St. Vincent

I might rather go see GWAR spray fake blood on an audience than go see another person with an acoustic guitar baring their soul. Annie Clark

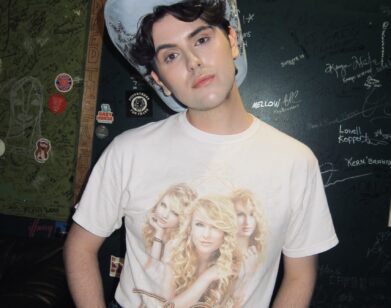

There is something wonderfully contradictory about Annie Clark, the 31-year-old musician who performs under the moniker St. Vincent. She was often depicted as a kind of gamine chanteuse on her early album covers—all big eyes, soft curls, and porcelain skin—her music typically eschews any kind of twee sweetness in favor of unexpected guitar shreds and fanciful composition. Her most beautiful songs function as veiled expressions of confusion or outright rage (“Desperate don’t look good on you / Neither does your virtue / Paint the black hole blacker,” goes a verse from 2009’s “The Strangers”). In fact, many of Clark’s best songs seem to articulate the feelings of characters that have been thrust into a role for which they were not made. The video for “Cruel,” from St. Vincent’s critically lauded 2011 album, Strange Mercy, features Clark being kidnapped by a family and forced unhappily into the role of motherhood before eventually finding herself buried alive. As for Clark herself, she seems increasingly at ease in her role as an artist (and, some would say, the reigning doyenne of indie rock). Over the course of three full-length albums, she has developed a devoted fan base that has even included David Byrne, with whom she collaborated on the 2012 album Love This Giant—the two artists spent the better part of a year together touring North America, Europe, and Australia.

On her latest album, St. Vincent (Loma Vista/Republic), Clark expands her sonic repertoire even further. Operating under the credo “I wanted to make a party record you could play at a funeral,” Clark ups the ante via an amped-up rhythm section and an arsenal of distorted guitars that are frequently made to sound like tweaky synthesizers. Set against the record’s more groove-based palette, Clark weaves together a series of disparate narratives both beautiful and surreal: walks in nature quickly give way to snake sightings (“Rattlesnake”), the tedium of daily life is eviscerated (“Birth in Reverse”), and technology continues to frame how we see ourselves (“Digital Witness”). For Clark, who splits her time between New York City and Texas, songwriting is key to her own personal evolution. On the cover of St. Vincent, she is no longer the ingénue. Pictured on top of a futuristic throne, the singer—now platinum-haired and metallic-gowned—has assumed the rightful position of queen.

T. COLE RACHEL: I know you were born in Oklahoma and grew up in Texas, but how did you eventually make the move to New York?

ANNIE CLARK: Well, I still kind of split my time between New York City and Texas, but most of the time I’m on the road, honestly. I always wanted to make my own music, so even when I was playing in other bands, I just looked at it like it was an apprenticeship or something. It never dawned on me one day that “I should make music myself!” because I always felt that way. That was always my plan. I never had a plan B in terms of my life or my career.

RACHEL: The past couple of years have been pretty hectic for you. You went directly from touring in support of your 2011 album, Strange Mercy, into a tour with David Byrne. At the end of all that, did you take any time off before you started working on the new record?

CLARK: I started writing songs for it about 36 hours after I got home from about a year and a half of touring. I had a year and a half of ideas and sketches that I’d been carrying around with me from the tour. I’d sometimes wake up and think of a melody that I’d sing into my phone and save for later. On tour, I’d never had time to really sit down and process anything. You know, trying to process the past two years of my life … It goes by so fast when you’re on tour and you kind of just have to be in the moment. When it finally does stop and you feel like you’ve been dropped back down to earth from the tornado, it’s like you can either get back to work and make it a really creative time or you can just lose your mind. After being on the road for so long, it’s shocking when you’re home again. Nobody is clapping for me whenever I make toast. There’s no tour manager telling me when to eat and when to get on the bus. All the structure that touring provides is suddenly gone, and it’s just you. I felt like I’d been thrust really violently back into the mundane.

