Julie Taymor

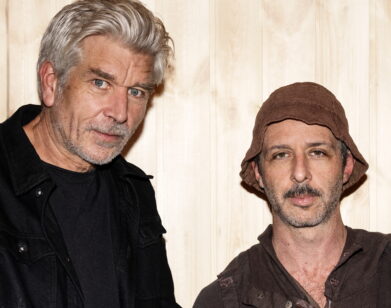

On February 19, director Julie Taymor and her friend, the actor Alfred Molina, with whom she’d worked on both Frida (2002) and last year’s film adaptation of The Tempest, got together for what would become a wide-ranging discussion on theater, art, her creative process, and, of course, Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark, the endlessly scrutinized, $65 million musical that Taymor had spent the past nine years working to bring to the stage. The scope of the production on Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark was always designed to be immense, built around a mythic retelling of young Peter Parker’s transformation into the web-slinging crime-fighter Spider-Man-an ongoing saga chronicled in comic books for more than four decades-filled with moving set pieces, elaborate costumes, complicated special effects, tricky aerial maneuvers, new characters, and epic rock songs by Bono and the Edge from U2. But, as is now well known, the show itself would soon become a fraught affair, beset upon by numerous delays and ballooning budgets as well as the death of its original producer, Tony Adams, in 2005.

Nevertheless, when Taymor first agreed to do this interview, Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark had been in previews for nearly two months, and she was in the final stages of prepping for its newly scheduled opening on March 15 (postponed from its previously scheduled opening date of January 11, which was pushed to February 7, which itself was postponed from another previously scheduled opening date of December 21). But, by then, it already become the pop-culture equivalent of a punching bag, as a string of mechanical malfunctions and injuries to the cast began to mount, prospective opening nights came and went, the longest preview period in Broadway history got longer, and critics broke tradition by reviewing the show before it officially opened.

On March 9, less than three weeks after Taymor and Molina spoke, the lead producers of Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark, Michael Cohl and Jeremiah J. Harris, issued a statement announcing that the show’s opening would once again be delayed, and that Taymor would not continue in her day-to-day duties as director due to “previous commitments” that would not allow her to see through any additional tweaking and honing of the production beyond March 15. Another director and a script doctor were brought on board. Production would be shut down for three weeks. Bono and the Edge said they were working on new songs. And a new opening date was set-yet again-for June 14.

We initially wanted to do this interview with Taymor because of the level of creative ambition that seemed to drive her vision for Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark. It’s a trait characteristic of much of her wildly inventive body of work as a theater and film director and costume designer, which has included radical stagings of Shakespeare, operas like the hugely successful production of The Magic Flute in repertoire at the Metropolitan Opera, risky films like Across the Universe (2007), which told the story of two young people in the ’60s set to the music of the Beatles, and commercial boons like her stage adaptation, with songs by Elton John and Lebo M, of Disney’s The Lion King (1994), which has grossed more than $4 billion since it debuted in 1997. Ultimately, Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark might very well represent a kind of victory for Taymor, too: in its spectacular, if imperfect, quest to break new ground, the show is experimental in every sense of the word, and despite all of the controversy, it continues to play to packed houses and remains one of the highest-grossing productions on Broadway right now. But more than critical praise or big box office, Taymor, from the beginning, seemed first and foremost determined to put together a show that would be like nothing that Broadway had ever seen before. And, in the end, she has done just that.

ALFRED MOLINA: I was going to ask you to start at the beginning, if you don’t mind.

JULIE TAYMOR: It sounds like the way we deal with the beginning of Spider-Man. The origins…

MOLINA: Well, you haven’t opened yet, and I think it’s unfair to start speculating about that. But I was looking at these massive migrations from one nation to another, from opera to Disney to Balinese puppetry to Hollywood movies, that you seem to have had in your life. On the face of it, they do seem like incredibly wide-ranging, paradoxical places to have gone. But if all these things have one thing in common, it is this sense of searching, of seeking something. Your parents were academics, weren’t they?

