OPEN BOOK

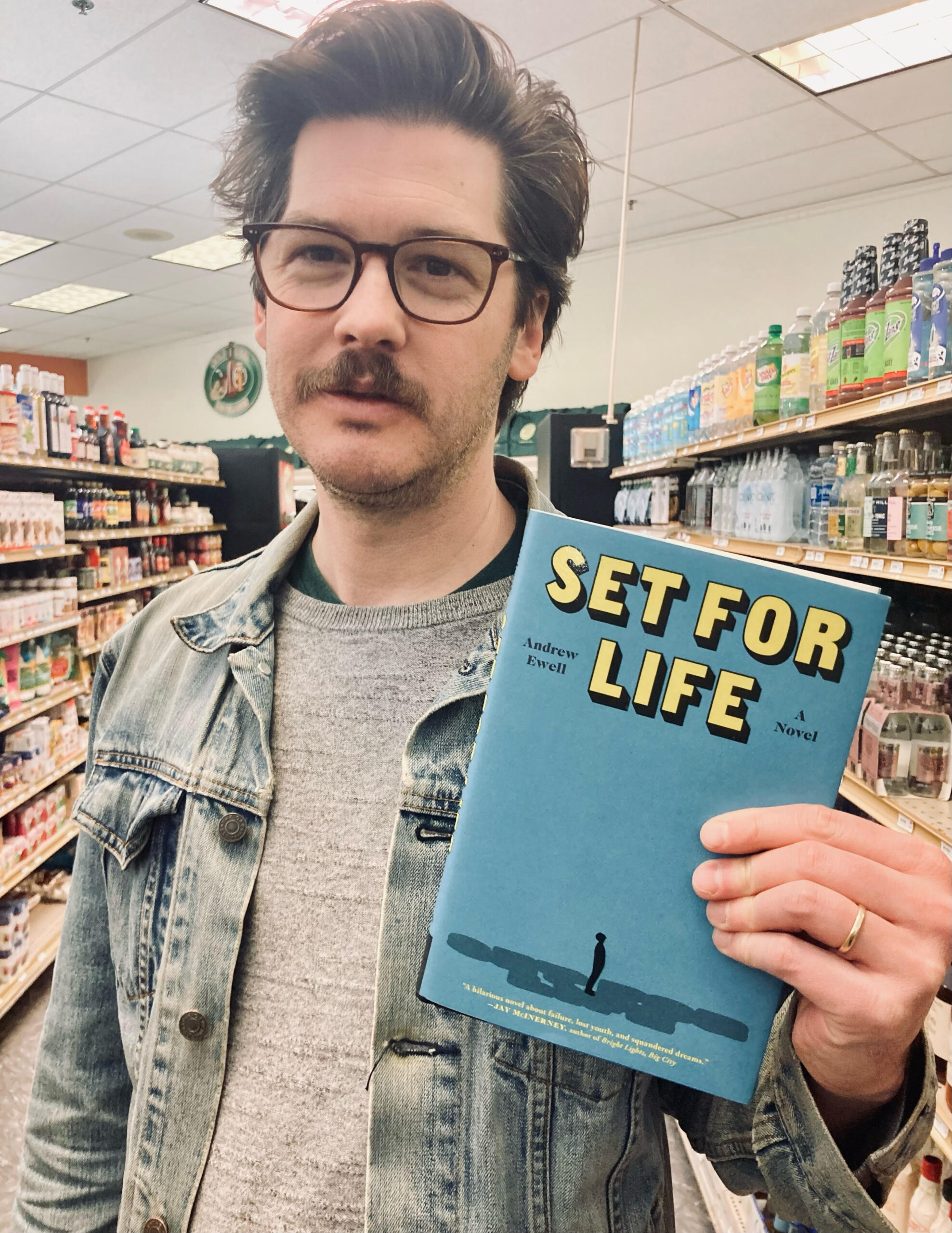

Author Andrew Ewell Doesn’t Believe in Anti-Heroes

This is OPEN BOOK, a monthly column in which we ask debut authors about their reading and writing habits. Last month, we featured Celine Saintclare and her sexy debut novel, Sugar, Baby. This month, we spoke with Andrew Ewell, the author of Set For Life, which follows the unraveling of a writer’s life and the subsequent promise of a bestselling novel born from it. When a dejected creative writing professor’s stopover in Brooklyn leads to an affair with his friend’s wife, the web of entanglements that follow has the potential to give rise to abundant raw material. The kind that, if harnessed, could allow him to transcend the mediocrity of his third-tier college English department existence, not to mention his marriage. After the book’s release, Ewell joined us to debate the existence of “unlikeable characters” and share his favorite literary affairs, real and fictional.

———

Where do you like to write?

I’m lucky to have a very nice home office right now, with a desk set against a window that looks out on a steep hill, a low stone wall, and a rosemary bush. That’s a good spot. Otherwise, I like college libraries, where I usually try to find a carrel on a lower floor, deep in the stacks, where it’s very dark, and you lose track of time.

When do you like to write?

I try to treat it like a job, so I make myself write during the day. But lately I’ve been getting a second wind in the early evening. Perhaps because I’m a little tired and less self-conscious, perhaps because there’s something about night coming on that makes it easier to enter the fictional dream. Or perhaps because those are the hours leading up to cocktail time, and that’s a nice carrot to put on the end of the stick.

