Manolo Blahnik

He creates shoes that are beautiful works of art and that make a woman’s feet seem like they were carved by Bernini. In his simplicity, there issomething surreal.Carolina Herrera

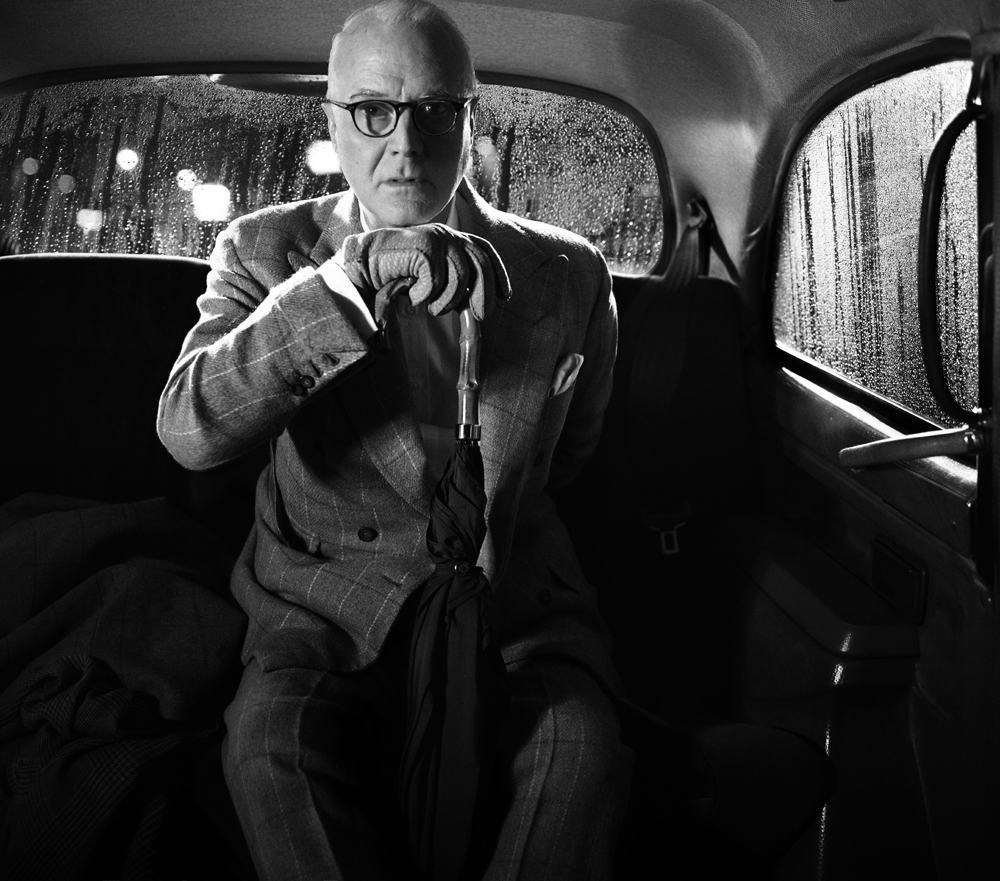

Manolo Blahnik glares out a window of his high-rise headquarters just off the King’s Road in Chelsea at the Holiday Inn across the way. “If there was an earthquake, I’d be waiting outside for it to collapse,” he snaps. The ugliness of the modern world is a constant assault on Blahnik’s sensibilities, everything from the “cheap, suburban” interior of his offices (“I can’t change anything,” he grouses) to the bunch of lilies, newly purchased from a local supermarket, in the reception area. “I’m an old bag—I like old things,” he says by way of excuse. He’s his mother’s son: At the age of 97, with cataracts, she was still sharp enough to notice on the television that ex-Prime Minister Gordon Brown’s fingernails were chewed and dirty. “Can’t anyone in England tell that man to have a manicure?” she wailed.

