Grant Achatz Cooks Up Emotion

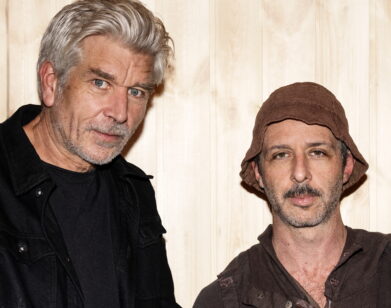

ABOVE: GRANT ACHATZ. PHOTOS BY FRANK SUN

When Grant Achatz shakes your hand, you immediately get a sense of how he runs his kitchen. He looks you directly in the eye, sternly, for a moment, gives one firm shake, and swiftly recoils to his former posture, relaxed but dogged. The precision is there; so is the sort of aplomb that lets on he knows his salty from his sweet from his acidic, every shade in between, and he won’t settle for a degree in the wrong direction.

It is, after all, an unfathomably delicate act he’s balancing. As the founder and head chef of the three-Michelin-star restaurant Alinea in Chicago, he’s spent almost a decade elevating food to what most agree is art. And it’s science, applied to food, that’s his means of achieving masterpieces like a bite-sized cocktail, made of poached apple morsel in gelled brandy, or whatever the current menu item “LAMB……..?????…………!!!!!!!!!!!!!” is.

Yet despite all the punctuated intricacies of his creations, Achatz isn’t too concerned about molecular specifics. “Let’s say, I want to harness the smell of burning oak leaves,” he says, referencing a pheasant-based dish Alinea served in fall of 2010, embellished with singed oak leaves on sticks. “The only way I can control that smell is by using a rotary evaporator. Now, that seems really science-y, but we’re just trying to get the smell. I don’t care if it looks like it belongs at a Harvard or MIT lab.” He pauses. “All’s I know is, it’s going to capture that smell.”

Scents have been of uncommon importance to Achtaz, even by chef standards: in 2007, just two years after Alinea opened, he was diagnosed with tongue cancer. Undergoing chemotherapy, he lost his ability to taste, and for over a year relied on his team and his sense of smell to gauge the quality of his dishes.

Luckily, Achatz was armed with a lifetime of experience in restaurants, big and small, to help him through the trying time. A small-town Michigan native born in 1974, he started working for his parents’ chain of diners as barely a teenager. Years later, right out of the Culinary Institute of America, a 21-year old Achatz was hired by Charlie Trotter to work at the Chicago chef’s famous (and infamously intense) kitchen. He eventually went to Thomas Keller’s French Laundry, in Napa Valley, California, moving up the ranks to sous chef during the restaurants’ heyday in the late 1990s. In 2000, Keller arranged for Achatz to move to Spain’s El Bullí. The restaurant, considered among the best in the world, was pioneering the use of molecular gastronomy. It was there, Achatz describes, that he learned to approach food with a wildly innovative bent. After a stint at Chicago’s Trio, Achatz found enough support to open Alinea downtown. In 2010 he opened the high-concept restaurant Next, where guests buy tickets ahead of time, similar to buying seats on a plane. Alinea is now one of three profiled in the documentary Spinning Plates, opening this week. The film gives viewers an inside look at the eateries, which include Breitbach’s Country Dining in Iowa and La Cocina de Gabby in Arizona, and the people behind them.

We met Achatz at SoHo’s Crosby Hotel, where he was staying. At one point, a culinary student came up to us. She asked Achatz to sign her book, and called him an inspiration. Achatz had no visible reaction. But he signed the book and took her card, holding it in front of him for the rest of the interview.

RACHEL SMALL: What was the first thing you learned how to cook?

GRANT ACHATZ: Toast.

SMALL: How’d that go?

ACHATZ: I burnt it.

SMALL: Did you enjoy the challenge of learning to cook new dishes?

ACHATZ: I think it was always challenging. My father would always tell me that creativity didn’t matter at the diner. When I was probably 14 or 15, I would put—I mean, it was a no-nonsense place—but I would try to put a sprig of parsley or orange curl on the omelets, or something like that. He’d be like “Don’t do that!”

SMALL: And then you chose to go to CIA. How did your family react when you came back and were doing these very non-diner-101 type dishes? Was your family surprised at the things you were learning?

