour, 1986), elevating the absurd into cinematic objects of lurid fascination that stoke the subconscious.

With over 140 film writing credits and a number of novels and plays to his name, Carrière has adapted Proust and Milan Kundera for the screen, and partnered with some of European cinema’s biggest auteurs, including Jean-Luc Godard and Louis Malle. But his 19-year collaboration with the Spanish surrealist Luis Buñuel, with whom he created six films, including Diary of a Chambermaid (1964), Belle de Jour (1967), The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972), and That Obscure Object, has come to be regarded as some of his most provocative work. But Carrière continues to work prolifically: his latest book, Croyance (translated, Belief), was released in March, and a collaboration with Philippe Garrel, In the Shadow of Women, premiered last month at the Cannes Film Festival.

Growing up in the south of France in a family of winemakers, Carrière published his first novel, The Lizard, in 1957, and began making movies after a meeting with Jacques Tati to novelize the director’s films. Starting tonight, the French Institute Alliance Française’s CinéSalon program is hosting the series “Jean-Claude Carrière: Writing the Impossible,” a survey of Carrière’s career featuring nine films, including Malle’s May Fools (1990), Godard’s Every Man for Himself (1980), Max mon amour, Birth, Andrzej Wajda’s Danton (1983), and Jacques Deray’s La Piscine (1969), starring Romy Schneider, Alain Delon, and Jane Birkin.

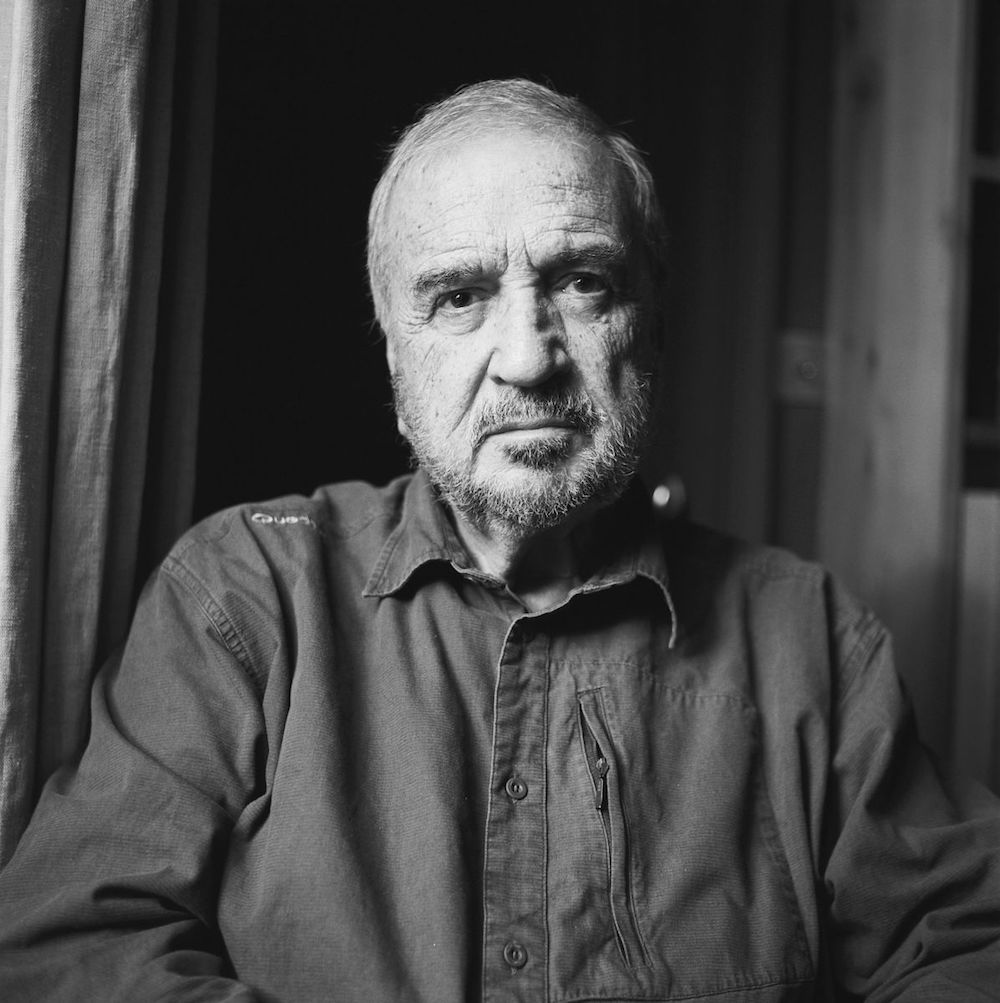

When we called up the 83-year-old last week at his home in Paris, he was quick to set the scene on his end of the line. “It’s six o’clock in the afternoon, the weather is beautiful. Everything is fine and calm and my two cats are with me,” he said. We dove in.

