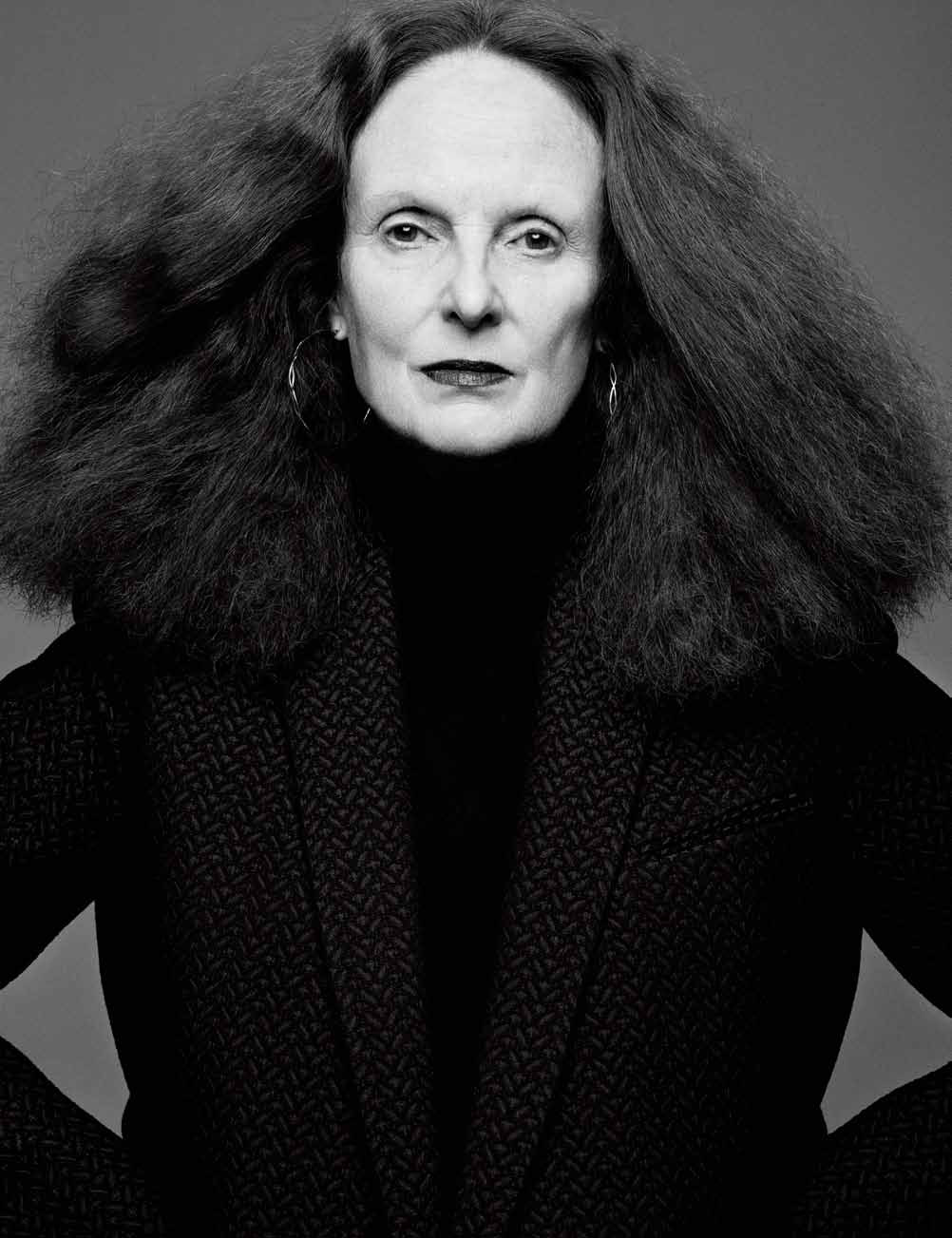

Grace Coddington

some peopLe were surprised at what they saw in The SepTember ISSue because i think i had a reputation before for being sort of coLd and austere . . . but then that movie came aLong and peopLe saw that i was very passionate’-Grace Coddington

