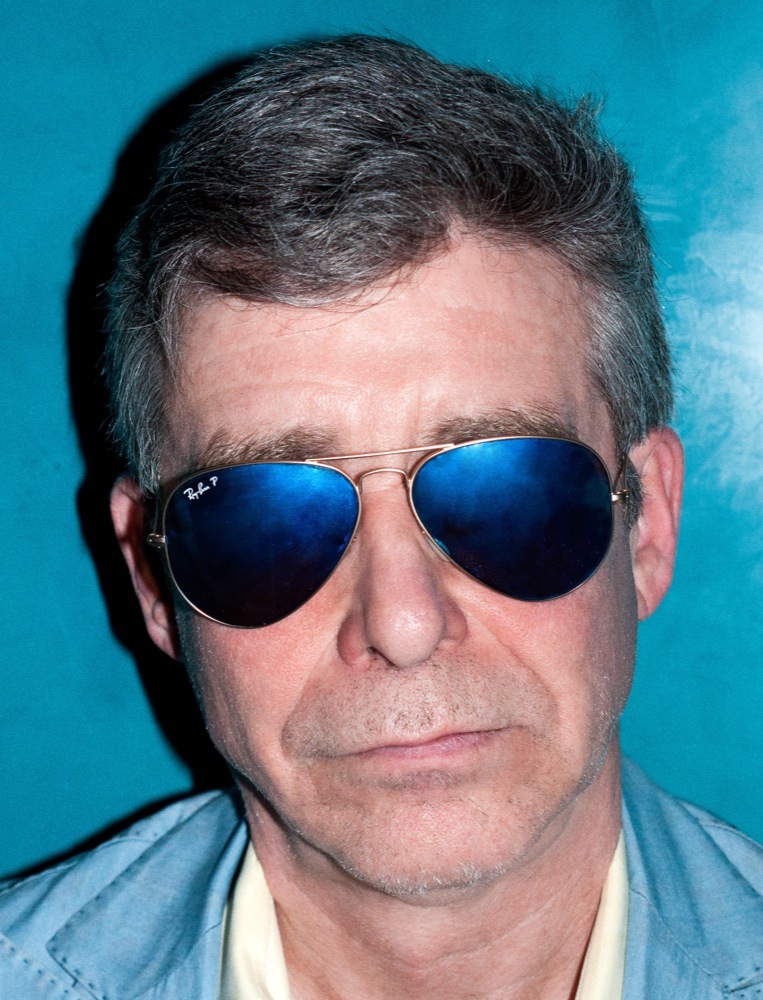

Jay McInerney

In order to decide to stake your well-being on something as precarious as writing fiction, you have to be a little bit reckless. Jay McInerney

Right smack on the first page of Jay McInerney’s new novel, Bright, Precious Days, is an ode to literary Manhattan, “the shining island of letters,” and the iconic books, publications, and authors who gave that shine its stadium wattage. The Paris Review and The New Yorker are mentioned. So are Kerouac and McCarthy and Mailer. And The Great Gatsby and The Bell Jar and Underworld and The Catcher in the Rye, which, as McInerney phrases their power over non-native readers, “spoke to them in their own language.” What’s clearly missing in this list, to anyone of my generation who dreamed of this shining island as a kid while living in the duller provinces of America, is McInerney’s own inclusion to the shelf of great New York books: Bright Lights, Big City. It’s hard to imagine a novel that had more cultural and social impact on the city than this 1984 paperback novel that traces the glittery slide of youthful overindulgences. Call it a sort of enhanced roman à clef from a Connecticut-born transplant who wrote it while enrolled in the graduate writing program at Syracuse University. Or call it the dark, masterful literary version of a New York nightlife brochure. But some 30-odd years later, McInerney’s second-person narrator (the most successful use of “you” in literature, I’d argue) still holds up with disturbing and efficient provocation, as he guts the city that is gutting him. Has there been a finer New York City novel since?

