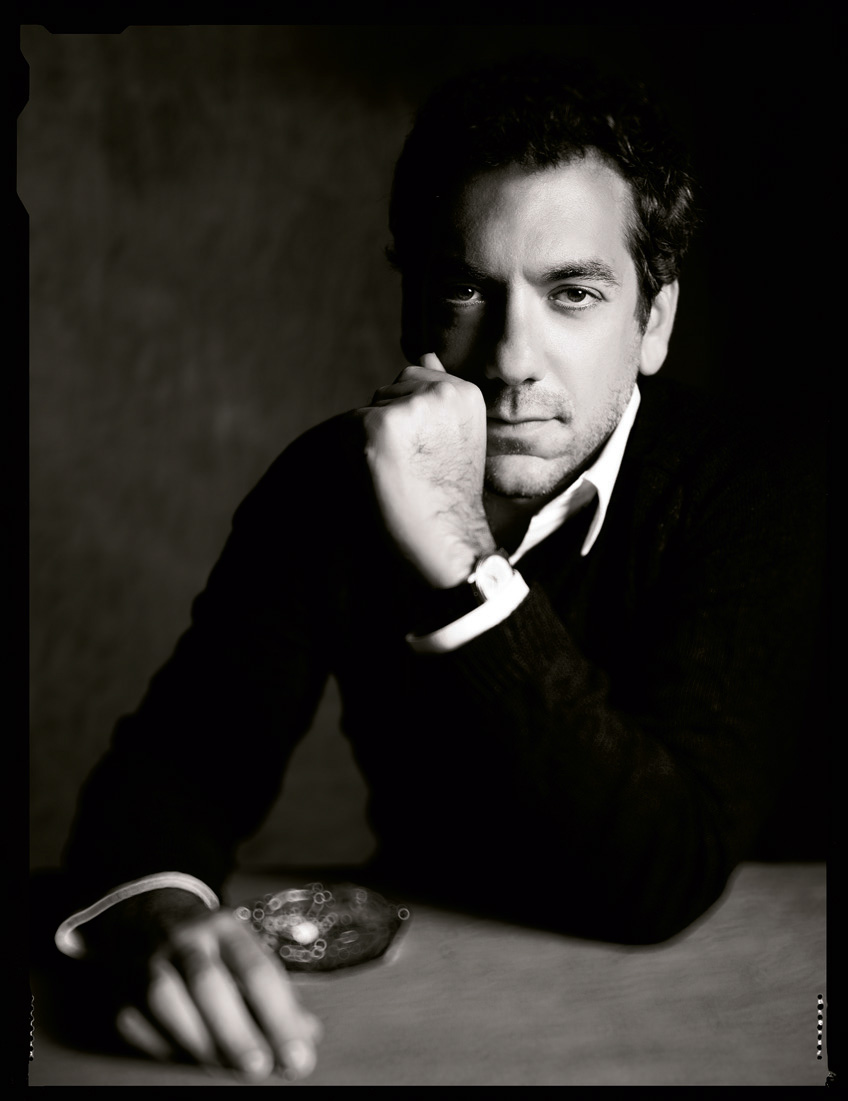

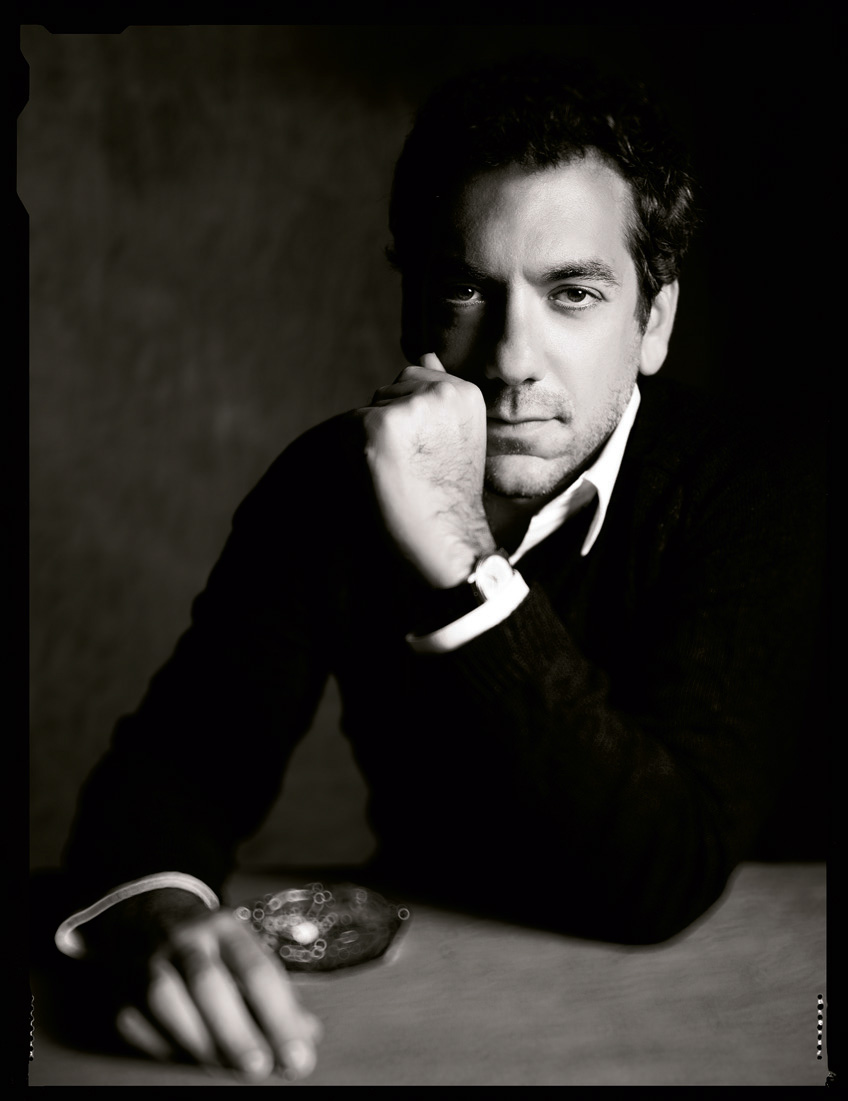

Todd Phillips

IT FEELS LIKE not THAT LONG AGO that I when you’re shooting a movie like the hangover in some back alley in las vegas at two o’clock in the morning, you’re not thinking, i can’t wait to see what the hollywood foreign press thinks about this . . .Todd Phillips

Todd Phillips has directed nine feature films, the majority of which are funny, a handful of which are funnier, and two of which-2003’s Old School and last year’s Golden Globe-winning post-bachelor party epic, The Hangover-are among the funniest that anyone has directed in the first decade of this century. The popular take on the 39-year-old Phillips’s oeuvre is that his movies revolve around the burdens and anxieties of a certain kind of archetypal married, ex officio fraternity pledge master now encumbered by the chains of adulthood (see Vince Vaughn in Old School, Bradley Cooper in The Hangover), and his equally representative well-meaning best friend who accidentally drinks too much and makes bad decisions at parties he’s not allowed to attend (see Will Ferrell in Old School, Ed Helms in The Hangover). But, in actuality, Phillips is a much more complicated-and much more crafty-director than that thumbnail would illustrate. He grew up on Long Island and began his filmmaking career while still an undergrad at NYU with Hated (1994), a documentary about rocker GG Allin, the late-and legendarily antisocial-drug-addled punk extremist who spent his life bouncing in and out of jail and liked to strip naked and smear himself with his own feces during performances. In his next film, another doc called Frat House (1998), Phillips and his filmmaking partner at the time, Andrew Gurland, attempted to delve into the beer- and vomit-stained world of fraternity hazing, which resulted in Gurland being hospitalized and a memorably aggro frat brother named Blossom repeatedly threatening Phillips with physical violence. Frat House won the Grand Jury prize for documentary at the Sundance Film Festival in 1998, however, HBO, who co-produced the project, refused to air it amid allegations that some of the frat brothers featured in the film were asked to sign releases while they were drunk or on drugs and that certain scenes were staged. Nevertheless, the very public controversy surrounding the film opened the door for Phillips to a narrative filmmaking career, which, beginning with Road Trip (2000), has been marked by an informal study of youth and young manhood-and what it means to get older, have responsibilities, make commitments, bond with other men, and even be a man.

