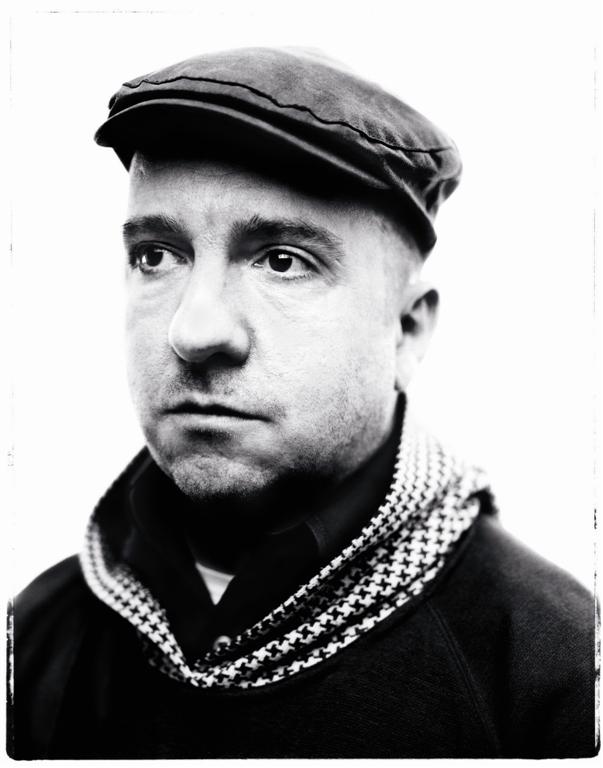

Stephin Merritt

Stephin Merritt is one of America’s most original and distinctive singer-songwriters. He has contributed music to soundtracks, works of musical theater, and television commercials, but he remains best known as the main singer and songwriter of the band the Magnetic Fields. Famous for its use of such instruments as the ukulele, banjo, and Marxophone, the group will release a vinyl version this month of its classic album, The Charm of the Highway Strip (1994). Merritt got on the phone recently with filmmaker Guy Maddin, who shares, among other things, Merritt’s love of silent movies.

Guy Maddin: It’s been a dream of mine to appear in the pages of Interview magazine for kind of a long time—a kind of secret, narcissistic dream, and so here I am.

Stephin Merritt: The last time that I was in Interview magazine, as far as I remember, it was a full-page photo of me standing in front of a purple wall on St.Marks Place. I was wearing a dark sweater, and my nose is bright red because they said that since the picture was running in the April issue, I had to not be wearing winter clothes, even though they were shooting in December and it was down around zero degrees Fahrenheit.

GM: Your body was probably changing in all sorts of ways.

SM: Terrible, yes.

GM: A light chastisement to the Photoshopping department at Interview.

SM: Well, there was probably no Photoshopping department at the time: It was 1995. Now, thank heavens, everything is Photoshopped.

GM: It’s hard to reduce someone’s work to one or two words, but what gives me the goose bumps when I’m listening to you is just how honest you are. You arrive at that honestly—

SM: Dishonestly.

GM: —by the most dishonest tricks possible. [laughs] It’s something I’ve always respected in my favorite writers and painters. Songwriters, and of course filmmakers, try to cobble and steal to come up with their own form of honesty. So I commend you.

SM: By a coincidence, two weeks ago I was listening to your commentary on the DVD of Cowards Bend the Knee [2003], and there was so much autobiography in your commentary. I had no idea that the movie actually had to do with your life.

GM: I’m not too sure if I have a very smart approach to revealing my life. Luckily, I doubt if many people really care about my life that much. But it was really liberating.

SM: Why would anyone want to present their own life in some realistic way?

GM: I wasn’t too sure. I’m scared of even the word “realistic.” I felt the need to blurt out my emotional autobiography. Maybe just because I thought that by being so ridiculously honest, no one would believe me. Autobiography just gives you license to be mischievous and tell the truth. I think I remember reading your saying somewhere that singer-songwriters are often confused with their singing-voice personas. How do you feel about that?

SM: I feel that if I have something to say about my own life, it’s so generic that it could basically apply to almost anyone’s life anyway. The emotional contact would be all that I would really have an urge to express. When you’re making a singular pop song, you don’t really need any subject matter. You just sort of say, “Uh, I love you.” And then you try to figure out some rhyme for that, and there never is one.

GM: [laughs] I’d been listening to you long before I ever even knew what you looked like or what your instruments looked like or how you cradled a ukulele. Long before YouTube. Anyway, enough of that. I wanted to talk about how we present ourselves in public some more. The first acting role I ever took on in a film was in drag. I wasn’t playing a drag queen or a tranny. The only part left in a friend’s film was a female part, and I really wanted to be an actor so badly in those days that I said I’d do anything, basically, to play the part. And he actually let me play it as a woman.

SM: Was it a speaking role?

GM: It was a speaking role. The trouble is that I’m a bad actor. I was younger then and perhaps plausible as a plain woman. The most discouraging thing wasn’t the fact that playing a woman gave me body-dysmorphic disorder but that I was just such a bad actress. So I have retired from that. [laughs] From now on, I’m only hiring people to play me.