Still, mounted on a stand in that same reception area is a shoe from the new collection. It is as fine as a fairy’s foot, but it’s cut from black leather and it restrains the dorsal with corset-laced metal plates. It would make Baron von Sacher-Masoch’s pulse race. And then it makes perfect sense that, as much as Blahnik swoons to Norma Shearer in Marie Antoinette (1938), he is crazy for Claire Danes in Homeland. If he’s an old bag, he’s a modern old bag, which is why he is full of praise for new shoe stars such as Nicholas Kirkwood, Charlotte Olympia, and Benoît Méléard. They are Manolo’s children. Blahnik himself turned 70 in November, but he dodges time as efficiently as he eludes the efforts of cold, hard print to capture the cadence and cascade of his speech. You’ll just have to take on faith the crescendos, the diminuendos, the trills, the over-egging, the effortless syntactical glides from hither to yon. And just pray that Manolo will one day take his show on the road.

TIM BLANKS: I have to say, you look better than you did the last time I saw you.

MANOLO BLAHNIK: Well, last time, I had this, what do you call it? What is it called, this, this thing here? [Blahnik’s hands circle over the right side of his torso] Forget about it. I forget about the diseases that I have. I don’t want to know. But anyway, so I have this thing here, and when I went to this award at the Savoy, I was 40 degrees [centigrade] in temperature, and I said to people, “Please forgive me that I’m out of it.” And I was waiting to be photographed. And I almost fainted on that girl, the tiny woman from France, no, from Mexico . . . Salma Hayek. But she’s a sweet girl, beautiful. I love that. This is what I really love: Where are those girls? I was looking the other day, Lara Flynn Boyle in Twin Peaks and that other girl Sherilyn Fenn—they’re old-school girls like Elizabeth Taylor, and I think that’s so fabulous. David Lynch is démodé now, if you look at his films. I looked at them the other weekend. I said, “I’m going to stay in bed, I can’t take anymore.” And so I watched the whole series of Twin Peaks. I was in heaven. And I realized how bad it is.

BLANKS: How bad?

BLAHNIK: How old-fashioned. If you think that the next day, I watched L’eclisse [1962] with Alain Delon and Monica Vitti. Changed my world. What a glamorous and modern film. This is what a genius is—the thing of a genius. The dresses, the tiny heels, the Cardin look, the boys dressed up as Italian gigolos—it was divine, very modern. Antonioni, I loved and I realized: how modern. And, you know, this is the mark of somebody. Then I saw these girls like Sherilyn Fenn and Lara Flynn Boyle that should be working now instead of these anonymous girls. They’re all the same. I don’t even know Amanda Seyfried or whatever—they’re all the same! I try to remember—the only one I remember is Julia Roberts because she’s particular. Anne Hathaway . . . Pretty? Yes. Wonderful actress? Yes. But, I mean, I don’t even remember her. What is it about her?

BLANKS: She was very good as Cat Woman in The Dark Knight Rises.

BLAHNIK: As Cat Woman, yes, and I’m not saying she’s not beautiful or a great actress. I just don’t remember her.

BLANKS: But remember how Hollywood went in those cycles in the ’20s, ’30s, and ’40s. There’d be a wave of very strong actresses, and then—

BLAHNIK: [interrupts] Nobody, nobody . . . just boring. Well, you did have Jeanette MacDonald. [both laugh] Back again to this madness. I went last year to the University of Savannah in Georgia. They invited me to talk with this man from the Sunday New York Times, and there was this huge, marvelous theater, and then I saw the marquee said, “Norma Shearer and Manolo Blahnik tonight!” And I almost fainted, and the woman from the television said, “Do you like Norma Shearer?” and I said, “I adore her! Are you kidding?” And it was absolutely the most fabulous talk with millions of university kids, all them 17, 19—I don’t even know how they knew me, but no matter. Then they had a small exhibition of the things I’ve done in the past—but anyway, what was I saying about the movie stars? My god, they used to be incredible.

BLANKS: Have you seen Amour?

BLAHNIK: I’m going to, because I adore Jean-Louis Trintignant—even at 100 years old he’s fabulous. And Emmanuelle Riva. Hiroshima Mon Amour [1959], I’ve seen it at least three million times.

