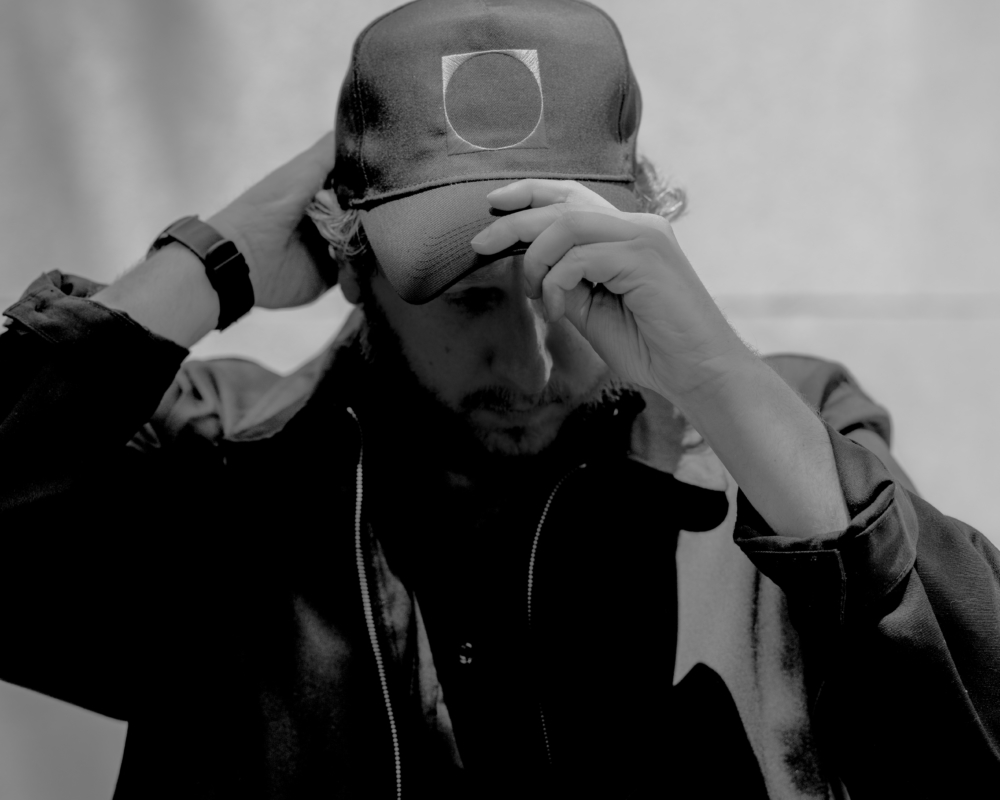

Oneohtrix Point Never Thinks the Internet Sucks, But What Else is There to Be Addicted To?

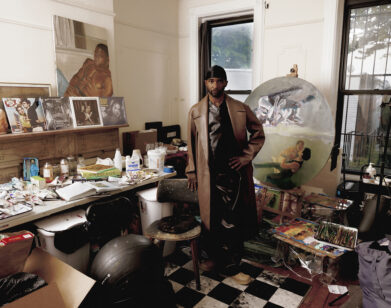

The noises you hear when listening to Daniel Lopatin’s productions made as Oneohotrix Point Never are the swan song frequencies of a dying internet. And the scope of his project is growing. This summer, he staged a “quasi-libretto” called MYRIAD at the Park Avenue Armory, performing songs off his 2018 album, Age Of. This “concertscape,” as an oversized playbill described it, included performances with cellist Kelsey Lu, noise musician Prurient, visuals by Nate Boyce, inflatable landscapes, and a band of dancers clad in cowboy contagion uniforms. It was a vision of something run amok—with Lopatin serving as a reserved master of ceremonies, controlling his set pieces from behind a midi keyboard. This spring, Lopatin plans to bring an expanded MYRIAD to London’s iconic Round House.

Up close, Lopatin is less reserved about the scarred informational landscape we find ourselves in. The optimism found in the dark spaces of Web 1.0 rabbit holes and VHS fantasies is a key input that Oneohotrix Point Never has collected and redeployed. Whether through working for directors Sofia Coppola or the Safdie Brothers, or producing rejected demos for Usher, or through his latest release Love in the Time of Lexapro, out this month, Lopatin is filtering the grotesqueries of visual culture into something more tactile. He spoke with Interview about this very specific practice, the end of the internet as we knew it, his bastard genre-invention Vaporwave, and his tendencies to produce kitsch content. “You are what you eat,” he said. “Kind of.”

———

NATHAN TAYLOR PEMBERTON: You’re really good at the internet.

DANIEL LOPATIN: My friends tell me I’m the best of the crew at the internet. I’m the internet boy.

PEMBERTON: The internet is boring now.

LOPATIN: Yeah, it sucks. It’s become boring, to me. I think Web 2.0 was the beginning of the homogenization of the internet where everything had been templated. It’s content management driven and just a giant pasteurization complex. Everything looks the same. All websites look the same. Blah, blah, blah.

PEMBERTON: How much are you on the internet every day when you’re not producing?