RACHEL: That’s when most musicians start to get crazy and things go haywire.

CLARK: It’s true. When you are on tour, it’s like every day has this dramatic arc. You have a goal and that goal is to play a show. Everything before the show is in preparation for the show, then you have this cathartic release at the end of the day. Back home, you don’t have any of that. You go out in search of the same high you get from playing and performing, and that’s when things can go off the rails pretty quick.

RACHEL: When it comes to songwriting, do you tend to set specific parameters for yourself?

CLARK: I usually do set parameters for myself, but for this one, I felt really free and really confident. I had nearly two years’ worth of life that I’d lived and friends that I’d made and late nights out and heartbreak—I had all that stuff to write about without the need to prescribe a specific theme to it ahead of time. I think I’ve acquired a certain amount of wisdom, however fleeting it might be, in that I kind of know now that songs will just tell you what they need to be. Music will reveal itself to you, and it’s not about having some kind of grand master plan. Certainly it helps to have a certain knowledge about the architecture of how songs work and to have a certain set of skills to fall back on whenever you get stuck, but music is not really controllable. It’s bigger than your ego. That’s always helpful to realize and remember.

RACHEL: It’s a matter of engaging the process every day but also getting out of your own way.

CLARK: Absolutely. You can’t judge the process while it’s happening. That’s really the key to finishing anything. If it’s bad, who cares, just keep writing it. It’s all so subjective. There are those shows that you play and you think, “Man, I was really feeling it last night! I was there!” and you walk offstage feeling great. Then you listen to a recording of it later and think, “Woo, that was a rough one. Ouch.” And there are those shows when you feel like you just can’t get your head in the game and things are just off in some way, and then you listen back to that and it sounds a thousand times better. So I try not to put too much stake in what my own experience was of a particular moment. There is often this huge gap between the way you perceive yourself and the way you actually come across. That’s what’s so great—and sometimes so awful—about recording yourself live. You can listen back and say, “Oh, that’s what I really sound like? Let me try that again.” Recordings are a very honest mirror. Sometimes you gotta know that you don’t actually know.

RACHEL: Your audience seems to have grown by leaps and bounds with each record you’ve released. Knowing that there is this increased amount of attention focused on what you are doing—particularly in the indie-rock world—is it difficult to tune that stuff out and not let it interfere with your creative process?

CLARK: I think one of the best things about getting to grow slowly with an audience—I mean, this is my fourth record, fifth if you count the one I made with David—is that I’ve learned to just trust my instincts. That’s what has gotten me to wherever I am right now, and it would be illogical to start second-guessing my instincts now that more people are paying attention. Everybody likes success and everyone wants to be successful, but that can make you do things you might not otherwise. When you start thinking, “What if I trim off that rough edge or just try and sweeten the center a little bit so more people might like it,” it’s a very slippery slope. The best worst-case scenario is that you make something that you don’t believe in that a lot of people happen to like—then you are stuck playing something that you don’t believe in and that makes you feel ashamed of yourself while a lot of people are cheering for you. That is not something that would make me happy.

RACHEL: This record contains some of the loveliest songs you’ve ever written and also some of the funniest. The song “Rattlesnake”—in which you decide to go for a naked walk in the desert only to be chased back to civilization upon seeing a snake in your path—struck a chord with me because I once had a similar experience.

CLARK: It is a true story. Writing generally requires a certain amount of imagination, but then sometimes it requires only that you simply report the facts. “Rattlesnake” and “Prince Johnny” are good examples of that. You don’t really have to dress them up or make them sound poetic because they already are. But wait, how did you come in contact with a snake?

RACHEL: I was swimming in a pond in Oklahoma when I was a teenager.

CLARK: Why were you swimming in a pond?

RACHEL: It was just like your song. Sometimes you have this impulse to be out in nature—to take off your clothes and jump in a pond—and then 30 seconds later a snake swims right by your face.

