LIT

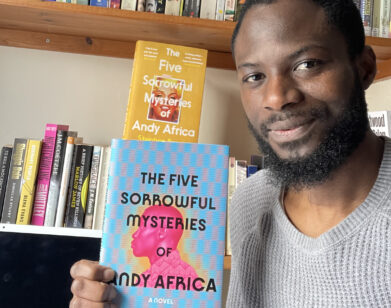

In Her New Story Collection, Author Pemi Aguda Invites Readers For a Haunting

Pemi Aguda’s stories stay with you long after you’ve read the last word. In her fictional world, toxic energy seeps into a newborn through breast milk, chaotic behavior is the sole remedy for recurring pimples, and an unhappy woman morphs into a strange bird. Such bizarre scenarios come to life in Aguda’s debut collection of stories, Ghostroots. Set in a mystical version of her native Lagos, these tales merge the supernatural with the mundane and imagine how the horrors of womanhood are passed down through generations.

Growing up with limited knowledge of her own family history, Aguda reflects on what it means to not know who or what came before you. Ghostroots, she explains, is her way of exploring the ways in which one’s history lives with them and manifests in ways they may not realize. Between conflicting time zones, I got on Zoom with the author to discuss the appeal of being haunted, fielding comparisons to Nollywood films, and the inspiration she finds within the wild world of Lagos.

———

MARRIS ADIKWU: It’s cool that we’re doing this interview on International Women’s Day.

PEMI AGUDA: Oh, yeah.

ADIKWU: You tend to write complex women into your stories. I found out about your work right after you won the Writivism Prize for “Caterer, Caterer,” and I remember being so fascinated by how you infused humor into what would’ve been such an otherwise gory story. So, I have to ask, what’s behind your fascination with haunting stories?

AGUDA: Do you consider “Caterer, Caterer” to be a haunting story?

ADIKWU: I guess so. It was pretty funny, but it also had some haunting parts.

AGUDA: I don’t disagree. I love a good haunted story. I love a good ghost story. Actually, I was telling my university students the other day that almost every story could be read as a haunted story. As much as we’re haunted by ghosts or our ancestors or evil, we’re haunted by memory, too. We are haunted by repressed emotions, by the decisions that we don’t make, and I love that the mood of a story can express what the character cannot express. So, when I start writing, I just naturally go in that direction.

ADIKWU: How much do you actually believe in the presence of the supernatural in real life?

AGUDA: Oof. In real life, I keep telling people that I am waiting to be haunted. I want to be haunted. I would love a moment where my whole reality feels shifted, where a “before and after” mark is introduced: before I saw a ghost and after I have seen a ghost. I have not experienced ghosts personally, but perhaps my stories are an invitation to them.

ADIKWU: What role does humor have in your work?

AGUDA: Actually, I don’t think about humor a lot when I write. When people tell me that something was funny, it’s always a surprise to me. I don’t necessarily consider myself a funny person. If there’s any humor, it’s always inadvertent as opposed to deliberate. But I have friends who are really great storytellers, and the way that they frame sentences, the way they frame narratives and keep me asking, “What happened next? What happened next?” I try to assimilate that and have that propulsion reflected in my work.

ADIKWU: Since “Caterer, Caterer,” you’ve gone on to tell stories with mystery, horror, magical realism. You’ve been able to master the art of combining elements of the supernatural with mundane reality. How has your work evolved?

AGUDA: That’s a great question. I think that what I have been reading has changed over the years. The things I’m reading have changed, and I’ve grown up, too, moving across the world, meeting new people—all of these end up changing fiction, right? As I’ve changed, my fiction has changed, and over time my idea of what is good fiction has kept broadening and broadening.

ADIKWU: There is so much fiction from Nigeria centered around mystical themes, and they’re told in very elaborate ways in film and in prose. How have you been able to develop your own distinct style?

AGUDA: When I was 20, I wrote a short story, and one of the comments was, “Oh, wow. This feels very Nollywood!” I was very upset, and it took me a long time to understand why, at the time, I didn’t think that that was a compliment. Even though I now think that there’s space for the melodramatic and for exaggeration, I am more attracted to subtlety. Especially when introducing elements of the supernatural, it’s important that the reader feels grounded. Does that make sense? So, I believe in subtlety, and I believe in a grounded entry so that when the world shifts, it feels both inevitable and surprising at the same time.

ADIKWU: Let’s talk about your upcoming story collection, Ghostroots. Congratulations, by the way. The stories are set in a re-imagined version of Lagos, where characters fight for freedom from ancestral ties. What was the inspiration behind these stories and why Lagos specifically?

AGUDA: Well, why Lagos is a simple answer. That’s where I grew up. That’s what I know. I spent most of my life in Lagos. It’s a wild city, but it truly inspires me. As for what inspired the stories? You talk about the stories being about people who are vying for distance from ancestral ties. I was one of those people who did not know much about my family history growing up. My parents didn’t think it was necessary for us to know some things, or go back to their villages. Over time, I got really jealous of friends who could trace their ancestry back, I don’t know, seven generations. A friend of mine was calling her great-grandmother’s “Oriki” and I felt really envious of that connection. So, some of these stories are writing into that gap, that absence, and asking what it means to not know who came before those who came before you. But on the other hand, I find myself doing and saying things that are so reflective of my mother and my grandmother, so even though I don’t know this history personally, it feels like this history is living with me in ways that I might not realize. I think that some of these stories are written into that unknowing.

ADIKWU: That makes sense. What’s next for you?

AGUDA: The project I’m currently working on is not very magical, actually. If there’s anything supernatural, it’s more in language than changing realities. But it’s still about women. I am thinking a lot about Christianity and the boxes that young women are put in because of the culture of Christianity in Nigeria particularly. Specifically, what situations like that can do to a young woman’s sense of self. That’s what I’m thinking about.