COLLEEN KELSEY: You began as a novelist, but when you were a child did you ever think that you would grow up to work in the movies?

JEAN-CLAUDE CARRIÈRE: Before I wrote a novel, I was already a movie fan. I was extremely interested by the cinema since I was 10 years old. But, when you publish a novel, it’s easier to make it first. It’s less costly, and the publisher can run the risk to publish a young author. To run the risk of producing a young director is much more difficult.

KELSEY: Do you remember the first film that you watched that affected you creatively?

CARRIÈRE: It was two American films, but I don’t know exactly which one came first. One was Snow White, and the other one was with Gary Cooper called Anthony Adverse, which is totally forgotten today. I still remember some images. They’re the first films I ever saw.

KELSEY: You co-directed the short Heuereux Anniversaire (1963), which ended up getting an Oscar. That must have been a surprise that early in your career.

CARRIÈRE: You know, when I came to the office and the producer was jumping out of joy: “We have the Oscar! We have the Oscar!” I asked, “But what is the Oscar?” I didn’t know.

KELSEY: Was it a conscious choice to not move forward as a film director?

CARRIÈRE: I was tempted to be a director and belong to the generation of the New Wave. All my friends became directors. But I had already published two books; I felt that I could also work in theater. The moment you are a movie director, you can’t be considered a writer. You have the little pin, you have the star on your shoulder: “Director.” You can only make films. I was born, and I suppose you were born, in the first century to have invented new languages—cinema, radio, television. I was attracted by all these new ways of writing when I was 22, 23. After I turned 30, when I had to decide if I wanted to make a film or not, I decided to be a screenwriter, so that I could be able to write books and work in many other fields, which happened. But of course, I’m working closely with the director all the time, and I have to know about the technique of the film—it’s absolutely necessary. We work facing the director. If the director starts talking technique, and you shrug and you don’t know what he’s talking about, he doesn’t need you. You have to be at the same level.

KELSEY: Is it important to you to share the same vision as the director?

CARRIÈRE: I always do it, because I see the director facing me. Most of the time, it is not always possible. Of course, a screenwriter, like any writer, has to go through long moments of solitude. Solitude is the best friend and the best enemy of any writer. But, as often as possible, I like to face the director. When I am offering something—an idea, whatever—to see the immediate reaction on his face, on her face, if he goes, “Yes. Well, that’s interesting,” that doesn’t mean he likes it. If he doesn’t say anything, but looks at me, bending a little towards me, and says, “Then?” At that time, I know he’s interested. That reaction is priceless, because I know he is the one that is going to make the film. Quite often the screenwriter has to guess what exactly the film is that the director wants to make. Sometimes the director doesn’t even know himself. You have to help him find the right thing. That was the case with Buñuel. At the beginning, he was looking around in many different directions, and finally when we went the right way, we felt it.

KELSEY: When did you first meet?

CARRIÈRE: In ’63, at the Cannes Film Festival. We had lunch, and the first question he asked me was, “Do you drink wine?” I said, “Not only do I drink wine, but I’m from a family of winemakers.” “Oh, really?” he said. That was a really good point. Two other points were that I had already written a film, which was a comical film, almost without words, in the tradition of American slapstick and surrealism. There is a secret, but very strong connection between American slapstick and surrealism—exactly the same period, and very often the same inspiration. I had also written a documentary about the sexual life of animals. Buñuel, when he was a student, studied entomology. Until the end of his life he could call any insect by its Latin name. These two points were a correlation between the two of us. We had a very nice lunch. I flew back to Paris without even going to the festival. A week later, the producer called me and he said, “Pack. You’re leaving in two days.” That was a fantastic moment.

KELSEY: Where were you going, Spain or Mexico?

CARRIÈRE: At that time, in Spain. [We worked] half in Spain and half in Mexico, and once or twice in Paris. Luis was eager to go back to Spain at that time, because he had a Mexican passport, but he lived in Mexico. We had a very beautiful place in Mexico to work—very lonely, and in Spain, a beautiful old convent with some monks in the mountains. Working with Buñuel was living with Buñuel. No wives, no friends, no visitors, nothing—totally concentrated on the work for weeks and weeks. That was the absolute rule—like two monks.

KELSEY: I read a bit about the three-second rule you two had when brainstorming ideas—you would have three seconds to say yes or no to an idea.

CARRIÈRE: Yes—the veto. Once somebody says “No” the other one had no right to discuss. It was a Surrealistic tradition. He was looking for the first instinctive reaction of his partner without any reasoning. When you start reasoning, you can justify anything. But when you give a very immediate and instinctive reaction, you cannot. You cannot cheat. From time to time, I tried to cheat: of course, to say yes when I was thinking no, and so on. But he knew it. It’s a very beautiful way of working; one trusts the other. If not, there is no way to work together. But we worked together for 19 years.