CLARK: Water moccasin! Oh my god. No.

RACHEL: It was the very definition of flailing. I felt like I was punished for trying to have some kind of beautiful nature experience.

CLARK: Exactly! It was like, “I tried nature, and it didn’t work out.” Also, I don’t think I’ve thought about water moccasins for about 20 years or so.

RACHEL: A song like “Digital Witness” seems to address a feeling so many people have now, which is a real attraction/repulsion when it comes to the way technology dominates our lives now.

CLARK: I do have that attraction/repulsion thing. It’s because of the kinds of technology that we use every day with our laptops and stuff that I have a career. I started out recording myself on a small recording setup when I was 15 or 16, and it enabled me to sit alone in my room and record myself and make songs. I didn’t have to be in a band in order to cultivate some kind of musical vision. But we’ve obviously crossed over into this other realm where we are now totally obsessed with documenting the minutia of our lives simply because we can. Now that we know that the NSA is looking in and we’ve got the roving eye aimed on us, you just wonder how it’s changing our behavior. There’s a saying that any creature that knows it is being watched will change its behavior, and you wonder how that bodes for our future. Also, not too long ago, I judged a talent show for Rookie magazine, which was totally awesome. The majority of the audience was made up of girls, all of whom were really cool and well-dressed and they were all self-possessed in a way that I just don’t remember being as a kid. There was a girl who was a stand-up comedian and a girl who was a hula-hooper and another girl was this great yo-yo champion; it was really wonderful. At the end we had a chance to ask them all questions: How did you learn to do this? How did you become interested in this? The answer was always that they taught themselves from watching YouTube videos. So these kids who never knew a time before the internet are just going with the flow and synthesizing all this technology in a very cool way; they don’t seem to have any of the baggage that people our age do. I’m not a doomsday prognosticator in any way, but I do feel a kind of psychic drain. I feel kind of depressed by technology at times.

RACHEL: Technology seems to play a larger role on this record in other ways as well. There are more synths at play and much stranger guitar sounds. Did the sound of the record evolve naturally or was there a conscious decision to play up an electronic element?

CLARK: It happened pretty naturally, actually. A lot of things that sound like synthesizers are actually guitars. All the music is played by people; there aren’t programmed drums or anything. I wanted it to have the feel of humans but the sound of machines.

RACHEL: There is a quote in the press materials for the record in which you say that you wanted to make party music that could also be played at a funeral. You’ve always managed to play with those expectations, whether it’s a really upbeat song that, at its core, is dark or a really sad-sounding song that has uplifting lyrics.

CLARK: This time I really wanted to make a record that people could dance to. Having just come off the road with David Byrne, I was so inspired by the fact that people at the shows would get up and dance. That’s not something that usually happens. When the collective consciousness of a crowd is like, “We’re compelled enough by this music to actually move our bodies and not feel self-conscious about it,” that’s cool. As a result, I almost reverse-engineered this record to make for a good live show.

RACHEL: Are you excited to get back out on the road?

CLARK: I am. I start rehearsals tomorrow and I’m excited to step up the quality of the show. I’m working with a group of great people on sound and lighting, plus I’m working with a choreographer. Not that it will be a Beyoncé-type show—I wish—but I want to continue to try to blur the boundary between a rock show and a theater performance and a dance piece. I just really want it to be a show—a real experience. The idea of just getting up there and playing some songs is very boring to me. That just makes me think of performing at a coffee shop or something. I really want to push it. Part of my reasoning has to do with seeing so many shows myself. Even if I love the band, it really takes a lot to make me pay attention. I might rather go see GWAR spray fake blood on an audience than go see another person with an acoustic guitar baring their soul. That being said, I know this year is going to be busy and difficult, but I feel ready for it.

T.COLE RACHEL IS A BROOKLYN-BASED WRITER. HE IS WORKING ON A COLLECTION OF POEMS AND ESSAYS, TO BE COMPLETED IN THE FALL.