GUT CHECK

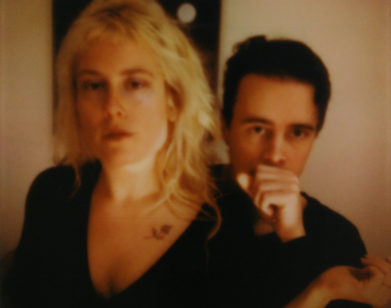

“I’m Looking to Heighten the Stakes”: Kinlaw and Jae Matthews on Queer Sex and Southern Pride

Carolina-born artist Kinlaw is something of an adrenaline junkie. “I’m looking to heighten stakes, especially physically, and have something to push back on,” she told Jae Matthews, one-half of electronic duo Boy Harsher, of her artistic ethos. Since her spontaneous move to New York at 17, Kinlaw’s practice of music, movement, and choreography has been propelled by full-throttle impulse, from her past works at MoMA PS1 and Pioneer Works to later collaborations with SOPHIE and Caroline Polachek. On her latest album, gut ccheck, released just last week, she followed that intuition by taking her demos to the dance studio, resulting in 14 tracks Matthews described as “industrial nu metal, hyperpop, and a conceptual sound piece.” When they got together to talk about beekeeping, the Silent Barn era, and composing music with the body, they both agreed: “Music gives you something so totally insane. It hits so good. It’s like a drug.”

———

JAE MATTHEWS: Ignore my room or whatever. It reminds me of the episode of The Simpsons where you go to Mo’s house and he’s like, “Don’t tell anyone how I live.”

KINLAW: No, it looks cool. Are you in a hotel? You’re in residency right now, or you were?

MATTHEWS: I was, but no longer. Now I’m just at the Jupiter Motel in Portland because I’m flying out tomorrow morning. I was staying in Seaview, Washington. Are you reporting live from Brooklyn?

KINLAW: Yeah, I’m in Brooklyn, but I’m upstate about half the time.

MATTHEWS: You grew up in North Carolina. Do you think the landscape is similar to upstate? Do you think that’s why you’re drawn to it?

KINLAW: A lot of it is circumstance, but I always wanted to be able to leave the city. My life in North Carolina was like, my dad would take me out fishing and hunting, and now we have bees—

MATTHEWS: On the property.

KINLAW: Yeah. They survive the winter. But I got stung on the temple, so I kind of hang back. But it’s that hybrid of quiet, deep thinking mixed with putting things to action. It just works for me. And my capacity for hanging out is so much higher.

MATTHEWS: Right, because the over-stimulation of the city makes people a little more aggressive.

KINLAW: It does. And now the weather’s turning and what we all thought was pretty serious mental malfunction is actually just a reasonable response to the environment. Hopefully, we’re all going to find our footing again.

MATTHEWS: My first exposure to your work was over 10 years ago with your previous project, SOFTSPOT, and I was really drawn to it because it felt very Southern gothic. And at the time, that was what I was interested in, living in Savannah. A real ragged edge, but delivered in this angelic tone. I’m such a sucker for artifacting, and I want to know: when you were a child, was this what you wanted to do? Were you singing when you were wandering around the house?

KINLAW: I think where I grew up in North Carolina, there weren’t really any examples, but I had this very sincere way of getting involved with things. Even things that didn’t make a whole lot of sense. I was in three church choirs. I never went to church, but I was in all the choirs. I definitely sang all the time. I was a big fan of the repeat; to rehearse a song and then repeat it and repeat it and repeat it. I still am, but focus looked a little different back then. I think maybe my focus changed when I got that Tamagotchi.

MATTHEWS: The first screen, right?

KINLAW: Yeah. But I moved to New York when I was 17 and I didn’t have a plan or go to school. I had gone to Times Square once with one of my choirs and we saw the Rockettes perform, and I was like, that place. I didn’t know a single thing about it, really. It was years and years of being here and not really knowing why I was here. It took me a long time to find anything meaningful in my artistic output.

MATTHEWS: You were discovering what kind of vocalist you were trying to be. Was SOFTSPOT being created at that time?

KINLAW: Yeah. I was maybe 20 or 21 and I got in an argument with a roommate and I was so, so angry at her, and I was like, “I’m going to write a song about her.”

MATTHEWS: Oh my gosh.

KINLAW: I was just so mad. I had stayed in touch with Molly Gottschalk, who had left my hometown and gone to Savannah, and she had all these really cool friends. My first wave of cool artistic friendships were all Savannah people, and she had introduced me to this great friend and recording artist Colin Alexander, who also helped out on the album. I emailed him for maybe a year-and-a-half before we finally got together. I asked Bryan [Keller Jr.], who is the other co-founder of the band, to come with me, and Bryan is really very naturally talented and kind of has it all. So we kept playing and writing and that was the basis for starting a band. I did that band for a long time, maybe a decade.

MATTHEWS: And what an era, too. Correct me if I’m wrong, but that was the New York Silent Barn era, right?