Phillips’s latest film, Due Date, which hits theaters this month, is framed by another formative moment in a man’s life-becoming a father-but, in many ways, it’s really about learning how to stop being a son. The film stars Robert Downey Jr. and The Hangover‘s Zach Galifianakis as a pair of strangers who meet at an airport and become unlikely travel-mates when a convoluted set of circumstances forces them to drive together from Atlanta to Los Angeles after they’re both placed on the no-fly list. Downey Jr.’s character is a straight-laced architect who is rushing back to L.A. because his wife is scheduled to give birth to their first child later in the week; Galifianakis plays a fledgling actor named Ethan Tremblay who spends most of the film decked out in tight jeans, jazz shoes, a scarf, and a Lilith Fair T-shirt and is heading for Hollywood in search of stardom.

When we spoke, Phillips was in Bangkok, Thailand, preparing to begin shooting The Hangover 2.

STEPHEN MOOALLEM: I recently went back and watched Frat House, and there’s something that you say very early in the narration that I think is very interesting in light of some of the films you’ve made since. You say that you wanted to make a documentary about frat life because you were “always interested in the lengths that men will go to in order to belong.” That idea is one that seems to run through a lot of your films-along with this tension that comes from the notion of being constantly torn between what you think is expected of you and what you really want.

TODD PHILLIPS: Well, all of my films, forever, have been about guys and their relationships. I mean, I don’t like to get too heady about it, but I grew up raised by my mom and my two sisters, so I never had a real male influence in my life. I never really understood heterosexual male relationships. It’s like, what do you get out of that relationship? I never understood that bonding that happens. It’s something that I’ve always been fascinated with because there’s such an awkwardness to most heterosexual male relationships. You see women who are friends, and they kiss each other good-bye, and they’re just so much warmer with each other. But there’s this thing with guys where, even between best friends, there’s a standoffishness. There’s still this tension to contact. I also think when I said that thing in Frat House, it was partially because of the fact that my mother raised me with the idea that you should always do everything you can to not fit in, to be an individual. I was taught that you didn’t want to be part of the group-that it was better to do your own thing.

MOOALLEM: How did you go from that to making a documentary about GG Allin?

PHILLIPS: I really got into filmmaking through photography. I used to take photos of my friends from high school doing fucked-up things, like taking drugs, doing vandalism. I did this whole series that I submitted to NYU, which was really a kind of photojournalistic document, and that led to the idea of making documentaries. I remember that when I got to NYU, everyone was writing scripts. But I was 18 at the time, and when you write a script, so much of it is about what you pull from life, and this sounds sort of cheesy, but I felt like I didn’t have enough life experience at that point to write a movie. So I saw documentaries as a way to kind of live in fast-forward through the filmmaking process, which led me to make Hated and travel around with GG Allin for a year, which was completely intense and ridiculous.

MOOALLEM: GG Allin is lost in history a little bit now, but for people who don’t know, he was probably one of the most extreme figures to come out of the ’70s and ’80s punk-rock scene. In fact, I’d hesitate to say that he came out of a scene-part of the reason he’s lost in history is that he was so extreme, even the other extreme people never fully embraced him.