TAYMOR: Well, not really. My mother is in politics and my father is a doctor.

MOLINA: But presumably at home you were encouraged to study, to be inquisitive.

TAYMOR: Well, yeah. I had a tremendous amount of freedom as a kid. I was the youngest of three children, and my older brother and sister, who were six and seven years older, went through the hell of the ’60s with my parents, and that’s what you see in Across the Universe. You actually see Max and Lucy… And that family isn’t exactly mine, but I watched that time period and saw what my parents went through. I started to go out of the home at about age 8, 9, 10, to Boston Children’s Theater, where I was studying acting. The kids in this theater company were from all over Boston. That began something that was very important to me, which is to go outside of my own milieu, go outside of my own comfortable location and put myself into a place where I would learn or be exposed to things that were more challenging, and new worlds. Then, when I was in my teens, I worked with Theater Workshop Boston, Inc., which is an experimental theater company. This was during the Grotowski time and the Peter Brook era where actors would actually create their own productions. I was 15-16 years old, being exposed to how you cannot just follow a prewritten script, but really induce the material or derive the material from research and from exploration and from improvisation. But at that age I felt like I wanted something more formal, so I graduated high school early and went to study mime at École Internationale de Théatre Jacques LeCoq in Paris. That gave me the beginning of an understanding of the power of the body and what you can do with physical and visual movement, masks and puppetry. I think that was an era where theater companies, whether it was Mabou Mines, or a number of theater companies, would create with the actors… They would bring up the material themselves out of their own experiences. It was very exciting, because you used yourself as a writing pad. You used your body, you used your brain and your emotions to put out the material. You weren’t just tools of a prewritten script. It was very exciting because you used yourself as a writing pad.

MOLINA: Now, physically, you’re a very free person yourself. Is that something that you are attracted to in performers?

TAYMOR: I don’t know if I would use the word free as much as I love actors who know how to utilize their body as an expressive part of their portrayal, almost like a moving, living sculpture… I don’t know if I’ve done this with you, Fred, because we’ve not done theater together, only the films, but one of the ways that I begin to work with actors often-and even with Anthony Hopkins in Titus [1999]-is to find the ideograph of a moment, to reduce a character to its essence, like a Japanese brush painting. In Titus, for instance, there is a theme of hands, and if you watch Hopkins through that film, you’ll see how the hand-because he loses his hands in the film-is about power, and how he touches the head of Lavinia, and how his hands and his gestures really are the ideograph of what he’s expressing inside, the emotional landscape that is inside.

MOLINA: This is interesting because this idea of ideography, of finding the essence of a character… Is this something that is applicable to any form of theater that you’ve been involved in? Can you apply it to anything?

TAYMOR: I would say yes. Even in something like The Lion King, which is very simple to discuss. The Lion King‘s ideograph is the circle. So you will see it in how Pride Rock moves up out of a hole. You’ll see it in the giant sun in the beginning, or the circle of Mufasa’s head, or the circle of the silk that gets pulled down into the hole to represent drought in Act 2. If you were a painter and you had to, in a brush painting, say, “Well, what is the essence of that piece?” You are looking for that ideograph. It helps designers and directors to come up with: “Well, what is the set? What is the concept? What is the whole?” Then you tell the story of that ideograph. It can come in a literal, physical form. If you’re saying, “What would the ideograph of Scar be?” And it’s a serpent-he’s slimy, he’s irregular, he’s all angles, he’s not straight on, he’s not balanced in that way-so even in the mask or the movement of the actor you see that crooked nature. So it helps actors in finding their character. It also helps designers in finding the essential set design.

MOLINA: I was looking up some quotes of yours. You once said in an interview, “I don’t think anything really creative can be done without danger and risk.” Does that come from some personal experience, or is that just an intellectual notion that has captured your imagination?

