OPEN BOOK

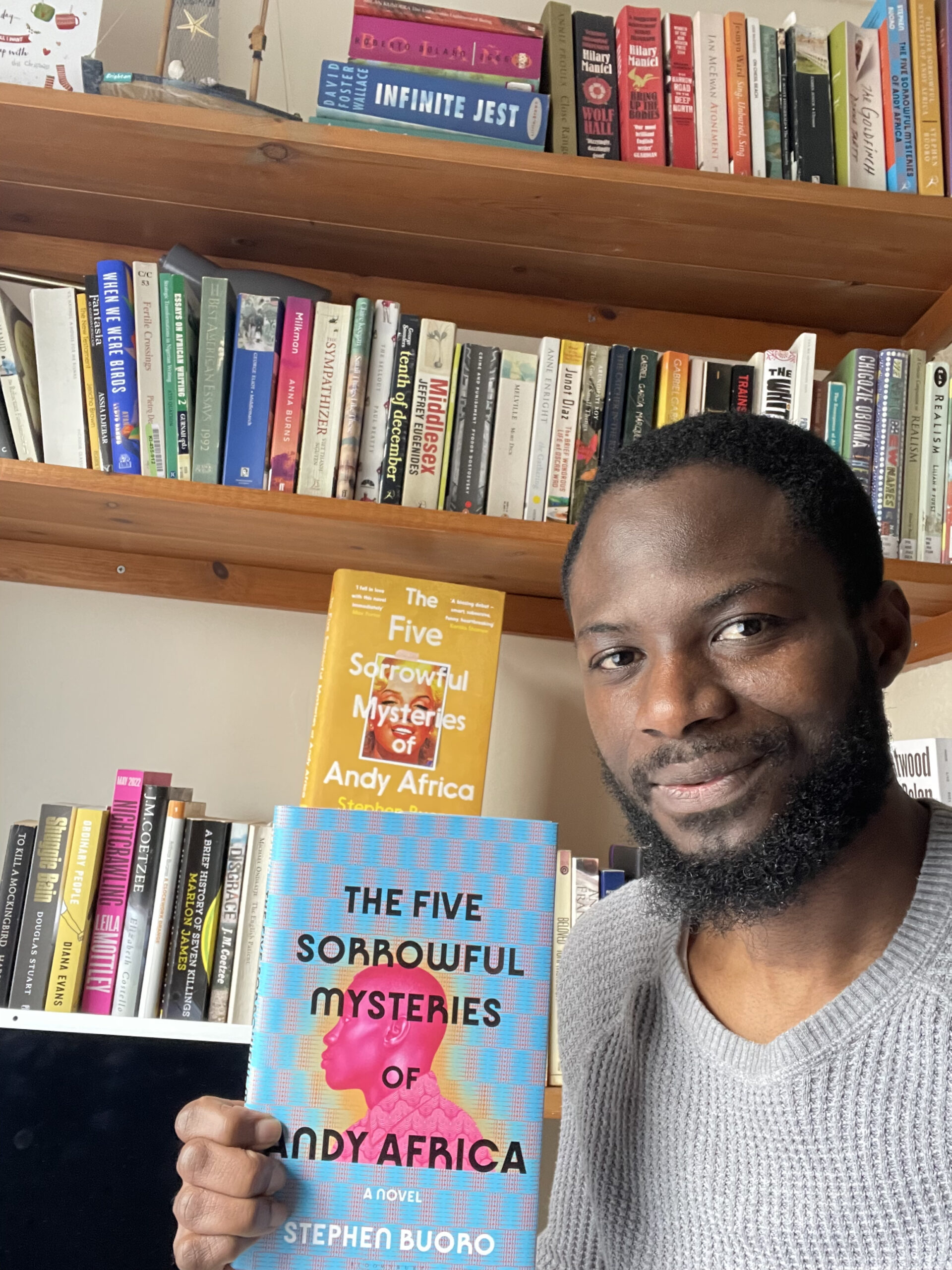

Stephen Buoro Uncovers the Magic and Mysteries of Northern Nigeria

This is OPEN BOOK, a monthly column in which we ask debut authors about their reading and writing habits. Last month, we featured Jinwoo Chong, who recently published the unexpected sci-fi novel Flux. This month, we spoke with Nigerian-British author Stephen Buoro about his bold coming-of-age novel The Five Sorrowful Mysteries of Andy Africa, a bold demonstration of the Booker Scholar’s cheeky and highly personal narrative voice. The novel follows Andrew Aziza (Andy Africa) as he experiences the follies of love and religion in post-colonial Nigeria, where Buoro grew up in Kontagora before moving to the UK to get a PhD in creative writing. The first-time novelist took the time to answer our questionnaire, where he gets candid about writing on the toilet and reminisces about the first “good” bookstore he ever went to.

———

Where do you like to write?

I generally write in my bedroom. I pull the curtains, turn on my desk lamp, sit in a chair. This often puts me in that liminal space between the mundane world and the world of the material I’m writing about. While drafting my debut novel, The Five Sorrowful Mysteries of Andy Africa, I sometimes did things differently. For example, I wrote the first chapter in my living room, the second while sitting on the floor of my bedroom, parts of the third while sitting or lying on my bed. I wrote portions of the tenth chapter in the toilet! Now and then, a change of location helps me to see my work anew, especially while revising. Also, juicy ideas and memories often pop into my head when I’m in the toilet. So I take out my phone and tap away.

When do you like to write?