KINLAW: Yeah.

MATTHEWS: A very optimistic time in music, a very special time.

KINLAW: It was a great time to be young, to be open to the kinds of touring that we did and y’all did. It was a sincere time in artmaking and in music.

MATTHEWS: And maybe there was more of a blend of genre. People were less afraid of mixed bills. I think we were on a bill with you and Dougie and PC Worship, just kind of a psychotic combination, but people were interested in seeing that all at once. I get the sense that there isn’t the same level of underground nowadays.

KINLAW: I say that and every time I say that, I’m proven wrong. There’s really, really exciting things happening in underground club music, as well as performance. Those kinds of spaces are still around, and when they do close, something else seems to pop up. But I think I lost touch with the DIY music and bands scene.

MATTHEWS: Maybe that is part of the shifting paradigm. Maybe rock and roll isn’t over, but it is more about the body and a different way to create sound. I think this is a great segue into your album.

KINLAW: You’re literally so good at this, and you look so chic with your lipstick on.

MATTHEWS: Oh, come on. Okay, I want to talk about the name. I had this insane conversation with a friend of mine a couple years ago about intuition training, and the major lesson was learning how to listen to your gut versus your head. The premise is your head yells and your gut whispers, and women are conditioned to not hear the whisper. You are trained to push the whisper away, and part of this training is to quiet the yelling in your head. This record feels like an exploration of trying to find the voice within your body. It’s very erotic, but also so anxious. Also, I didn’t realize that you were a student of neuropsychology. I want to know about the process.

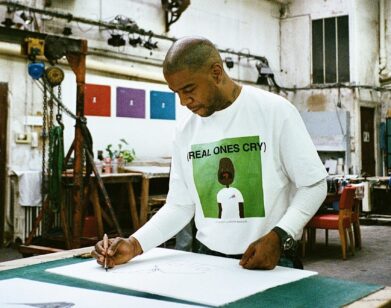

KINLAW: I think I try to find different entry points to make lyrics and performance happen that coincide with this music. And the throughline is that, especially in terms of the anechoic chamber and sitting in intense silence for so long in preparation for this kind of work, I’m thinking about how our minds and ears interfere with sound. The process for this record had a lot of different phases. A phase of solitude, a phase of writing upstate, a phase of writing the sounds, and then writing and production with Carlos Hernandez, Jonathan Schenke, Tony Seltzer and Jake Aron, who I did all the vocal production with.

MATTHEWS: Cool.

KINLAW: I’m late with words, almost always. But what’s never late is an impulse, and I wanted this to have a lot of adrenaline. I wanted it to move quickly, so I took all of these demos into a dance studio. That’s really where I feel like I start to come into myself. In this case, I took it to Otion Front, which is a little square of important history in my life. That’s where I started to think about intention and movement vocabulary. Months later, I brought in this amazing choreographer, Marla Phelan, who really helped me make sense of the mess, so a lot of the lyrics come from this isolated time in the dance studio.

MATTHEWS: So when you’re building out the tracks with these producers, you develop the melodies sonically with just vocalization, but no words?

KINLAW: Usually. I just have to let the feelings go and know nobody’s really judging me.

MATTHEWS: It’s fascinating because to me it sounds incredibly physical, and that makes sense because you’re also a choreographer. You collaborated with Kathleen [Dycaico] on “SPIT,” which is an important visual piece for the album. You’re confronting the fourth wall. I saw some of the BTS and it seemed like you had to be incredibly careful.

KINLAW: There’s so many fun things to talk about, but the first thing that I’ll say is that before this call, I rewatched so many of your music videos and saw so many familiar faces. I saw Sigrid Lauren, Aaron Ricks, Tara-Jo Tashna, and of course Kathleen Dycaico and Jill Ferraro. Kathleen is beyond bestie. She’s really been a massive support system and she never runs out of energy and ideas. I was looking at the years that some of these videos were made, and y’all really captured such an important moment in the community and I’m so glad you did, because a lot of the work that I did with these people was performance-based and was never captured on video. I didn’t know anything about documentation, and even if I did, we just didn’t have that kind of resource.

MATTHEWS: I think among many things, you’re referencing Unboxing The Compass, which was your piece at MoMA PS1, and that was certainly a place where we poached many of your performers because we went and were like, “Oh my god, who are these people?” Kathleen was somehow levitating above a mattress like the most strong, holy person I’ve ever seen in my life. I’m very thankful that we met you in Savannah, because then we were able to meet all these people and ask if they could be in our videos.

KINLAW: It’s so cool, and I hope it continues as y’all continue to build your visual world. That show wasn’t an album necessarily, but I kind of treated it the same way.

MATTHEWS: I remember the sound being its own character, a huge part of that.

KINLAW: It was. There were all these different elements and textures that were also used as set design and props, and it was meant to forefront the way that dance changes how things sound. Really having to consider movements as part of a score as opposed to just moving through space.