TAYMOR: I think first it comes from personal experience. There was one seminal moment that I had when I was 21, on top of a volcano. I had been in Indonesia for two years on a fellowship and was studying visual theater, and finally was coming up with the notion that maybe I would create theater from scratch in Indonesia, with Indonesian performers, Javanese and Balinese. I met a French gypsy Algerian actor who had parachuted himself down into the jungles of Sumatra, and we decided to take a journey up to the live volcano of Gunung Batur in Bali. It was erupting every 15 minutes, and here I was in rubber thongs, holding onto roots, going up this volcano, this dead crater, which looked very high… We got to the rim, to the top, and Roland disappeared in the sulfur smoke about 30 feet ahead of me, off the other side, where we saw fire erupting every 15 minutes-not lava flows, but spitting fire. It was windy. It was crazy. I’m not in hiking boots. I’m on the edge of this crater, and I look straight to my left, and you’re looking down into this dead, dead hole-and I couldn’t get across this 20- or 30-foot precipice if I didn’t do one thing, which is get down and crawl on my hands and knees like a cat, because sheer rock face was to my right, which was peeling off or falling off, and to my left was this hole, and straight ahead of me was sulfur smoke and this spitting volcano. I remember… These were the years of-not that I was a druggie-but these were the years of Carlos Castaneda and this kind of talk about how to focus and put the blinders on. Then what happens on the other end of that is, I looked into the live crater, and I saw something I would never see-and it was magnificent to see. Of course, now I’m in the middle of Spider-Man… But that is something that relates to many of the projects that I like to do. Often they are about outsiders. Often they are about magic, transformation, myth. And Spider-Man has this contemporary myth.

MOLINA: I always thought that the great attraction of Spider-Man was that at the center of the story you had a hero who was a reluctant one, much more than other comic heroes who seemed to sort of love the idea of being heroic and super-famous. I always thought that Superman was kind of… I couldn’t understand why no one recognized him as Clark Kent.

What I adore is the juxtaposition of high tech and low tech. It’s sort of like I love the sacred and the profane. I love to put these extremes in the same hopper.Julie Taymor

TAYMOR: I agree. It’s just those glasses, right?

MOLINA: Yes, just those glasses. I never quite got that. Batman seemed to be living this wonderfully fabled life, even without being Batman.

TAYMOR: Well, he’s very wealthy, yes.

MOLINA: I couldn’t relate to any of that. But Peter Parker reluctantly becomes Spider-Man, and he’s constantly battling with this new responsibility, this weight that he’s carrying.

TAYMOR: Anybody could be Spider-Man in this lexicon. Anybody can put on that mask, and if they believe that they have the power, whether it’s to do good, save people, do a minor change-that’s what this is all about. The fact that he is the Everyboy from Queens who is bullied in high school, who can’t get the girl next door, who has trouble making a living… He is a character that most people can relate to, and globally that’s true. It’s not about race or privilege, or even gender, for that matter.

MOLINA: Since we’re on the subject of musical theater, let’s talk about music: your relationship with Elliot [Goldenthal, the composer and Taymor’s longtime partner and collaborator], which has been incredibly fruitful over many years. Musical theater is something that, in a way, I would say you’ve redefined-not just with Lion King, but also in terms of some of the operatic work that you’ve been involved in as a designer and a director. What is it about musical theater, and also music generally, that seems to capture your imagination so strongly?

TAYMOR: I think that both musicals and opera have a capacity to get to an inner emotional landscape. When you break into song, it’s not about dialogue, it’s not about how you would speak in a naturalistic sense-it’s about expressing your inner torment or your inner joy. They can be anthemic or they can be very personal. Working with Bono and Edge, when you actually hear these lyrics, they are the gamut of that. Some of them are saying things as simple as “I wish I didn’t have to wear these glasses,” and others are huge: “You can rise above, reach for the skies above, you can rise above yourself.” They are states of being.

MOLINA: So presumably you would agree that the characters start to sing, burst into song, when words simply aren’t enough.