BLANKS: I thought it was amazing that they were prepared to reveal themselves to such a degree for Amour.

BLAHNIK: [interrupts fiercely] Why not? I mean, they’re actors and they still have that desire until they drop. Even tomorrow you ask, I don’t know, Kirk Douglas? You ask him to do a part in a movie, and he jumps. This is the actor’s life.

I have always been an admirer of Manolo. Nobody else can create such elegance in a shoe, and watching him sketch and work and help bring my ideas to life has been inspiring.Victoria Beckham

BLANKS: Is that like an artist’s passion?

BLAHNIK: Passion is passion. It’s a sort of madness and possession of what you do or what you think. This is the difference of life: passion and commerce, which most of the people know as “P.C.” But people have just got “C” now instead of “P.” The only people that come to my mind in the last two years are Lee McQueen and John Galliano. Truly, truly . . . How do I say? Full of ideas. Full of the smell. They just had this incredible passion for what they did. Alas, passion is conducive to certain other things because when you have too much passion and you have too much work, you possibly end up having black holes. The danger is too much passion.

BLANKS: Can we go back? I want to know what made you sit down one day and watch all of Twin Peaks?

BLAHNIK: Because I don’t know what it was. I saw it originally, a hundred years ago. It still works to a certain degree now, for me, but at the time it was really wonderful. And this is the reason I watched it again. Because the film is pure Americana.

BLANKS: It’s so macabre.

BLAHNIK: I don’t like this thin Laura Palmer face all the time, made up like Mary Quant with the gray. It works the first time. The second time, you laugh. You can see the tricks. I like that part of Lynch where he really has this Elizabeth Taylor kind of fixation with the makeup and everything, and he tells the girls, “Do that.” But I really think when you compare these things with an old movie, L’Avventura [1960]. I watched three the other day—you know, I don’t sleep very much, so I watched L’Eclisse, La Notte [1961], L’Avventura. It’s really the most exquisite thing I’ve seen in years.

BLANKS: And what are you relating to when you watch these films?

BLAHNIK: I’m relating to a period that doesn’t exist anymore, but I knew it when I was a boy. I remember the women, how they dressed, how they behaved, what was important to them at the time. Like Lee Marvin and Gloria Grahame in The Big Heat [1953].

BLANKS: Talking about passion. Is it something you recognize in yourself?

BLAHNIK: I don’t even think about the word. But I do have certain things where I just go, “Aaaaahhh,” irritatingly boring and insistent because I want it to look that way and I can do it—I don’t even know if you’d call it passion or obsession. Obsession, possibly, but I really love what I do. It’s the only thing I really enjoy—so fresh, even now that I’m doing the new sampling. I’m dying to go to the factory, which is like nobody’s idea of fun. But it’s mine.

BLANKS: So you’ve carved all the shoe lasts?

BLAHNIK: I’m doing that now. But this is for 2014, Summer. You know, you have to work that way in shoes. I mean, you’re still doing couture for Summer 2013. God, I love that. Isn’t that great?

BLANKS: You seem much more mellow than when I interviewed you on your 60th birthday. You seemed to have more angst then.

BLAHNIK: Possibly, yes. But it depends on the days, you know? Maybe one day you pick me up with such a problem or a lot of pressure here. I don’t even know. I don’t think about myself very much.

BLANKS: Don’t you think it’s interesting what’s happened with your world? The way Grace Coddington has her autobiography, and Peter Schlesinger had his book of photographs.

BLAHNIK: And Eric [Boman] is going to have another book.

BLANKS: What do you think people’s fascination is with that period in the ’70s?

BLAHNIK: I was trying to think about that. Peter Hinwood found all these old pictures—Polaroids—and when I saw them, I just didn’t believe that the person in them was connected with me. I was in a hotel room with one of those front-and-back mirrors, and I thought, Who the hell is that? I used to be thin as a rake. I used to have the nice-shaped pecs. It’s sad. No, it’s not sad, it’s the reality, and I’ve accepted this now. You realize how much fun we did have, with no money at all. We’d stay in peoples’ homes in Tangiers. When you’re young, you invite yourself. Well, not me. I’d always stay at the Atlas Hotel or wherever.

