IN CONVERSATION

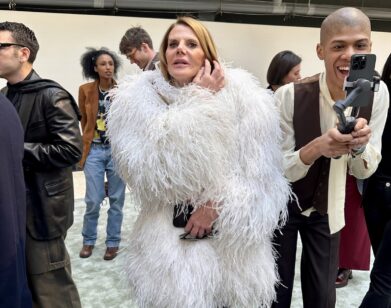

Natasha Stagg and Tish Weinstock on Goths, Girlhood, and Grand Rapids

When I was asked if I wanted to interview Natasha Stagg, the crown jewel of New York’s literary scene—or as writer Delia Cai called her, “the lit It Girl’s favorite lit It Girl”—for a piece on her brand new novel, Grand Rapids, it was an instant, obvious yes. Having been stalking Stagg parasocially for a while now (we’ve exchanged a couple of emails and WhatsApps to date), at last I would finally have an audience with her, albeit one mediated through a screen, the Atlantic Ocean stretched between us.

Being the world’s slowest reader and arse-crack deep in fashion month, I was worried I wouldn’t be able to get through Grand Rapids in time. To make matters worse, I was reading it via PDF on my heavily cracked iPhone, which meant having to swat away a flurry of notifications like flies, with each buzz daring my ADHD brain into distraction. But I wasn’t distracted at all. And that’s because Stagg writes with such lucidity that you can’t help but be swept away with it. If you’ve read her previous works, like Artless or Sleeveless or even her Substack, “Selling Out,” you will know what I’m talking about.

But back to Grand Rapids. Instead of putting her usual, unforgiving lens to contemporary culture, her latest offering takes us back to the early naughts. Post-9/11, pre-Instagram. Loosely based on her own experience, it follows 15-year-old Tess as she explores the freedoms and frustrations of coming of age in American suburbia. As someone who didn’t grow up in the Midwest, but rather West London, I suspect our experiences of girlhood were somewhat different, and yet there were many commonalities: navigating one’s identity through bottles of hair dye; falling for bad boys; free bleeding on random furniture; the agony and ecstasy of youth; the pain of grief; the embarrassment of it; making out with your girlfriends; and the desperate attempt to get as obliterated as possible by any means necessary. Here, we speak about growing pains, old people, and the perils of comparing yourself to others on Instagram, something she sensibly doesn’t do. Hopefully, we can do it in person next time.

———

TISH WEINSTOCK: I’m so happy to be doing this because I’ve still yet to meet you in the flesh.

NATASHA STAGG: I know.

WEINSTOCK: So this is one step closer.

STAGG: I’ve always wanted to meet you.

WEINSTOCK: Me too. How are you, where are you, and where have you been?

STAGG: I’m in New York. I’m in my apartment. It’s raining.

WEINSTOCK: Nightmare.

STAGG: How’s Paris? You just got there?

WEINSTOCK: I just got to Paris. I was in Milan. I went for Gucci and actually it was great, the film.

STAGG: I liked it.

WEINSTOCK: I was obviously dreading attending a fashion film premiere because I was like, “Oh god, it’s going to be a bit much.” But it was very funny. Let’s talk about your brilliant new book though.

STAGG: Oh, thanks.

WEINSTOCK: What was that whole writing process like? Because you’ve been working on it for a while.

STAGG: I was kind of off and on working on it.

WEINSTOCK: Right.

STAGG:I mean, I shouldn’t even say that I started it a long time ago because the way I write is just whenever I feel like it.

WEINSTOCK: Yeah, that’s nice.

STAGG: So many writers have these schedules and they make themselves do it and I’m like, “If I made myself write, I wouldn’t like it.” I don’t think I would like the writing either.

WEINSTOCK: Well, you’d be imprisoned by it.

STAGG: Yeah. And I write for a living too. I work for brands and I’ve written for magazines a lot and it’s a job and those stories take so much out of me and I don’t want to be doing them sometimes.

WEINSTOCK: It’s like homework.

STAGG: Yeah, it has to be enjoyable. So that’s why it comes so slowly. I have to have time off of writing for work to get back into writing for fun.

WEINSTOCK: And where did the seeds of this book come from?