PHILLIPS: He was so extreme. There was nothing cute or easy about him. It wasn’t even like Marilyn Manson, where it felt gimmicky. GG was truly a schizophrenic, bipolar maniac who didn’t give a fuck about anything. I remember taking the train into the city when I was 16 or 17 and seeing GG at the Lismar Lounge, which used to be on First Avenue. To get to the stage, you had to walk past a bar and down a set of stairs. So I walked in and GG was sitting there at the bar shooting heroin, which is something I’d never seen in my life. Eventually he got up and turned around and just tumbled down the stairs and had a violent fit, and that was it. There was no show-that was the show. So when I was looking for documentary subjects at NYU, I thought of him. He was in and out of jail all the time, and at that time he was in prison in Michigan, so I wrote him a letter, and that was how it started. We began this relationship through letters. I was retarded. [laughs] But he was legitimately crazy and not somebody to have a relationship with.

MOOALLEM: So, objectively speaking, who was scarier: GG Allin or Blossom, the frat guy who threatens to kill you in Frat House?

PHILLIPS: [laughs] I’d have to say Blossom. In a very weird way, I could relate to GG on some level, through music, the world of punk rock, and, quote-unquote, art. With Blossom, there was zero connection-it was just all anger, all the time. Just so much fear comes to me with that name. The best part about it is that his name is Blossom.

MOOALLEM: You never really explain that in Frat House-why he’s called Blossom.

PHILLIPS: That was his pledge name when he was rushing the fraternity. The other guys thought he looked and dressed like Joey Lawrence from the TV show Blossom.

MOOALLEM: Not to harp on Frat House, but parts of it are not all that far away from what you see on Jersey Shore. Watching them back-to-back is almost like a study in the cumulative effects of more than a decade of reality television on the general populace.

PHILLIPS: When we did Frat House, the power of the camera was still not fully understood by regular civilians. There wasn’t that innate understanding of the impact of reality television, where they’d be like, “Wait a minute. This guy holding the camera and this guy in the corner holding the microphone: they could change my life-and not necessarily in a good way.” Reality television hasn’t killed documentaries, because there are so many great documentaries still being made, but it certainly has changed the landscape. There is this breed of gimmicky documentary that is basically a reality show. You know, “I’m gonna eat nothing but McDonald’s for 30 days”-that’s kind of a television-show concept. But I think the form has changed so much because it’s very difficult to just be a fly on the wall anymore. Everyone understands the power of the camera now, so when the Jersey Shore crew is out there filming Ronnie-who I love-he is, in a sense, performing. But if I think back to when we made Frat House in 1997, that awareness just hadn’t permeated fully.

MOOALLEM: So many of the problems that HBO had with Frat House seem almost quaint in comparison to what goes on now. A lot of what was offered as critique back then-rightly or wrongly-is now sort of built into the mechanics.

PHILLIPS: How else are you supposed to make this shit? Of course, you get kids to sign releases when they’re drunk. They’re gonna sign one when they’re drunk. When they’re not drunk, they’re gonna fax it to their dads-and, you know, that’s a whole other issue. But we thought we got around it. I thought it was brilliant-I thought we were being geniuses. Then I found out it was illegal.

MOOALLEM: You kind of stumbled onto something that everyone else discovered later on.

PHILLIPS: Yeah. I was a pioneer. [laughs]

MOOALLEM: Let’s talk about Due Date. How did this one come together?

PHILLIPS: I make decisions to do movies based on the cast. I’d just been working with Zach [Galifianakis] on The Hangover, and I was thinking, I’ve got to find something to do with this guy immediately. As a director, you’ve always got five or six scripts in development. So with Due Date it was like, “This would be great for Zach.” And then I said to myself, “If I can get Robert Downey Jr. in the other role . . .” Because Downey is probably one of the greatest actors alive, and just thinking about the kind of clashing styles that he and Zach have got my mind going-I mean, they couldn’t be more different guys. So it was much less about the road trip in my mind than the coming together of these two giant personalities.

