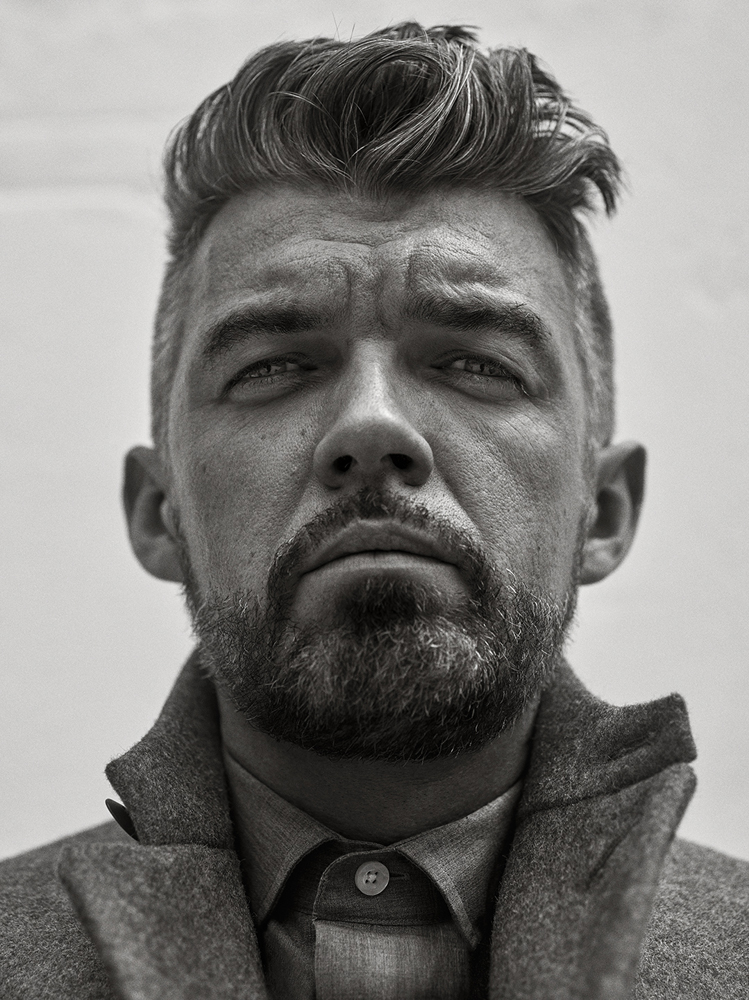

Nick Laird

Several of today’s finest young novelists moonlight as poets. Chief among them is Nick Laird, the 41-year-old writer whose last book of poetry, 2013’s Go Giants, was such a deliriously potent blend of hilarity and sorrow that you could actually spot commuters reading it on the subway. Laird has the rare ability to mate tragedy and comedy in a single line without making either side feel cheap for it. And it’s that same contagious wit, displayed so mightily in his poems, that enlivens his fiction. He has written three novels, all of them very funny right up until the moment your heart explodes. His third, Modern Gods (Viking), returns Laird to the familiar terrain of his Northern Irish roots. (Like his wife, the author Zadie Smith, Laird seems haunted by the stories and characters of his childhood turf.) There, in Ulster, a family gathers for a wedding that threatens to destroy the sanity of one sister, before another sister flies to an island called New Ulster, off the coast of Papua New Guinea, to investigate a new religious movement based on the phenomenon of cargo cults. Laird deftly invents a religion run by an oddball messianic leader (with a son in a Britney Spears T-shirt) and describes the balletic, bullet-by-bullet horror of a terrorist attack, all the while delivering beautiful truths. (“It happened like this. You were fine you were fine you were fine, and then you fell apart.”) This past April, Laird spoke by phone to his friend, the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Michael Chabon, about cults, critics, and the madness of metaphor. —Christopher Bollen

NICK LAIRD: I just finished your new book, Moonglow, and I loved it. I was struck all over again by how good you are with metaphors. I’ve never read your poetry, but I know you have written some.

MICHAEL CHABON: I mean, I used to in college.