Grace Coddington has been in and around fashion for more than five decades, first as a successful model in the nascently swinging days of 1960s London, and later as a stylist and fashion editor for both British and American Vogue. But these days, Coddington is more often recognized as a kind of romantic heroine. This is due, in large part, to her role in R.J. Cutler’s 2009 documentary The September Issue, which offered a rarified window into the innermost sanctums of Vogue as the magazine’s staff dreamed up, arranged, plotted, coordinated, schemed, scurried, stumbled, and ultimately triumphed in pulling together the 840-page September 2007 edition—to that point, the largest issue in Vogue history. (It has since been eclipsed by the September 2012 issue, which clocked in at 916 pages.) From it all emerged Coddington, Vogue’s creative director, whose Pre-Raphaelite hair and vividly imaginative ideas find her chafing against the cool sobriety and pragmatism of a world increasingly not conducive to the kind of dreaming that often fuels fashion at its brightest.

Coddington, though, isn’t a throwback or an anachronism. In fact, she’s quite the opposite: a radical individualist whose appreciation for both fashion and beauty extends far beyond pure aesthetics, and who, as a stylist and image-maker, consistently captures what’s in the air at any given moment in surprising ways. Her work embodies the spirit of someone who is in love with the idea of falling in love—whether that ultimately means eternal bliss or soul-crushing heartbreak—and infuses fairytale and fantasy with a kind of unerring naturalism. Many of the pictures she has had a hand in making with photographers such as Arthur Elgort, Steven Klein, Annie Leibovitz, Peter Lindbergh, Steven Meisel, Irving Penn, Mario Testino, and Bruce Weber are among the most iconic to have appeared in American Vogue over the past quarter century and, as much as anything, have come to define the magazine’s sense and sensibility when it comes to fashion.

As its title suggests, Coddington’s new book, Grace: A Memoir, written with Michael Roberts, is an unpretentious chronicle of her life in full: her childhood in Anglesey, Wales, and her early days as a model in London; the car accident that sidelined her for two years, and her decision to abandon modeling for a career as a stylist and editor; her marriages to restaurateur Michael Chow and photographer Willie Christie; her move to New York in the mid-’80s to be with her current partner of nearly three decades, the hairstylist Didier Malige; her singular—and, at times, complicated—relationship with Vogue editor in chief Wintour; and her famous love of cats. But when it comes to the remarkable body of work she has created, first under Beatrix Miller at British Vogue and later with Wintour at American Vogue, Coddington avoids indulging in too much analysis. Instead, she does what she does best: riff and roll on what was, what is, and what can be, with passion, humor, and an unending sense of possibility.

Designer Nicolas Ghesquière recently spoke with Coddington, now 71, in Paris, where they discussed her newfound celebrity, her decision to write a memoir, and the long, winding road of her life—both in and out of fashion.

NICOLAS GHESQUIÈRE: You’ve spent much of your career working in the background and avoiding the spotlight, so why did you decide to write your memoir now? Why was this the right time?

GRACE CODDINGTON: Well, I guess I’m kind of in denial. Before The September Issue, people were saying, “You know, when this movie comes out, everyone is going to be asking for your autograph and people are going to start stopping you on the street.” But I was like, “Absolutely not. My life will not change.” But it did—dramatically—in terms of me being recognized, because I was completely not recognized before. People stopping you in the street, though, is very different from being hounded by the press, which is the kind of attention that celebrities get, and I’m probably too old for that kind of thing to happen anyway. I think it happens more when you’re dating all sorts of different very handsome actors or something. They want gossip and scandal, and they know they’re not going to get it from me because I’m too old to be scandalous. Of course, they could read the book—although it’s not really a scandalous book.

GHESQUIÈRE: So why did you decide to do the book?

CODDINGTON: Why did I decide to do it? I think I was somewhat pushed into it—but not by Anna [Wintour] this time, like with the movie—but just because after the movie, I got many, many offers to do different things.

GHESQUIÈRE: The movie was part of it then.

CODDINGTON: The movie and my age. I mean, if you’re going to do a memoir, then it’s sort of at this age—in your late sixties or seventies—that you do it. I don’t understand people who do memoirs when they’re 20. I think most people need a little more time than 20 years to become the person they are. In fact, that process of becoming who you are is still ongoing when you get older, where you go, “Let’s see where my next 10 years is going to take me.” So after the movie, I got many offers to do things like this book, and I kept saying, “I’m not going to do that. It’s too private.” But I think people wanting me to do it kind of persuaded me to do it. I also think some people were surprised at what they saw in The September Issue because I think I had a reputation before for being sort of cold and austere. You know, there was me and there was Liz Tilberis, and Liz was always the friendly one who chatted with everyone, and I was the one who didn’t chat with anyone. But then that movie came along and people saw that I was very passionate. There’s one particular scene in the movie that everybody talks to me about.

