In the Doldrums

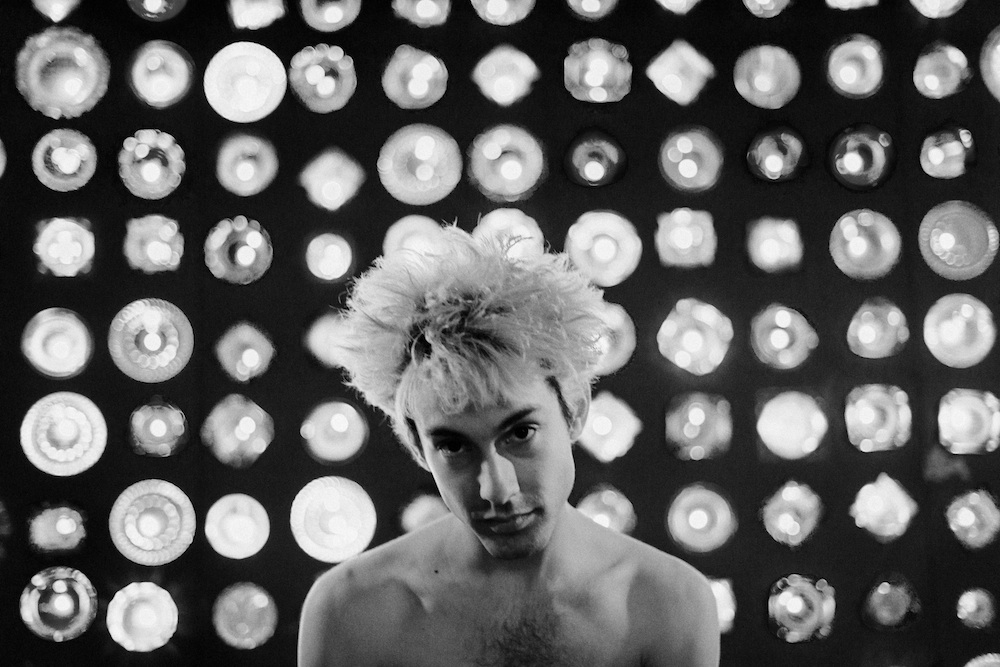

AIRICK WOODHEAD IN NEW YORK, APRIL 2015. PHOTOS BY SHAWN BRACKBILL. GROOMING: NAM VO FOR EXCLUSIVE ARTISTS MANAGEMENT USING JACK BLACK.

“Anxiety is my default state,” says musician Airick Woodhead, better known as Doldrums. Woodhead’s sophomore album, The Air Conditioned Nightmare, released late last month, centers around anguish and distress—a suitable follow up to his 2013 debut, Lesser Evil, which psyched crowds with its layers of electronic sequencing, noisy loops, and mysticism. A self-dubbed “sound collagist,” Woodhead makes music that sounds like the residue of an existential trance, hysterical fit, or lucid dream. It’s delirious, and often uncomfortable, but remains overwhelmingly engaging.

Packed with lyrical examinations of the mundane and an obsession with plasticity, The Air Conditioned Nightmare borrows the title of Henry Miller’s 1945 book, a reflection of the industrial landscape Miller discovered upon returning to the U.S. after 10 years living as an expatriate. Exploring the themes of disillusionment and alienation that Miller expresses in his book, Doldrums’ latest album has us anticipating his next eruption.

Before the musician set off for a tour that will take him through his Canadian homeland, across the U.S., and overseas to Europe, we caught up with Woodhead to discuss the record.

SAVANNAH O’LEARY: So is Doldrums a collective or do you play with the same people all the time?

AIRICK WOODHEAD: Over the years, it might have taken the form of a loose collective, but it is my project, which I started in 2009. I think there have been about 15 different people that have played in the live band or in the recordings. It’s been such a journey with different musicians. It’s not like collaborations where I get a bass player and a guitar player and a drummer and I tell them the parts; it’s more like I find people who really have there own unique artistry and voice and I want them to be themselves within this unit. I tend to only jam with people who I think are better than me, but I remember Björk saying a similar thing once—she said, “It’s no fun if you just get someone who can play the parts you give them.” You want someone who’s going to challenge you.

O’LEARY: It’s been said that you apply punk-rock ethos to electronic music. Can you elaborate on what exactly that entails?

WOODHEAD: The punk scene is a thing you go through in your late teens and early 20s. It’s a kind of community and a place for people who aren’t going to fit into the mold of whatever is going on. I remember in 2009, no one would book Doldrums at a real venue, so it’s not like the DIY community was happening ’cause it was the cool thing to do; it was just that we were all involved in the infrastructure of creating the events and making the venues happen, as well as being the performers.

O’LEARY: You have these different roles as DJ, writer, producer, and performer. What is it like to wear those different hats?

WOODHEAD: I think that’s a real difference between being a musician now and 20 years ago: you have to have a really varied skill set. That’s actually another thing I would attribute to the punk ethos—being able to do all these things yourself. I think Grimes represents that really well by being her own producer, writer, video director, doing everything. It’s inspirational, because if you’ve got a strong vision, you’re the only one that can realize that. No one is going to do it for you.

