IN CONVERSATION

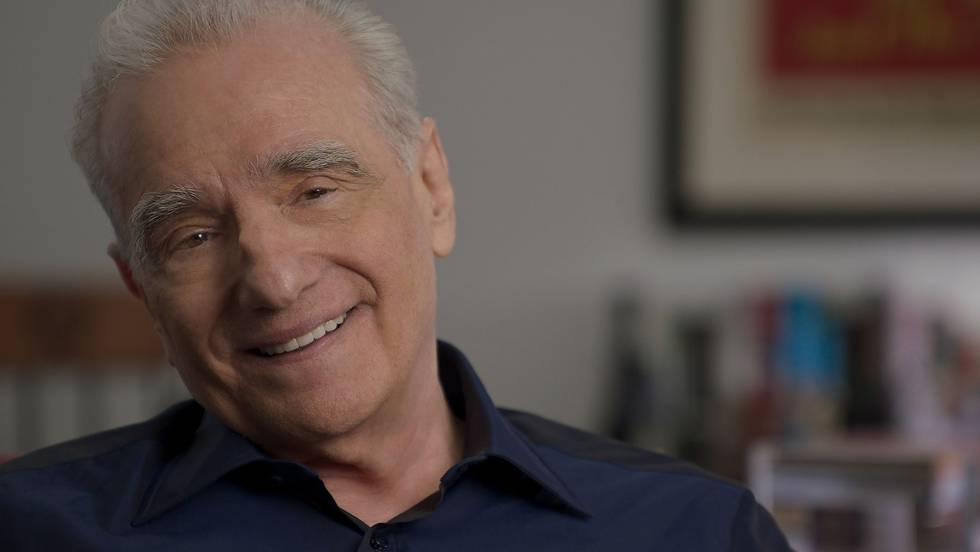

Rebecca Miller Tells Jodie Foster How She Got Inside Martin Scorsese’s Head

When the director Rebecca Miller first met Martin Scorsese on the set of Gangs of New York, she sensed there was a storm brewing just under the surface of one of America’s greatest filmmakers. “You could tell he was so thrilled and so scared and so alive,” she told us last month. At the time, the director of Maggie’s Plan and The Ballad of Jack and Rose, who happens to be married to Daniel Day-Lewis, didn’t yet know she’d one day take up Scorsese and his towering oeuvre as her subject. But when she set out to make Mr. Scorsese, her new five-part Apple TV docuseries, the 63-year-old filmmaker was determined to go beyond the movies and craft a portrait of an artist at once fragile, brilliant, temperamental, and tortured. To explain how she did it, she got on a call last month with an actor who knows Scorsese as well as anyone, the great Jodie Foster.

———

REBECCA MILLER: Oh, my god. I’m just spilling everything all over myself. I’m drinking juice out of the only glass I could find, which is a cocktail glass. [Laughs]

JODIE FOSTER: It looks very elegant. So I finally got to see everything. It’s so good, and it’s kind of frustrating because you just want more and more.

MILLER: Thank you. Yeah, it’s like you want his entire life in there but the particular film that I made shows how his life and work are kind of in tango. And if you run off too far and start listing more works, it loses its kinetic energy.

FOSTER: He’s just such a compelling protagonist. Of course, he’s fun and he’s funny and has all this energy, but there’s such depth and such vulnerability to him, and he’s so willing. Did that take work or is that just how he came to the table?

MILLER: I think he decided to be open before he got there. I mean, we had a relationship in the sense that he had watched my movies. When I met him during Gangs of New York, I was about to make Personal Velocity. I was terrified because we had $2 to make the movie and I knew I was going to use a lot of voiceover. So I said, “Can you recommend, apart from your own films, voiceover films for me to look at?” And of course, he gave me this long list. And then he watched a few other movies I made and he had also read my books. So by the time I asked him, he kind of knew me, because if you watch my movies, you know me really well. So there was a level of trust. And I think he was ready. He had said no a lot, because I think saying yes to this movie was a little bit like the whiff of death. Like, okay, I’m going to be summed up now, and no one wants that—not death, but closure.