If there has been, it may be McInerney’s other novels that lead in the rankings. The hard-partying female aspirant in 1988’s Story of My Life is an under-recognized masterpiece in voice and tone that seems to have predicted the current self-obsessed lifestyle as finely as his pal Bret Easton Ellis did maniacal celebrity culture in Glamorama. McInerney has always been an urban explorer and his quest isn’t so much celebrating as dissecting the mutant variations of the American Dream that define his time and place. McInerney’s time is the affluence of the recent present and his place is the Manhattan taxi grid. He introduced the characters Russell and Corrine Calloway, an attractive married couple living in Tribeca who are both conscientious and socially conscious, in his 1992 novel Brightness Falls (it might not need mention to note the use of the word bright throughout McInerney’s career). The novel tracked the travails of 1980s city optimism right up to its Black Monday demise. McInerney revisited the Calloways in the elegiac 9/11 novel The Good Life (2005). Older, wiser, the Calloways were caught between their own survival and the survival of a city that no longer appeared so imperishable. This month, with the release of Bright, Precious Days, McInenery returns to the Calloways in the mid to late 2000s, where they’ve hit the once-unthinkable age of 50 and the equally once-unthinkable realization that the city itself has changed—no longer a bastion of freedom and bohemianism and no longer hospitable to a meager six-figure family income. Russell, an editor who still believes in the value of art and literature, is fighting to keep his publishing house solvent and banks his hopes on a reckless young writer and a reckless older memoirist with a questionable war story. Meanwhile, Corrine, the head of a food charity, reignites an affair that began in the days after 9/11.

In Bright, Precious Days we have gotten very far from the Manhattan of Bright Lights, Big City. McInerney’s characters are now treated to backdrops that include a rich socialite’s uptown townhouse where a Liger has been retained to entertain children and hotel lobby bars filled with “the unmistakable whine of privileged white men with the blues.” McInerney is not a fantasist; even in all of its posh surroundings, he’s willing to concede the realities of the city and the rickety Wall Street engines that run it. If we readers don’t relish every second of the New York on offer in Bright, Precious Days, then, well, we can drown ourselves in the nostalgia of late 20th century novels. But as the title suggests, some of the “brightness” still exists and is perhaps more precious for being less abundant. After all, the cover of Bright, Precious Days mirrors McInerney’s 1984 novel cover with its picture of Tribeca restaurant the Odeon. Some things, against all odds, have endured.

Does the Jay McInerney who wrote Bright Lights still exist? At 61, McInerney is keenly aware that his first novel is an unshakeable shadow that follows him, as much as The Great Gatsby is forever linked to our understanding of Fitzgerald or The Bell Jar to Plath. The danger of success is often its endurance. McInerney still lives in downtown Manhattan, long after so many of his early peers have moved out. And anyone who has met him can attest to the feral boyishness in his eyes and smile. But I think McInerney has managed to do what few writers, or other cultural figures for that matter, have: he’s become both a generous literary elder (McInerney is often among the first to promote a young, untried novelist, sticking his neck out when so few are willing) and he has remained a relevant and dynamic chronicler of New York’s mercurial rises and falls. In a hundred years, historians may have no better method of observing the cultural and economic tides of New York than by reading McInerney’s output.

This past May I met up with the novelist—and moonlighting wine expert—for lunch at the Italian restaurant Il Cantinori not far from his apartment. I was going to hand him the wine menu and tell him to go crazy, but McInerney was co-chairing the PEN America literary gala that evening and I was busy trying to remember exactly what kind of bird a poussin was from the list of entrees. I ordered coffee. He had water.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: The first pages of your new book are an ode to the days of New York City as a beacon of literature—particularly for all the kids scattered around the country who want to come to New York to be poets and writers. “Once, not so very long ago …” it begins, implying that it is no longer. Is this a veiled critique of the power of the current publishing world?

McINERNEY: No, not really. To tell you the truth, that first chapter came very late in the game—maybe in the third draft. And publishing has always been part of the world of New York that I write about. Starting with Brightness Falls, Russell Calloway is an editor, and he remains a literary figure through his adult life. I guess I’ve always been interested in building in a layer of self-referentiality in these books. Although, of course, when I wrote the first book, I had no idea it would eventually become a series.

