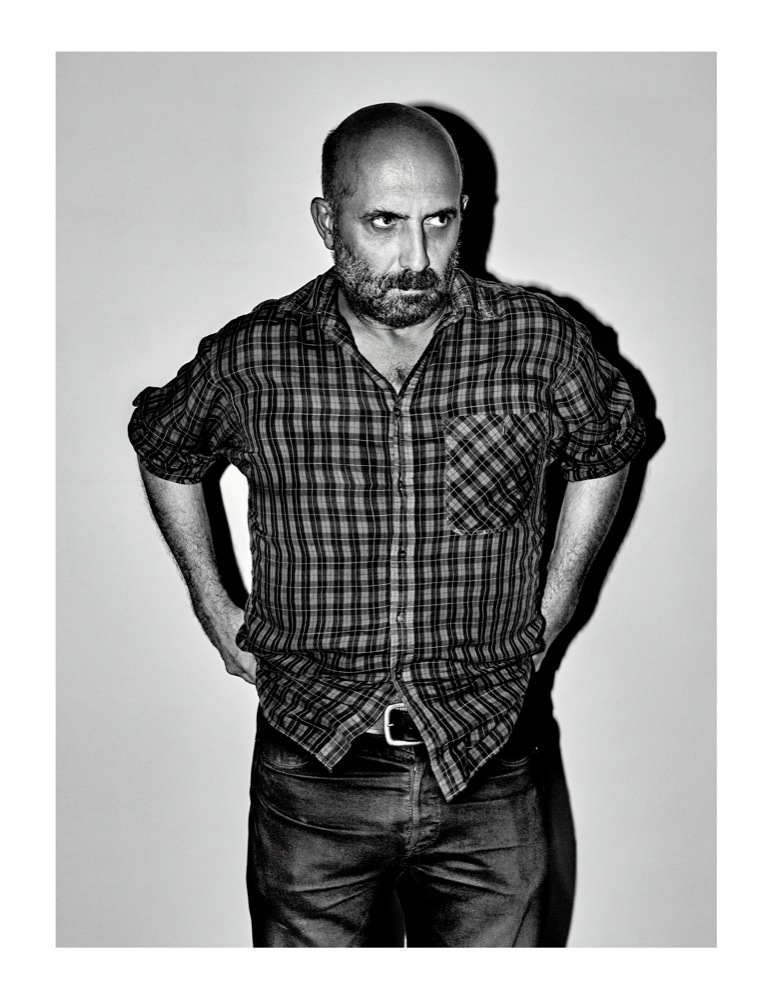

Gaspar Noé

Film’s great provocateur has grown from an irascible enfant terrible—making thumb-biting films about incest (I Stand Alone, 1998), rape and revenge (Irreversible, 2002), and the transcendence of drugs and death (Enter the Void, 2009)—into an incredibly mature, if still rude and puckish, filmmaker of the meditative and heartbreaking romance, Love, out this month.

CHRIS WALLACE: This felt kind of like a new wave film. It made me want to live in a world where people just lie around and do drugs and talk about movies and fall in love.

GASPAR NOÉ: And end up with a baby! [laughs]

WALLACE: There’s a funny point in the movie where the aspiring director, Murphy, announces that he wants to make a movie about sentimental love. I think you’re gently poking fun at young artists and their intentions, but how do your ideas form? Do they come as sort of manifestos like that or do they come as images?