KELSEY: A lot of critics have written with the intent to decode his films. Of course there’s symbolism, but I think that sometimes that understanding the surrealism of Buñuel is more instinctual than something to be analyzed.

CARRIÈRE: Buñuel hated the word “understand.” “There is nothing to understand in my films,” he used to say. There are things to watch, and to listen to, but nothing to understand. Of course there is a story; there are characters. But to analyze what it means, you are lost. You are losing your time. You should use your time in any other way but understanding. I could tell you a silly story. It’s a dirty story, you don’t mind?

A very famous Mexican psychoanalyst wrote a book called The Eye of Buñuel—El Ojo de Buñuel—where he was explaining everything: this image means this, and this and this. I read a few words from the book with Buñuel in Mexico, and one day I found myself in Paris, in the Mexican Cultural Center, facing the psychoanalyst. I said to him after a moment, “I have something to tell you from Mr. Buñuel, because maybe you don’t know that in Spanish the word ojo means ‘eye’ and also means ‘asshole.’ [laughs] Buñuel told me you wrote a book about Buñuel’s asshole.”

KELSEY: [laughs] Do you think that your storytelling sensibility is predisposed to Surrealism and the uncanny?

CARRIÈRE: I don’t know, but I read the manifestoes of the Surrealists when I was 14—too young to read it. But, the book struck me. Then, little by little, I was much more attracted by the Surrealist way of looking at life, than by the classical one. Maybe that’s one of the links that did exist between Buñuel and me. But now I’m appreciating everything. I’m going to be 84 this coming year, so I like very much to go back to Shakespeare and Racine, the classics. But, going to Surrealism for a while gives you another way to read Shakespeare. Very often you find Shakespeare’s work, or Racine, passing through the Surrealistic experience, a lot actually. But Buñuel was also extremely attracted by the Russian novelists, especially Dostoevsky, who he liked very much.

KELSEY: How would you describe your work process? Do you keep a notebook? I can imagine you always observing, noting dialogue, how people speak.

CARRIÈRE: That depends on the subject. When you write a book you are alone, and you need solitude, concentration, a sort of silence. But when I’m with a director, I love to go on walks, to sit down at the terrace of the café, to observe, to look at people. Everything comes from life, no doubt about it. When I first met Jacques Tati, I received—I don’t know how to translate exactly—des leçons du regard, “the teaching how to look.” A filmmaker doesn’t look around like anybody, or a photographer, or a painter. They look in a different way. For example, I am a close friend of Julian Schnabel. He lives in my place in Paris, I live in his place in New York. When we go together to see an exhibit, for instance, we went to see a Van Gogh exhibit in Paris last summer, he looks the way a painter looks at a painting. He teaches me. I’m learning from him things that I would never, never have thought about. For instance, when you pose in front of a painter, the look from the painter to you is not the same as the look from the photographer. He’s looking for something else. That’s extremely interesting. Being motionless in front of a great painter for two hours is a real experience. He finds things inside yourself that you ignore.

KELSEY: And he’s also a filmmaker as well.

CARRIÈRE: And a good one. Well, we have a project together, but we don’t know when [it will happen]. We are so busy, both of us.

KELSEY: You’ve said when a screenplay is good it becomes “invisible” within the film. Why?

CARRIÈRE: The screenplay has to disappear at some point. It’s like a caterpillar before being a butterfly. The caterpillar contains the whole film, all the elements, but he doesn’t fly. You give him the possibility to fly. It’s a work that is open. That’s why I like to go to the editing room after the end of shooting. I do not shoot any films that I have not written, so I know the work, and after the turmoil of shooting, you find yourself in the quiet of the editing room. Then the film comes to you in a totally different way.

KELSEY: Have there been films that you’ve written that have never been made that you wish had been?

CARRIÈRE: Of course, yes. Many things that I would have loved to write—many women I would have loved to love. But, my life is quite full. That’s one thing I know I can say. When I think about what was my life—I was born in a very small and poor family. All the dreams of my childhood have been fulfilled, whether I was dreaming of traveling or dreaming of writing stories, I did it. So, if I die tomorrow, I will die happy. But I won’t die tomorrow! [laughs]

“JEAN-CLAUDE CARRIÈRE: WRITING THE IMPOSSIBLE” OPENS TONIGHT WITH THE DISCREET CHARM OF THE BOUGEOISIE AT THE FRENCH INSTITUTE ALLIANCE FRANÇAISE AND RUNS UNTIL JULY 28. FOR SCREENING INFORMATION, VISIT THEIR WEBSITE.