BOLLEN: You didn’t walk away feeling like there might be a sequel for Russell and Corrine?

McINERNEY: When I wrote Brightness Falls, I didn’t think I’d live past 40! [Bollen laughs] I wasn’t making plans that far ahead.

BOLLEN: But you take up Russell and Corrine again during 9/11 in The Good Life. You survived the decade and the attacks, and so did they.

McINERNEY: As someone who wrote about contemporary New York, there came a point after September 11 where it seemed to me that I had to figure out a way to engage this subject. And at some point I thought of Russell and Corrine and their friends. The event itself was so massive, I thought I had to bring it down to a domestic scale. I realized I already had these characters through which I could focus the story of the most catastrophic event in New York’s history—unless you possibly count the draft riots of the 1860s. But this was pretty much the Big One. And by the time I finished The Good Life, I figured I would definitely revisit them again. I knew I was going to go on with their story.

BOLLEN: I suppose when you know you’re going to keep up with them, the rules change. No killing off the main characters, for example.

McINERNEY: If I had known I was going to write a sequel from the get-go, I probably wouldn’t have killed off one of the main characters in Brightness Falls. Although the writer, Jeff Pierce, keeps coming back.

BOLLEN: He haunts the new book. His novel from the ’80s has gained a cult status among young readers. And there is a rather hilarious line you have about how he’s been resurrected from his previous fate as merely “associated with the period of big hair and big shoulder pads.” I wondered if writing about Jeff was a way for you to reflect on the cult of the ’80s novelist. Was Jeff in any way an alter ego?

McINERNEY: Definitely. Jeff was kind of my alter ego. At the time of Brightness Falls, I thought by killing that character off, I could sort of kill that part of me off, too—the certain aspect of myself as the bad-boy writer of the ’80s. I think that was in my mind.

BOLLEN: Before I ask you about the ’80s, are you sick of fielding questions about the ’80s?

McINERNEY: No, it’s fair game. My characters came to New York in the ’80s, when they were in their twenties. So inevitably it’s a vivid time for me, as is any place when someone is in their twenties. And in this novel, I have flashbacks to the ’80s. New York in the ’80s has achieved this semi-mythic status.

BOLLEN: I think that’s because it was the last time New York was un-self-consciously the capital of the world and culturally relevant.

McINERNEY: I get quizzed a lot by young people about what New York was like back then.

BOLLEN: And what do you usually tell them?

McINERNEY: It’s a very long story. There’s not a short answer. But it was fun.

BOLLEN: In the book, Russell is the editor to a young rising fiction star Jack Carson. Russell has a heavy thumb in editing Jack in the way editor Gordon Lish notoriously did with Raymond Carver. You studied under Carver. And when I was reading this novel, I looked up Carver again and re-realized that he was only 50 years old when he died of lung cancer. In my twenties, that seemed sufficiently old, but now that I’m 40, I can’t believe Carver died so young!

McINERNEY: Yeah. Most all of the writers I admired when I was in my teens and twenties died young. Fitzgerald lived the longest. He was 44. Dylan Thomas was 39. And then once you’re approaching 40, you suddenly think, “Well, maybe I would like to live longer than Fitzgerald or Thomas.”

BOLLEN: Or Carver. Even for a smoker, that’s extremely young. He must have been voracious.

McINERNEY: He was a heavy smoker. It might have been an AA thing, too. Drinking leads to smoking. But the only thing worse for smoking than drinking is quitting drinking. [Bollen laughs] Because then it’s the only thing you can do. AA meetings are one big cloud of smoke. A lot of caffeine and a lot of nicotine.

BOLLEN: How did you meet Carver?

McINERNEY: I met him probably in 1981. He was visiting New York to give a reading. And he was also visiting his editor, Gordon Lish. He was having a lunch with his future publisher, Gary Fisketjon, who is my best friend. And after lunch, he didn’t have anything to do before his reading at Columbia that evening. Gary knew I was a huge Raymond Carver fan, so he called me up. I was unemployed at the time because I’d just been fired from The New Yorker as a fact checker and was just lying around my apartment. So Gary said, “How’d you like to entertain Raymond Carver for the afternoon?” I thought he was joking. But about 20 minutes later, my buzzer rang and there was a big bear of man at the door.

