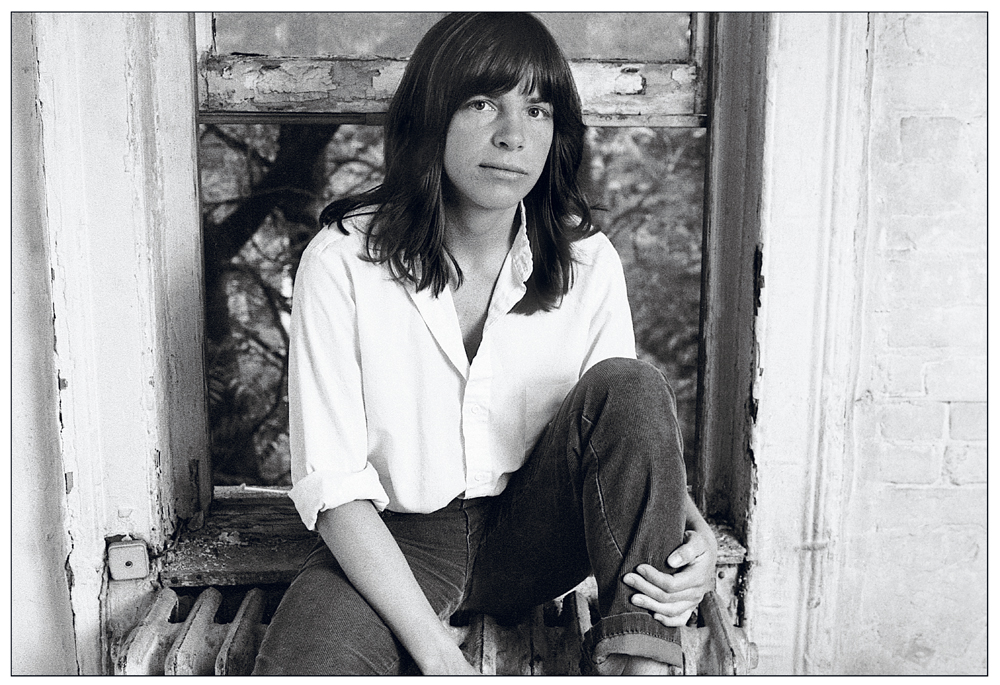

Eileen MYLES

There’s a thing that keeps heaving. My whole consciousness likes to stay as close as possible to falling apart, but not letting it entirely end. That’s my pleasure.Eileen Myles

Eileen Myles isn’t interested in being your fucking legend, nor in hearing her name in the hallowed tones usually reserved for the aging white men of literature. And yet, in poetry, which hardly ever has celebrities, there is a sense—however fleeting—that if you survive long enough, keep beating your head against the status quo, one day, someone, just maybe, might declare you a national treasure. Myles isn’t particularly interested in that because her writing has her own version of fame to declare. It’s the very one signaled by the recent release of her two new titles—I Must Be Living Twice: New and Selected Poems 1975-2014 and Chelsea Girls: A Novel, a reissue of her iconic 1994 text that redefined the queer novel. Myles, who grew up in Arlington, Massachusetts, before moving to New York in 1974, has kept re-creating her terms ever since; being a dyke, a woman, and from the working class are anything but well-worn synonyms for a serious writer in our culture. Even so, given the attention her new books have garnered, as well as her recent packed readings around the country, Myles seems to be happily surviving the vertigo. It’s as if the literary establishment is finally willing to admit that she’s one of our great living poets and writers.