MOOALLEM: Had Robert and Zach met before?

PHILLIPS: Well, I’d met Robert a few times. I knew that he’d seen The Hangover-he’d gone to a screening, but the movie hadn’t even come out yet. I’d sent him the script for Due Date, and he was interested, so we arranged for Zach and I to go over to his house for dinner, which was a nightmare experience. We were going over to Robert’s house-he was living up in this canyon in the Palisades at the time-and for whatever reason, Zach decided to ride his bike there from Venice. Now, Zach is not Lance Armstrong. He turns up 30 minutes late, covered in sweat, and kind of barrels into Robert’s house. So we sit down, and one of the first remarks Zach makes is about a woman who is a famous personality. It was a very funny, ridiculous joke, but he didn’t realize Robert had dated this woman in the past, and Robert said, “Well, you know, I used to date her.” I was like, “This has not started well.” [both laugh] But it is intimidating to be around Robert on every level-in a very good way. He’s just very challenging, and I think that’s why he’s such a good actor.

MOOALLEM: You’ve always been good with casting. A lot of people forget that before Old School, Vince Vaughn was doing sort of darker movies like Domestic Disturbance (2001), and your movie opened up this entire other career for him. There was a similar sort of new understanding to what Bradley Cooper and Zach were capable of after The Hangover.

PHILLIPS: With Vince-and he would confirm this–it was a fight to even get him in Old School. Dreamworks didn’t understand–“You’re making a comedy with this guy who does movies like Domestic Disturbance and Clay Pigeons [1998]?” I knew, though, just how naturally funny he is. Vince just looked so good in Old School in a very different way than he did in Swingers [1997]-he’s a little bit lived in–which is why I think he brings so much to that movie. Bradley Cooper is another guy like that. I love confidence in a guy. I don’t have it, but there’s nothing sexier, and Bradley just projects such a tremendous amount of it on screen. He’s not like that as a person, but there’s this swagger that he seems to have that I think was important for his character in The Hangover, so we kind of built it around that. Zach is an example of someone who doesn’t have swagger. But he does have this sweetness in his eyes that you just can’t act–I’ve worked with a lot of funny people, but the only other guy I can think of who has that quality is Will Ferrell. It’s this sweetness that allows them to get away with a lot. Funnily enough, Zach came in and read for a part in Road Trip. So I’ve known him now for more than a decade. He’d obviously been in movies before The Hangover, but he’d be the first to tell you that he was never really used right. It was like no matter what he did, he would somehow always seem to disappear into the background. So when we were talking about The Hangover, I kept saying to him, “You know, if you do this part, you really need to take center stage. You can’t disappear.” But he’s so not that person. I just feel like he needed a part that kind of showcased what he could do in the correct way and really captured his sensibility. Now it seems like he could be unstoppable. But it’s always interesting to watch the choices that people make after something like that happens-particularly as a director. It’s just interesting to watch careers.

MOOALLEM: The idea of The Hangover 2 taking place in Thailand . . . I’m sure it will get people’s imaginations wandering. Is there anything you want to say about it?

PHILLIPS: Well, it’s funny, because when you do a sequel, people always have this assumption of, “Oh, they’re doing this because everybody just wants to make money.” But the truth is, we had the greatest time making The Hangover, and, while, yes, those guys are going to get paid more this time around, we’re doing it because we truly want to make a movie that lives up to the first one. I understand what The Hangover means to people-people love that movie. So I’m not delusional. I know what people think and expect. I mean, we won a Golden Globe for The Hangover. I would never have expected that. I’m not saying that I didn’t want it, but it’s not something that’s in your mind. When you’re shooting a movie like The Hangover in some back alley in Las Vegas at two o’clock in the morning, you’re not thinking, Well, I can’t wait to see what the Hollywood Foreign Press thinks about this . . .” [both laugh] But I think we wrote a really funny script for Hangover 2, and it’s got a structure to it where we can keep the surprises at a maximum. And then there’s Bangkok . . .