TAYMOR: Yes-when dialogue isn’t enough. When an exterior relationship between characters is not expressing what’s going on inside.

MOLINA: It’s the soliloquy.

TAYMOR: Yes, exactly. That’s why this was very interesting in this proposition of doing Spider-Man. Everybody knows and loves that Spider-Man is an action figure. A little girl called this action theater, which I thought was pretty cool. We’ve been calling it circus rock ‘n’ roll drama, but I love this notion also of action theater. In that action mode, we have the lead actor fly quite often on it; he does his own flights. But that’s when he’s unmasked. When he’s masked, it’s going to be a dancer flying through the air. We have 10 of them that take on that action movement of lifting off over the heads of the audience to do his savior role. But he’s not going to sing in that mode. The Peter Parker that you were talking about earlier is the troubled teenager who is funny, he’s self-deprecating, he’s full of quips, he’s really frustrated with his life… In the second act, we have the sort of rise of Spider-Man, the fall of Peter Parker. He is tormented by trying to be the hero and at the same time have a regular life, so he has a lot to sing about. But this gives us material, fodder for songs.

MOLINA: Did you go to Bono and Edge, or was it the other way around?

TAYMOR: No, it was the other way around. Tony Adams, who was the original producer, called me up and asked me if I would be interested in doing this project with Bono and Edge, and that was an exciting proposition. It felt like a rock musical, and the right sensibility for something that is a teenage story, a comic book being brought to life on stage, with mostly rock songs. They’ve done an amazing job of also doing songs for characters like Dr. Osborn or the Green Goblin, and this figure of Arachne, who is the origin of the origins, the original Spider-Woman, who figures very strongly especially in Act 2. They have voices for Mary Jane. They actually have found their inner girl, I think.

MOLINA: The huge technology that is involved now in a show like Spider-Man, the computerized wiring and all that stuff… When I did Spider-Man 2 [2004], the movie-

TAYMOR: You figure a little bit in this.

MOLINA: Oh, good. Because I had never done anything like that before, and I found myself completely fascinated by this equation that the actors had to solve between all the things that we are concerned with-character, the emotional life of the character, and so on and so forth-with all the technological requirements. Having to somehow marry these two seemingly paradoxical states.

TAYMOR: What I adore is the juxtaposition of high tech and low tech. It’s sort of like I love the sacred and the profane. I love to put these extremes in the same hopper. When you see these guys fly in Spider-Man-of course there are computers; there’s no way you could do it without them-what they are actually doing requires incredible physical skill and rehearsal. But when we stop… That’s why we call it a circus, because sometimes, if their balance isn’t exactly right on the pendulum swing, they won’t land properly. It’s not like they are computerized. It’s just the movement of what we call the bushing, the things above. Spider-Man doesn’t fly without threads anyway, so the revealing of the strings was also a big part of it, just like in The Lion King you see the strings and the rods-it’s apparent. That’s enjoyable, that you see how it’s done. That is the low-tech aspect, and it gives the actors a tremendous sense of their character. For instance, when Peter gets his powers and he starts on the ceiling of his bedroom, he is literally attached to the ceiling of a red room with four walls, and we have a song called “Bouncing Off The Walls.” He’s on his wires, but he literally leaps and bounces from wall to ceiling to bed to back wall, and does these spins, and as the actor is singing this, he is doing what he’s talking about. He is literally bouncing and the walls come apart. It’s highly theatrical. The walls are held by human beings. They don’t always do it the same way. In that sense, it is true circus. It changes every night. Sometimes it’s better than another night.

MOLINA: So effectively your vision of Spider-Man is very much in keeping with your whole sort of history of work, really. It’s not such a sudden leap away from the Julie Taymor that we all think we knew.

TAYMOR: Whatever that means, but yes.

MOLINA: It’s as if you’ve cross-fertilized a lot of theatrical ideas that you’ve been using for years and years.