BOLLEN: I love that Carver was actually up for some strange kid entertaining him for the afternoon.

McINERNEY: Yeah. So he sat down, and eventually I broke the ice by breaking out a bunch of blow. [laughs] We talked for about five hours and we almost missed his reading up at Columbia.

BOLLEN: Oh my God. Was this pre-sobriety Carver?

McINERNEY: No, he was sober. But he felt that that didn’t count. In fact, I asked him, “Hey, does this count?” [laughs] I never used to tell that story over the years because it seemed a bit much. But I think I can tell it now that it’s been 35 years since I met Ray. I got him up to Columbia late, and he read a story really fast. We corresponded after that, and he suggested I might come up and study with him at Syracuse. He saw that the life I was living in New York wasn’t very conducive to writing. But they had a great lineup for fiction. Tobias Wolff was the other teacher up there.

I THOUGHT BY KILLING THAT CHARACTER OFF, I COULD SORT OF KILL THAT PART OF ME OFF, TOO-THE CERTAIN ASPECT OF MYSELF AS THE BAD-BOY WRITER OF THE ’80S.JAY MCINERNEY

BOLLEN: Do you think their styles influenced your writing?

McINERNEY: Initially, but I think if you’re any good at all, you have to eventually shake free those early influences. And I’m not sure that a lot of people reading Bright Lights, Big City would say, “Hey, this is just like Raymond Carver.”

BOLLEN: Certainly not in subject matter.

McINERNEY: But on the other hand, I do think I learned a certain type of economy and a sense of precision that has stayed with me. He would just go through stories line by line and make me question my word choices. It was a great apprenticeship. He never really had some big, overarching theory. It was very much about the specifics of language and pace and storytelling. As a professor, he was much more of an intuitive critic than an intellectual one. Like, he taught this course called Form and Theory of the Short Story. And some irritated PhD guy finally asked, “Where is the form and where is the theory in this class?” Carver was smoking away at his desk and he said, “Well, uh, I guess we read the short stories and we form our own theory about ’em.” [laughs]

BOLLEN: Do you think Lish really was responsible for Carver’s style and success?

McINERNEY: This is a very complicated issue. Over time, Lish became more aggressive in his editing. His edit of Ray’s first book of stories, Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? was not as aggressive as it was in his third book of stories, What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. That’s incredibly pared-down, sparse stories. Lish was cutting whole paragraphs by that point. And Carver was unhappy about it. I was around to witness that strife and read a draft of a letter Ray sent Gordon, saying, “You’ve got to stop this.” I think Lish really helped Carver, and eventually he tried too hard to impose his own sensibility on Carver’s. Early on, it worked for Ray. And the more confident Ray got, the more confident Gordon got, and there was a clash. It’s a very knotty problem because, when you compare Carver’s version of the stories to the final version, the editing is very radical.

BOLLEN: And just with the young writer Jack in your novel, you can’t blame him for wanting the voice and style to be his own.

McINERNEY: Ray’s later stories, after Lish, are much less mannered than the earlier stuff. Ray hated the label minimalism, which he thought was dismissive. Once in a while, I get called a minimalist just because of my connection with Carver. That’s lazy journalism.

BOLLEN: You’re more connected to what could be termed “the ’80s writers,” to Bret Easton Ellis and Tama Janowitz. I’m curious if you ever felt there was a shared aesthetic or sensibility among you? Did you ever feel you were touching on the same material? Or was the lumping together merely due to the fact that you all frequented the same bars and clubs?

McINERNEY: Stylistically, we were very different. It was just that we were young people writing urban novels, with drugs and rock ‘n’ roll in them, which was very new. It was easier to see the similarities than it was to see the differences for the average journalist. But from my point of view, the stylistic differences were huge. It certainly wasn’t as if those guys influenced me, because they came later.