People talk about being famous for being famous. With Myles these days, it’s a matter of becoming famous for being never quite famous enough. But underneath all of these social realities is the one that matters: the reality of the work. Her poems, with their short lines and hard, lyrical phrasing, offer a kind of broken-nose elegance, like the shuffle of a scrappy boxer who’ll still kick the shit out of you. She has never felt the need to write about Life or Poetry or Art or any concept really, but rather the happy accidents of living day to day or moment to moment. It’s a world where words and bodies, in her sweetly mortal imagery, are just themselves as they keep moving. And likewise, in her prose, Myles’s roving camera proves perception exists only as fast as we can keep pace with it, ducking and swerving from the old selves we collect. In maybe her greatest poem, “An American Poem,” from the 1991 collection Not Me, Myles is willing to claim that our perverted national mythos is still worth something—declaring, “Well I’ll be a poet,” then “I became a lesbian.” In return for such a pledge of allegiance, she’s bringing all of our baggage into the room that is poetry: AIDS and homelessness, her awkward Boston accent and the Kennedys, bleeding gums and homosexuality. When she says in that poem, “I am your President,” you know the dark, hopeful thing is that she actually is. I spoke to Myles by phone from New York, when she was on the West Coast stretch of the tour.

ADAM FITZGERALD: How the hell are you?

EILEEN MYLES: I’m good! I just read at Powell’s [in Portland] to a huge audience. Having big audiences when you’re on a book tour is like Valhalla if you’re a person who used to sell Girl Scout cookies on the side. Because you want to give the reading that will sell the most books. One thing is not to read too long. I really just love reading. It’s my favorite thing, performing my poems live. Reading by reading, I just kind of follow my nose. I read any part of Chelsea Girls I’m in the mood to hear that night, and I read, like, ten minutes of it. And then the selection of the poems seems to come out of that. Like last night I read this chapter from Chelsea Girls called “The Kid”—it was about the Eileen character’s father dying—and it was a very emotional chapter. And then when I began to read the poems, they were hers. It was like, duh. I never thought of that before. For the first time, I got the psychic payoff in moving from prose to poetry.

FITZGERALD: Close to a thousand people were at the Poetry Project for your recent book launch. People said it made them think of Ginsberg’s big bash there way back when.

MYLES: A thousand people is the rumor; it wasn’t a thousand, but it was huge. I’m getting good audiences, but, most excitingly, the mix seems to be persistent. I mean, it’s often more white than I’d like, but still it’s always diverse—straight and gay, and young and old—and that makes me happy. It’s so funny—people love to come up and say, “You know, I’m embarrassed to say this, I just discovered you this afternoon.” Well, that’s great. But other people come in with a whole stack of my books and want me to sign them all, as if it’s this terrible burden. I mean, please.

FITZGERALD: I remember a few times going to your readings, and you were always preemptively rolling your eyes at the inevitable intro that would have to include lines like “Eileen Myles, rock star! Please welcome our great underground, cult, punk poet!” It seems people feel comfortable wielding your name as this perpetually off-the-radar, not-mainstream commodity that we already know. Now people are discovering you.

MYLES: People love discovering you. The thing about not being historically a mainstream writer is that everyone feels like you’re theirs, you’re their friend. You know, the joke of this tour is that it’s not unlike when I ran for president [in the 1992 presidential election, Myles campaigned as an “openly female” write-in candidate]. Everybody loved me running for president in ’91 and ’92, because they never knew a presidential candidate before. So in this moment when I’m getting attention, everybody’s excited because they always knew my work or they just discovered it. Like, now we’re all at the party. It’s one for our team. Whatever I’m doing with poetry produced this multitude, and I don’t mean purely in numbers, but the community of people, and that’s just a lot like poetry period—that’s how it goes. When people decide to talk publicly about poetry as an art form and how it’s received, they often get very abject about it: “Nobody reads poetry,” and then a thousand people write back, “No, we read poetry.” There’s an abundance of this negative preaching to the choir, and it’s very similar to the experience I’m having. It’s like poor Eileen, you probably don’t know this person, but she’s really great, and now she has been rescued by the mainstream. People can’t let go of the unit of the poet or the unit of the privacy of their own reception, and that’s the thing that’s weird—the way I keep hearing about all these unknown years in the darkness I had with independent small presses, but no, that’s how poetry is known. It’s like forever—it’s many, many little rooms making a big room. That’s the nature of the art form, and that’s what’s happening for me now. It’s just the little room got big.