MOOALLEM: So what kind of trouble can you get into in Thailand?

PHILLIPS: Oh, my god-it’s crazy. It’s just packed with people. It’s so hot here right now-Plus, it’s weird. You know how sometimes you go somewhere and you feel like, “Okay, this is where I’m supposed to be”? I kind of felt like that when I was living in Caesars Palace for three months while we were shooting The Hangover. I’d go downstairs for a cigarette at midnight after a long day of shooting and wind up sitting in my pajamas at a blackjack table and gambling until 3 o’clock in the morning. All that time I just had the sense of, “Oh, I belong here. This is where I belong.” Then I came to Bangkok and everything shifted. It’s like The Matrix-everything just shifted. If I don’t come home in a body bag after Hangover 2, I’ll be unstoppable. We’re going to be here for three months and that should be the end of me. I don’t think I’ll ever die if I don’t die here.

Stephen Mooallem is the Editor in Chief of Interview.

Grooming products: Chanel, including Purete Ideale T-mat Shine Control. Styling: Patrick Mackie. Hair: Andre Gunn/The Wall Group. Makeup: Benjamin Puckey/See Management. Set Design: Jeff Everett. Special Thanks: Pier 59 Studios.

Todd Phillips

Â

Todd Phillips, second from right, and the cast of The Hangover

Â

Bro-comedy maestro Todd Phillips (Old School, Road Trip) has made plenty of films about men being boys. In The Hangover, a trio of bachelor-party survivors played by Bradley Cooper, Ed Helms, and Zack Galifianakis try to piece together what happened during a disastrous night in Las Vegas. (Hint: it involved some spontaneous dentistry and a chicken.)

Denying widespread rumors that a sequel is in the works, Philips (who also co-wrote Borat) sat down with Interview to explain why women loves his movies and why Vegas is a risky place to put up a film crew.

Darrell Hartman: Everyone’s been reporting that you’ve already got a sequel in the works. True?

Todd Phillips:Â Ah, no. These rumors start on this thing called the Internet. Apparently, some fat kid in Tampa can just write something and it becomes true. Warner Brothers, I think, would be into doing it if the movie works financially. But there’s not a greenlit sequel.

DH: Did you always envision this as a Vegas movie?

TP: The Hangover sounds really clichéd on paper. “It’s a bachelor-party movie.” But really, it’s not that-you never see the bachelor party. It’s really about the fallout of bad decisions, and nowhere do you make more bad decisions than in Las Vegas. I think they should change their slogan: “Every minute, another bad decision is being made here.”

DH: And this is about a bunch of guys who make a whole bunch in a single night-but can’t remember any of them.

TP: Yeah, I describe it as Memento for retarded guys.

DH: The Bourne Identity with morons.

TP: Right! Stillborn Identity. Let’s see who else we can offend.

DH: In some ways, this is as much a detective story as a comedy.

TP: That was the appealing part. Doing a bachelor-party movie didn’t necessary feel like super growth for me, but the structure and the storytelling were exciting-that mystery element, people trying solve it. There’s always these slow moments in comedies where you lose the audience. And in this film we don’t, because they’re actually genuinely interested: “How did that baby get there?”

DH: And you wait until the closing credits to show what happened that night.

TP: I think that’s one of the great parts of the movie-the third act happens during the credit roll. Comedies don’t generally have very satisfying third acts. They don’t have endings-they just stop. And I go on record as saying this might be the most satisfying, craziest credits sequence in a comedy. I defy one person to name the second [assistant director].

DH: The old-fashioned definition of comedy is a story that ends with a marriage. But here, and in Old School, you seem to prefer stories that begin with one.

TP: Yeahâ??it’s where you start to unravel, when you get married and realize, “What have I done?” Marriage is a traumatic time for guysâ??and girls too. It really represents that moment in life where you’re choosing between responsibility and irresponsibility.