I’ve realized that the interval between 6.30pm and 9.30pm is when magic is most probable. It’s also when I have the strongest resistance to the terrors of a blank page. So I often compose my first drafts during this period. I write at other times of the day, though. In fact, I prefer revising my work just after waking up (even when my bladder is bursting) or in the early afternoon. So, when everything is going brilliantly, I usually write in the mornings/afternoons and in the evenings.

What’s the first thing you did after you turned in a draft of your novel?

I’m not sure I remember – I’m not great at celebrating. I probably walked to the supermarket or went running or called my mum. Henderson Community Park is close to where I used to live. I go there a few times every year, especially after completing something significant or spending months mostly indoors. So I probably went to Henderson.

Tell us about a formative early reading experience.

As a little child, I didn’t have books around me. My parents only attended primary school. We had just the Bible and a couple of religious texts at home. In fact, I only learnt how to read when I was eight. Still, I don’t think I would’ve become a writer without my mum’s influence. Growing up, I used to have these wonderful conversations with her. I was always amazed enlivened nourished by how she manipulated language. For years, I didn’t have the vocabulary to describe what she did. My mum is incredibly witty and funny. Her wordplay, use of imagery and figures of speech (especially onomatopoeia and allusion), is stellar. I attribute my fondness for intertextuality to her. She would’ve become a writer–and a brilliant one–if she’d had just a little more education. And there are countless versions of her all over my country Nigeria–women who would’ve made/rejuvenated history had they been given the chance. So, as a child, my mum nourished me with language, with the oral text. She made me recognize the beauty, power, transfiguration, and transcendence that words attain in certain permutations.

The last book you loved, and why?

Northern Nigeria is this huge, wonderful region of my country that’s sadly not as buoyant–economically, educationally, literarily–as the South. Writers from this region aren’t as celebrated as those from the South. Also, there are usually fewer literary texts from or about this region being published widely, internationally. Hence, it was refreshing to read Arinze Ifeakandu’s short story collection, God’s Children are Little Broken Things, which consists of nine stories, many set in Northern Nigeria. The collection broadly explores queer love in contemporary Nigeria, a severely conservative and homophobic place. The stories are perceptive, moving, and important. They helped me to see and smell and taste Northern Nigeria in new ways.

The last book that disappointed you, and why?

Now and then I read books that I think are overhyped or overrated, and I just shrug. I try to remind myself that my judgments – despite how clear and true they are in my mind – are simply my personal opinions. It’s hard, but I think it’s the right approach.

Hardcover or paperback? Why?

Most of the books I read as a kid were paperbacks. The ones that weren’t paperbacks were usually volumes of encyclopedias. As a teenager, when I had no novels to read, I would borrow my school’s encyclopedias and read them at home, from one article to the next. So I mostly prefer paperbacks, especially for the ease of reading. But now and then, nothing beats the luxury of a beautiful hardback.

A book you think should be in the canon but isn’t:

I don’t know, and I don’t think about this at all. Or maybe I’m not being honest here. Because what is actually “the canon”? The Penguin Classics? The list of western books on literature modules? What old white men in the chicest unis say are the best works? If by “canon” we mean the works that’ve stood the test of time, then I’ve got nothing to add. We should rather let Time do the choosing. I’d just like to remark that, if we’re pursuing this definition, then it should be noted that the “canon” thus comprises non-Europhone, unwritten texts, such as for example the oral texts (orature) of many marginalised communities/states, such as Nigeria.

A book you think shouldn’t be in the canon, but is:

Based on what I just said about the canon, now, I’m wondering: maybe Time is the true “canon.” I used to think every good piece of art is in some way a study of human pain. Maybe it’s actually a study of time. Maybe that’s why we all want to read something new.

What’s your favorite bookstore(s)?

I don’t think I have one. All the books I read as a kid were either from my school library, friends, or the internet. There were no good bookstores around me. All the stores I knew only had textbooks and a few literary texts, usually ones on the lists of certificate exams – Things Fall Apart, A Grain of Wheat, So Aljannar Duniya – and most of them were pirated. We wouldn’t have afforded these books if they hadn’t been pirated.

Perhaps the first good “bookstore” I ever went to is a Sue Ryder here in Norwich. I really loved the store because the books were clean, well-thumbed, and smelt sweet. (Sometimes new books can seem a bit frightening because they look so lonesome, so unloved, and smell like factories!) Also, the books at Sue Ryder cost just 50p. It was from there that I got my personal copies of some of my favourite books – my Annie Proulx, my Rushdie. I used to visit the store a lot in my first year in the UK, and I’d sigh and wish I could send all the books in the store to my younger self.

What do you look for in a reading experience?

When I pick up a book, I want it to completely possess me. I want to live in it, die, and resurrect in it. While reading, I want to forget who I am. I want to become someone else. Something else. Something more alive. That I don’t know. That doesn’t exist.

How do you arrange your bookshelf?

I do so arbitrarily, intuitively. But there seems to be a thematic pattern. For example, you’d find The Famished Road next to Midnight’s Children, The Palm-Wine Drinkard next to Things Fall Apart, Without a Name next to Beloved.

Have you ever lied about having read a book? If so, which one?

If by ‘reading a book’ you mean ‘reading every single word of the book’, then I’d say yes. For example, as a teenager, I tried reading Lord of the Flies several times. Each time, I couldn’t get beyond the first twenty pages. It felt so weird reading a book with no female characters in it. I was very introverted, and the boys in the book seemed noisy and crazy. The novel has lots of dialogue, and the quotation marks felt like insects hurtling towards me. Now as an adult, the concept, themes, and symbolism of the book sound intriguing, and I look forward to revisiting it.