GHESQUIÈRE: The scene at Versailles?

CODDINGTON: Yes. I think it was probably that moment in the movie that brought me to the eyes of people.

GHESQUIÈRE: What’s so great about that scene, I think, is that it shows the sensitive and emotional side of fashion—and of who you are—as well as all of the romanticism and humor that goes into how you approach your work.

CODDINGTON: Well, I hope the humor comes through in the book. I don’t want to make myself into a historian or someone too super-serious. I mean, I take my job very seriously. But I think you have to laugh in life.

GHESQUIÈRE: There is something you say in that Versailles scene about being a romantic and how there is something about how you look at the world that is from another time.

CODDINGTON: I think what I said is that I should have been born in another century. I am kind of too old-fashioned for this crazy fashion business, but when I said that, I wasn’t referring to fashion as much as to the fact that everything has become about computers and blogs and all those things that I can’t come to grips with. Half of me doesn’t want to come to grips with them. I think those kinds of things have changed the world so that everybody now multipurposes and multitasks, which makes it hard for people to focus on what they’re doing and where they are in the moment. I think that’s a sad loss in life. I think you have to live a little bit more in the moment and appreciate and see. It is what I’ve always done in my life—just look at where I am. That’s why I love going on the subway in the morning. There are so many wonderful people on the subway. I’m often sad that I only live three stops away from the office in Times Square, because I’m usually just working out who that crazy person is in the corner when I have to get off.

GHESQUIÈRE: Do you ever forget your stop when you’re doing that?

CODDINGTON: Oh, I have done that—and then I’m panicked and don’t know how to get back again because I have no sense of direction. But what was also amazing about that day that the scene in the movie captures is that it wasn’t just a beautiful blue sky and pretty flowers—it was a very gray day and there was rain in the air. My hair was blowing all over my face . . . But that’s what made it kind of great. I don’t know if you liked this movie, because I think a lot of French people hated it, but it reminded me of Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette [2006], which I loved. As I was looking out over the gardens, I was thinking about how that movie brought all those historical characters to life, with how they were dressed and running through the topiary and stuff. It brought those gardens to life.

i’m often sad that i onLy Live three stops away from the office in times square, because i’m usuaLLy just working out who that crazy person is in the corner when i have to get off.’ -Grace Coddington

GHESQUIÈRE: I’ve always found you to be in completely good spirits and happy and smiley on set. Where does that energy come from? You’re never blasé.

CODDINGTON: I don’t think I’m ever blasé. Sometimes I’m a little desperate when I feel that what we’re going for is not happening. But you have to be positive, even if you have a nasty, nagging feeling in the back of your head that something is wrong. There are always moments, though, you know? For example, when you and I were doing that shoot with Annie [Leibovitz], and she suddenly said to me, “This dress—the ruffles are on the wrong side. Just put it on back-to-front.” I don’t think you were in the room at the time, but I panicked.

GHESQUIÈRE: I remember.

CODDINGTON: I came to you afterwards because you didn’t see what happened when she asked me to do that, but the blood drained from my face. I was like, “I don’t know Nicolas terribly well, and if she insists that I put this dress on back-to-front, then I’m going home.” [Ghesquière laughs] So I’d already worked that one out with her—that wasn’t going to happen. But then she said, “Well, you’ve just got to put the ruffles on the other side.” But it was an incredibly complicated dress, and I looked at it and thought, “That’s not going to happen.” You were the one, though, who was totally amazing, because there was not even a flicker of anger or of “How dare you expect me to do this to my dress.” You said, “Sure, we’ll try,” which was an amazing answer, because there are a lot of designers who would not be so tolerant of that—even with Annie, who is a great photographer. It was a great moment for me in fashion, because if you can do that, then anything is possible.

GHESQUIÈRE: We basically redid the dress in 45 minutes. I think it was in that moment that we became friends. We broke the ice. But I think this energy and enthusiasm that you bring to your work is what has helped you amass the incredible list of photographers with whom you’ve worked. How have you approached your relationships with photographers? I’m sure that some photographers have come to you over the years, but were there others who you were craving to work with?