ACHATZ: I don’t think they were surprised. I mean, it’s your mother, so she’s always going to be proud no matter what you do. Now they come to the restaurants, either Next or Alinea. I don’t think my mom has ever left the country. She barely flies. She may have gone to California. She’s never been to New York City. She’s very much small-town Michigan. So then when she comes to the restaurants, it’s a big deal for her. It’s like an eye-opening experience.

SMALL: Do you talk about how you create the different meals with her? Does she ask?

ACHATZ: She’s very inquisitive. She follows me on Twitter and tries to keep track of me.

SMALL: That’s kind of cute.

ACHATZ: Yeah, that is kind of cute.

SMALL: Your first job out of culinary school was at Charlie Trotter’s. How was that?

ACHATZ: I don’t remember. My first day, would be him yelling around me. His method of discipline is he wouldn’t address you. He would yell at the person next to you about you. He yelled at me for blanching peaches wrong, and I was. I was blanching them wrong.

SMALL: And now can you blanch peaches with your eyes closed?

ACHATZ: Yes, I can blanch peaches. He taught me discipline and intensity, to push. Say what you will about Charlie. When that restaurant opened in 1989, it was groundbreaking, and what he did, the way he approached being a restaurateur and being a chef, was pretty amazing. One time, I had little bits of basil on the cutting board. I wiped it into my hand and threw it away. I’m talking like, not an egregious amount. He come up to me and he goes, “Do you have your wallet with you, chef?” and I said, “Yes!” and he goes, “Can I see it?” I reach in my back pocket and got my wallet. Then he goes “Do you have any money in there, chef?” I said “Yes.” Then he goes “Can I see it?” I’m a 22-year-old cook, so I didn’t have much money. I pulled out two fives and four singles. I lay it down on the cutting board, and he goes “Is that all you have?” I said “Yes.” He grabbed it, threw it in the garbage can.

SMALL: Oh my god!

ACHATZ: He goes “That’s what you just did to me, throwing away that basil.” And I’m like, “Ah, fuck.”

SMALL: That’s a little harsh.

ACHATZ: Thomas Keller at The French Laundry was the complete opposite. Everything that he did, you felt was the perfect way to do it. It could be from cooking techniques to work ethic. Trotter never cooked. He was very much a director, overseeing the symphony. Thomas, he played an instrument. He would mop the floor. He would cook the food, he would plate the food. That’s really where it happened for me. Those five years at The French Laundry wee phenomenal.

SMALL: From The French Laundry, to El Bullí, then on to Trio, what were the most important lessons you learned?

ACHATZ: The time spent at The French Laundry was the foundation for my cooking—both from a technical point of view and more importantly a mentality. The first time I went to El Bullí was an incredibly humbling experience, because at the time I was a sous chef at The French Laundry. And The French Laundry was the shit, right? You feel like there’s nothing that can touch you, right? Then you go to El Bullí, and you walk in the kitchen and you realize that you basically know nothing. That was the first time I really realized that there could be more to cooking.

SMALL: What do you mean by more?

ACHATZ: When you are trained in French technique and you work at the French Laundry, you have a certain foundation. In my case when I went to El Bullí, you realized that the whole thing just gets flipped right over. Which is exciting for a young cook because you’re like “I can do whatever I want.” That was a big thing for me personally with El Bullí. You can take risks, you can do something different. After being there, I came home back to French Laundry and decided that I didn’t want to cook like that anymore. That’s when I left for Trio and then eventually Alinea.

SMALL: How did you get a team together that you really trusted to carry out the level of precision required in Alinea’s kitchen? I know at one point, while you were getting treated for tongue cancer, you even had people who were tasting food for you and giving you impressions of it.

ACHATZ: A lot of the guys, Jeff Pikus, Dave Beran, who’s running Next right now, come up through the ranks. They’d always come to you and be like “How does this taste chef? How does this taste?” You’d taste it and you’d say, “A little more salt. A little more pepper. A little more acid.” You’re formulating their personal flavor profile. They are learning how you want the food to taste. Then all of a sudden you’re not able to taste, but for a year but prior to that, you’ve basically trained them on how you want the food to taste. I’d put the final stamp on something, but as soon as I couldn’t taste anymore I had to lean on them to tell me what tasted good, which was weird. It was really weird. They did a fantastic job.

SMALL: How would you explain molecular gastronomy to someone that’s never heard of it before?

ACHATZ: See, I don’t even like that term.

SMALL: What do you call it?

ACHATZ: We usually call it “progressive American.”

SMALL: [laughs] That it is, definitely.