BOLLEN: But you never went to each other for advice or as honest first readers or that type of thing?

McINERNEY: Well, Bret started borrowing my characters. [laughs]

BOLLEN: Story of My Life‘s Alison Poole. How did you feel about that?

McINERNEY: I found it a little weird, but then in the end, I thought it was amusing. When he first told me, I thought he was kidding. And I think it was partly his joke on the idea of, if you say we’re so similar, then I’m going to just act like we’re interchangeable. I also think he really liked that character.

BOLLEN: I like that it reflects this sense that from the outside, New York seems infinite and sprawling. But from the inside, you do end up running into the same 50 people over and over again. A certain cross section of New York is very small. So of course Alison Poole would end up appearing in a few different lives.

McINERNEY: I did write a short story about her about seven or eight years ago. It was called “Penelope on the Pond.” So I have revisited her myself.

BOLLEN: As a reader, I’ve never really been loyal when it comes to any particular publishing house. However, in my early teens growing up in Ohio, I gravitated to those Vintage Contemporaries paperbacks of the ’80s and early ’90s with their bright graphic covers and colorful, spaced-out, shadow-capped titles. The graphic design really made the novels feel au courant. The Vintage Bright Lights, Big City famously had the Odeon on the front; your follow-up, Ransom, had a luminous crane. And then it felt like there were lots of novels coming out by young New Yorkers—I remember the Vintage cover for Jill Eisenstadt’s From Rockaway.

McINERNEY: After the success first of Bright Lights, Big City and then Less Than Zero, suddenly publishers were clamoring for this kind of stuff. So publishers were looking for these urban novels, and I also think a lot of young people who might not have written a novel did write one. Which is all to the good. But some of them didn’t go the distance. There is some frightening statistic about how few people publish second novels—it’s a problem that is not unique to that period. But it’s a quite depressing percentage that don’t publish a second novel. Some people disappear, others change. I remember David Leavitt was sometimes lumped in with us, and he’s still writing. His career certainly took a different turn than mine. But this whole idea that there was a movement is largely spurious.

BOLLEN: Created by the media.

McINERNEY: But it’s true we were hanging around New York together to some extent. I was close to Bret for years. We used to have dinner on Friday nights when I was in town.

BOLLEN: Where were you living during this period?

McINERNEY: Downtown in the Village. I lived in the East and the West Village when I lived in the city. A lot of that time I was living near Sheridan Square in the West Village. But when I started Bright Lights, I was on East Fifth Street over by Second Avenue. That was for the summer. In the winters I was still upstate at Syracuse studying.

BOLLEN: How long did it take you to write Bright Lights, Big City?

McINERNEY: Six weeks.

BOLLEN: What? I thought that was an urban myth. [McInerney laughs] I never believe those stories. Like a novel by definition must take at minimum one year.

McINERNEY: I revised it somewhat. The Paris Review published what would become the first chapter in the winter of ’82. So that means I wrote the first draft in six weeks in the summer of ’83.

BOLLEN: Did anyone have a sense that Bright Lights, Big City would be such a hit? Obviously, The Paris Review—

McINERNEY: But The Paris Review was read by about 4,000 people at that time. It’s not exactly a predictor of commercial success. And most first novels disappeared without a trace. Particularly at that time, there really hadn’t been a big crossover book in quite a while. There was The World According to Garp in the late ’70s. But there was no reason to think this would be one. I was just kind of hoping I’d get a teaching job or something. Random House only published 5,000 copies in paperback. If they had expected anything big, they would have published more. And back then, it took, like, six weeks to reprint a book. When Bright Lights suddenly caught on, largely through word-of-mouth, it sold out, and there were no copies in bookstores for about two months. That could have killed the book. But I think it probably ended up helping it, because people were talking about it and they couldn’t find it. So it became kind of a cult. And then people started writing about it. The New York Times took forever to review it. And when they did review it, it was almost irrelevant. It’s kind of hard to say how that book became so successful.