TAYMOR: It’s written like a movie in the sense that there are 20-25 scenes in the first act, and then the same in the second act. So it flows very quickly, like a pop-up book. When we have the Queens row houses, it’s flat. Peter is walking home on a conveyor belt. As he sings, and what would be “turns the corner” to another street, this flipbook just slowly turns with the music. The emotion is not just in Peter singing, but in how that piece of scenery turns, and when it turns these flip-books turn the other way-you realize he’s going down another street that maybe, instead of blue houses, they are orange, but they are exactly the same. They are those row houses that get repeated and repeated, and finally they open up, and there are the two houses of Peter Parker and Mary Jane Watson. Even though it’s a computer that makes that scenery move, it’s like a child’s toy.

MOLINA: I saw a clip of that sequence on a 60 Minutes thing, and it struck me how it felt a bit like the way one used to play with toy theaters.

TAYMOR: It’s very much like that.

MOLINA: I also thought it was reminiscent of the New York sequence in Frida [2002].

TAYMOR: Well, it did have that sort of collage-graphic-walking through. George Tsypin and I really wanted to bring comic-book culture onto the stage-and not just the contemporary look of comic books, which we have with these big giant cityscapes of Manhattan that are literally printed on fabric and lit up and move giant cutouts. We also wanted to honor the older version of comic books in this style-the graphics. It’s very beautiful to me. We play, like comic books do, with close-ups and long shots, but very graphically. When we do the death of Uncle Ben, we actually fragment it into comic book frames where you see the moments that a car is being stolen. You break it down. A car accident on stage where Uncle Ben gets run over is very hard to pull off in theater-we all can see it in a movie. So you have to find a stylized way to get those beats, and we do it through frames or cells. Then the low-tech moments, like the wrestling match. We use a giant blow-up doll of Bone Saw McGraw, and the Geek Chorus is manipulating it right there, and bouncing it. It’s about 10 feet tall, and Spider-Man, who is a wonderful, agile dancer at this point, is able to fight with this blow-up doll. It is what it is, and there is a joy in not being so overly technological and perfect. Hopefully it has a playful aspect that then is juxtaposed to some of the scenes that are much more spectacular.

MOLINA: This notion that you see the wires, you see the workings of it, which in themselves can become, in a sense, sort of balletic.

TAYMOR: It’s not something that can just magically happen. The wire management alone is a ballet, as you say. It is a ballet to see these wires going across the sky and these bushings flying around. But it’s all within this web that George has created. So it fits. When you talk about the ideograph of Spider-Man, it is being caught in this web. He is freed with the threads that let him fly across the city and move from building to building, but at the same time he is caught in this web that is not allowing him just to be a regular guy.

MOLINA: I remember going to see a play at the Aldwych [Theatre]. I must have been about 14 or 15. It was a production of Jean Genet’s The Balcony. We were sitting high up, and they had this huge scrim that came down to denote a scene. From the angle where I was sitting, I could see the actors behind the scrim going into quick changes. I can remember watching and just loving that.

TAYMOR: This is exactly what happens in the balconies in Spider-Man. The screaming and roaring from the balconies is the most fun. Spider-Man actually lands-and Arachne and Peter as well-on the balconies, and you watch them get hooked and unhooked. Sometimes they take off. Arachne has to be preset up there. Yes, you’re following the story, but for a moment you’re watching these artists take off. When he lands, to hear these girls up there… Last night it was fun. It was like being at a concert. You heard them screaming when he landed. Then he’s waving to them, you know, the little kids. That is where the dimensionality of it, the duality of watching a play being put on and in the story at the same time.

MOLINA: It’s that contract that we enter into. We know we’re in a darkened room, witnessing something. But there again, that goes right back to the early roots of theater as religious spectacle.

TAYMOR: And as a shamanistic experience… You know that the shaman or the ducan or the witch doctor is going to put on that mask, and you’re willing to take the journey with them to the underworld or to the other world to do this ritual.

MOLINA: Can you tell us what you saw in the mouth of that volcano?