CODDINGTON: Well, yes—particularly the big ones. I mean, I always wanted to work with Irving Penn. The story of how I met him is in the book, but I thought I was going to run into him at British Vogue. I knew he was there. So I hung around the studios, and he was photographing flowers at the time, roses. I didn’t know what he looked like, so I didn’t really know what I was looking for, but I thought I’d run into him in the corridors. I’d worked with Norman Parkinson, who was such a character, but most of the photographers I’d met up until then were people like David Bailey—very groovy, in jeans. So I was standing around hoping to meet Irving Penn, and a man walked by in plain pants and a plain shirt, and I remember someone said to me, “That man who just walked by—that was Irving Penn.” But he didn’t look like what people thought photographers looked like, so I missed him. Eventually I got to meet Penn through Calvin Klein—the first time I worked with him was on one of Calvin’s ads. And then I worked with Penn quite a lot in the beginning at American Vogue. I also always wanted to work with Richard Avedon, but that wasn’t to be. He didn’t work for British Vogue, and by the time I got to American Vogue, he didn’t work for them either. But I always wanted to work with Guy Bourdin, and I worked with him a teeny bit as a model and later as an editor. Helmut Newton I worked with as a model and as an editor. So I guess I’ve worked with most of the other ones that I wanted to work with.

GHESQUIÈRE: You talk in the book about your childhood. You grew up on a small island in Wales, right?

CODDINGTON: Yep.

GHESQUIÈRE: It is said that your first interaction with fashion as a teenager was the copy of Vogue you received in the mail. What did you see in those pages that caught your imagination? Your parents ran a hotel. Were there any women that you saw there who fascinated you?

CODDINGTON: Well, the hotel was a little family hotel on an island off an island in a place called Trearddur Bay. I don’t know what it’s like now because I haven’t been back there since my mother died, which is quite a while ago. But back then there was nowhere to wear smart clothes there. In the winter, there were hardly any people. It was completely deserted and windswept with storms and waves crashing over the roads. Because the hotel was very close to the sea, it was closed all the way through the winter months, pretty much, except for the odd weekend because it was connected to a boy’s boarding school of sorts, so parents and other people would visit. But I didn’t have any role models there. It sounds so clichéd to say and like I’m doing a campaign for the magazine, but for me, in terms of fashion, it all came through Vogue. It was first the photographs that were appealing to me—probably more than the clothes. But I thought it was kind of a wonderful world. I think I probably imagined it was a very easy life—and a luxurious life—to be a model, which, of course, it’s not.

GHESQUIÈRE: So how did you get to modeling?

CODDINGTON: You didn’t read that chapter? [Ghesquière laughs] Well, you know, people said, “You should be a model,” because I was quite tall.

GHESQUIÈRE: And gorgeous.

CODDINGTON: No, not gorgeous at all. But I was tall compared to most English people. Compared to the Welsh people, I was really tall. But I just knew that I had to leave home and do something to make some money, so I applied to do a modeling course in London and went there. The modeling course was just a couple of hours a day, so I did that, then worked in the coffee bar the rest of the time. Then two things happened: The first was that one of the customers at the coffee bar said to me, “You know, I’m a good friend of Norman Parkinson’s. I think you should meet him.” The guy said he was a male model, but he was also a painter, very nice guy. There’s a funny story about him in the book—he’s called Tinker Patterson. Anyway, he said, “I’m going to set up an appointment for you at Parkinson’s.” I remembered Parkinson’s name from reading Vogue because he put himself in the pictures a lot. He was like a celebrity photographer.

GHESQUIÈRE: He was famous.

CODDINGTON: Yeah, so I kind of knew what he would look like and went off to see him. I remember trudging my book along to Parkinson’s, and he kind of looked me up and down and said, “Well, I think you’d be perfect for this job I’ve got on Saturday. It’s nude. Do you mind?”

GHESQUIÈRE: It’s your first job and you have to be nude.

CODDINGTON: Well, I didn’t really process that. I just heard, “I’ve got this job on Saturday. Will you do it?” So I said, “Absolutely.” Then suddenly, when I got home, I was like, “Oh, shit. It’s nude.” But I just figured that was the job. So off I went for my first job, a nude picture with Parkinson. But then, the second thing that happened was that another customer at the coffee bar said, “Vogue is having a model competition. Give me a picture of yourself. I’m going to send it in.” And I had a model card that the agency made me get—it’s the one in the book.