LAIRD: Ayelet [Waldman, Chabon’s wife] told me you write poetry.

CHABON: Only for her. I wrote one poem on our 10th anniversary and one on our 20th anniversary. I’m not going to write another one until the 30th.

LAIRD: Weird. Zadie writes me a poem on our anniversary as well.

CHABON: There’s something about the occasion that seems to call for it. I don’t think I could do it every year. It takes such a long time to write a poem. Sometimes, though, I’ll write a paragraph and think, “If I paid more attention to the line breaks and the enjambment, this could be a poem.”

LAIRD: I think the best literary fiction has that quality. And that’s why I was mentioning your metaphors. One that really stuck with me is when you describe a coffee table as being like a footprint without toes. [Chabon laughs] On the surface, it’s sort of straightforward and visual, but something else also happens. There’s this faint suggestion—perhaps we don’t even consciously pick it up—of giants among us, or huge invisible forces. Sometimes the best thing about a metaphor is that you don’t quite know why it sticks with you. It just introduces a mystery in some way. Do you think metaphors come from the way writers’ minds are wired?

CHABON: They tend to come to me the same way I’m assuming they come to you, almost as analogies: “This is like that.” One of my first thoughts is often, “What does that look like? What does it literally remind me of?”

LAIRD: It seems to me that metaphors come down to a certain idea of interconnectedness—that everything relates to everything else. Metaphors don’t believe in autonomy. And in the end, perhaps that idea of interconnectedness is a moral position.

CHABON: I think you’re right. I have moments where I find surprising evidence of patterns, like forking tree branches that look like veins in your eyes—

LAIRD: Or a river delta.

CHABON: I don’t want to get too heavy about this, but it does happen where you see the interconnectedness from the macro to the micro, all the way down to the veins in your eyes. But then I also dismiss that thought as too consoling. That’s going on in your novel, too, that push between randomness and pattern, plan and lack of plan. I mean, it’s always amazing when a large portion of the world is willing to see the face of Jesus in a tortilla.

LAIRD: We probably shouldn’t talk about Trump, but it’s kind of like how a huge portion of Trump voters are incredibly pleased with how he’s performing. They see what they want to see.

CHABON: Our brains are wired to find pattern where there is none because, on some primitive level, it’s better to find the pattern and say, “Every time I stick my hand in the tree I get stung.”

LAIRD: Yes, or how certain splashes of color in the foliage mean a tiger is lurking there.

CHABON: Writing fiction can be like tricking other people into seeing what’s really just a bunch of blobs on canvas as shimmering water lilies. Now, let me ask you—you’ve been living in New York for eight years. I wondered how living there has affected your writing, as opposed to being in Northern Ireland or London?

LAIRD: In terms of poetry, I worry about being far from the voice of my childhood, the rhythms of Ulster speech, and the liveliness of its dialect. I know there is a vitality to New York talk, but living among people of different cultures does mean you’re forced to homogenize and lose the interesting words and phrases in order to be understood. You have to deal in the lingua franca of the city, and I worry there’s a certain bleaching involved. But I’m also bored of hearing my own accent. My wife has to order food or taxis on the phone since I can’t be comprehended anyway. But in terms of fiction, I don’t worry about it so much. Wherever I’m living, in Rome or Boston or Warsaw or London, I just hunker down with the work and try to keep going. And New York is great for writers insofar as you can pay someone to bring you food, to take your washing out and bring it back clean. It enables you. Writers always feel guilty when they’re doing anything but writing, and New York allows you to really write all the time if you want to—though my kids put a limit on it.

CHABON: One thing that fascinated me about your new novel is your focus on cargo cults. How did you get into that topic?