FITZGERALD: Spending the last days re-reading the novel and going through your poems, I realize your work has been thinking through these questions of reception and construction all along. Chelsea Girls is very moving in its naked portrait of the poet’s ego, vulnerable but hungry.

MYLES: Right. Well, I’m a poet born in the era of Andy Warhol and a generation that wanted to be famous. And even if that wasn’t necessarily what the poetry world was doing, that’s what the world was doing, that’s what the East Village was doing, that’s what people in bands were doing, that’s what the visual artists were doing. People in nightclubs were saying, “I’m John Sex.” There were all these constructed identities, made-up selves. And even though my fake persona was my literal persona, I was constructing it. I got to New York in the ’70s, and I remember looking at Patti Smith and Bruce Springsteen—these are working-class kids from New Jersey—and I thought, “I’ll be a working-class kid from Boston.” Well, I was a working-class kid from Boston. But I never lost my accent because I felt like that was what I was doing. I didn’t have to perform Woody Guthrie like Bob Dylan did in the ’60s, I just had to make myself be Eileen Myles and let that be my shield. So it’s somewhere between constructing and believing, and I’ve been living that construction for as long as I can remember. But even before I was a poet, who hasn’t been making up a self? How does one have a self? That’s like the great question. Not who am I? But what am I?

FITZGERALD: And did you really think you’d make it? John Ashbery has said that just because he and Frank O’Hara and Kenneth Koch took themselves so seriously, that didn’t mean the rest of the world would inevitably catch up and do so.

MYLES: Now I’m starting to hate the word famous. Part of the glamour of being a poet was always this long reach into the future. You knew you were managing time. You might say that Frank O’Hara and all of them didn’t care about fame, but I always remember Morris Golde, who was the very guy who had the house on Fire Island where Frank O’Hara was staying when he died. I bumped into Morris in, like, 1990 at an opera house in Santa Fe, and he saw me and wondered, “Where did she come from?” He asked me, “When did you come on the scene? Did you meet Frankie?” I never heard Frank O’Hara called that! But the New York I came into was a place that just felt very self-conscious, very coterie, like it was a movie set and the film was being shot, and those were our lives. The impossibilities then were the material. You know, the mortality, the dying, the fact that nobody would ever want to hear from this dyke, and of course, I was going to work with that and use that and talk about that, because I had to, because that was my ecstasy, to be present with who I am. And it’s class, too. O’Hara and all of them went to Ivy League schools and were in the art world, and I think they may have looked at the more ambitious, more immigranty, Jewish guy Allen Ginsberg as a bit of a huckster. I loved Allen, and I watched like a hawk how Allen became Allen. You know how he did it? He sent out press releases. He was the first poet to do that. He worked in marketing. I mean, his hero was Whitman, but Allen knew about marketing and media. When they did the famous reading at the Six Gallery in San Francisco, the only reason the world heard about it was because Allen announced that there would be a reading, and most importantly he knew he had the poem. He had “Howl.” He got his friends together; he got everyone in the room. But he had the silver bullet. I suppose when I read Patti Smith’s account, I miss getting the down and dirty. I always heard she was very climby and would go to parties with a falcon on her shoulder; she was so full of desire. I mean, the whole thing is risky business, you know?

FITZGERALD: I wonder how you think your queerness resulted in your work being delayed from getting attention sooner. I bet even then it was pretty naive to assume that just because gay Beat poets or the faggy New York School could make it through, eventually it just had to be easier for a dyke to follow.