GHESQUIÈRE: Is it the picture with the sweater?

CODDINGTON: Yeah, with the big sweater and the straw hat and black leotards and my hair in bunches. I think I’m holding a rose.

GHESQUIÈRE: I love that picture.

CODDINGTON: So we sent that off, and somehow I ended up winning one of the sections of the competition.

GHESQUIÈRE: Did you do your look for that picture?

CODDINGTON: Of course I did.

GHESQUIÈRE: That was good styling, Grace.

CODDINGTON: You think? [laughs] I think it’s a big mohair sweater. I must say, I loved that sweater. I wore it for several years.

GHESQUIÈRE: I love that sweater, too—I think it still works. So you’re in London and it’s the 1960s, which must have been a very heady and glamorous time to live there, when high couture and fashion were very strong. Was it swinging London?

CODDINGTON: I mean, as it got into the 1960s, it was more swinging, but I arrived in 1959, so it wasn’t quite swinging yet.

GHESQUIÈRE: Nothing was swinging?

CODDINGTON: I think it was a little later that the swinging started. You know, what made it swing was when they invented the pill. That kind of changed everything.

GHESQUIÈRE: So how did it feel to go from starting out as a model to suddenly being in the middle of that inspiring cultural time of swinging London? Suddenly you were with the Rolling Stones . . .

CODDINGTON: Well, I can’t say I was with them, but I knew them. I also knew the Beatles and the great London photographers. I think I just hit at the right moment and met the right people. So I was part of that scene in a way.

GHESQUIÈRE: In the book, there is a picture of you with Vidal Sassoon.

CODDINGTON: That’s from 1964.

GHESQUIÈRE: It’s such an iconic image in terms of what people think about when they think of swinging London in the 1960s.

CODDINGTON: You know, I was lucky enough to be born with really good hair, so hairdressers always liked me because it’s strong and has the right kind of crown in the right place and things like that. I went through several hairdressers before I met Vidal. I think I first started going to him in 1960, so this was not the first cut—the five-point cut—which is the one that is kind of famous.

GHESQUIÈRE: How long did you keep the Vidal Sassoon cut?

CODDINGTON: Probably a couple of years. After that I had a cut where it was more one-sided. It started with the very even geometric five points because it was shaved up into the back of your neck. Then it went on into a one-sided cut where it was all over one eye.

anna always wants to know what you’re doing, even if you’re not with someone or doing something. she keeps her eye on you. she’s super-smart like that.’ -Grace Coddington

GHESQUIÈRE: I have a feeling that hair was very important to you from the beginning.

CODDINGTON: Still is. If I can’t have the right hair person for a shoot, I almost don’t want to do it.

GHESQUIÈRE: It’s a Grace Coddington trademark.

CODDINGTON: The red hair. That’s all they notice when they see me coming. My look is always quite specific because I don’t like halfway things. It’s even specific now. It’s black and red. I don’t think it’s predictable, but it’s very handy.

GHESQUIÈRE: Because you reflect that in your work so strongly. I can always see a Grace in your stories. Was it a natural move for you to go from being a model to becoming a fashion editor?

CODDINGTON: I think it was a fairly natural move. If you keep your eyes open when you’re modeling, you learn a lot about fashion and how shoots are done. I thought I knew it all—until I realized that I knew nothing at all about the responsibility of it. I just thought you would turn up at the studio with your favorite outfits and, hopefully, your favorite girl and photographer, and it just happened. Then I learned the hard way that you actually had to make it happen.

GHESQUIÈRE: Do you remember how you came to understand that? Was there a precise moment?