MATTHEWS: And “SPIT” is very much a performance piece.

KINLAW: Yeah, this process was kind of dangerous, let’s say. As the work continues, I’m looking to heighten the stakes, especially physically, and have something to push back on. My original dream was to perform it high up and everyone is looking at me, getting the full 360. I created choreography for this song based on that vision, so it’s really active. And Maddy [Talias], my talented DP, suggested this motion control situation that reminds me of some cobra snake that’s flying at you fast. But my job was just to get my endurance up, to take the protein and work hard. That video was just a total labor of love. I feel like that’s the cool thing about my life so far as an artist, that we find ourselves with big ideas and no budget, so it takes people really rallying around the idea, and that is what happened here.

MATTHEWS: What is the story? I hope this isn’t annoying, but is it a confrontation of AI or of your sexuality?

KINLAW: Originally it started off as a me versus me thing, and some of it is a little bit of an ode to queer sex.

MATTHEWS: “Things switch.”

KINLAW: Literally. I’m not that interested in AI. I don’t fight with it, or I just don’t think about it. I think everything’s going to work out with AI. I could be very, very, very wrong.

MATTHEWS: I know. I’m just like, I don’t know if I even have enough emotional space to manage what disastrous outside impacts are coming.

KINLAW: I think that’s where I’m coming from too. I’m actually not releasing a vinyl for the work. I’m releasing a book. You probably don’t know that because I’ve only said it once, and I probably should say it again.

MATTHEWS: Oh, I didn’t know.

KINLAW: It’s because I really want to highlight the process behind things. There’s just absolutely no way I could scrapbook it all into one book, but I really tried. And as a working artist in today’s time, there’s so many things that I can’t do, but what I can do is highlight effort.

MATTHEWS: That’s really special. I hope it’ll be at a bookstore.

KINLAW: Me too.

MATTHEWS: Bayonet Records, put it at my local bookshop. I wanted to ask, the opening track, “What You Own Owns You,” is a sample. Is that Harry Cruz? Is it from Independence Day? What is it?

KINLAW: It’s my dad. His name is Lyman, otherwise known as Lyman The Legend. It’s just from a conversation. “What you own owns you” is a saying that I grew up with. He has so many Southern sayings, and I do realize that his accent is so deep that a majority of people won’t be able to understand it. They might just hear it as some kind of mumbling that they can barely parse out. He opens the record. He also opens the performance every time I do it, and now it’s anchoring down my experience after the album has been recorded. Sometimes I have this wish that I had more, or had family money or this or that, but my dad and my family have this real sense of Southern pride by not having a lot, and the perspective that we’re so lucky to not be so tethered to so much. I’m really glad that you asked about it. You’re actually the first person to ask.

MATTHEWS: You should thank the bug in my SoundCloud because it just was repeating over and over again as I was driving. And then “Ride The Ride” reminds me of “Pony” By Ginuwine, which is maybe the first song I heard when I was a youth that I remember being like, “I think this song is about something I’m not supposed to hear.” But to me, “Ride The Ride,” is about maybe being playing into a system that’s just using you and exploiting you.

KINLAW: It’s a theme that a lot of people can probably relate to, but in this particular case, I think quite a bit of spite came into the track. I let myself air out some anger about a situation, so I gave it the title, “Ride The Ride,” because that’s what I did. Had I not done that, we wouldn’t have this issue. A lot of it is spent on the ground, crawling, trying to find these words. It’s whispered, but sometimes by being quiet, people lean in to listen a little more as opposed to yelling your head off.

MATTHEWS: It can be so much more powerful, especially in music that is already playing with aggression. Have you heard the Whisper song?

KINLAW: Yeah. This track was also very technically challenging and we were like, “Well, how did the Whisper song do it?”

MATTHEWS: It’s wild. Is there anything else you want to talk about?

KINLAW: I want to ask you how you keep going even when you maybe don’t want to at that moment, knowing that maybe next week or maybe even the next day, you’ll want to keep going again. How do you keep your endurance?

MATTHEWS: It’s a question I ask myself all the time. Years ago, I was cleaning Airbnbs and working the door at a bar and someone I know made this joke like, “The first time I stepped on stage, I knew what was going to ruin the rest of my life.” He was a comedian or something. I’ve never forgotten that. Whenever I’m having a really fucking hard time, that’s what I think about. Two years ago when mom died, I was like, “What am I doing?” The band has always been prioritized over everything else, and if I were to do it over again, I would renegotiate my priorities. But music gives you something so totally insane. It hits so good. It’s like a drug. I think we do this because we’ve figured out a way to translate something totally indescribable inside of us to others, and that’s very special.

KINLAW: I completely hear you. And when I think of Boy Harsher’s work, I think of live performance. I don’t think of the screen. I feel the same way about myself. My keep going wheel is just being in the room with folks, and there’s no way that that can be taken away.

MATTHEWS: I mean, think of the bees.

KINLAW: The bees need the other bees. That’s how they made it through the winter.

———