BLANKS: But do you think the fascination is because it seems so happy?

BLAHNIK: Spontaneous. With that particular period, something was fuelled by what was happening. There used to be parties in London every night and some kind of excitement in the streets. You’d see extraordinary-looking people around in the ’70s. It was so exciting! You’d have mad people, like Gerlinde [Kostiff] riding around on her bicycle with a huge hat. Everybody was doing things. I don’t have any bad memories of that period. It was a different social structure. I’d go to [David] Bailey’s for dinner at 10:30. There were always girls there and a house full of . . . I don’t know, anybody. Cecil Beaton, Diana Cooper . . . And there I am sitting down with these creatures of the 20th century, and it was normal to us. I wasn’t even impressed. I mean, I was a young man, and this is the kind of London it was, but so many people are just not here anymore. Not even Tina [Chow], who was to me absolutely the most important girl of the time. Tina was absolutely the chicest thing, the way she kept herself, the way she moved. You’re born like that—you cannot acquire it. All those upper-class girls, people like Catherine Tennant, they used to be there in Chelsea, sitting on the couch. Now Chelsea is full of Russians . . . Or I don’t even know who they are.

BLANKS: I bet that when Grace was young, she never imagined she’d end up writing a book about it all.

BLAHNIK: Neither did I. I mean, all those stupid books of pictures and drawings of mine.

BLANKS: But it is hard to resist the feeling that it was some kind of golden age.

It was one of the most exciting moments when Manolo agreed to collaborate on our first season. I actually pulled a few shapes from his archive that he was able to reintroduce for that collection.Alexander Wang

BLAHNIK: You know, I don’t have this kind of perception. I’m not very nostalgic, you see. I just don’t think anybody has that kind of thing anymore. By culture, by breeding, by whatever, it’s not there. The kids today-what the hell are they going to be? I like young people—yes, I do. But when I talk to people at the schools, and they say, “I saw you on the Twit,” I don’t even know what they are talking about.

BLANKS: What do you think are the most important qualities are for a person to have?

BLAHNIK: Curiosity is a must. But I also . . . [sighs extravagantly] I’m loyal to my thoughts, to my friends. This is what I really like the best. Loyalty. Sounds goody-goody. Maybe that’s not the one you wanted.

BLANKS: No, I think loyalty is important-but I think curiosity is more important. [laughs]

BLAHNIK: Curiosity is much more exciting, yes.

BLANKS: In that conversation we had 10 years ago, we were talking about your relationship with the women whose shoes you design. I’d said that I thought that empathy would be important, and you said unapproachability was more significant. Has that changed in the last 10 years?

BLAHNIK: No, no, no, no. I know much more than I did, but I don’t think I’ve changed very much in any way.

BLANKS: And have the women changed?

BLAHNIK: Well, that kind of woman who used to be there at the time is not here any longer. In 10 years, people disappear. But I fantasize still about those kinds of women, and that kind of life that doesn’t really exist any longer. For instance, I went to Rome the other day, and I was invited to a huge palazzo, and I was observing the women there. You can still see women that have been through that kind of life and behavior. I’m a great observer of delicate situations and women. I really like that bygone type of movement, and for a long time I had been looking for it. They were old ladies, maybe, and not so old ladies, but they were beautiful. The way they moved, and talked, the intonations and things. It was beautiful.

BLANKS: And what can you give women like that?

BLAHNIK: Oh, what can I give them? Maybe answer the questions, or whatever it is. The conversation just happens. It’s not forced. I was at a table with a woman saying, “Oh, Manolo, tell me, what are the colors?” This is when I really find empathy with a woman, when you have this incredible contact with her for no reason-just simply because she’s giving you this movement or conversation or what have you. I don’t know—she provokes you.

BLANKS: And do you think that’s because of the intimacy of what you do?