MYLES: Well, even the material in Chelsea Girls isn’t the same now because I wasn’t poor ten minutes ago or last year or last week; I was poor 20 years ago. So you can’t smell the poverty in the same way. It’s stylish, because of two decades passing. All the risky sex and the rape, it’s from 40 years ago so, no, people believe it’s fiction. Because time makes fiction. But still, even to sell my selected poems to a larger publisher was slow—it was hard. Some big presses looked at it and said, “This is really great, but we don’t do poetry,” and then the next year they publish some man’s book of poetry. Or “This is really great, but it’s too big,” and then they publish a big book by a guy like Frederick Seidel. But there’s also a whole thing about women and lineage. At the height of the AIDS crisis, I remember the African-American novelist and poet Melvin Dixon doing this long elegy for his own oncoming death, and he was asking, “Who will call my name?” And he was incanting the names of all these male poets, and there wasn’t one woman in there. I was sitting there thinking, “We’re going be your legacy.” Here I am right now talking about Melvin Dixon. Why won’t you let us call your name? That’s the fucked position of women-in-poetry lineage; it’s always unstable, it’s the oldest story in the world, whether it’s Joan of Arc’s or Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, the woman of power is always taken down as quickly as possible. Muriel Rukeyser was huge when I came to town, then vanished for 20 or 30 years, but if you go to the New York Public Library and look at the letters, there she is corresponding with Charles Olson. She knew all the guys. She knew everybody. But somehow that got stopped.

FITZGERALD: You’ve told me how James Schuyler loved dykes. I know you were his literary assistant for a while. Did that help you professionally in any way, beyond being immensely spiritually formative?

MYLES: Jimmy was great. He was very generous. I hate the word mentor, the professionalization of friendships between generations. I just feel like the fact of friendship is the thing we all adored, like the younger befriends or reaches out to their hero, and for me, whenever you meet some younger person, who has a fire in their gut, a way of being in the world, it excites you. And you love their work, and they love yours, and you want them to carry it on. Because this person lives the way you live or you’ve lived or you would like to live. They’re all kind of horizontal relationships, even if it’s about generations. When I met Jimmy, he told me he had been Auden’s secretary. And he very deliberately put me in one of his poems as his assistant. But when the editor of some anthology saw in my bio that I was Jimmy’s assistant, he said, “Weren’t you his housekeeper?” I said, “No, I was his assistant.” I think what men don’t want is too much feminizing of the history, because a feminized history is a less valuable history, and we have to keep up the value. It’s like women bring down the neighborhood! There was even that recent photograph in The New York Times of people who’d been cultural influencers in New York back when, and there wasn’t a single dyke in the picture. Didn’t anyone in the picture notice?

FITZGERALD: Young, queer poets coming up today have an Eileen Myles to look up to. Who’d you have?

MYLES: There was Jill Johnston. So many of us came to New York because of Jill; we read her column in The Village Voice. The book she wrote was called Lesbian Nation: The Feminist Solution, and Queer Nation came from that. All the nations came from that. First she studied dance, then was a dance columnist at the Voice, then she covered the art beat and the social side of it. She’d write that she was at a party last night, and Rauschenberg was there and Jasper Johns—that was her generation. And slowly, she came out in her column; she had a lesbian column in The Village Voice for about 15 years, and famously, there was a big event at Town Hall in the ’70s, when feminism was a new idea, and she was the dyke of that moment. Germaine Greer and Norman Mailer and Diana Trilling were all at Town Hall. It’s kind of amazing when you think the scale of things at that moment, that publicly problematized and publicized feminism. Everyone’s on a panel at Town Hall having a public conversation, but Jill managed to get some young women to come onstage with her, and she threw herself on top of the other women in her double jean jacket and jeans, and they made out in front of the audience. That was Jill Johnston.

FITZGERALD: Your years at the Poetry Project must have been a real education. You even ended up being the artistic director.

MYLES: It was ’84 to ’86, just two and a half years. But I grew up there. I stepped into that building in 1975 when I was 25, and I went to workshops, and I ran a little reading series for them, and I was on their board. The Poetry Project was my education. I didn’t get an MFA; I just went to every reading at the Poetry Project for ten years. That meant that I saw Gwendolyn Brooks and Robert Lowell and Charles Bukowski, and Robert Duncan and Denise Levertov. Everybody came through in those years. Allen would have parties at his house, and Robert Lowell would be there; it’s just kind of an amazing thing. I stopped drinking in 1983 and had terrible jobs for a year—I was cleaning apartments and releasing helium balloons for a Diana Ross concert in Central Park, and then along came the job for artistic director of the Poetry Project, and it just occurred to me that there was no job in the world that I was more qualified for, because I had done nothing but hang out there for my first ten years in New York.

