Antony Spreads His Wings

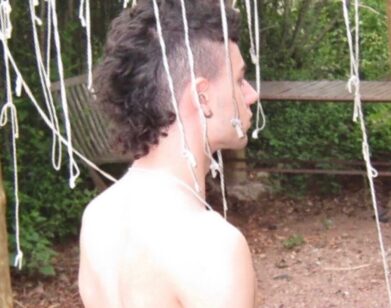

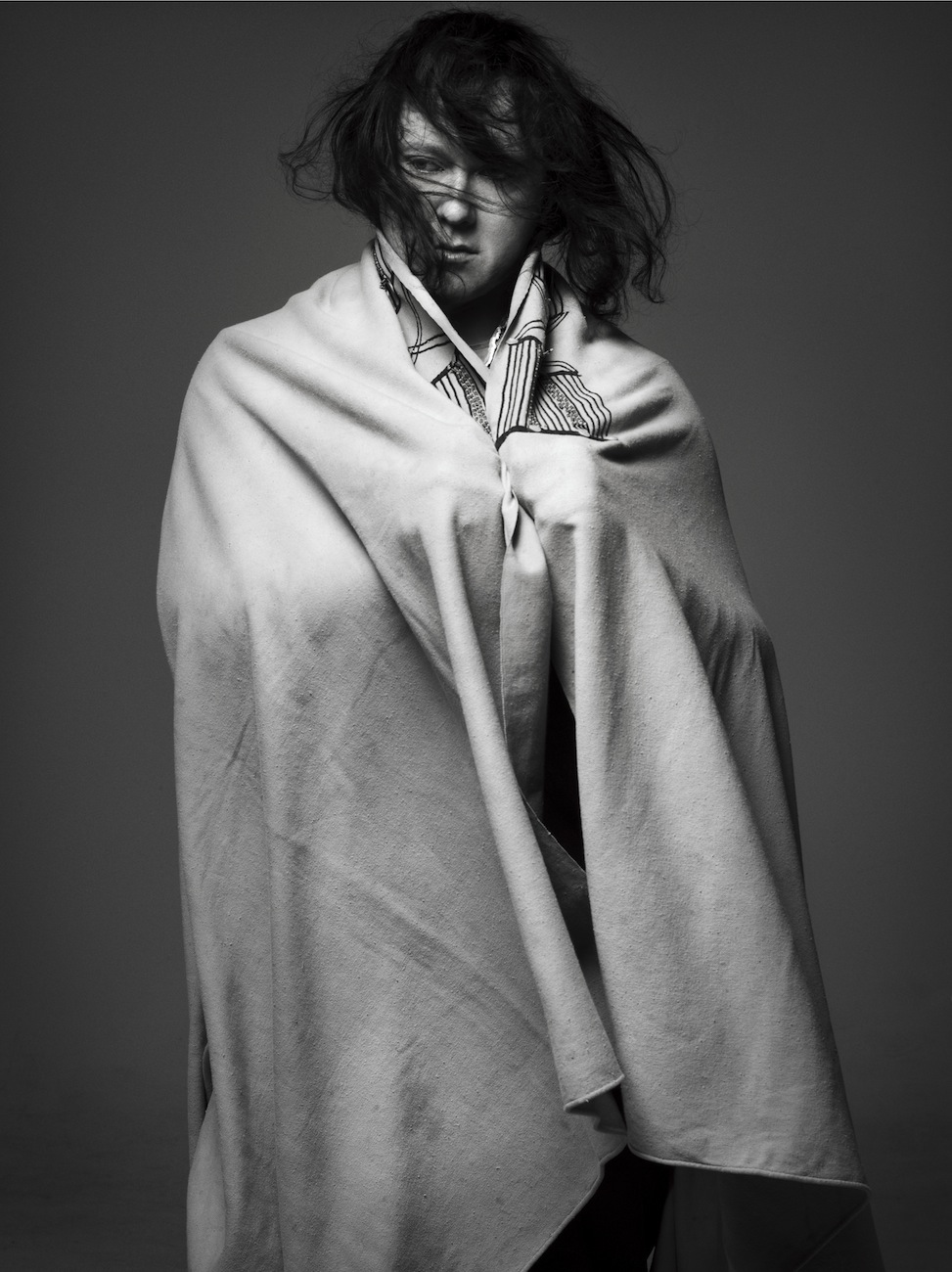

ABOVE: ANTONY. PHOTO COURTESY OF MARK SELIGER

Antony Hegarty is no stranger to critical success. The singer and performance artist, whose second album with Antony and the Johnsons, I Am a Bird Now, won the UK’s prestigious Mercury Prize in 2005, has performed for audiences all over the world and has exhibited drawings at galleries the likes of Palais Des Beaux Arts in Belgium and the Triennale in Milan. This, in part, explains how a pop musician like Hegarty could be commissioned to create a performance by the Museum of Modern Art.

Still, it’s not enough to simply pin the singer’s accolades on an abundance of talent. In conversation, it’s clear that Hegarty is a tireless worker who is constantly looking to push the boundaries both of performance and his own talents, to “explore the creative world,” as he puts it. Thus, it is only a wonder that “Swanlights,” Hegarty’s upcoming performance piece at Radio City Musical Hall, commisioned by MoMA and named for his most recent album, exists until you examine the artist himself.

Anxious to find out more about the show, as well as this month’s exhibition of drawings at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, we spoke to Antony recently about the creative process and finding light within darkness.

JEFF OLOIZIA: “Swanlights” sounds like a really interesting event. How did the collaboration came about?

ANTONY HEGARTY: It’s a collaboration between myself, a light artist from the UK named Chris Levine, and a designer named Carl Robertshaw. It’s basically a concert with a symphony, but then with kind of a visual theme exploring this idea of luminati and light and darkness. It’s inspired by the notion of a quartz crystal within the black side of a mountain, this idea that this kind of luminati could be contained within blackness.

OLOIZIA: That sounds really cool. You’re playing with a 60-piece symphony. Do you find that the preparation for that is different, especially with the different installations, than for a regular Antony and the Johnsons performance?

HEGARTY: Well, I’ve been working with symphonies for the last few years, so we’ve really developed a repertoire of arrangements, and the conductor I’ve worked with, Rob Moose, has become really agile in his ability to work with a symphony in a few rehearsals and bring them closer to me. So it’s something we’ve had some practice with as we’ve been performing with symphonies all over the world in the last few years. And now, it’s wonderful to sort of bring this piece home to New York and to fully realize it like this.