BLAHNIK: Even before I did what I do, I guess I used to have that kind of thing with women. I’ve always had it with not-young women. I don’t like very young women very much. Never did. I mean, I do, yes. I still do. But, I mean, not that young any longer. I think Lucy Ferry, now Birley, is absolutely beautiful. She’s a modern girl, but she moves beautifully. Amanda [Harlech] moves beautifully when she’s not working. All those English leftover society girls . . .

BLANKS: But then, you’re also working with somebody like Victoria Beckham.

BLAHNIK: But this is another story. This is a woman who could do whatever she wanted to do, have a house in Majorca, raise children, be a footballer’s wife. But she’s not at all like that. I thought she was going to be one of those pop girls, but she’s absolutely the complete opposite. She’s a working girl. She knows what she wants. And when she doesn’t know, she really prepares herself. I love this working type of women. And she’s a girl from—I don’t even know where she’s from.

BLANKS: Essex.

BLAHNIK: I never watched those Spice Girls. I didn’t enjoy that at all. So I didn’t know her well. But she came out with this pretty boy, got married, and the boy got more tattoos and more tattoos. And then I met her a few times, and we started work, and something happened. You know, she wanted it. She loves what she’s doing.

BLANKS: What do you learn from an experience like that?

BLAHNIK: Well, you learn to accommodate. She wants that? I’ll give her that. I only saw one collection of hers, and I thought it was very much like Pierre Cardin or Marcel Rochas dresses. She’s thought about it, and she knows what she wants. And people buy it, so that means she works. She has this incredible will power to do something that she likes to do. And I love that. I respect that.

BLANKS: Do you identify with that?

BLAHNIK: I really connect with her desire to do something that she wants to do. Of the girls we’ve been talking about, she’s one of the few that has this incredible sort of “I want to do it, and I want to do it well.”

BLANKS: How has your own attitude to what you do changed?

BLAHNIK: Unfortunately, it hasn’t.

BLANKS: Did you ever feel like stopping?

I remember going crazy at his shop in 1985, when I began to work at Vogue, and buying his ‘Caldo’ in every single color . . . I began to wear them every day with a different color on each foot. In 1991, Manolo created a mule with pearls and crystal for me and called it ‘The Cerf.’Carlyne CERF de DUDZEELE

BLAHNIK: Oh, no, no! When I was out of favor and people didn’t want that type of boot, flats, or high heels with the elegant, dainty things, it gave me much more energy. I’m totally twisted. Instead of, “Oh god, I don’t have platforms—they won’t like me,” I was much more, “I’m doing what I’m doing, and if you don’t want to buy it, then don’t buy, but that’s just what I’m gonna do.” It gave me strength. It worked for me. I’m going to do what I do, even more exaggerated. This is my attitude always. I don’t betray myself at all. I’m always kind of contradictory to what people want and what’s selling. But maybe I should care now because I have two or three more outlets. I have to be more adaptable color-wise to what people want. It’s usually just black and pink, and that’s it.

BLANKS: Are you pleased that there seem to be so many more shoe designers around now?

BLAHNIK: I’m glad. I like the new shoe designers. Not all of them—there are really bad ones too. But I go to the colleges with these kids for lectures, as an honorary professor or whatever, and this Chinese girl I like very much who I give the award to says to me, “You don’t know how much you inspired me to do shoes.” And I’m glad that I convey that kind of desire to people when they see my bloody shoes.

BLANKS: But when you’re in the Dubai Mall, for example, and you walk past your shop, it is inspiring. The shoes are like jewels.

BLAHNIK: Some of them, not all of them. You get two weeks after you do a shoe where you can test whether it’s good or not—if you’re going to like it in 20 years. Then I know that it’s going to be my shoe for a long time. That doesn’t happen very often, but it happens.

BLANKS: For some reason, I picture what you do as quite a solitary profession. Do you think you spend more time on your own than you used to? You say you’re loyal to your friends, but do you—

BLAHNIK: [interrupts] I’m loyal to my friends, but I have so few now, some in Madrid, some here, some there. I force myself to see people when they’re here. Or when I’m here. I don’t live in England that much now in the sense that I spend time in factories. I’m such a factory man now. This is really what I enjoy doing.