CODDINGTON: No. It was age . . . Again. [laughs] But there were a couple of things that happened. The first one is that I had a big car crash very early in my career as a model, so I had to stop modeling for a couple of years. Of course, I didn’t have any money at that time, so I started helping around the studio. Then, once my face healed, I went back to modeling. But by the time I went back, I was getting older and I looked around and people like Twiggy were coming along, and they were cute, and I wasn’t in so much demand. I don’t like to be in the going-down process—I think my motto should be, “Get out while you’re ahead.” So there was this remarkable woman who actually used to work for Saint Laurent [Lady Clare Rendleshan, who owned two YSL franchises in London], but at the time she worked on a magazine called Queen, which later became Harper’s & Queen. But she was an extraordinary editor who became a close friend of mine, and she’s the one who said to me, as only a friend can, “You’re too old. You should move on.” She said, “Why don’t you come work with me on Queen?” And I was still sort of struggling with the idea of stopping modeling, so I kept on modeling a bit. But then another editor that I worked with called Marit Allen, who was at British Vogue, called me up one day and said, “I think you should come work with us. You should have a meeting with Beatrix Miller,” who was then the editor. So I had lunch with Beatrix and she offered me a job. In a way, though, it was all about timing. I had just split up with my boyfriend, who I lived with half in Paris and half in London, and I’d gone back to live in London full-time, and I was just beginning to go out with Michael Chow. It was just before he opened his first restaurant, so he was very much in London, and this was a job that I saw as being more of an office job and more stationary, which would work for me and for the relationship. So I took the job.

GHESQUIÈRE: Did you start styling right away?

CODDINGTON: No, not right away. At one point they said, “What do you want to do?” And this is where I say that I thought it was so easy. It was a time of dressing when men and women dressed the same, so I had this unisex idea, which I should have done on two gorgeous-looking boy-girl people. But I didn’t. For some reason, I decided to do it on this painter Peter Blake and his wife, Jan, who was an artist, too. They were friends of mine through Michael Chow. But what I hadn’t taken into account is that Peter Blake is quite large, and I’m giving him and his wife these shirts, and they wanted to put them on over the clothes they already had on, so they just looked like a crumpled couple with lots of lumpy things under them. It was a terrible. But that was my first shoot.

GHESQUIÈRE: So how did you develop your way of styling and your signature as a stylist, which is so strong? How did that evolve?

CODDINGTON: That’s the thing: I don’t style. I think it took a long time to really develop what you call my style, which is not styling, because I don’t style. I very rarely push the sleeves up or turn the collar up or do all those things that stylist people do. I very rarely take your sweater and Marc Jacobs pants and put them together. I just like leaving things the way they are somehow.

GHESQUIÈRE: You are very respectful as an editor.

CODDINGTON: Yeah, because I really think that I can’t do better than you or than Marc. People probably think I’m either lazy or talentless because I don’t do anything to the clothes. I can tell you, there are a lot of people, even within my own building, who look at me and say, “Well, I actually do something with the clothes. I don’t just put the full design or look on.” But I’m like, “Okay. That’s your way. Fine by me. I just don’t think I’m better than the designer.” So I choose the thing that is already what I like.

GHESQUIÈRE: One thing that is often so remarkable about your stories is that they are so dreamlike. They’re very Baroque and generous, which is not exactly what’s happening in this moment in fashion.

CODDINGTON: Well, I like to think I can do that. I don’t know if I’m successful because I’m not one of those young people who are doing what’s happening in the moment.

GHESQUIÈRE: I don’t believe it’s a question of age.

CODDINGTON: Well, no. I’m being slightly sarcastic. But my automatic thing is to go very Baroque and romantic and soft and pretty. Your collections, for example, are very often not like that. But I have an appreciation for what you do, and it pisses me off that it doesn’t always fit into my story. And then Anna always pigeonholes me into some romantic pigeonhole—you know, with a lot of pigeons and rabbits or whatever. You try to get a Balenciaga dress in there and it’s hard. So I have to think it through and rationalize it until I can understand how it can get in there. I can’t give it to the photographer or the model to put it in place. I’ve got to help them see it there, too.

GHESQUIÈRE: How did you meet Anna? How and where and when?

CODDINGTON: I don’t remember when we met. I used to see her around all the time. She used to work for Harper’s & Queen in London.

GHESQUIÈRE: Did you see her at fashion shows?

CODDINGTON: Yeah. She’s a lot younger than me. But she was a cool-looking girl, and she used to hang out with other cool-looking girls. I think she probably hung out with Amanda Harlech and people like that. So yes, I used to see her around a lot, and some of our friends sort of crossed over. But I can’t remember any particular moment when I actually said, “How d’ya do? My name is Grace Coddington.” I knew her husband before . . . I guess I became friendly with them just before they were married. I knew them both individually, and then one day, David [Shaffer] said, “Oh, come and meet my new girlfriend,” and there was Anna. At that point, I think she’d just been offered the job as creative director at American Vogue.

GHESQUIÈRE: So you were in London at that time and Anna was going to move to America.