ACHATZ: But I feel like [the term] molecular gastronomy makes it feel too sterile.

SMALL: It sounds like a high-school chemistry class.

ACHATZ: The science involved is merely a tool. It’s not the end-all, be-all. It’s not often the impetus for the dish. It’s more about: maybe, how do we achieve that aroma or texture? We might have to use a rotary evaporator, we might have to use a volcano, we might have to use a cryovac machine. But the basis of the cuisine is not formed on that. It’s just one tool. It’s like, if you need to cut a piece of fish, use a knife.

SMALL: Right.

ACHATZ: For instance, burning oak leaves. I feel very strongly that that should be incorporated into one of our dishes because it’s a very significant aroma in my childhood and I want to represent that in this food. That smell is going to be served with that dish, which is the opposite of science, because now it’s about emotion. So that dish gets placed in front of you, you smell burning oak leaves, that immediately transports you back to your childhood. It’s nostalgic. It triggers a memory. That sort of thing. It’s not about the science at all. It’s about the emotion.

SMALL: It seems like weather and seasonality make up a lot of your inspirations.

ACHATZ: As a chef, you need to be aware of seasonality. Tomatoes in summer, corn in the fall, asparagus and morels in the spring. Creatively, we also look at those as jumping-off points. So you look at in the spring, we’re looking at white and green asparagus and morel mushrooms and then we go “All right, what can we do with morel mushrooms?” We will literally sit there with morel mushrooms on our cutting board, going, “The hell are we going to do with these things?”

[a woman walks up to the table]

WOMAN: Excuse me. I know you’re in the middle of an interview. I’m a culinary student. Would you mind signing my book?

ACHATZ: Sure. Yeah of course.

WOMAN: I’m a huge fan of yours. Also the fact that you just made it through a lot of difficulty—I just really appreciate it.

ACHATZ: No problem.

WOMAN: My name’s Mary. [speaking to Interview] He’s kind of an inspiration, he’s someone who has made it through a lot and doesn’t give up. I overheard your conversation. I’ve learned more in listening to him in 10 minutes and watching him… I’m in a difficult level in culinary school. [to Achatz] Thank you so much.

ACHATZ: You’re welcome.

MARY: You’re an inspiration. If you ever need, I’m happy to be your branding expert. [Mary leaves]

SMALL: What other inspirations do you draw on that you think bring out that emotion you were talking about?

ACHATZ: A lot of it I think comes from travel. The month of September, I was only in Chicago for three days. Crazy. I flew to Hawaii, flew right from Honolulu to Tokyo. We were in Hawaii for nine days, Tokyo, Japan for nine days. I came home for my son’s 12th birthday for three days and then flew to Australia for nine days. So you see different ingredients, different cooking techniques. Some of which you want to replicate, some of which you don’t. When we were in Australia, we ate live ants, we ate fried crickets, we ate all that stuff. It was weird.

SMALL: Did you skip the food on the airplane?

ACHATZ: Yeah.

SMALL: Fair enough. In Spinning Plates, I though it was interesting that the other restaurants profiled are small-town operations, similar to your family’s.

ACHATZ: I totally want to visit them. I’m very comfortable in those environments, because that’s exactly what I grew up in. It was a family diner, open seven days a week, breakfast, lunch and dinner. Omelets, eggs, meatloaf, mashed potatoes, Reuben sandwiches, that’s my early life.

SMALL: When Pete Wells wrote about Next opening in the New York Times, he basically said, to paraphrase, that dining has merged with theatrical performance. Would you agree?

ACHATZ: When Alinea opened in 2005, that was our M.O., trying to make it participatory theater. Of course you’re going to get food and you’re going to get seated, but is there ways that we can manipulate the experience to make it more interesting and more telling and we’ve tried a lot. We’ve involved live music into the system that pairs with the food. We created a giant edible tablecloth that we plate the food on.

SMALL: What do you like the most about cooking?

ACHATZ: I think professionally, it comes down to making people happy. People make plans months in advance to fly in, to eat at our restaurant, so I feel like there is a great responsibility to give them a great meal. When we can achieve that, that’s pretty exciting. On a personal level, in a way it’s the same because if I go home and cook grilled cheese or poached eggs or a bagel with my kids in the morning, you’re still sharing that experience. You’re still making them feel happy. I think that’s what it is all about.

SPINNING PLATES IS OUT IN LIMITED RELEASE TODAY.