SM: I wish I could do that as a singer.

GM: I know you do DJ-ing gigs now and then.

SM: Mm-hmm.

GM: What kind of evening could we expect from you at the turntables?

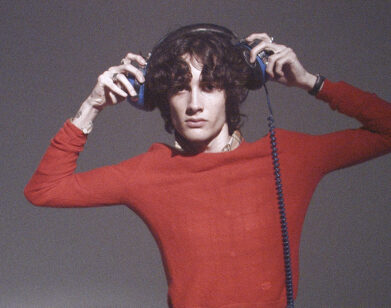

SM: Well, I play bubblegum psychedelic music from the mid-’60s to the early ’70s.

GM: What do you think of the Archies?

SM: I adore the Archies.

GM: Did I dream this or was there not an expression on an old TV show that I haven’t seen since I was a kid: “Everything’s Archie.”

SM: They had an album with that title. “Everything’s Archie”—like, “It’s all a drag.”

GM: When you got your music used on Volvo commercials, that must have felt pretty good.

“I call my GPS system ‘Vera.’ She sounds like an elderly British woman.”Stephin Merrit

SM: I sort of believe in Volvo in a way that I probably shouldn’t, but I owned a Volvo for five years and only gave it up to my manager when I didn’t need a car at all anymore. I think Volvo is basically the safest car in the world. So I was totally happy to be identified with it.

GM: Volvo loyalty was pretty famous in the days long before Mac loyalty. As far as I know—but I haven’t done my research on this—there’s nothing politically touchy about being loyal to Volvo. [laughs]

SM: No—they’re Swedish! Now I have an ad campaign where I’m singing about sugar-free chewing gum. It was too Archies to pass up. I couldn’t really live down refusing a chewing gum commercial. I was the voice of Orbit, Extra and Eclipse.

GM: I can hardly wait to check that out.

SM: I got to invent the phrase, “Chew not on chocolate-chili chips, chew Orbit, Extra and Eclipse.” Ever since I invented this chocolate-chili chips idea, I’ve really wanted some. I feel like I have created the demand. There’s a commercial out there that millions of people are seeing, which is telling them not to eat chocolate-chili chips.

GM: Stephin, you’re like the first person I’ve ever interviewed, so I don’t know how to continue.

SM: It’s important to leave out anything too revealing, like your social security number or your address.

GM: If you feel yourself getting too close, I can drop my pants and, as a distraction, you can pull yours up. [laughs]

SM: I’m pulling mine up, but nothing is really happening. [laughs] So let’s move on: I have been reading Isadora Duncan’s book My Life. It cuts off when she goes to Russia, but it’s really a great, astoundingly odd book. I have been visualizing it basically as one of your movies.

GM: Really?

SM: I see her probably played by a boy. But definitely in black-and-white, probably shot in Super 8. And she does all this dancing—literally dancing down the street. Often in Athens.

GM: This is really uncanny. I’ve been thinking of her so much lately. I’ve wanted to do a dance film that doesn’t necessarily have dance in it wall-to-wall—where all the movement of the actors is choreographed from start to finish. So people move when they’re not dancing with the intent of dance. I also wanted to have a score written before the movie, or at least simultaneously with the movie. These are all sort of parts of an unwritten-down manifesto, but Isadora Duncan of course came to mind, possibly because of the era in which she was flapping her scarf behind her. Also because of the raw sexual energy that seems to explode out of the very idea of her.

SM: Well, if you keep her title, My Life, then you can keep going with your autobiographical work.

GM: And just cast myself as the creator of modern dance?

SM: Uh-huh.

GM: I love it! Are you hearing any Stephin Merritt melodies?

SM: Oh, yes. If you wanted to do it as a musical or even as a heavily smart thing, then I am available.

GM: Is there anything else we should cover? I feel I haven’t drawn any confessions out of you. We should mention that you’re rereleasing your Highway album.

SM: We’re doing a vinyl version of The Charm of the Highway Strip, and then we’re doing a vinyl version of Get Lost. We’re talking about a vinyl version of 69 Love Songs. When I get back to L.A. in a few days, I will be listening to the new master of a vinyl version of Distortion.

GM: These are really exciting birthing times for you—or re-birthing.

SM: Yeah.

GM: You’ve moved from New York to L.A. Everything’s been cool there?

SM: I like riding around in my little red Mini Cooper. With a GPS system, because I don’t know how to get anywhere. I call my GPS system “Vera.” She sounds like an elderly British woman. A stern elderly British woman.

GM: And your Chihuahua?

SM: Irving.

GM: Does Irving ride shotgun?

SM: He likes to stick his nose out the tiny little window of the tiny little Mini Cooper.

GM: I suggest a doily for his hind paws.

SM: That would be good. He gets the car very dirty, usually.

GM: I remember my friend Isabella Rossellini told me that she once had a pet pig. It was really cute when it was little, but when it grew up, I guess she didn’t bother getting it fixed. So every night she would say good night to Spanky and go to bed. Then she’d get up in the morning and Spanky would have raped all the furniture and moved it all around and slimed it up but good.

SM: Nice.