CODDINGTON: Anna was already living in America because, I think, she had gone there to work at New York magazine, which is where Alex Liberman [the late editorial director of Condé Nast and art director of Vogue] found her. But she worked on several magazines before that—including Harper’s Bazaar, I believe.

GHESQUIÈRE: So you met her in another context.

CODDINGTON: Yeah, she was an editor, then she was creative director, but we also had friends in common, like Joan Buck. I met Anna over at Joan’s house a few times. But she was never very chatty at that point. And she was always . . . I couldn’t see her because she always had so much hair in front of her face. [laughs]

it took a Long time to deveLop what you caLL my styLe, which is not styLing, because i don’t styLe …i just Like leaving things the way they are somehow.’ -Grace Coddington

GHESQUIÈRE: Tell me then about how you moved to America.

CODDINGTON: Well, I worked with Beatrix Miller for 18 years, but then she retired and Anna was given the job as editor of British Vogue. And that was a difficult period because suddenly this young, bright, snappy person—not snappy in a bad way, but very efficient, with a very different kind of point of view to mine—came in, and I was very used to just running things my way. Anyway, a new editor is always difficult to deal with on a magazine, and if you’ve been with one for nearly 20 years, then you start getting lazy. You get lulled into a false sense of security. But then Anna came in and woke everybody up, and it jolted me a great deal. I felt somewhat in the way. Also at around the same time I’d started coming to America to see all the American shows. I was one of the first European editors to go to all the New York shows. I saw Calvin Klein and thought Calvin was really interesting because nobody here was doing anything like what he was doing at all—it was very modern and slick. So I became friends with someone who worked in his studio called Zack Carr. The other thing was that, by this time, I was dating Didier [Malige, Coddington’s partner of nearly 30 years], and he lived in America. Everything to me at that point was saying, “Go to America,” so when Calvin offered me a job, I decided to go.

GHESQUIÈRE: So you moved for love . . .

CODDINGTON: Yes. He was going to take me a bit more seriously if I came to live in his city. Couldn’t ignore me. So I came and I worked for Calvin.

GHESQUIÈRE: For how long were you at Calvin?

CODDINGTON: Not very long. It was a year and a half. That was hard, too. I think I bit off a bit more than I could chew. At that point, my friend Zack Carr had left and gone off on his own, so I had a team of people I didn’t know and I didn’t know what they expected of me. So it wasn’t right. It was kind of awkward and I made some major mistakes there.

GHESQUIÈRE: But through that experience I’m sure you got to see the process of doing a collection and making clothes from another perspective.

CODDINGTON: Which was very interesting. I also saw it from an American point of view, which is very much about working with a team of people. But even though I embraced Calvin’s style, I’m sort of a chameleon really. If I see something out of the corner of my eye, I want to go in that direction. But if you work for a designer, you’ve got to stick with their aesthetic. You can’t suddenly turn a corner.

GHESQUIÈRE: You are turning on to a religion when you work for a brand like that with such a strong aesthetic and vision.

CODDINGTON: Oh, absolutely—from the tip of your toes to the top of your hair. But, again, it was a timing thing, because right at that moment, Anna was made editor of American Vogue. She had gone to work for House & Garden, but then I picked up Women’s Wear Daily one day and it said, “Anna Wintour is the new editor in chief of Vogue.” We’d always kept in touch—Anna always wants to know what you’re doing, even if you’re not with someone or doing something. She keeps her eye on you. She’s super-smart like that. So I called her up to say congratulations on the job, and I suddenly thought, Maybe what I should do is go to American Vogue. But I thought she’d never have me because I kind of left before. So I was saying, you know, “Congratulations on the job,” and I said half-joking, “You wouldn’t ever want me back, would you?” And she said, “Meet me for a drink at six o’clock.” So I said, “Okay,” and then she hung up as she does. [laughs] But I remember going for the drink, and just as I pulled up my chair, she said, “Start on Monday—I’m starting on Monday.” So I was like, “Fine. Thank you very much.” And the rest is history.

GHESQUIÈRE: Do you know if she was thinking about that before you called her?

CODDINGTON: I don’t know.

GHESQUIÈRE: Never asked?

CODDINGTON: I never asked. But I mean, Anna knows exactly what everyone is doing and thinking because everybody confides in her. Probably during one of our dinners I said something. But I also think that she wanted her team in there at Vogue. She wanted to change the magazine. She made that very evident.

