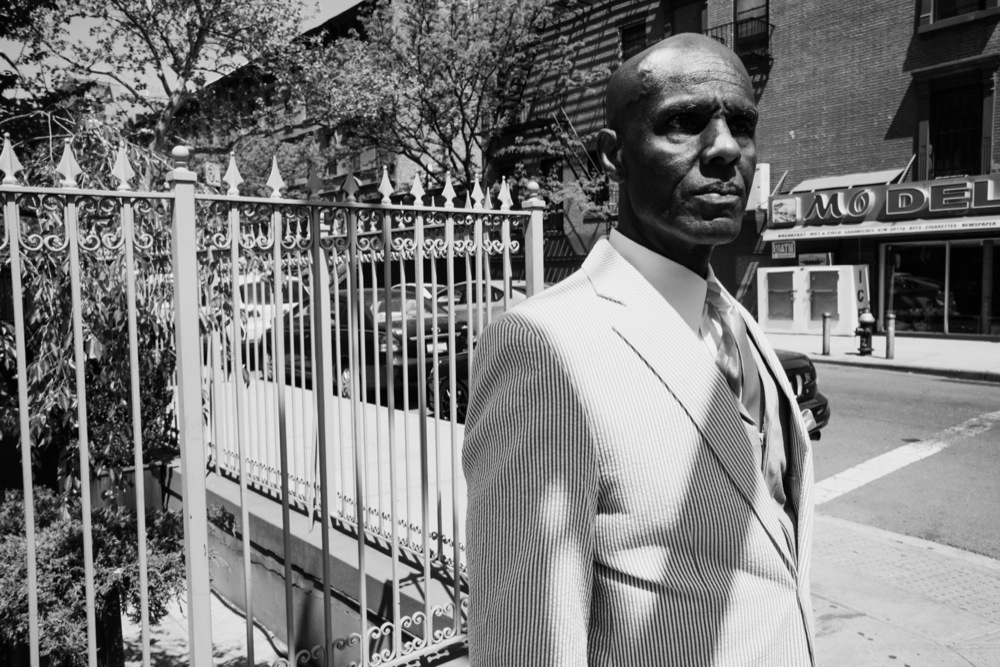

Uptown Legend

ABOVE: (CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT) DAPPER DAN AT STREET BIRD IN HARLEM, MAY 2015. THE “ALPO” COAT. DAPPER DAN IN HARLEM, MAY 2015. A VEST FOR FLOYD MAYWEATHER. PHOTOS BY SHAWN BRACKBILL.

If you saw a hip-hop artist or athlete wearing some unusual Gucci or Louis Vuitton in the 1980s, it was probably a Dapper Dan original. Using silk-screen printing, the Harlem-based designer made customized logo-printed clothing, car interiors, and furniture upholstery for the likes of Mike Tyson, Salt-N-Pepa, Bobby Brown, Eric B. & Rakim, and LL Cool J (as well as the flyest gangsters of the day), before getting shut down by a Fendi lawsuit and going underground in the early ’90s. In Sacha Jenkins’s new documentary, Fresh Dressed, out this week, Dapper Dan remembers some of his most famous designs and customers. Still based in Harlem, Dap is currently working on his memoir, and still outfits a few loyal customers, like Floyd Mayweather.

ON HARLEM: My father was born 35 years after emancipation proclamation in 1898. His father was born a slave and later freed. My father came to Harlem by himself in 1910—he was 12 years old. I spent my whole life in Harlem. It makes me feel blessed that I was part of that first generation born here. I read a study when I was in prep school about the process of “urban renewal, negro removal,” by Constance Baker Motley, who was the first black female borough president of Manhattan. I was writing for a student newspaper called 40 Acres and a Mule—Spike Lee was still in junior high school then. I did an article and used a picture of the State Office Building, which was the first building that they were going to put in Harlem to trigger gentrification. I made that building look like a Trojan horse. That concept stayed with me. I thought, “If I ever get me some money, I’m going to make sure I’m here.”

ON THE POWER OF FASHION: Fashion came by way of being deprived. I grew up prior to the drug epidemic that devastated Harlem—it made such a profound difference in the way people looked at themselves. When I was growing up, you did not come on 125th Street if you were not dressed. You would be embarrassed. Everything I had was hand-me-down from Goodwill. We were so poor that when we got holes in our shoes, we’d put paper in. Then we got very innovative and started putting linoleum in. I never had clothes, so it became a big thing to me. Clothes had this huge value to us. Clothes could make you feel like somebody.

ON LEARNING TO SHOP: My first new wardrobe came out of Alexander’s department store on 58th Street and Third Avenue, and all of it was File 13—you took a bag and zoop, you were out. You used to be able to pawn shoes and shirts and things like that, so I would buy the pawn tickets from the older guys. When I started getting money, the stores to go to were where the whole Rat Pack went: Leighton’s of New York, Cy Martin’s, House of Cromwell. These stores were so important.