TAYMOR: [laughs] Well, I saw bubbling lava, and at the same moment I saw a reflection of a certain kind of inner turmoil. Because at the moment I looked into that crater, I slipped, and a large piece of volcanic rock took a hole out of my leg. The scar is still there 20, 30 years later. But it’s one of those things that reminds you of the kind of risk or the kind of moment in order to push yourself. The beauty is when other people want to go with you. You don’t do it alone. You have to be on the ride with a lot of people. But that moment of being, as Peter says, being on the precipice, so that you can try to fly somewhere you’ve never been, that’s a totally thrilling ride. I don’t do it just for the hell of it. I do it to obviously find another place of understanding of material that attracts me and material that attracts people. When we explore this material, we know that we are dealing with something that is… I don’t mean sacred in a kind of untouchable way, but that it’s adored, beloved, has lived there for a long time. This contemporary myth is something… the hero story, the hero journey, it’s not new. It’s there from the beginning, this idea that we… We tell myths over and over again, lest we forget who we are, lest we not understand that these tales take us through the darkness of our lives, and they put us into a place where you understand what it is to be human.

MOLINA: Wouldn’t you be bored if you did it any other way?

TAYMOR: I don’t know if I could do it any other way. It’s sort of what is just my nature, or what is natural. It’s the way that I explore something, and then when I bring other collaborators in on the journey, they want to do it, too. Bono, Edge… It’s what we get out of bed in the morning to do-to say, “Wow, what does it mean to be Icarus flying to the sun, the boy falls from the sky… What is it?” You put on those wings. Will you be able to fly or will you fall? That’s a major theme. The boy falls from the sky. It’s sort of horribly emblematic and, at the same time, the absolute theme is “and you can rise above.” We feel connected to this material because we know that really in the Spider-Man mythology, there is a greatness to it that makes it so… It’s transcendent. It speaks to all ages. One of the reasons why I love to do Shakespeare is that this great artist was able to talk to a wide variety of audiences. He could do the bawdy plays and the humor and the clowns-as you know, because you’re a wonderful Stephano-that speaks to the populace, the masses, the groundlings, whatever. They get into the story through that door. But then he can do in the same play, histories, poetry, magic, and there are multiple doorways and levels at which a variety of audience members can hook in. That, to me, is what a show on Broadway, or a large opera or large-scale piece, has to be. You don’t have to have everybody understanding every single moment, but they have to find a way to hook in. We have gotten such a wide gamut of what people like that it’s not like there’s one consensus, whether it’s a child of a 50-year-old or a Glenn Beck. It’s so interesting, and that’s what I feel a show like this can do. You really are able to say, “I went there because I loved the songs,” or, “I loved the story,” or, “I didn’t like this but I liked that.” You’re able to hook in whatever you can. That’s a very strong belief I have about when you create something. You can’t patronize your audience. You don’t have to spoon-feed them. If there’s enough that excited them in an aural and imaginative way, then they get to go home and think about it. Children have an easier ability to tap into the surreal than adults do, in a funny kind of way.

MOLINA: Well, they’re less encumbered.

TAYMOR: They are much less encumbered. If they’re bored, they’ll let you know. But if they are entertained, their imagination really takes over. In The Lion King, the characters sing in Swahili and Xhosa and a whole bunch of languages that aren’t English, and everybody knows it’s about the sound and the emotion of those songs, not about the literal translation of them. Children get that white silk streamers that are pulled out of the masks are tears. They don’t go, “Oh, daddy, what is that white silk coming out of the eyes?” They understand the emotion of it. Because that’s the way they do make-believe. They are able to put something and say it’s something else. They can pick up a ball of yarn and throw it, and say, “Boom! That’s a bomb falling on you.” They are able to quickly transform an object into something other than it is, and something more powerful than it is. They see it, and it happens, and they believe it. I love that. I love that way of thinking, where you kind of just go to it in a childlike manner, just let it rush over you and see if you can just be there with it at that time.