NOÉ: I put in his mouth a lot of things that my friends and I said when we were 25. Murphy talks a lot about what he’s going to make, but you never see him do anything but do drugs and have sex and party. I would say his inspiration comes from movies, like it did for me. And mostly the posters that you see in his room are the posters that I had on my walls—Pasolini’s Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom [1975] had a huge impact on me, as did Eraserhead [1977] and 2001 [1968]. You feel touched by a movie in a good or bad way or you have a strong reaction to something that’s totally artificial, to an imitation of life. But that imitation of life that you see on the screen can affect you almost as if it was real. Like, some people are very sensitive to drugs. They are so sensitive that they don’t even take the risk of taking mushrooms or LSD. Some people are also afraid of watching horror movies because they’re too affected by the images. In my case, I feel very protected when I see a movie. That’s why I like making violent movies or radical movies. When you see a movie, it’s like you’re attending a show of magic in which the magician pulls a rabbit out of a hat. You don’t know how he did it, but a part of you is fascinated, or hypnotized, by what happened, another part of your brain says, “Oh, I want to do the same thing! I want to be that wielder of that magic. I want to be that magician on stage, and do the same thing to other people.” The fact that I’m doing movies now comes, essentially, from being transported to another dimension by 2001: A Space Odyssey.

WALLACE: When you’re working, are you thinking about what you called the imitation of reality, or just about what effect it’s going to have on the audience—whether that is provocation or transportation to another dimension?

NOÉ: From a simple, mammal perspective, you think you’re going to make friends through the movie. You think, “Oh, this kind of humor that I play with will bring people that have a similar kind of humor. I’ll make new friends,” or something. You don’t even think in terms of audience or of money. Sometimes when I make a movie, my main goal is to show the movie to one particular director. I’d be very happy to, for example, show this movie to Scorsese. I know he has seen my last movies and I heard some nice things he said about them. But I would like to see how he, more than most of all the people I know in France, reacts to this movie. It’s not about competing. It’s mostly about someone who did something that blew your mind and you want to see if you can render the joy… Render? Do you say render? To give back? In French, we say render when someone lends you something, when you borrow something, you give it back to them.

WALLACE: With these last two movies you’re sort of in your Sgt. Pepper’s period. It’s all psychedelic electronica. Do you have a vision quest-y, inspirational relationship with drugs?

NOÉ: Some people take drugs in a quest for spirituality. I did a lot of psychedelics when I was preparing Enter the Void but it was almost an excuse—not an excuse, it was real research; I tried to put it on screen. I was going to go and pick up images inside my brain that I thought might be helpful for the movie I was preparing. But on an everyday level, I use alcohol and drugs in general mostly to be in a happier mood, with the people around me. And I notice that I feel safer among women when I do drugs. I would never do drugs with male friends.

WALLACE: Interesting. Are you in love right now? While you make Love?

NOÉ: [laughs] Nah—I don’t want to get into that particular subject, but, yeah, I’m very sentimental …

WALLACE: Do you have muses?

NOÉ: Of course. You can tell that I’m absolutely fascinated by Aomi Muyock [who plays one of the leads, Electra, in Love]. But there’s something in the character of Electra. Electra is not a character that really exists in life, but is a mix of many different situations of different girls who I know. But with her charisma … You mostly feel the charisma of the person, on screen, and for me, she’s like an ideal.

WALLACE: I like what you said about making an imitation of life …

NOÉ: This one is very close to my life. It’s not exactly facts that have happened to me … I’m not always bright. I’m brighter when I’m not drunk; when I’m drunk, I lose part of my IQ. But I wanted the guy to be not a hero, not an anti-hero, but someone who’s bright, sweet, and heavy—someone like most people in your life. My characters are never heroic. They are mostly lost and trying to find the right door to open and they end up opening the wrong doors.

WALLACE: I like thinking about the way art represents life and vice versa. In fact I worry that there are times and cases when I prefer the artistic artifact to real life. I like to escape into that world, rather than live in the moment. Which is kind of like someone preferring pornography to sex.

NOÉ: It’s strange. In the case of this movie, I just wanted to portray things that were the most beautiful from my own personal life. And I always think of moments of love with someone I love. Erotic movies—they don’t even make it anymore. Even the erotic magazines don’t really look like the ones you could find in the ’70s. You have much more extreme iconography of what is sexy. It’s very cold. There’s nothing that links to real life. So that’s what made me think there’s a place to represent love and even sex in a much sweeter way, as most people experience it.