FITZGERALD: One of the first things I remember asking you was to explain how you discovered how to think in real time inside prose. It manages to generate this illusion of live activity across and down your pages.

MYLES: I think part of what you’re doing when you’re doing something new is that you don’t entirely know that you’re doing it. You almost don’t pay attention. You’re paying more attention to the rhythm than the thing that you’re saying, so there’s a lot of extra language hanging outside the building that you sort of allow to be there so that you’re not always looking at the building. It’s very constructed in a certain way, but I almost don’t want to know that so I can keep building what I’m making from the inside. It’s like when I’m in charge of a flow, and that thing has to keep coming at all costs, so part of my performance as a writer, in the act of writing, is to pretend that I don’t know. I like a little bit of oblivion. I’m safe in that. And it can keep accruing in this kind of way. The overarching thing is just reaching inside. It’s almost the invisible part of the form, like in any violent action movie when you see somebody get killed, and they keep heaving, and it’s like with writing—there’s a thing that keeps heaving. My whole consciousness likes to stay as close as possible to falling apart, but not letting it entirely end. That’s my pleasure.

FITZGERALD: So when did Chelsea Girls get called a novel, rather than something else?

MYLES: I really thought of it as a collection of these movies. I was incapable of thinking consciously of such an edifice as a novel. I was afraid to call it a novel. Whether it’s a poem or an opera or a play, I’ve had to get it all in some terms I knew I could succeed at. I feel like I’m all about success in a certain way, and so I’m always trying to look for the smallest unit that I can manage and then make something bigger out of that. The joke of the making of Chelsea Girls is that my girlfriend, who’s in the book, and I couldn’t make a film because we were so drunken and young and messed up. In one chapter in Chelsea Girls, it’s about us making our lousy little film that I never even saw till the ’90s. But we talked about film all the time; we talked about the movies we would make. But so much of that was about loving in some wonderful, hopeless way the life that we were in and the absolute freedom of the day—being young and excited about being an artist, and just how unabashedly honest we could be at that time and thinking that was the most beautiful thing and that I wanted to represent it in some way. Standing in this freedom, and thinking that you’ve got to see this freedom that we have and that we feel. I wanted to make a song to that, and that made me want to make that book. And so I just found myself thinking about the enormous invisibility of the female life from our culture. We were living in it, but we had never seen it before—hardly ever in films or in writing. How can that be true? It’s an outrage. I wrote the chapter that’s about a gang rape; it came really late in the writing of the book. Because once I realized I was making this book and it was almost ready to be shown to people, I thought no female life can be written without telling the story of a gang rape. It has to be in there, it has to be known that that’s also what it’s like to be a woman. There’s always the hideous potential that the very thing that you are can potentially be taken away from you. I guess I mean your possibility, your sexual integrity, your right. On some level everything you ever hear about being female is mediated by the potential of the absolute destruction of self through rape, through sexual violence. It’s part of the genetic makeup of being female. Women aren’t physically afraid of men; women are genetically afraid of men. It’s happened for such a long time. Who would we be if that could ever stop? Already I think people are feeling we’ve heard a little too much about rape. But can we ever? It’s really crucial to the whole in a way.

FITZGERALD: I feel like the big secret to Chelsea Girls is it’s really a great Massachusetts book, even more than its wonderful and crucial ties to New York City.

