How POPO Made ‘Magick’

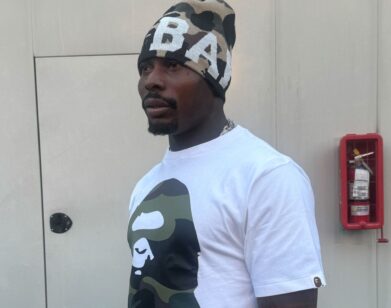

ABOVE: POPO’S ZEB MALIK. PHOTO COURTESY OF THEOPHILUS LONDON

Zeb Malik is the founding—and currently the only—member of POPO, a grunge-rock concept that sounds a bit like Joy Division doing a Bollywood soundtrack. Zeb cut his teeth as a musician touring with Nine Inch Nails, Theophilus London, and Sleigh Bells, recording with various influential producers, and even briefly working as a nursery school music teacher before the release of his first album, Dope Boy Magick. We recently sat down with Zeb to figure out how this impressive CV came about, and how it led to the release of the album.

KRISTINA BENNS: How and when did you start playing music?

ZEB MALIK: I remember playing drums in nursery school, but that was short-lived. My parents bought me a Rice Krispies drum set. The first day I got it, I went to school, and when I got back, my brothers had poked holes in all of the drums. So that was the end of that. [laughs]

Really, what started it—I got really sick when I was a kid, I got Guillain-Barré syndrome. I was walking around Pakistan and one leg got numb, the other leg got numb, eventually I couldn’t walk at all. I started getting weak to the point where I couldn’t even lift a soda bottle—the doctors there had no idea what was wrong. We came back to the United States, and I spent a month in the hospital, and after that, part of my physical therapy was working with my strength and coordination—playing drums.

BENNS: What did you do before you started playing music professionally?

MALIK: All through high school, I worked as a counselor at a performing arts summer camp. Through that network, I eventually got connected to someone that started a nursery school. She asked me if I would do an after school program, so for a year I ended up teaching a nursery school music program. It was amazing, actually! I would bring my drums in and play some stuff, and the kids would tap on it. I recorded a lot of what happened in those classes. It was very inspiring. I think I started imagining making a career out of that, but it just didn’t feel right.

BENNS: You went on tour with Nine Inch Nails when you only had a demo out; how did that happen?

MALIK: I met—and was briefly managed by—Newton Cohen, who was just a man about town in Philly; he knew a lot of musicians. He heard our music playing and he told me he wanted to pass it on to people he knew. I was very cynical about it, I didn’t think he knew anyone. He ended up passing it on to someone, that passed it on to someone else, that gave it to Trent Reznor. At the time—this was right after 9/11—there was resistance to booking us. Trent Reznor was in a stage where he was really into the political side of things and he didn’t care that we were Pakistani. He heard our demo and was really into it. It wasn’t until we were on tour that I think we realized he picked us over a lot of other acts. Trent Reznor was an amazing support. He met every expectation I’ve ever had; no one else has really done that. That was a big push for me. We didn’t have an album out. We had never been on tour before. We went from playing in front of 15 people in Philadelphia to playing in front of 30,000 people in venues all over Europe. I thought, either this is the beginning of something amazing or the peak of my whole life. Either way I thought it was cool. It was rock-‘n-roll fantasy shit.

BENNS: How did you get connected to Mad Decent? As someone who creates rock music, you’re a unique choice for a label that is primarily DJs.

MALIK: I met Diplo at a show in Athens. He was really funny, setting firecrackers off on stage. We came back to Philly together just to hang out—we played a lot of basketball. It was a friendly thing. One day I played him a couple of songs and he asked if we wanted to do a 7″ record. His manager overheard us and he said “Hey, if you guys are going to do a 7″, let’s just put together a deal.” I sat on it for a little while, talked to a few other labels. But, Mad Decent just seemed right. Diplo is… whatever you have to say about him, on the ground level he is a genuine article.

BENNS: POPO started as a band with your brothers, but at this point you are the only member; what happened?

MALIK: When we started back up again on Mad Decent, I could tell my little brother Shoaib was just dragging his feet. He wasn’t happy. We’re very close, but that was the first time we had hung out together that much in our lives. We don’t share the same circle of friends. He left, and me and Trav decided to just go for it. But as the process went on it just didn’t seem right. His heart also wasn’t in it, he wasn’t into the lifestyle.

A lot of people think we had this bad breakup, but it wasn’t like that at all. When you’re with your brothers, you don’t want to work like that, you just want to hang out—be with them. When my budget’s big enough, and the tour is right and I deserve to have them there, my brothers will be there. But in the meantime, I don’t want to make it a shtick.

BENNS: You’ve toured with a lot of different acts, did any of those experiences really resonate with you?

MALIK: I think the most inspiring was touring with Derek Miller from Sleigh Bells. I think the thing about Derek that I connected with, and what I connect to with a lot of artists I work with, is that we grew up on Michael Jordan. We grew up wanting to be the greatest of all time. Derek has that mentality. It was the first time I had a friend that I could relate to weird things with—but he was actually killing it. I was addicted to heroin up until that tour, and I detoxed on that tour. Derek had just lost his father and his mom was diagnosed with cancer, and just hanging out with him and seeing him work through these tough situations really changed a lot for me.

BENNS: Your first album, Dope Boy Magick, has been a couple years in the making—what was that process?

MALIK: Initially we went through a lot of producers working on this. We worked with Phil McKellar, who worked with Silverchair. We worked a little bit with Ariel Reichstadt—he’s in the news now because he worked on that new Usher song, “Climax.” It was really cool to work with them, but they were really busy and it ended up tripping up the band a little. So then I said “Yo, find someone that has time—that’s willing to work exclusively on this,” and we got put in touch with Nick Launay. He said he thought we had this Ramones-in-Bollywood vibe, which I loved, and we started working with him. He knew this guy named L. Shanker, that built a double violin—he plays with Peter Gabriel, Phil Collins, huge bands. But for some reason, the whole time we were in the studio, Shanker kept telling us he worked with Jonathan David of Korn, that was the only name he dropped, it was awesome! Maybe he thought we would be really into that. I thought that was so cool. That whole experience in the studio with him really cemented that this was what I wanted to do. That’s basically how the sounds came together, mostly I just wrote it on my own—then worked together with some producers. I sat down with Diplo, and he helped me pick and sequence the songs.

BENNS: The album’s sound is extremely varied and there are a lot of not so subtle influences of cumbia, Middle Eastern music, electronic, dub, and grunge. What do you want listeners to take away from it as far as what POPO’s specific sound actually is?

MALIK: That was also part of the reason for getting rid of this whole facade of the band. The album doesn’t make sense when you think of it as a band. When you think of it as a producer that made some music, it makes total sense to me. I didn’t want to come into this project making one specific kind of music. That’s why it’s called Dope Boy Magick. I’m proud of this as a producer in general. That was a challenge for me, making all of this music that sounds different, but still feeling like it goes together. I’m not sure if everybody will agree with that, but… [laughs]

PO PO’S DEBUT ALBUM, DOPE BOY MAGICK, IS OUT TODAY. FOR MORE ON THE PROJECT, VISIT ITS FACEBOOK PAGE.