Good Enough for Me and Benjy Ferree

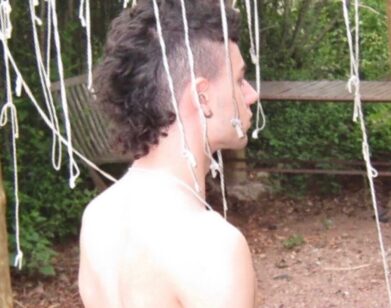

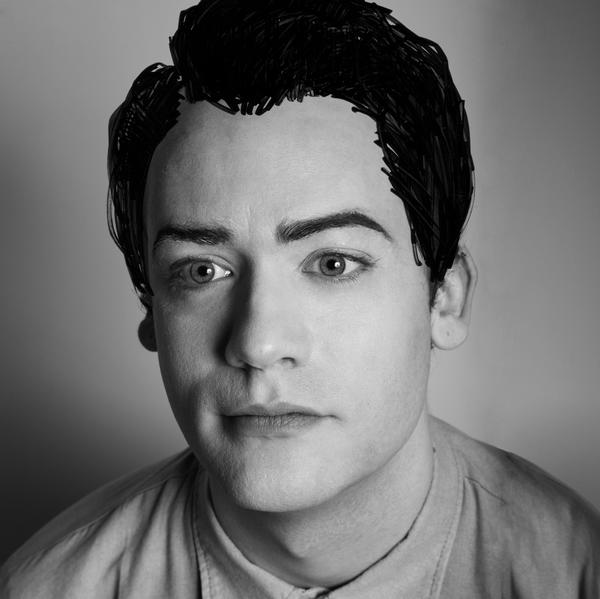

Washington, D.C.-based singer-songwriter Benjy Ferree is quick to correct those who would call his new release, Come Back to the Five and Dime Bobby Dee Bobby Dee, a concept album. He clarifies that it is, rather, a tribute record-written in honor of Bobby Driscoll, the child actor who played the title character in Disney’s Peter Pan. (Ferree is fully devoted; he even appears in character as Driscoll on the album’s cover.) When Driscoll hit puberty and suffered a severe case of acne, Disney dropped him, leading to years of decline, drug addiction, and Driscoll’s eventual death in an East Village tenement at the age of 31.

Given its source material, the tone of Bobby Dee is surprisingly hopeful—the album is a mishmash of all that’s been good about American pop for the last sixty years. Its standout track, “Fear,” may well be the first great song of 2009. Come Back to the Five and Dime Bobby Dee Bobby Dee comes out February 3, and Ferree will begin touring a few weeks later with his fiancée and his best friend in tow.

Alexandria Symonds: When did you first hear the story of Bobby Driscoll?

Benjy Ferree: Well, I’ve always known who he was, from Treasure Island and Song of the South. He got an Oscar for that movie The Window. Then, of course, he did the voice of Peter Pan. Just like Andy Serkis, who played Gollum in Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings—that actor, Andy Serkis, would wear a green-screen outfit and act out all the parts, and they animated him over the footage. That’s the same thing Bobby Driscoll did in Peter Pan. He dressed up as Peter Pan, and he ran around the room reciting the lines. So the Peter Pan that’s in the Walt Disney animation, that is Bobby Driscoll. That’s what he looked like; they just put red hair on him and kind of Disney-fied him.

AS: I didn’t know that.

BF: Yeah… You can’t really avoid him. He’s part of American cinematic history. So I’ve always known who he was, but I didn’t know that he died at the age of 31 until a year ago, if that. When I found out about how he died, I wrote this record pretty fast. And I’ve never really done that before. I also didn’t know that he was buried on Hart Island in a pauper’s grave. I didn’t know that a year after he died, his mother tried to get a hold of him because his father was just about to die, and she had to get the FBI and Walt Disney studios to help her out, to try to find her dead son—and she didn’t even know he was dead. In him I felt like it was my childhood that was squashed. I felt like it was a part of myself that I didn’t even know about.

AS: In the story of Bobby Driscoll, do you think of Disney as being responsible for his downfall—or is it not that black-and-white?

BF: No, I don’t know anything about that stuff. There’s not much information. It’s a tribute record coming from my perspective, because I didn’t know his perspective. I didn’t know anything about him. I just felt like the 20th century swept him under the rug; I didn’t feel like Disney did. That’s between Disney and Bobby Driscoll. I have no idea.

AS: A lot of the songs are written in the first person, though. Did you feel like you were inhabiting Driscoll? Was that what you were going for?

BF: I definitely felt like I was moved by something or someone to write, and I had to be open to it. I will say, though, that I still do in a lot of ways feel like I inherited his soul. I chose to embrace it, at the very least. … Yeah, I was moved by the story of Bobby Driscoll. What’s the story of Bobby Driscoll? I don’t know, but my story of Bobby Driscoll is Come Back to the Five and Dime Bobby Dee Bobby Dee. But also, the record has a second name. Did you know that?

AS: No.

BF: The other name is Pax Americana.

AS: I was actually going to ask you about that, about the various musical styles that you employ on the album-whether you think of that as a collection of the different things that Americana can mean.

BF: I grew up singing gospel when I was a kid, so a lot of gospel came out. “The Grips” is about Bobby Driscoll going to heaven, and the song “Zipperface Blues” is a song that he always wanted to sing to his wife and kids, but he couldn’t. You’re writing thinking about another human being, but a lot of yourself comes out, too. I didn’t really plan all this out; I just had a feeling and went for it. Also, I moved to California when I was young and naïve, and the fact that I got out alive is pretty amazing. Bobby Driscoll didn’t. I don’t know what that means, but you realize you’re grateful to be alive.

AS: Obviously, the story of Bobby Driscoll is a sad one, but a lot of the songs on your tribute album are more upbeat than they are explicitly mournful.

BF: Oh, yeah. I think the record’s a beautiful record-meaning happy. I think it’s a peaceful ending—I don’t think it’s as gothic as it came across in the newspaper a year after they found his body. We don’t know what he was going through in the last few years of his life. But I imagine it would be pretty beautiful, because that’s the kind of spirit I felt.