What’s the first thing you did after you turned in a draft of your book?

I probably went to work. I was bartending at the time, and most days I wrote until about three, at which point I’d head up the road and start setting up the restaurant for service.

Tell us about three to five books you read while writing your own, and why?

It’s hard to remember, but a glance at my notes from around that time suggests I was rereading Cheever’s journals, probably because I was writing a book about a writer in the throes of a mental breakdown (as Cheever seems to have been through most of his writing life), and also because misery loves company. I also read Robert Hellenga’s Philosophy Made Simple (a sweet and smart little novel). Alfred Hayes’ The End of Me (a haunting portrait of loneliness). Edith Hamilton’s The Greek Way (must have been during lockdown). And Pete Hamill’s A Drinking Life (an excellent stroll through old Brooklyn). Other than the Cheever, however, I do remember consciously avoiding most books about writers, since I happened to be writing one myself and didn’t want to be influenced by what others have said on the subject.

Tell us about a formative early reading experience.

My aunt gave me a copy of The Vintage Book of Contemporary American Short Stories when I was in high school. It was everything to me. Richard Ford, Joy Williams, Denis Johnson, Mary Gaitskill, Robert Stone, Raymond Carver… That book was my gateway to so many of the writers of the 70’s and 80’s that I grew up on and learned from. I think a lot of writers my age have a similar story. In fact, I’m quite certain we can credit the Vintage book with having inspired the multitude of young writers you would have seen walking around college campuses in the late nineties with tattered copies of Jesus’ Son sticking out of their back pockets.

The last book you loved, and why?

I recently read Emmanuel Carrère’s Yoga, about the author’s nervous breakdown following a ten-day yoga retreat. I’m not sure I loved it, but it stuck with me for its supreme strangeness and candor. I like books that feel like a conversation, and Carrère is a very generous conversation partner.

The last book that disappointed you, and why?

I was recently reading Joseph Heller’s Something Happened. It wouldn’t be accurate to say I didn’t like it. But the gender politics have not aged well.

Set for Life is metafiction. What are some of your favorite novels of this genre?

Is it? I guess I am toying with a certain literary self-consciousness, although I never wanted to write anything “metafictional,” at least not in the baroque style of a Barth or a Coover. That said, there is a sort of writerly self-awareness—an admission, anyway, that a story is being told—which I do enjoy. Lorrie Moore’s Anagrams is a good example. William Styron’s Sophie’s Choice, as well. Much of Tim O’Brien, too. And pretty much all of Philip Roth’s “Roth” novels.

Would you describe the protagonist of Set for Life as an “unlikable character” or an “anti-hero”?

Some readers will call him “unlikeable,” but I don’t have much use for that word myself. Is Emma Bovary “likeable”? How about Melville’s Bartleby? Or Dostoevsky’s underground man? To ask that fictional characters always be pleasant, friendly, and virtuous is the wrong way of thinking about literature. We don’t turn to fiction for comfort and affection, but to be shown the various ways in which life is lived. To limit the scope of that project to only what is good and right would leave us with very little in the way of interesting, thought-provoking, or entertaining stories. My character is lost, out of touch with himself and society, and he stumbles through various mistakes before eventually finding something close to understanding or acceptance. It seems to me that’s what makes him human.

Hardcover or paperback? Why?

It’s nice to see a home library full of well-kept hardcovers. They have a confidence to them, a degree of authority. But paperbacks are better for traveling and easier to hold, if less august.

A book you think should be in the canon, but isn’t:

Can I say the entire oeuvre of John L’Heureux? One after another, he wrote intelligent, funny, and morally complex novels in pitch-perfect prose. For economy of language and clarity of thought, he can’t be beat.

A book you think shouldn’t be in the canon, but is:

The Great Gatsby deserves its place in the canon, without question, but I think it’s hard to enjoy after the age of forty—and even that may be stretching it by about a decade.

How do you arrange your bookshelf?

Alphabetically. Is there another way?

Set for Life is about an affair. In your opinion, what’s your favorite famous literary affair?

By “literary,” do you mean fictional? Or are we talking about a real-life affair among literary people? If it’s the former, then where do I begin? There’s Anna and Vronsky, from Anna Karenina, of course. And the weird tryst at the center of Chekhov’s “The Lady with the Little Dog.” Then there’s Drenka and Mickey, from Sabbath’s Theater. And nearly everybody in The Good Soldier. But if you’re talking about the other kind, then I submit Nelson Algren and Simone de Beauvoir—an odd couple if ever there was one, although there’s no doubt they enjoyed something like love between each other.

What’s your favorite bookstore(s)?

As an author trying to sell books, I probably shouldn’t say this, but I love used bookstores. I like finding books that are out of fashion, that no one’s talking about anymore, that never got a chance in their first life. A used bookstore is also one of the few places left in the era of the algorithm where you can still browse and discover things for yourself.

What do you look for in a reading experience?

I want to see the world through the author’s eyes. I want to know how he or she makes sense of things. I want a good conversation. And I want to sit back when it’s done and feel that I’ve learned something—about myself, the author, and life in general.