GHESQUIÈRE: That’s my next question, actually. How did Anna go about remaking Vogue in the beginning? How was it set up?

CODDINGTON: Well, it was all Anna’s direction. She brought in Carlyne Cerf de Dudzeele and Jenny Capitain and all those girls. She brought them in when she was creative director, and then she left and went to British Vogue, and then came back again. But I didn’t set it up—she set it up. So I can’t really answer that.

GHESQUIÈRE: But you were there.

CODDINGTON: Well, we each had our own little areas that we were strong at. I think Carlyne was the key one there in the beginning. She had the loudest voice. She came from Elle, and her approach was very modern. It was quite bright and tough. She was Anna’s American Vogue. So for a while, I just tried to fit in. There was Carlyne and André [Leon Talley]. They were the directional ones. So I kind of went through it all and tried to do what I thought was the style of the new American Vogue. And that was okay. I don’t think I did it very well. But I’m quite patient. So you just kind of sit and bide your time until it’s your moment.

GHESQUIÈRE: I’m sure this is a difficult question to answer, but are there any shoots you’ve done at Vogue that you’re most proud of having done? What, for you, have been some of the brightest memories?

CODDINGTON: Well, I always say that my favorite is the “Alice in Wonderland” shoot that I did with Annie [December 2003]. It was tough, but it was probably one of the most rewarding shoots I’ve gotten to do and certainly one of the most interesting. It’s amazing to work with someone like Annie, who is an intellectual. She’s not a fashion person, but intellectually, she’s very rich. So that was a defining one for me. And then another defining one is a shoot that I did with Bruce [Weber] for British Vogue inspired by Edward Weston and his daybooks. After I did it, Bruce made this little scrapbook for me—in the good old days when everybody had time to do things like that. It was made from real prints stuck into a scrapbook with writing all around them, and he taped them down with black tape. It’s one of my most treasured possessions. So I photographed the scrapbook and put those pictures in the book. The book is full of treasures from my life.

GHESQUIÈRE: What about Steven Meisel?

CODDINGTON: I’ve done a lot of pictures with Steven—and a lot that I love. He’s extraordinary because of his knowledge of fashion. Other people—like Annie, for example—have a different kind of cultural knowledge. But Steven has an incredible knowledge of fashion. He knows much more about it than I do. So to work with someone like Steven who has his history of making pictures—it’s mindboggling. I don’t work with him enough now. I miss him, actually.

GHESQUIÈRE: In the book there are also tremendous photographs that you’ve done with Arthur Elgort.

CODDINGTON: I have a great history with him. Arthur and I are kind of like an old married couple. We have lots of laughs. I’ll find him a girl that will intrigue him, and I try to think of a funny story we can do. He’s always up for traveling to the other end of the world and never complains about jet lag like I do. He also never puts the camera down, so he can record everything—he never misses the picture. In fact, I think it frustrates him that nowadays I come with a team, because he remembers, as do I, when you would travel and your team would be four people, which meant that you were very mobile and could go anywhere. But you can’t do that now because there are so many people involved. You’re also plugged into digital, which means you cannot move the camera, which I find frustrating.

GHESQUIÈRE: With one kind of freedom, you lose another kind of freedom.

CODDINGTON: Oh, totally—and I miss that freedom so much.

GHESQUIÈRE: Before we go, I wanted to talk to you about your cats. How long have you been a cat lover?

CODDINGTON: I think I’ve probably always been a cat lover. My parents didn’t have cats—they had dogs—so I didn’t own a cat until later. I mean, I love all kinds of animals, but I just focus on one and it’s cats. I find them very human, actually. They can sense your mood. It’s extraordinary. I had one early attempt that went terribly wrong because I was away too much and they got very neurotic. In the end, I had to give them away. So I didn’t attempt to own cats again until I got married the second time. The first time, I couldn’t have cats because Michael Chow is allergic. That was tough. But then my second husband and I both loved cats, so I got cats. Their names were Brian and Stanley.

GHESQUIÈRE: So today you have two cats?

CODDINGTON: Today I have Pumpkin and Bart, who are the latest in a long line of cats. I don’t think there’s ever been a period when I haven’t had cats since Brian and Stanley, which is quite a long time—30 years or something. But I always have to have a girl cat so she can wear clothes in my drawings. I don’t want to put dresses on the boys.