O’LEARY: I saw a video of you playing “Egypt” in front of a green screen and I was also looking at the images in your digital booklet. You obviously have a very distinct aesthetic. Where does that come from?

WOODHEAD: I’ve been doing collage since I was a kid. My room, when I was growing up, was wall-to-wall with collages of posters that I’d cut up, soup cans that I’d hammered into the walls, and weird action figure fish dangling from the ceiling. [laughs] Then I got into psychedelic music that had elements of collage in it.

O’LEARY: So you still practice visual art often?

WOODHEAD: Everyday, for sure.

O’LEARY: Do you come from an artistic family?

WOODHEAD: Yeah, my mom is a ceramic artist and my dad’s a musician. When I was a teenager, I thought I wanted to be a musician and it was actually the realization that I didn’t just want to be a musician that made me start Doldrums. It was the realization that I wanted to be an artist and express things—not just be a guy in a band. I think that it’s exciting right now to be putting out this album and it’s really big for me to be able to do it, but I’m also not getting too caught up in any whirlwind. I’m more interested in longer term stuff—if nobody knows about me right now, I can keep on working on what I’m working on with people who inspire me. Then, if in 20 years, someone reads about it and loves it, I’m fine with that, as long as it doesn’t detract from my actual work.

O’LEARY: How do you think you’ve evolved as an artist since Lesser Evil?

WOODHEAD: I think I was really frantic. Moving cities was obviously a part of that. I was really swept up by my infatuation with a bunch of bands that are from Montreal—all the bands on the Arbutus label, like Pop Winds, Sean Nicholas Savage, Grimes, TOPS, and everybody. I was the biggest fan of those bands and then I moved here and basically slept on Sebastian’s, who runs the label, couch until he signed me to his label. There was a flame under me to make this happen. Now I’ve got a bit more stability in my life—an apartment, a studio, a bigger label—so there’s a bit more longevity and commitment. I was reading an interview with Animal Collective about how they took 10 albums to get it right. Portishead, My Bloody Valentine, these bands that do it right take the time. That’s where my head is at. Making The Air Conditioned Nightmare was way less sketchy than Lesser Evil. With Lesser Evil, I was sleeping in a band space, borrowing gear, just really trying to make anything work with very little resources. The Air Conditioned Nightmare was a lot better, definitely a step up. Now I feel like I’ve learned so much from that process that the next one I’m just really excited to dig into.

O’LEARY: I’m loving this Henry Miller narrative that you’ve weaved into the theme of your album. Where did the infatuation with him come from?

WOODHEAD: I’ve been talking about stability, but I also have this deep infatuation and fascination with the rock-‘n’-roll road trip experience. When I imagine my paradise, it’s on the Ken Kesey bus, so I wanted to have a little bit of a road trip album. Obviously a lot of the themes or the feelings on it come from a dark place, and they shine some light on it. I also think the whole thing sounds really American—or at least I hope it does. So in thinking, “Okay, what’s an American dark road trip fantastical story?” I was thinking, “Oh, [Henry Miller’s book] The Air-Conditioned Nightmare!” So I just sampled the title.

O’LEARY: I’m also curious about your band name. Where did that come from?

WOODHEAD: That’s also from an amazing traveling story—The Phantom Tollbooth, [which is] better than Alice in Wonderland, I think. This kid Milo, whose life is really dull and boring, goes on this trip through this surrealist world. At one point he gets stuck in the doldrums, where nothing is happening, and there’s these creatures called Lethargarians who just chill out all day. In the film version they look really stoned. At that point in my life, when I named the band, I was 18, paying like $300 rent in Toronto to live in this tiny little hole in Chinatown. I was just thinking, “Oh my god, I want to be this guy in this book, I want to get out of the doldrums and go on this journey.”

O’LEARY: Some of the lyrics in your songs are so great. My favorite is in “Blow Away”—”Honey, lets get rid of the kids / the pets are allergic to them.” Where did that come from?

WOODHEAD: That lyric was on a shirt that I had when I was a kid. It was this pop art shirt, this 1950s happy couple saying, “Honey, lets get rid of the kids, the pets are allergic to them.” [laughs] I’m a real bastard that way. I pick up pieces of stuff all over the place.

O’LEARY: Are you a very nostalgic person?

WOODHEAD: No, maybe I’ll be nostalgic later, but I’m a homesick person. Sometimes that feels like being nostalgic. There’s a lyric in “Closer 2 U” that goes, “How can I be nostalgic for something I never had?” And then my first song as Doldrums is called, “I’m Homesick Sittin’ Up Here in My Satellite.” Both of those songs, it’s like you’re yearning for something, but you don’t really know what it is.

O’LEARY: Does each song have its own story or does each borrow from different stories? What’s the songwriting process like for you?

WOODHEAD: Each song is definitely a different story. People talk about my music kind of conceptually sometimes, but the bottom line is that it’s the way for me to express myself as a person; I feel unable to do that otherwise in my life. So you’ve got a lot of darkness being expressed, but it’s a catharsis for me.

THE AIR CONDITIONED NIGHTMARE IS OUT NOW VIA SUB POP. FOR MORE ON DOLDRUMS, VISIT HIS FACEBOOK.