MYLES: Yeah, people love that reductive thing: Inferno is a great New York book, Chelsea Girls is a great New York book. But New York is almost an afterlife. The life is Massachusetts and childhood and the alcoholic family and the obsession with fashion in high school. And you actually come to New York to preserve it, because this is a big recording studio, New York. Coming to this place, this urban place, and becoming one of these eternal artists, living in this eternal presence of the artist, which is the ideal childhood you were not allowed to have, so much of the myth of being the young artist in New York City is about reclaiming your own childhood. It was for me. Because in childhood, in the childhood of this book, it really wasn’t childhood. Think about what children have seen historically, they’ve seen adults be monsters, they’ve seen violence, so it’s sort of like the adult present of the book exists so that the other invisible stuff can be rescued and brought into the present too. I always think of childhood as the inarticulate moment, and you have your little camera. You were filming it, recording it, you just didn’t know how to speak it.

FITZGERALD: Let’s talk about your upcoming work for Transparent, season two. There’s a character modeled after you, whose friend and colleague you play, and finally your “pussy poem” [“I always put my pussy …” from Myles’ 1995 collection Maxfield Parrish, included in I Must Be Living Twice] gets some sweet screen time.

MYLES: I’m in three episodes of the next season, and they’re using two poems of mine, but I really love being in the guts of it. My friends who are writing the show are amazing. Ali Liebegott is a great poet and fiction writer. Jill Soloway is amazing. I loved watching Jill direct, because I felt like I was watching a woman writing in reality. It was like watching the narrative be constructed, literally watching her say, “No, I would get rid of that paragraph, but I’d like these characters to move over there,” or “I’ll have this happen slower.” So now my comprehension of what an actual TV show is or an actual film is, is already different.

FITZGERALD: Do you see yourself ever writing for film or TV? Deleting a stanza sure sounds easier than reshooting a scene ten times.

MYLES: Oh, totally. I’m thinking I might start working on something this spring. It seems pretty organic. I think poets are supposed to be writing for television and film. I grew up in the day of early TV that was so raw and funny, and I think we’re in the next important moment of television, where it’s really telling the epic of the culture like Charles Dickens was doing in the 19th century with his serialized novels. He was feeding the crowd. Who doesn’t want to do that now? It’s amazing to be looking at this new moment close up and seeing people I know making it, writing it. So yes, I like the idea of being one of those people; it does seem like the poet’s job too. Like, a poet could have that dream, is having that dream.

FITZGERALD: You seem to think it’s obvious a show could/should revolve around a poet’s own life. Like, in the way, Louis C.K. does in Louie—those great, banal flashbacks spliced into his existence. I watch and think, “Hey, that’s Eileen’s poetry!”

MYLES: I walked into Veselka in 1975 and met Paul Violi [the late New York poet], and he said, “You should come to my workshop in October at St. Mark’s Church.” I did, and suddenly the rest of my history came out of that accidental moment. I met Allen Ginsberg, and I thought I must be in the right place. Every situation spawns another one, and those were the ones that I had, the lives I had. I mean, I wonder, would I have transitioned from female to male if I was 30 years younger? Possibly. But if I had been born even 30 years later, because it seems like the technology will only get better, it seems like one might not ever need to settle down at all. I’m reading a draft of a novel by a writer named Andrea Lawlor, about somebody who just keeps changing sexes. Samuel R. Delany wrote something similar 30 years ago, but now it seems feasible. I think the only thing I find myself thinking in relation to everything we’re saying about poetry and publicity is that at the most literal level, poetry is my politics. It’s an opportunity that gives me a way to speak.

FITZGERALD: Well, it all seems about time for you, finally, literally and figuratively.

MYLES: It’s totally about time. It used to be the beatnik was like the Jughead character, the Maynard G. Krebs character, the joker—and it’s still sort of like that today—but I think that it should be more like a kind of royalty. The poet is like the wise fool or like a version of the stand-up, because we’re standing, we’re doing stand-up. That’s exactly what we’re doing.

ADAM FITZGERALD IS A NEW YORK-BASED POET. HIS SECOND BOOK OF POEMS, GEORGE WASHINGTON, WILL BE PUBLISHED IN THE FALL OF 2016 BY LIVERLIGHT.