BOLLEN: Years ago you told me something that has stuck in my head ever since. You said that, back then, long before the Internet, fiction still doubled as journalism. It gave the reader access to worlds they had no other way of breaching. For instance, in the ’80s, most people didn’t have the opportunity to be at a nightclub in downtown New York at six in the morning. Today, you can just check your phone for pictures from last night. But back then, fiction provided that glimpse into the ether.

McINERNEY: Also there weren’t many publications writing about that stuff. So there was no news from certain corners of the world.

BOLLEN: Notes from the underground, which is what Bright Lights provided. It’s in the first line: “You are not the kind of guy who would be at a place like this at this time of the morning.” And by extension, neither is the reader.

McINERNEY: Yeah, the whole downtown New York scene was kind of underground. And it was still possible as a novelist to deliver the news, even if it does take a year to publish a novel. The news moved more slowly back then.

I’VE ALWAYS HAD TO DEAL WITH THE SUCCESS OF BRIGHT LIGHTS, AND I THINK IT CREATED A CERTAIN AMOUNT OF CRITICAL HOSTILITY BECAUSE OF THE FEELING THAT IT WAS TOO SUCCESSFUL. AND BECAUSE OF MY LIFE IN NEW YORK.JAY MCINERNEY

BOLLEN: It made me think about the young writer in your new novel, Jack. He writes about rural, white-trash Tennessee and meth addiction. It’s almost like that’s the new frontier or extreme that most people can’t access. Everyone now can go to a club in downtown Manhattan, but they can’t get to these dire, deep-woods meth dens. It’s an exotic world to most readers, so perhaps the same rule applies.

McINERNEY: Yeah, redneck meth heads.

BOLLEN: You’ve mostly stayed in New York in your novels, with a couple of exceptions like Ransom, which was set in Japan.

McINERNEY: I’d been trying to write that book for years. After I lived in Japan from ’77 to ’79, I had this idea of my expatriate novel, but I just didn’t have the tools yet. I finally put it aside after I wrote the short story that appeared in The Paris Review, the second-person short story called “It’s Six A.M. Do You Know Where You Are?” I suddenly thought, “Hey, that was fun to write, and it feels more authentic and original than this Robert Stone/Graham Greene-like novel that I’m trying to write about Japan. It was sort of like having an affair and cheating on my novel in progress. When Bright Lights was finished, I went back to it. Ransom has its fans, but it still seems like the outlier.

BOLLEN: You mentioned earlier the confusion people had between the lifestyle of Jay McInerney and the lifestyle depicted in Bright Lights. Did readers continue to associate you with the characters in your novels—like a Brightness Falls‘s Jay?

McINERNEY: Bright Lights made a really huge splash. That was how people got to know me. And once you have a public persona, it’s very hard for people not to see you in that light as a person. The public persona is a sort of simulacrum. It may or may not have much to do with the actual person. I’ve always had to deal with the success of Bright Lights, and I think it created a certain amount of critical hostility because of the feeling that it was too successful. And because of my life in New York, which became fodder for gossip columns and the like, there was this impression that somehow I was having too much fun and that I wasn’t living a literary life. The flip side was that a lot of people thought, “Wow, this is cool. I want to live like this and write like this.” There were advantages and drawbacks to the success of Bright Lights. But for better or worse, it’s followed me for most of my life.

BOLLEN: Do you feel that people expect you to write exclusively about New York City?

McINERNEY: Yeah, I do. But it’s not a problem because that’s what I want to write about. I write exactly what I want. I’ve never written a book because I thought it would be popular. I have no idea what’s going to be popular.

BOLLEN: Do you ever feel you are writing about a place that’s an endangered species? In many ways, Bright, Precious Days could be seen as a eulogy to the dying New York of old. Corrine herself calls Tribeca “a suburb of Wall Street.”

McINERNEY: That is a debate that goes on in the book. I think my feeling is, where the hell else are you going to go? [laughs] New York is still the center of the known world as far as I can tell. It’s still the center of publishing, finance, advertising, almost everything except the federal government and moviemaking. It’s the only place where many different tribes mix and mingle. They don’t tend to do that in Washington or Los Angeles; they’re all in the same industry. But here, you can go to a dinner party and sit next to a ballet dancer and an investment banker and a movie star across the way and an artist next to him. I don’t know other places really where that happens.