FOSTER: Did you guys talk about the structure or where you were headed together? Did he see the footage?

MILLER: He did say a few times, “I don’t know what you’re doing.” I offered him to watch it about a year before I was finished, but he just wanted an elaborate transcript. He had a few informational notes on that. And then he comes back after I’ve done all these interviews and says, “I just realized something. You asked me back when we started if my father was humiliated.” Because I’m very attuned to father’s humiliation for various reasons. I saw my father humiliated. And so he said, “You asked me that. And I sort of said yeah, but I didn’t really elaborate. And then I remember that when I saw Bicycle Thieves, I was suddenly hit by the expulsion from Corona and being sort of laughed at by people as we put our belongings on a U-Haul.” Anyway, so I didn’t really talk to him about what we were doing because he didn’t want to watch it. And then I sent it to him and I was like, “Okay, now we’re locked…”

FOSTER: What a time to send it to him. You’re already locked and you can’t pull anything apart.

MILLER: I mean, I did send it to them, but then he never watched it, and then we just kept going. And then when he finally did watch it, he had a couple informational notes. So we went back in and we changed those things. But he accepted the form of it, and he accepted the honesty of it. There was not him saying, “Wait a second…” because that would’ve been a real disaster.

FOSTER: Right. Watching your life in a movie that allows you to access something so meaningful.

MILLER: Yeah, I think it was quite painful for him to watch the whole film because he had to relive all this stuff. I was telling him who I was interviewing and I said, “If there’s somebody that you really don’t want me to talk to, just tell me.”

FOSTER: What were the big surprises?

MILLER: I mean, I was constantly being surprised. Part of it was I really didn’t know very much about his life. I had studied the films and was ready with my questions. I knew he had asthma, I knew that there was some kind of problem with drugs, but I let myself learn about him by talking to him, so I was genuinely asking questions rather than trying to get something out of him. I mean, the level of suffering, I think, really surprised me, how completely he threw himself into his life and really almost gave up a couple of times, really for film. It’s like life, film, love, all mushed up together. I found it very moving. And he’s still not careful with himself.

FOSTER: In that he commits to everything?

MILLER: To the films, but also to life. Because directors like to be in control, and he does control things, but the way he lived—at least in the ’70s—was not as somebody who’s completely in control. And also the way that he tossed himself into his life. I found him to be really honest with himself. I think we make ourselves out to be maybe a little better than we are in our heads. But I don’t think he does that.

FOSTER: Well, one thing I was struck by was the number of times he kept going back to, “This one was a dud and I thought this was all over.” We look at his movie career as one treasure after another, so it’s hard to hear him consider his movies as failures. Like, what do you mean that New York, New York was a failure? It doesn’t work in a lot of ways, but it’s an extraordinary movie.

MILLER: I mean, it’s so hurtful when somebody doesn’t like your work. It feels so personal. But he’s able to appreciate the value of the work while holding some part of what that criticism felt like. I think those two things can co-exist.

FOSTER: Yeah. It was interesting to see how delighted he is going back to the memories of certain things, like Kundun, for example. I was just so struck by how soft and sweet and gentle he was. And The Last Temptation of Christ, talking about that experience. It’s like he puts himself into the moment. And I remember that about him as a director. We didn’t have video assist or anything in those days so he’d just sit under the camera, and even though he did so many takes and went through so much film, on every take he’d have to hold his mouth because he couldn’t stop laughing. You’re like, “But we’re doing the same dialogue!” We’d do 10 takes, and he’d still be in the moment.

MILLER: He’s such a compelling protagonist, just like the larger-than-life people who raised him, like his mother. She was a massive character and the people that he grew up with, those neighborhood guys, were all really natural performers.

FOSTER: Totally. So you did the documentary about your dad [Arthur Miller]. Was that the first documentary you’d ever done?

MILLER: Yeah.