LOPATIN: Really good question. I’m almost just a basic addict like everyone else. Instagram, Twitter. Refresh, refresh. All these things that were not a factor 5, 10 years ago. I don’t really like it.

PEMBERTON: These are the new home pages now. I miss finding the deep—

LOPATIN: Raw emotion.

PEMBERTON: Yes, the weird blogs. Broken Angelfire sites. Shoddy HTML stuff.

LOPATIN: The blogs were great. The blogs I really miss. Just look at the history of the internet. It’s oriented around hyperlinks, text. Even video games. The first adventure games basically dealt with poetry. As we moved away from that, towards the individual-oriented way of navigating the internet, we lost the ability to dream that way—in stories and ideas. The depth of language, I think, is missing. There is a connection between this and the idiocy that we’re all feeling so constantly. It’s sad to me that the main stage of history is a story of how we became this visually obsessed, extremely narcissistic, extremely concerned about image, culture. At least in the West.

PEMBERTON: You’ve done a very good job of articulating this cultural evolution (or regression) with OPN. Would you say that some portion of its success is because you’ve attached your music to such extreme visuals?

LOPATIN: We have this thing amongst the extended OPN family, that movement we’re trying to orient ourselves around called “Compressionism” — basically a way of harnessing an overflow of images that are there to either titillate you or to make you feel bad about yourself, whatever they’re there to do. It’s a way to conquer all of these inputs. It’s about organizing and sort of re-appropriating things that you don’t want necessarily and seeing them in a way that is personal.

PEMBERTON: You’re distorting things, everything, wherever you can.

LOPATIN: It’s the Jewish mother in me. Trust me. That thing when you grow up in a family with a mother who is really trying to make sure everyone’s not just fed but really well fed. Oh come on, do you want more? Let me give you some more. And then my hero, Stanley Kubrick, taught me that every frame you decide to share with people should be super specific and filled to the brim with choices. Specificity actually lends itself to being a Maximalist. I think of it as extremely helpful to just consider all the sub-dermal shit that doesn’t usually surface. It may seem like a portentous amount of information, but actually what I am trying to do is just be generous.

“We lost the ability to dream that way—in stories and ideas. The depth of language [on the internet], I think, is missing. There is a connection between this and the idiocy that we’re all feeling so constantly.”

PEMBERTON: Do you have any complaints to lodge about the state of the conversation online?

LOPATIN: Vehement zealotry on both sides, like intense anti-intellectualism, bothers me a lot.

PEMBERTON: A major mood, for sure.

LOPATIN: Immediately, I feel alienated because I like words. I like explication of ideas, even if I’m wrong or even if it’s a struggle or if it’s a work in progress. Another thing I don’t like: denial of works in progress because everything is being super assessed so quickly.

PEMBERTON: If I assessed your works as kitsch, how would you respond?

LOPATIN: Kitsch has been in my vernacular.

PEMBERTON: Super kitsch.

LOPATIN: It is super kitsch! I took a class when I was 19 or 20 years old at Hampshire College with an extremely talented and incredible thinker, philosopher, professor named Monique Roelofs. She taught a class on kitsch, and I made a piece of music for it. This is before 9/11. The first lyric of this song was: “The plane, the plane flew through my window.” It detailed the moments before this plane comes through this apartment where this, like, archetypal rock star is writing a song with one knee up, smoking a cigarette. I just like cliches. I like tvtropes.com. It’s pretty much my bible.

PEMBERTON: I’ve actually never seen.

LOPATIN: Check that out. It’s one of the last great websites. If not a living testament to our culture. Kitsch is very important to me.

PEMBERTON: I found an old jewel case for the Chuck Person’s Eccojams cassette in my apartment not long ago. It’s a cult item now, I hear.

LOPATIN: The guy who pressed [Eccojams] has been amazing about not cheaply profiting off of it. We’ve never done a second run.

PEMBERTON: I look at the Discogs page now and then. One was recently listed for $2,000!

LOPATIN: There’s like a really, really grotesque sub-market. That’s what you get when you launch a genre [Vaporwave], I suppose.

PEMBERTON: People are selling cheap imitation bootlegs of it, it seems.

LOPATIN: That’s so whack. That’s fucked.

PEMBERTON: Are you going to re-issue it?

LOPATIN: I don’t see the point. It’s a mixtape, where we slowed down other people’s music. So, making money off of that … I mean. It would be cool to do a re-release as some sort of charity scenario. Just do another 60 tapes, exactly like we did the first time, and try to raise money for Autism research. I think about that a lot, I think about the scenario where you’re not able to connect to your environment on the level that others are.

PEMBERTON: Are you aware of how your work is perceived on the internet?

LOPATIN: From lurking on forums, I can ascertain certain tendencies.

PEMBERTON: Do you consider forums a kind of raw barometer of the cultural psyche?

LOPATIN: It’s place of scatology and truth. You have to look in forums if you want to actually deal with reality a little bit. But at the same time, the difference between Rabelais’ marketplace, for instance, and our internet forums is that you couldn’t fucking hide behind an anonymous handle. You were responsible for your niche. You were responsible for your bag of bones.