OLOIZIA: Absolutely. Do you come up with most of the arrangements yourself, or is it a collaborative effort?

HEGARTY: The arrangements have been developed the last three of four years in collaboration with several classical arrangers and composers. Initially, I worked a lot with a young man named Nico Muhly in arranging some of my songs for symphony, and then more recently I’ve also collaborated with my conductor Rob Moose and one of the violin player-arrangers that I work with, Maxim Moston. We’ve sort of jointly made decisions about direction and theme and how to utilize this tidal wave of musicians.

OLOIZIA: It all sounds really progressive. Do you feel like you are consciously trying to stretch things artistically, or are you just sort of following your impulses?

HEGARTY: I think that initially, in the ’90s especially, I mostly was performing in the world of experimental theater and presenting my music within the context of plays and tableaux that I was staging at theaters like PS122. At a certain point in the late ’90s, I switched gears and just started presenting my music. And there have been a few forays that I’ve made back toward a more rigorous approach to the visual part of presenting a concert; I’ve just sort of embraced the possibilities of contextualizing a concert within the larger sort of visual experience. I did a piece with Charles Atlas in 2004 for the Whitney Biennial. It was called TURNING. [Charles] is a video artist, and we did that at St. Ann’s Warehouse for the Whitney Biennial in 2004, and then we went on to tour that around Europe in 2006. That was the first time that I really started to reconsider the possibilities of setting a concert within a different kind of performance experience. This is another move in that direction. I first developed this piece from a commission at the Manchester Festival in 2009, and we did it there for the first time. Since then we’ve expanded upon some of the ideas, and we’ve sort of redesigned and expanded upon the set and scaled it up five times for the Radio City, and I’ve developed some new music. It’s a wonderful feeling to bring it back to New York and to share it with my community and my city.