STAGG: So I partially grew up in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and those were some formative years in high school. I went to college in Michigan too, but this story just takes place over one summer. It jumps around with the character looking back from a future version of herself. And I mean, none of this is real life, but it’s set in a time and a place that I actually lived in because I can only trust myself to write about something that I’ve seen.

WEINSTOCK: What I loved about it was this juxtaposition of girlhood and that amazing boundless freedom. It’s very innocent and naive and romantic, but also there’s an element of danger. Like, they’re getting completely obliterated, making out with their girlfriends, dyeing their hair. It’s all the tropes of growing up as you navigate your identity and I got quite nostalgic reading it. But then that was cut in with these horrific images of old people in the old person’s home and I was like, “No.” There’s this image of freedom and hope and the possibility of the future, and then there are people who are trapped in their bodies, their memories, their wheelchairs. Was that an important contrast for you to make?

STAGG: I mean, it was based on a real job I had as a teenager. So when I look back on my own youth, it’s such a vivid image. I can see myself so young, and of course not knowing how young I was, thinking of myself as an adult. But I was a teenager going to work at this nursing home being like, “I’ll never be like this.”

WEINSTOCK: That really comes through in the writing. In a Hollywood version of this story, they’d be like, “Oh, Mrs. W, how are you?” And then the protagonist would have an amazing relationship with the old person and they would learn something about themselves because of it. But actually, when you’re young, old age is something that’s so alien and a little bit repulsive.

STAGG: I’m terrified of aging. I’m not doing anything to put it off at all, but that’s just because I’m cheap and scared of doctors. But I imagined that I would never be as old as I am. I am still doing the math of my birth year. There’s no way that I’m almost 40. It doesn’t make sense to me.

WEINSTOCK: You don’t look it, so that’s good.

STAGG: Thank you. But yeah, it’s definitely a thing I was thinking about when I was writing this because it’s from the perspective of someone much younger than me thinking about her own much younger days. So I might as well be in that nursing home.

WEINSTOCK: [Laughs] Help! It’s interesting because when you are Tess’s age, you think you are fucking invincible and you think you’re an adult, but you’re not. You are in this liminal state where you’re too young to do anything and you’re living at home and you’ve got all these limitations on you. But then the older you get, you think back to you at that age and you’re like, “Oh my god, I was a baby and totally clueless and completely mad. How did I get away with doing all that crazy shit? Why wasn’t I being parented properly?”

STAGG: We probably had such different youths, but there was that idea of being as goth as possible without presuming that you are. There’s also this barrier of entry there. If you’re still living with your parents, are you really goth? Then looking back you’re like, “Oh, everyone was living with their parents.” The goth thing about it feels like an aspect of youth that can only be really viewed from hindsight.

WEINSTOCK: Had you experienced death growing up?

STAGG: Yeah, kind of a lot. My mother died when I was a teenager.

WEINSTOCK: My dad died when I was five. There is this tension of how to talk about death and when you are young and someone dies in your life, because you get treated like you’re special and different because it’s such a sad tragedy that’s happened. You are not only experiencing grief, but it defines you in a way. That was my experience, and certainly in reading what you wrote.

STAGG: Also, you look back on the way you were behaving and it’s surprising how all of your behaviors are played out all at once. You think of yourself suffering a tragedy, but then you see photos of yourself having a great time.

WEINSTOCK: Yeah. You try drugs for the first time, you lose your virginity, your body changes, you get breasts, you get your period. When she free bleeds on the sofa I was like, “I’ve been there.” These huge things happen, but they happen really quietly and they happen in a boring way.

STAGG: Yeah.

WEINSTOCK: What was the experience writing? Was it cathartic? Did you learn anything about yourself?

STAGG: It’s cathartic in some ways to put everything down that you think might be an interesting part of a story and then getting rid of a lot of it. That’s sort of my process. Somebody else asked me if I was a fan of these super dramatic youth movies like Kids and Gummo. And of course, when I was a teenager, I was watching every movie where something disgusting and tragic happens to a teenager. But then I also grew out of that genre. So a big part of me writing the book was trying to parse what a taste does to a memory. And if you’re looking back at something that you used to do, how much was that informed by what you liked to do and listen to and watch?

