Exclusive Video Premiere and Interview: ‘Lonely Sinner,’ Teddy Blanks

Teddy Blanks is a man of many talents. At his day job working at CHIPS, the design studio he co-founded, Blanks creates top-notch creative projects for a wide variety of clients. (Perusing his website reveals work ranging from the official Thomas Pynchon e-book collection, to film credit sequences, to a lyric book for Eleanor Friedberger’s new album.) In his spare time, however, Blanks moonlights as a troubadour of wryly sentimental pop music.

Blanks’ new album Therapy, released earlier this year, is by turns hilarious, heartfelt, and seriously catchy—often at the same time. Song topic ranges from relationship travails to tongue-in-cheek explorations of celebrity. The album’s first single, “Famous Friends,” for example, laments that a celebrity lover has become successful, while no one seems to pay the slightest attention to the songs the narrator puts up on the Internet.

“Lonely Sinner,” too, is inspired by one of Blanks’ successful peers. “There was a movie called The Exhibitionists that a friend of mine directed. It’s sort of based on a character in the film that’s a transsexual pop star,” says Blanks. He then pauses before before revealing his other, more close-to-home source material. “I was also thinking about a breakup I had gone through recently,” he says. “It’s about forgiveness. And a little bit about anger.”

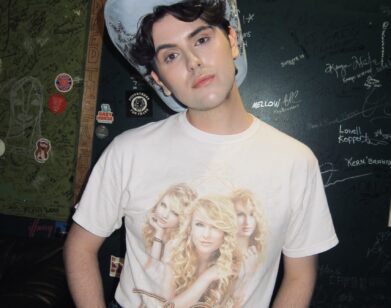

Interview caught up with Blanks to talk about the M. Blash-directed video for the track, applying drag makeup with the help of his friend Emily Weiss, and his intensely personal new record.

NATHAN REESE: Who came up with the concept for you to wear the makeup?

TEDDY BLANKS: I always thought of the song as me talking to myself a little bit. The director, M. Blash, came up with the concept the day before we shot it. We were just going to shoot it as a straight-ahead performance video in my apartment, and then I e-mailed him being like, “Should we extend the concept a little bit—maybe make it more exciting? Should we get a girl that maybe I could sing it to?” And he was like, “Actually, I was going to ask if you’d dress up as a girl and do the song, but I was afraid to ask.” I was like, “That sounds great!” I called my friend Emily Weiss, who runs a beauty blog called Into the Gloss and was like, “Do you want to come over and do my makeup for the shoot?” We ran through it a couple of times where I just did it normally, and then she did the makeup, which took a couple of hours—she bleached my eyebrows.

REESE: You have a pretty cool day job. Has work as a designer opened any doors for you as a musician?

BLANKS: A passion of mine is doing the title sequences for movies. I’ve done 25 or so of those in the last couple of years; It’s really fun and gratifying. I also get to work with cool directors for my video projects because I’ve worked with them on their movies and other personal projects. M. Blash had a movie at South by Southwest called The Wait that I did titles for. We had known each other before that, but he did the video as a little exchange.

REESE: Do you see similarities between your work as a designer and your work as a musician?

BLANKS: I think they are related. A lot of design is about moving things around and lining things up, and the way I make music is electronically—I use [the computer program] Logic. Somehow the synthesizers lining up on a grid relates very much to the design work that I’m doing: the process feels similar. And it comes from the same sort of spirit, I think, too.

REESE: Do you worry about having to split your time between life as a musician and as a graphic artist?

BLANKS: I used to think that I would have to make a choice, but what’s playing out is that I’m probably not going to have a career as a huge pop star, but I can release music and have an audience for it that can enjoy it. And I can put videos on the internet, have people watch it and dig in, and feel I’m like participating in that way, but not make it my full-time thing. I can still do the design work—which I love to do—and have that be my career, and then also put out music whenever I feel like it. Which is a really great thing to know that I can do. Even if the balance shifted the other way, I would always find a way to balance the two of them.

REESE: Your lyrics play a large part in your songs. Who are some of the lyricists you look up to or have been inspired by?

BLANKS: I love David Byrne, just for the abstract strangeness of it. I love Jonathan Richman, that’s on the opposite end—there’s still a kind of kookiness, but he’s very vulnerable and direct all of the time. [I like] Elvis Costello. I guess I like lyrics with a lot of wit and a little complexity. I love Stephen Sondheim.

REESE: For your own lyrics, do you tend to write abstractly, or about literal experiences from you own life?

BLANKS: Up until this record I had always written songs from a fictional point of view—always abstract ideas, not necessarily things that were happening to me. Then I kind of decided deliberately for this one, I’m going to actually write songs about myself and what I’m going through—the losses and abandonment in my own life. It was a concept album about being personal, only it was the first time I had ever done it. Most songwriters start out by writing about shit that happens to them in their own lives, but for me, I had to take it as a conceptual project first. The songs on this album are all very personal and, sometimes, very literal.

REESE: Considering the subject matter, do you find it difficult to expose yourself to strangers listening to the record?

BLANKS: Yeah, I guess I was a little afraid of that. I had the album done for a while before I actually decided to release it. What helped with that decision was a song—it was the first track on the album—called “I Was Abandoned.” It was a catchy pop song about every loss I had gone through in my life, starting with the death of my father. I would play it to people and they would kind of cringe and be like “Uh, that’s really out there… that’s really you…” Ultimately I decided I had to take off the one track that was so literal it was almost painful for people to hear it. As soon I was able to remove that one, the rest of them felt just removed enough to be not so specific—not so much baring my soul out there. Because I had one song that was really out there, it feels less crazy to bare my soul on the other songs. Relatively.

THERAPY IS OUT NOW. FOR MORE ON THE ARTIST, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.