OLOIZIA: It sounds like it’s going to be really amazing. You also worked with The Life and Death of Marina AbramoviÄ?. I’m wondering if you can explain to me why you got involved with that and what you think about her work, and how you could pay tribute to that.

HEGARTY: Well, Marina actually had a big influence on the development of his piece in its fledgling stages when she suggested that I consider—typically, when you light a concert, you go from song to song, and she had suggested considering a larger arc and a larger evolution that spans the length of a concert. For instance, over the length of a concert, the light goes from black to white. And that was really provocative and, in a way, planted some of the seeds for this idea that we’ve developed. Working with Marina is really inspiring. She has a way of harnessing or articulating really essential ideas, creating these almost archetypes… manifesting these very sort of essential notions.

OLOIZIA: That’s a really interesting idea, reconceiving how you light a performance.

HEGARTY: Especially lighting a concert. We’ve come to expect this certain kind of—you know, everyone observes the same protocol, it’s almost like you could just phone it in. Everyone expects flashing lights and special effects, and certainly to some extent, that’s what we’re building off of, is the concert model, but we’re sort of trying to take it somewhere. We’re really pursuing, as I said, this idea of luminati and also of stillness.

OLOIZIA: I also noticed that you are exhibiting work at the Hammer Museum in LA starting in January. Can you tell me a little bit about the works are that are going to be presented there?

HEGARTY: At the end of 2010 I released a book of my drawings called Swanlights, and it’s actually very connected to this piece that we’re doing in January. For the last few years I’ve focused a lot more on drawing and visual work, and the Hammer Museum came and looked at my work and asked me to exhibit some of the best pieces from the last few years. It’s really an honor and it’s a very exciting new development for me. I’ve shown my drawings at some galleries in Europe, but never in an American museum before, so it’s kind of a frontier for me.

OLOIZIA: That’s awesome, congratulations.

HEGARTY: Thanks.

OLOIZIA: Is there one form, your music or your art, that is more dear to you? Or do you think of them as sort of one and the same?

HEGARTY: I think it’s just I’m always vacillating between different mediums, and at a certain point, especially around 2006, after I had done a tremendous amount of performing around the world and singing for hundreds of thousands of people, after that sort of burst of visibility that I had, I found myself retreating into drawing as a way of creating personal space for myself, creatively. You know, I can’t really qualify a hierarchy of value, but I think I just go through different seasons with it. It’s always very organic. I just feel very fortunate to feel like I have a sense of permission to explore. I feel very grateful that for some reason I was raised to believe that I had permission to explore the creative world. I’m very aware of what a privilege that is, because most people don’t grant themselves that permission, and I really think that’s the only thing that separates people that call themselves artists from the rest of the world. It’s suspending self-judgment for long enough to do something expressive.

OLOIZIA: Is that something you feel like you’ve learned, or is just something that was always innate? I feel like most people who create, at least in the beginning, have some sort of fear about failure.

HEGARTY: I don’t think it’s so much that you stop having fear of failure. Really, what separates people that do it from the people that don’t is just one’s ability to take action despite the fear, you know? Or to suspend that fear, or more commonly, the voice of judgment within yourself that says, “This isn’t good enough. You don’t deserve to do this. You’re not worthy. Your expression isn’t meaningful. You have nothing to contribute, just get back to your 9-to-5 job.” It’s not so much that I don’t have all those same voices, it’s more just that for some reason as a kid I was shameless enough that could plow through them for long enough to get something on the table. I’m always feeling excruciatingly embarrassed after a concert; it’s such an unnatural thing to do. On one hand, it’s so unnatural to step in front of so many people and try to do something like that, but on the other hand, it can be such a fantastic boon and such a wonderful ride.

ANTONY AND THE JOHNSONS PERFORM “SWANLIGHTS” AT RADIO CITY MUSIC HALL JANUARY 26.