BLANKS: But do you think you are a solitary person?

BLAHNIK: Indeed, I was. I am. Yes, I do enjoy my own company. I cannot imagine anybody entertaining me more than I do. If it sounds selfish, I don’t care. I made it a religion almost. Isn’t it awful to say that? The only way I can cope with me and my environment is to have this kind of wall around me. I’m exhausting myself. I am exhausting myself. [a huge oof of exasperation]

BLANKS: But it is the fairy tale of the shoemaker. Late at night, you walk through the village, you see the candle, and there’s the shoemaker making shoes.

BLAHNIK: I wish I was making shoes instead of reading or watching movies, which is what I do in my free time. But while I’m at the factory, I do that, yes.

BLANKS: It’s a very elegant image.

I was in a hotel room with one of those front-and-back mirrors, and I thought, ‘Who the hell is that?’ I used to be thin as a rake. I used to have the nice-shaped pecs. It’s sad . . . No, it’s not sad, it’s the reality, and I’ve accepted this now.Manolo Blahnik

BLAHNIK: Maybe for you. I haven’t thought about it. [both laugh]

BLANKS: Once, I asked you where you belong, and you said, “It’s not good for one’s state of mind to belong somewhere.”

BLAHNIK: I don’t belong anywhere. I don’t think it’s good for you when you say, “Ah, I’m French.” What a disaster if I was thinking that way. Oh, I’m Spanish—what a horrible thing. I never thought about belonging to some group or other. I guess I’m like a Gypsy. I don’t think I live the Gypsy life, but I fit anywhere. In America, I find it difficult, but anywhere in Europe, I’ll be okay. If I belong to somewhere, I belong to here.

BLANKS: You’ve also said that you’ve never been in fashion.

BLAHNIK: In fashion? I don’t think so. I’ve been in an unreal world. I never feel that I just do fashion, really. I just do pretty things. Pretty objects.

BLANKS: Do you think what you do is important?

BLAHNIK: No, I don’t think so. It’s important to me because it gives me incredible joy, and joy to the women who buy the shoes, because I guess that I touched them through doing pretty things. I touched the psyche.

BLANKS: And there is that obligation to bring beauty into the world.

BLAHNIK: I think that it is important. I always repeat the same thing: as long as you don’t bore people. Boring people is like death to me. That’s why I really like vivacious people, or people who just say whatever they want to say.

When I was out of favor and people didn’t want that type of boot, flats, or high heels with the elegant, dainty things, it gave me much more energy. I was much more ‘I’m doing what I’m doing, and if you don’t want to buy it, then don’t buy.’Manolo Blahnik

BLANKS: Do you think that you’ve been able to satisfy all your ambition-by designing shoes?

BLAHNIK: I have no idea of myself being ambitious. You know what I would really like to have done? I would’ve loved to be somebody who builds walls. Not walls with bricks, but beautiful things with engravings, murals, frescos, and wonderful Corinthian columns. I would have been a mason. Not now, because I’ve got a bad back. But this is one of the things that frustrates me—that I am not able to do it anymore. I love stones. And I love making shapes of stones.

BLANKS: Shoe design. Masonry. They are two forms of architecture.

BLAHNIK: Maybe, but I don’t like architects very much, unless you have extraordinary visions, and shapes to give to people. Bernini? Michelangelo? Nowadays, I don’t know. Maybe Zaha [Hadid].

BLANKS: You would never say that what you do is a dying art, though, would you?

BLAHNIK: No, because there will always be someone who really likes what I do. I don’t think it’s a dying art because I’ll still have some ladies, 80 years old, 70 years old. Maybe it’s a dying art if you compare it to young people wanting to do it, but maybe young designers will bring some new kind of technique, like doing something in one piece of rubber. But that’s not what I’m talking about. I’m talking about the traditional way of doing shoes. And no, I don’t think it’s a dying art. There’s always somebody who wants that kind of shoe going on. I do.

TIM BLANKS IS EDITOR AT LARGE AT STYLE.COM AND FREQUENT CONTRIBUTOR TO INTERVIEW.