BOLLEN: You did try Nashville for a few years back in the ’90s.

McINERNEY: That was a part-time thing. It was a good story to say I left New York. [Bollen laughs] But I was just going back and forth. Nashville definitely wasn’t it. But the funny thing is that Nashville now has really caught fire. When I went there, it was a nice retreat, but eventually it wasn’t enough for me. I love the South, but if you’re not from the South, it’s a little difficult to live in a place where one of the first things people ask you is what church you go to. That’s not something that you’re likely to be asked in Manhattan.

BOLLEN: No one has ever asked me that here.

McINERNEY: I still love New York. I don’t plan to ever leave here, even though it has changed a lot. It was a lot more dangerous and diverse when I first came here, and it was a lot cheaper. Now all the young, creative people tend to move to Brooklyn. The trouble with Brooklyn, though, is that it’s a diaspora. The whole idea of urban centers is that it’s centralized. In Brooklyn there are like 15 different neighborhoods. When I first moved to Manhattan, everything was in walking distance of Washington Square Park. It was all downtown. It was SoHo and the East Village and the West Village and even Chelsea and Tribeca, which was barely populated; and the Mudd Club and the Odeon. Everybody was very centralized, and that was a wonderful thing. Downtown Manhattan was an extraordinary place to be for many, many years. Because of the gentrification and the real estate boom, it’s less true now.

BOLLEN: And the characters of the new novel are stuck. They’re not poor, but they aren’t titans of industry. They sort of swing between high society and near poverty. It’s the strange in-betweenness of choosing a professional life of culture and altruism.

McINERNEY: They’re not that well off. They can’t afford private school for their kids. I was really eager to explore this whole matter of people who aren’t rich trying to live in Manhattan with children. It’s a struggle for them. And a lot of the book is to some extent about how hard it is. They have their one-bathroom loft and there’s four of them. They want to stay in Manhattan, and they also want their kids have a good education. That’s very hard if you don’t have Wall Street-level money. I like to think of them as being the middle. And there used to be a lot more of the middle in Manhattan than there is now. Now everyone young I meet lives in Brooklyn. And that’s where I’d move if I were young and came to the city today. Fortunately, I’ve been successful enough that I can hang on here. My life is still Manhattan-centered. There are still a lot of the art galleries and theaters and concert halls. And that’s what I do at night. I don’t go to cutting-edge nightclubs anymore.

BOLLEN: All three of the Calloway novels are wrapped around a profound public crisis—Brightness Falls ends with Black Monday, The Good Life begins with 9/11, and Bright, Precious Days inches toward the financial meltdown of 2008.

McINERNEY: When I thought of writing this book, I was looking back on 2008. On the one hand, it was a moment where the world almost fell apart financially. But on the other, there was a countercurrent of hopefulness and optimism, even as everything was falling apart, because Obama was elected. I think for the majority of well-to-do, educated Manhattanites, that was a hopeful thing. We have New York values, as Ted Cruz reminded us. [laughs]

BOLLEN: Russell is feeling the blow of the financial meltdown. Meanwhile, Corrine is in the midst of a heavy affair. The three novels are in many ways the trilogy of a marriage. And the survival of a marriage over the decades, which, let’s face it, is pretty rare in Manhattan. That’s probably another grim statistic. As someone who has been married a few times, did you feel you had special insights on the subject?

McINERNEY: Certainly I wasn’t able to stay in one marriage. That’s why the subject interests me in a way. If I hadn’t been a writer, I probably would have been an editor. And if I had married my college sweetheart and managed to stay married, this is kind of the life I imagine I might be living. So that’s part of what holds the interest for me. It’s the life I didn’t live, but it intrigues me.