LAIRD: I’d been reading about cargo cults for about 20 years. The whole novel was arranged like a fever dream where you have these two separate realities—Ulster and New Ulster—and they end up having certain similarities. Cargo cults fascinate me partly because Christianity itself is in many ways a cargo cult. David Attenborough went to the South Pacific in 1959 and spoke to this cult leader who had been waiting 20 years for this mystical figure John Frum to return with cargo. Attenborough says, “Well, it’s been 20 years. Do you think he’s coming?” And the leader replies, “Well, you’ve been waiting 2,000 years for Jesus Christ.” John Frum is perhaps the most famous example. They think he was an American soldier stationed in Vanuatu during World War II, and he was really good to the local tribe, giving them various implements and clothing and food and these futuristic objects they’d never seen before. This tribe was living a Stone Age existence, and suddenly Americans arrive with Jeeps and iceboxes and stuff they have no hope of understanding. And then the Americans leave again. And John Frum—people think that’s a corruption of “John from America”—becomes a Jesus-like figure that they hope will return and rescue them.

CHABON: Did you do a lot of research for Modern Gods?

LAIRD: I just read a million books. Zadie would keep saying to me, “Can you please stop ordering books on Papua New Guinea?” We had bookshelf after bookshelf of them. They were taking up the whole house.

CHABON: Ayelet goes on binges of ordering books she thinks she might need for writing.

LAIRD: That time of preparing could last forever. You sort of have to shake yourself out of it. And then, of course, when you go to write the thing, you use almost nothing of what you’ve researched.

CHABON: You and I have talked before about how narrative form has really been taken up by television, and how movies have largely abandoned the pleasures of unfolding narrative in exchange for—

LAIRD: Fireworks.

CHABON: Pure spectacle. It’s funny, when you go back and watch even the second-rate movies up to the mid-1980s, you now can’t believe major studios made them. They looked so sophisticated by comparison.

LAIRD: There used to be one writer rather than a team of writers. It’s the old line about a camel being a horse designed by committee.

CHABON: [laughs] Although, I think the studio system always relied on teams of writers. Maybe the difference was that the director or producer had more of a hand in shaping the film. And they were still so limited as to what they could do with special effects. Now when a movie even nods in the direction of a compelling, coherent narrative, it’s a masterpiece. But maybe television has stepped in to fill that gap.

LAIRD: I really like The Night Of, which Richard Price wrote. But I think for some of those long series, you start to feel they are cheaply pointing you in the wrong direction just to fill out the time demands of the episode. To me, there’s a danger in not having the freedom to let the story go where it needs to go.

CHABON: It can lead you on a wild goose chase to make the story last 10 or 13 episodes. I’m enjoying the Marvel stuff on Netflix, like Luke Cage. But in my opinion, that show would have been better as six episodes rather than 13. So yeah, that does happen. There’s always that tension between plotting and what the character wants. It’s like an Etch A Sketch, where one dial moves the line horizontally and one dial moves it vertically, and if you hit the right balance, you get a diagonal. And it’s hard to get that diagonal. I always remember this line from Norman Mailer when he reviewed Tom Wolfe’s A Man in Full. Mailer was talking about how at a certain point Wolfe starts to betray his own character by having him do things that were simply in the service of the plot or just not true to the character as we’d come to understand him. Mailer had this line: “Sooner or later, plot presents its bill, and dire exigencies come down upon the writer. Even one’s best characters have to be ratcheted away from believability.” That’s a danger I’m always watching out for. But on the other hand, I don’t want to go the opposite direction because I want my stories to have forward momentum—to find that diagonal.

LAIRD: The sweet spot is when it seems organic that a character would behave a certain way.

CHABON: Ayelet is my first reader, and she has a really sensitive detector for those moments my characters do things that feel inauthentic. Some days she gets very upset with me: “How could you have this character do that?”

LAIRD: Zadie is the same. I’ve only written three novels, but they’re always about twice the length they end up being before Zadie goes through them and says, “You’ve already shown this side of the character. You don’t need this. Take it out.” Or, “We’ve already had this emotional beat. We don’t need more of it.”

CHABON: Don’t you want to say to her, “Zadie, most readers are not as smart as you”?