DH: Are you married?

TP: I’m not. But I have been engaged. I don’t have a fear of marriage; I just think it represents a really unhinged time in people’s lives. Awkwardness is great to mine for comedy-awkwardness and pressures.

DH: How was it shooting in Vegas?

TP: I actually thought it was going to be more difficult than it was. Bur Las Vegas is a gateway city. It’s full of temptation. “Some people can’t handle Vegas”-that’s the tagline of the movie. It came from the tagline of our crew.

DH: How do you mean?

TP: I think people can live in Vegas and have functional lives, but when you’re there in a hotel casino, living on the strip, the options on the off-days are pretty rough-especially for the crew guys. It’s very expensive to go to the spa at Caesar’s. It’s less expensive to play video poker and chase whores. So we literally had wives showing up, taking their husbands and putting them in rehab. And you’d be going, “Hey, where’d that driver go, so-and-so?” “Uh…he’s, uh…we got a new guy.”

DH: There’s a pivotal scene that involves card-counting. Did that make your hosts uneasy?

TP: No, no, no. They shot a whole movie, 21, about that. Vegas welcomes you to try and count cards.

DH: I guess for every person who succeeds…

TP: There’s 500,000 guys who drop their entire Christmas bonus attempting to pull it off. You need to have a mind to do it. I mean, know what it is, but I smoke way too much pot to keep track of three cards, let alone six decks.

DH: Who were your comedic influences?

TP: I like to pretend I grew up on Billy Wilder and Preston Sturges, but the truth is I grew up watching The Jerk and Stripes and Blues Brothers. And I think this movie harkens [back] to those movies: it’s guys on a mission. At the core, there’s love between the guys. They give each other a hard time, but you know they’re real friends. I think Judd Apatow does that really well-sometimes overly sentimental for my taste, but when you watch his movies, you know they love each other.

DH: It’s not as convincing when a movie shows friends being friendly.

TP: Right. You’re never nice to your friends. You’re nice to people you don’t like!

DH: The Zach Galifianakis character is kind of in his own world. What was it like working with him?

TP: No one does left-footed better than Zack. I think he’s the funniest guy out there right now-like, Andy Kaufman-esque brilliance. I’d been following his stand-up in LA for years and I always thought, “God, I’d love to find a role for this guy.” But his act is so not-translatable. He’s not up there telling jokes. It’s like performance art. He’s had bit parts in certain movies, but he tends to disappear because his stuff is so subtle.

DH: Whose idea was it to put him in a jock strap?

TP: That was Zack. And of course he always regrets it. He loves to say, “I gotta learn not to suggest things, because Todd will do anything.” Like masturbating the baby. We had a doll that would stand in for the baby… and so I’m just talking to the cinematographer and all of a sudden Zack goes, “Hey Todd, check it out.” And I look over and he’s got the doll’s baby hand and he’s pretending the doll’s masturbating. So I laugh for 5 minutes, because I’m 14 years old. Then I go, “We’re putting that in the movie.” And he goes, “No, I’m not doing that in a movie! It might not even be legal!” I go, “I’ll deal with the parents.”

DH: What’s taboo in comedy now?

TP: I’d be the wrong person to ask. You never rein it in on the set; you always do everything. You’re basically documenting mayhem. There’s only certain crew people that can handle that sort of, “Oh, we changed it, we’re not doing that anymore, we’re gonna jerk the baby off.” And then in the editing room you kind of figure it out. For me, if it’s funny, it’s not really offensive.

DH: And you don’t worry about alienating the female audience?

TP: Women love this movie as much as guys, which confounds me. One of the reviewers told me women loved Old School. She said, “You’re pulling back a curtain on a uniquely male event, fraternities.” And I think The Hangover is the same thing, this ritual male behavior. Women have never really been invited to that.

DH: And in both, you confirm their worst fears.

TP: That’s right.

Â