BOLLEN: Is there some innate fault in writers that makes marriage and fidelity difficult? Not that staying married forever is some sort of achievement …

McINERNEY: Well, in order to decide to stake your well-being on something as precarious as writing fiction, you have to be a little bit reckless. Or let’s say, you probably don’t have a really conservative temperament. And that may include being a little more reckless or a little more daring in your personal life. [laughs] I think accountants have a higher rate of monogamy than artists do, for whatever reason. I’ve been married four times, so I’m kind of fascinated by the idea of how people negotiate a marriage over many, many years.

BOLLEN: Was there a temptation to blow up Russell and Corrine’s marriage? Nothing says they have to stay married.

McINERNEY: Oh, yeah. I wasn’t really sure when I started the book what I was going to do. But in the end, I decided it’s much easier to blow it up than it is to try to figure out a way where it survives a crisis. Which is true in life, too, I guess. Some readers may be mad that Corrine doesn’t run off with her boyfriend.

BOLLEN: Certain things would have been easier for her if she had. Like no more one-bathroom, four-family-member loft that she can’t afford.

McINERNEY: Money. One of the things that happens to you in middle age and late middle age is that all the choices you made, some of them without really thinking about them, start to harden around you. And one of the choices that Russell and Corrine made was to pursue their passions rather than to pursue financial gain. When you’re in your twenties, the consequences are kind of distant. But when you have children, and you get older, and you realize that you can’t afford to buy a house on the beach, and you’re having trouble getting the money to get your children a really good education, suddenly it calls into question those choices that you made. You say, “How come these people who are no smarter than I am have such an easy life, and I’m struggling to pay the rent?” That’s a lot of what this book is about. There’s the dynamic of the art and love team versus the power and money team. Russell coins those terms almost as a joke, but there is something true in it. There are people who pursue their passion without regard to whether it’s going to lead to financial security or not. And there are other people who are pursuing financial security as their primary motivation. Obviously, Russell and Corrine are the former.

BOLLEN: Thus, it’s hard to stay in Manhattan … Getting back to my first question—and the first pages of this novel—is the romance of the New York novel a thing of the past? Or is it just a romance to begin with, and the New York artist life itself is a fiction?

McINERNEY: I absolutely think that New York continues to inspire people, because every time somebody says that idea is dead, someone comes along and reinvents the whole project. When I published Bright Lights, Big City, I was told that the novel was dead and young people didn’t read. There was a lot of gloom and doom. And they were wrong. One of the people that kept saying the novel is dead was Tom Wolfe. He wrote an essay about how fiction was dead and that journalism was the new thing. He eventually became more famous than he was before by writing a novel called The Bonfire of the Vanities.

BOLLEN: A lot of reviewers compared Brightness Falls with Bonfire of the Vanities, in terms of analyzing a certain New York elite. Was that novel a reference for you?

McINERNEY: Honestly, I think Bright Lights, Big City influenced him to write about Manhattan. He told me once, not long after I published Bright Lights, what a brilliant idea it was. He said, “Nobody’s written a Manhattan novel in years.” I think I might have had some influence on his choice of subject matter. But my point is, when people declare the New York novel dead, it’s always premature, because people keep reinventing it. And the novel in general keeps getting reinvented.

BOLLEN: Is your own writing schedule the same, or does that get reinvented? Do you sit at the same desk or smoke cigarettes when you write?

McINERNEY: No, I stopped smoking a long time ago. I stopped smoking the year after 9/11. When Bloomberg was outlawing smoking in bars, I wrote a vehement editorial in New York magazine saying that it was a terrible idea and bad for our economy after 9/11.

BOLLEN: My favorite short story by you is the one about quitting smoking. It’s called “Smoke,” and it features Russell and Corrine. It’s so good.

McINERNEY: I tried to quit many times. [laughs] But eventually I succeeded. I was philosophically opposed to the smoking ban. But in the end, I think practically speaking Bloomberg probably saved a lot of lives. It’s sort of hard to imagine now, but I used to come to this very restaurant and smoke cigarettes at the table.

BOLLEN: I can remember asking to sit in the smoking section.

McINERNEY: And we all did.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN IS INTERVIEW‘S EDITOR-AT-LARGE.