FOSTER: That’s interesting that you were pulled back into something like this.

MILLER: I know, I do have an interest in artists and how they work, and a sympathy and a protectiveness, I suppose.

FOSTER: Yeah. The whole reason I continue acting is really so I can learn from other directors. And the directors that have taught me the most, and that I admired the most, really went into detail. Somebody like David Fincher, for example—everything has to be perfect, he knows everyone’s job better than they do, and it’s all orchestrated in his head long before he ever comes to camera. I loved working with him, but I am absolutely not like that. And yet I learned so much from him.

MILLER: I totally understand that. I’ve just learned so much from this process, and I don’t even know how to articulate it. It’s almost like I took this bath for five years in it, and I’m drying myself off. I’m trying to figure out what I’ve absorbed.

FOSTER: What about your process? I mean, when we knew each other in college, I guess we should say that on the record.

MILLER: We had French class together.

FOSTER: And we took a Freud and Lacan class that was super amazing, actually.

MILLER: Did you do comp lit?

FOSTER: I just did the literature major.

MILLER: All the smart people did that. I was just a painter.

FOSTER: You’ve been all over the place. I remember Angela as a very painterly movie. It’s really tonal.

MILLER: Yeah, there was definitely a bridge between making images and telling stories. I was a late bloomer because I grew up around adults all the time. And I think with Angela it was almost like I was making it as half a child. It’s hard to describe. I was so naive. Because I would have never made that movie if I wasn’t, and I’m glad I did.

FOSTER: It’s actually really funny watching Scorsese examine his early work. I’m always sensitive to Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore because that’s the movie that I wish I’d made. I love that film.

MILLER: I love that film.

FOSTER: It’s the only one that features a woman, really. And he got dragged into that. He didn’t really want to do it. It was a really great script by a very, very good writer. And he was always like, “Oh, but it’s not my thing.” And you can see the Harvey Keitel scene was like, “I can do my thing.” And so he brought Harvey in to play that part where he suddenly became this really nice guy that’s kind of like a cowboy. And then in an instant, he turns into this violent, horrible guy who punches through the door and grabs her by the hair and this incredible violence bursts on the screen. And I remember feeling like, “Oh, well, at least he got his moment to do what he does.” And the rest of the movie, I think he always felt a little bit like he was poorly cast and almost like he appreciated the movie but was embarrassed to have done it because it’s not who he is.

MILLER: What I thought was remarkable about the movie, despite the fact that it wasn’t natural to him, was how he tried to get into the point of view of that person. And he succeeded. I do think that he put a bit of his mother and him in the movie, that relationship, that teasing intimacy.

FOSTER: In your career as an artist and you just do stuff. You don’t know why you do it, but then there comes a moment where you look back and go, “Oh, is there a pattern here?” And it’s fun watching him grapple with his pattern and almost be uncomfortable with some of his early choices. Of course, he wouldn’t be who he is if he hadn’t gone through all of that.

MILLER: Well, even Vesuvius VI, which is the story which takes place on the roofs where they’re all wearing sheets…

FOSTER: Oh, yeah. Right. With the togas.

MILLER: He was so worried about that because he still cares. It’s juvenilia, but it’s still his film. He was like, “Please don’t use that shot. Use that shot.” His criticism was still extending to even his 16-year-old self.

FOSTER: I’m sure you look back now after two documentaries, and Maggie’s Plan, which is very different than anything else you’d ever done before. Do you see your pattern?

MILLER: It’s funny, I make movies in twos, I’ve figured out. Angela and The Ballad of Jack and Rose went together. They were both full of nostalgia and wistfulness and a kind of real sadness, but they’re also kind of lyrical. And then Personal Velocity and Pippa both go in and out of the past all the time and use a lot of voiceover, so they’re really formally quite similar. And then Maggie’s Plan and She Came to Me are both attempting to play with the genre of romantic comedy. There’s a part of me that’s quite like that, too.

FOSTER: And you did your twos with the two documentaries.