LAIRD: [laughs] No. I just immediately submit. [Chabon laughs] I don’t take pointers from people on poetry, but I do when it comes to fiction. For poetry, I’m happy for people not to get it the first time. I don’t think there’s any law where you have to read a poem and immediately understand it. In fact, lots of good poetry doesn’t work like that, so I don’t mind a bit of mystification or difficulty. But in terms of fiction, the person who lives in my house happens to be a really great fiction writer. But more than that, if a reader reads it and they’re like, “This feels repetitive or wrong or untrue,” then I think you have to take those notes into account. It’s very hard to see those weaknesses for yourself. For example, you can fall in love with a line or an image even when part of you knows you really don’t need it.

CHABON: Often, the lines or passages that get moved when I’m doing a revised draft are the ones I labored over the longest. Like a sentence I spent three hours working on.

LAIRD: That’s what Samuel Johnson said: “Read over your compositions, and wherever you meet with a passage which you think particularly fine, strike it out.” [both laugh] It’s good advice. Kill your darlings. You’re trying to achieve a certain smoothness, and you don’t want something sticking its head above the parapet.

CHABON: What’s strange is when you’re rereading or editing your book and you start to expect that this work is going to be reviewed, and you can sort of tell which line is going to show up in reviews. There are always a handful of sentences that reviewers tend to single out for praise or blame.

LAIRD: They’re like the keystones of the book.

CHABON: It’s a disturbing realization. Because you begin to wonder, “Is this sentence just a crowd-pleaser, or is that in itself a bogus reason for cutting a sentence?”

LAIRD: Do you worry about a book’s reception while writing it?

CHABON: I honestly don’t think it makes a whole lot of difference one way or another. That’s my 30 years of experience. At this point, I’ve had rave reviews in prominent places, I’ve had bad reviews in those same prominent places, and I’ve had everything in between. In the end, it always seems to be completely unrelated to why a book might do well or not. It’s like an alchemy that has nothing to do with reviews or critics or promotion or marketing or which radio shows you got on or didn’t get on. You could do everything right, have tons of attention and coverage, and have the book really kind of go nowhere. Or you could do nothing and then some bookseller decides it’s her favorite book, and she forces all her customers to buy a copy, and it mushrooms from there.

LAIRD: The whole process of having to put the thing into the world seems so antithetical to the act of writing. Poetry is slightly easier, because there’s less money and fewer people involved. You just let a book of poems trickle out in the world, and it finds its own people. Novels are much harder, and you don’t think you should have to do some of the things you’re made to do.

CHABON: Well, anyone who becomes a writer because they want fame and attention is a fool. You become a writer because you like to be alone in a room with your books.

LAIRD: Like that Nabokov quote: “I think like a genius, I write like a distinguished author, and I speak like a child.” I wouldn’t claim the first two, but I definitely talk like an idiot as soon as I have to go out and make sense in public. [laughs] The whole point of writing poetry or fiction is that you get to agonize over whatever it is you want to say, and you finally say it, and you get it as perfect as you can make it. Then you’re forced to babble freestyle.

CHABON: I often get the question about accounting for the invention of a book. Like, “When did you start writing this novel?” The answer is never true. I end up telling two or three different lies, sort of myths of origin, because the actual answer is utterly unsatisfying and I don’t even really know. Yes, there were certain books I was reading at this moment or I had an encounter of this sort, but I’m always reading books, I’m always having encounters, I’m always taking trips. Whatever it is you come up with about how you got started, that’s equally true for all the books you didn’t start.

LAIRD: In a way, the book itself is the answer to that question. The reason that the book exists is because there was a gap in you. You wrote the book to fulfill that gap in some way. That’s what the answer is.

CHABON: Absolutely. And anything more is made up on some level. We are accustomed to an answer like John Fowles had for The French Lieutenant’s Woman, where he saw a woman walking or had a vision of a mysterious woman walking, and the whole story grew from there.

LAIRD: Total bullshit. [laughs] And you’re right—part of the goal of an origin is to have the myth. Maybe next time someone asks, “What’s the book about?” we should say, “It’s about 425 pages.”

MICHAEL CHABON IS A PULITZER PRIZE-WINNING AUTHOR. MOONGLOW, HIS NINTH AND MOST RECENT NOVEL, WAS RELEASED LAST FALL.