ON THE DRUG EPIDEMIC: The drug epidemic came like a thief in the night. We never knew the devastating impact it would have. Did I get caught up in it? Maybe from 19 to 21. I was fortunate enough that I did a lot of reading, and I decided to go back to school. I got arrested for selling drugs June 19th, 1967, and I got out September 27th, 1967. When I was in there, one of the assassins of Malcolm X was in there, and he was on my floor. I saw the attention that he got, and I made up my mind, “I don’t care about going to prison again, but I will never, ever go under these circumstances.” I began to read a lot of political stuff. [By] 1968, I became highly culturally conscious of my history—James Brown was saying, “I’m black and I’m proud,” Martin Luther King was going on. Black consciousness hit me. I went to Africa and went to school. I got a GED, but in the ’60s, you couldn’t go to college with a GED. The Urban League sent me to this prep school for two years—this is when I was writing for 40 Acres and a Mule—and then I was accepted with a scholarship to Iona [College in New Rochelle].

ON THE ORIGINS OF DAPPER DAN OF HARLEM: When I left the streets in ’68, ’69, it stayed on my mind to wean myself away from that subculture of the streets. I went to Africa again. I decided to open up a store, thinking I could go and buy and sell to my community. But it didn’t work out that way. All the manufacturers that were popular wouldn’t sell to me. There were these young Jewish guys—the Jewish people played such a huge role in my life—who were just starting up. Their father owned a fur factory; their uncle was Fred the Furrier, who had all the fur stores in Alexander’s department stores at the time. So I went to them when they were just starting, and they were selling these jackets to me: real soft lamb leather with a possum lining. But then AJ Lester’s, which was the most popular store in Harlem, was selling the same jackets and getting them from the same person. AJ Lester’s was selling them for $1,200—we were both paying $400—and I was selling them for $800. One of my customers bought one from me and told his friend, and his friend got upset, because he paid $1,200. He went over there and pitched a bitch at AJ Lester’s, so AJ Lester’s sent somebody over to my store to see what was going on, and that person went back and told the manufacturer, so when I went down there to purchase again, they said, “Listen, man. We can’t sell to you. AJ Lester’s got five stores; you’ve only got one store. They’re bitching about your prices. The only way I can sell to you now is if you take the label out.” You know how important labels are. I got upset, and having been in Africa making my own clothes, I said, you know what, I’m going to get me some tailors. It just mushroomed and I started making my own clothes to sell. The answer came out of Africa.

ON DESIGNER “KNOCK-UPS”: One day a customer came in with a little bag and everyone was really excited about that bag. I said, “If the customers are excited about a little bag, imagine if they had a jacket.” I opened up in ’82, and this was probably ’83, ’84. First I would take little garment bags and cut them up, but that wouldn’t suffice for complete garments. So I said, “I have to figure out how to print this on fabric and leather.” I went through trial and error. I didn’t even know we were messing with dangerous chemicals—the U.S. government eventually outlawed the chemicals I was using. We made these huge silk screens so I could do a whole garment. A Jewish friend of mine helped me science out the secret behind the ink, and that was it.

FIRST HIGH-PROFILE CUSTOMERS: Gangsters. That’s who I grew up with. Middle-class blacks couldn’t accept what I was doing—you had to be of a revolutionary spirit. Who would be more like that than gangsters? And who would have the money? Hip-hop artists didn’t have any money. They used to wait until the gangsters left the store before they could come in and ask what the gangsters wore. Everybody follows the gangsters. The athletes came before the hip-hop artists. Mark Jackson, Walter Berry. I’ve got pictures of NBA players that I can’t even remember their names. The athletes had money earlier that the hip-hop artists.

FAVORITE CREATION: The “Alpo Coat” [for drug dealer Alberto Martinez] and the Diane Dixon coat [for Olympic athlete Diane Dixon].

CLOSING THE STORE: The silk screens were confiscated thanks to the legwork of Chief Justice Sotomayor. What happened was so devastating. Sotomayor was the lawyer at the time for Fendi. She’s genuine. When she raided the store, at the time it wasn’t serious. Even today they’re not that active in prosecuting trademarks, but they were even lighter back then. Court started at nine am, and we went to court before nine. The judge said, go to the lawyer’s office and do a stipulation. I go with a tape recorder with this militant attitude. The lawyers are saying, “We can talk about this.” And I said, “No, we’re going to do it this way.” I had it my way. I had a store on 125th Street, I had a factory on 120th Street, I had a huge number of workers, and I lost everything. [If I’d taken the stipulation], the most I would’ve paid would be a $5,000 fine, but by me not listening and not wanting to compromise with the lawyers, that was that.

GOING UNDERGROUND: You might have seen this promo I did for the movie The Most Violent Year (2014). You might’ve heard me make a statement in which I said, “You can’t be in it and not of it.” I was in the midst of this subculture, but I was of the problems of that subculture. You can’t think that you’re going to be on the perimeters and be alright. One night they tried to kidnap me and I got shot in the back. The bullet traveled inside the base of my neck. All of that happened around the same time, so I took it as an omen that it was time for me to move on and do other things.

ON FAME AND THE DAPPER DAN REVIVAL: I was never into that. I stayed in the back of the store and people didn’t even know what I looked like—that’s why it was so easy for me to go underground. I was never in it for the glamour. My son made me come out from the underground. I never thought nobody was even interested in my story. My son said, “Dad, people want to know about you.” So I did the thing for Jay Z, and all these people started calling. When people come to interview me, I interview them because I’m still not quite sure, “What are you doing here?” I’m not used to all this yet.

FRESH DRESSED COMES OUT FRIDAY, JUNE 26. FOR MORE ON DAPPER DAN, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.