MILLER:Yeah, I did my two documentaries of these two great male artists.

FOSTER: Yeah. And they are great men. Of course, as women directors, we had options, but we just didn’t have the same options. Our paths were always going to be different. But to be a great man, what does that take? I kept finding myself wanting to talk to Marty through the screen while I was watching the film and say to him, “Don’t sweat it. You’re going to have this huge body of work.” And it’s not that I didn’t want him to care so much, it’s that I just didn’t want him to take it personally.

MILLER: Absolutely. When I first met him on Gangs of New York, he was setting up the shots for that big first battle scene where Daniel [Day-Lewis, Miller’s husband] comes out and says, “By my challenge.” You could tell he was so thrilled and so scared and so alive. And I thought, “Wait a minute, this is the maestro. Why is he so edgy?” And I think a little bit of that is what keeps him in it, otherwise he would just sort of stop. He needs to care, he needs to still be hurt so that he doesn’t just relax. But he does seem more at peace.

FOSTER: Yes. Spike Lee is in the movie as well, but he has the same thing. He tortures himself and everyone by, for example, being incredibly impatient. So he’s on set and he’s really worried about getting his day, he’s worried about it not happening correctly. He’s just tearing his hair out. And you want to say to him, “Everything’s going all right, why are you torturing yourself?” But I think that’s a part of the process. It’s a kind of like you have to have that anxiety or it doesn’t feel real.

MILLER: Yeah. Isabella Rossellini said it so well when she’s talking about his anger, that towering rage he would go into when they were together. And she talks about how him being that boy from Little Italy, how the anger was something that armed him and got him ready for his day and to able to control these great hordes of people. And then realizing now perhaps that he’s not served by it anymore. I was talking to Elvis Mitchell today and he was saying that he didn’t think that Scorsese characters really change that much throughout the films, that they’re really who they were when they started. But in this film, you see Martin kind of change.

FOSTER: Well, I guess part of his philosophy was that those guys weren’t going to change, that that was sort of their destiny and that they didn’t have the arcs that we’re used to in film where somebody comes to understand themselves. These guys were never going to understand themselves. They’re not the kind of guys that you could sit them down on the couch and say, “You really hurt my feelings,” and suddenly they would scratch their heads and go, “Oh, wow, I guess I did. I’m going to take accountability.” They were not conscious heroes; they were unconscious heroes. And part of his journey was just, “I’ve got to capture this and I am not going to judge it or force them to wake up.”

MILLER: That’s so brilliant. And it’s actually what you said a little bit in the film about how moral closure was never what he wanted. He leaves it open-ended. It’s part of why his films don’t feel dated. It’s a refusal. But it is terrifying looking back and sculpting somebody’s life, every cut you make is expressing something quite differently. And that power can be unnerving.

FOSTER: Yeah. Because it’ll have a lot of impact on his life and his legacy.

MILLER: And wanting to be fair and clear-eyed, because I really came to love him. Actually, I really came to have immense affection for him over the years, that I felt I could trust that my love would come through, that you would feel it. Because I really do strongly believe that filmmakers feeling one way or the other is always communicated.

FOSTER: Yeah. And that’s what you get from Marty when you see his movies, this deep love and affection for these people, people who are violent and make huge mistakes. Even The King of Comedy, which has this weird, dark, satirical style to it, there’s so much love in that movie for that character. And that’s the part that must be painful, I suppose, that he’s always loved them too.

MILLER: That to me is the very center of his work. The key is that he loves them.

FOSTER: Absolutely. Well, I feel very honored. I can’t believe that I got to be somehow affiliated with the greatest filmmaker America has ever seen. I am not sure how that happened, but I’m super grateful.

MILLER: Well, it’s these serendipitous things. It’s like Marty meeting De Niro. So when you come to New York, will you tell me?

FOSTER: Yeah. Come over. We’ll have dinner at our house.

MILLER: I would love it, truly. Okay. Goodnight.

FOSTER: Take care, Rebecca.