WEINSTOCK: What I thought was interesting was a departure from writing about the here and now. There was a glaring lack of social media, obviously because it was a different time, but it felt much more detached. Now we’re so reminded of where we are at all times and everything that’s happening in the world and it was interesting to be immersed in this world that was a bit vaguer. It makes me wonder what it’s like for kids growing up now, where everything’s on Instagram or Substack.

STAGG: I think about that all the time. And you probably think about it more because you have kids.

WEINSTOCK: Yeah, I’m scared for them.

STAGG: I mean there’s not a monoculture, there’s not a movie that everybody watches. It’s more like these niche interests that inform people’s behaviors.

WEINSTOCK: When you write, when you inhabit this other voice as your protagonist, Tess, what is the process of getting into her mind?

STAGG: It always starts with some version of myself, and then I can separate it. When I’m writing fiction, it’s pretty easy to forget that anything that comes into my mind might have come from an actual experience. I’m just telling myself that I’m imagining all of it. I think about the other books that I’ve published and they sort of bleed into each other now. I don’t know where one started and left off and I’ve definitely had an experience where I’m telling somebody a story and they’re like, “You wrote this.” And I’m like, “Oh my god. I thought it was just a personal anecdote that I can continue to tell forever.”

WEINSTOCK: You kind of can. It’s your material.

STAGG: Right, but I don’t know.

WEINSTOCK: One line I wrote down: “The way women grow up is into each other.” I thought that was very interesting. What is your experience of that?

STAGG: Somebody else asked me about this line and I was like, “Oh, what did I mean?” [Laughs]

WEINSTOCK: You’re like, “Why did I write it?”

STAGG: My way of thinking about that is just that women take so much from each other. Probably more than boys, we’re constantly socializing and doing this thing where we’re comparing ourselves and also giving each other advice and doing each other’s makeup. So we’re learning from the other person’s experiences, good and bad. I mean, I’m probably super aware of this being a twin, the way that I could have turned out very differently if I didn’t have a double that I was constantly reacting to and maybe defining myself by.

WEINSTOCK: Yeah, you’re constantly redefining yourself against your female friends around you because when you’re younger, you’ve got your parents or whatever figures of authority. But then when you leave home, you’re constantly defining yourself in opposition to the closest people in your life.

STAGG: Whereas with men, I think they are told not to think as much about their identities online. But who knows?

WEINSTOCK: Yeah. Last question. I thought that one of Tess’s central preoccupations was this idea of being cool. Not that she necessarily wanted to be cool, but this idea of liking the right things and having the right taste and shaping your identity, that’s always very central to the experience of youth. If you’re not cool, you’re a freak. But being a freak has its own coolness encoded in it. So I wanted to know what you thought it meant to be cool in this age. And if you are chasing that mirage of cool, can you ever be cool?

STAGG: Good question. I think there’s stuff that’s cool, but it’s definitely a thing in the art milieu to be like, “Nothing’s cool anymore.” But I want to push back on that because that’s just what uncool people say. There are cool things happening. I don’t think I’m the authority on that. I’m not going to go to a festival probably ever again. It’s just like, there are things that I love to read about other people doing—like on Substack, for example—where I’m like, “That’s so cool. You’re having such a good time. I once did that and I loved it too.” But it’s still cool to be less and less online, maybe. And not even being completely offline, but showing yourself online to be a bit less online than you are.

WEINSTOCK: No, I agree. That’s a very good answer. It’s rejecting that whole, “I should just get off Instagram.” That’s why I like Substack.

STAGG: Yeah.

WEINSTOCK: I just find that it’s helped me to reengage with the world instead of just fully existing online or just consuming online stuff. I’m like, “No, I should go and see something or watch something or read something.” And it makes me more present in the stuff that I am doing.

STAGG: Right. Like what you were saying about Instagram, the whole point of it was to induce jealousy. If advertising takes anything over, then you’re immediately going to get swept up in that wave of advertising oneself. Even if you’re resisting, it’s not possible because then the actual shape of the platform changes and you’re surrounded by advertisements and you feel like you need to compete. But if you’re like, “This is a long form blog,” you’re resisting that thing that you’re leaving behind.

WEINSTOCK: True. Well, thank you for speaking to me.

STAGG: Yeah, thanks for this, Tish.

WEINSTOCK: Bye.