film

The Directors of The Stroll on Jerry Springer and Documenting Sex Work

The Emmy-nominated artist and producer Zackary Drucker’s impactful role as a consultant on Transparent brought the trans narrative to the forefront, as she seamlessly integrated the community into the production process. And Kristen Lovell began her journey as a filmmaker after appearing in Queer Streets, a 2007 film that follows trans youth living in New York City, and in which Lovell’s gritty New York accent and Holly Golightly mannerisms shined brightly.

Last year, these women came together to direct The Stroll, a gripping film that celebrates the vibrancy trans people brought to the Meatpacking District before its gentrification, with a focus on the neighborhood’s cultural debt to trans sex workers in particular. From the 80s through the aughts, The Meatpacking District was the dark and musty epicenter of transgender sex workers, a film noir-esque adult playground scented by entrails and decaying meat carcasses. The odious smell was the lambs’ blood that kept gentrification passing over “The Stroll,” a safe haven for trans and gender-queer folks, and a place where they could have jobs in a world where they, much like the district, were seen as a blight. Imagine just having cried your lashes off into a puddle. Tears of validation, utter loss, and even joy, the joy of learning you have history. This was my experience watching The Stroll. And shortly after the film debuted on MAX, I had the pleasure of speaking with to Drucker and Lovell, one of my trans roots. Although I was a little shook, asking big questions about my little feelings, we had an affirming conversation about their film, their lives and inspirations, mothers and sisters, and more.

———

ZARINA CROCKETT: I’m super excited to be having this conversation with you both. How is everybody today?

KRISTEN LOVELL: Great.

ZACKARY DRUCKER: Loving every moment so far.

CROCKETT: Let’s get into it. Kristen, tell me what sex work was like in the early 2000s, pre-internet.

LOVELL: By the early 2000’s, sex work in New York City got increasingly harder to do without being penalized. At first it was a slap on the wrist and community service, but by that time Vice Squad was snatching us up or ambushing us on dating sites. And the sentences were getting harsher. You would do 30 or 90 days, come out, get snatched again, and you’re back in for another 30 to 90 days. It became exhausting, going in and out of the prison industrial complex system. Then when 9/11 happened, it seemed like the stroll [on West 14th Street] just came to a halt. The rumor was that a lot of the clients died in the World Trade Center and that’s why there wasn’t enough money, but I don’t think that was true. I think it was because of the cleanup that was happening when the police convened in the area and started to shut stuff down. That impeded the traffic coming in because the stroll was technically from 43rd street all the way down to the [Twin] Towers. Before, we would get the dates in the Meatpacking District and take them down to Tribeca and the World Trade Center. We didn’t have access to those spaces so during that time we had to rely heavily on walk-in clients—you would see all the New Jersey plates circling the block—and eventually the computer.

DRUCKER: Wonderful summary, girl.

CROCKETT: I can tell you were so entrenched in this trans history, I’ve learned so much. You got your start working with Queer Streets, which is one of my transsexual roots. Your presence in Queer Streets actually shaped the woman I am today. So how did you get into filmmaking?

LOVELL: Me and JD go way back to the days of FIERCE [Fabulous Independent Educated Radical for Community Empowerment] and Fenced Out, which is another documentary that we were involved with. Around 2010, we wanted to present a workshop about media representation at the Trans Health Conference. I didn’t want to do a PowerPoint presentation, because everybody was doing PowerPoints then. I wanted to do something visually gripping that would incite emotion and action. JD gave me this DV [digital video] camera. I went and I recorded some girls’ ideas on how media was representing us at the time. One of them was on the Jerry Springer show. And we put it on YouTube and I presented it at the Trans Health Conference. I thought there was going to be a tiny room and only four people, but they gave me the biggest room in the venue and it was packed. After that, I did a photograph series called Becoming Visible with Samantha Box, following us during the stroll. It’s important to document and share this history. We would get a lot of young people that would come into Sylvia’s Place and they had no clue who Sylvia Rivera was or what it took to have the shelter that we had there.

CROCKETT: I cried during the scenes with all the history and now I’m getting so much more history, so thank you. Zackary, we watched Kristen start her journey into womanhood in The Stroll. What was it like for you to discover your womanhood?

DRUCKER: The first trans woman I ever recall seeing was a Black trans woman who was a sex worker on the streets of Syracuse, New York where I grew up. It wasn’t until I moved to New York City in 2001 that I started to meet trans people. I met one of my first trans sisters two weeks after landing in Brooklyn. I was 18 years old and I had been a queer youth activist in Syracuse because I was one of those kids who was always out, always visibly queer. I remember flyering for FIERCE and going to one of the meetings, and Kristen is one of the founders so it’s likely that we overlapped 22 years ago. I was in a relationship with somebody who worked at Harvey Milk [High] School, so I started taking hormones through the HOTT [Health Outreach To Teens] program at Callen-Lorde. So my formative years were in New York City.

CROCKETT: That’s amazing.

DRUCKER: Definitely. One night when I was 18 years old I was at a bar in Williamsburg where I knew I could drink with my fake ID. I was taking the R train home late at night and this woman got on the train. She was comforting another woman and I will never forget the way that she channeled energy into me as I was sitting there and acknowledged me before she got off the train. And I realized a few years later that it was Sylvia Rivera and that she was recognizing me as a person of shared experience with her.

CROCKETT: That’s beautiful. I love hearing stories about how trans women came into their identity before the internet was around, because as we know, Jerry Springer was the check for trans girls.

LOVELL: I mean, I have gone to Jerry and I’ve gotten my beads.

CROCKETT: Honestly, I probably saw your episode. Tell me about Jerry.

LOVELL: On the Maury Show, I would see those episodes of, “Is it a man or is it a woman?” They were trying to spook the girls and I was tired of that shit. So maybe 10 years ago we get to the Jerry Springer show and I’m like, “If they start that crazy shit, we’re going to turn up.” Jerry Springer comes out, he sees me, and he’s like, “Oh shit,” because I’ve been kind of bothering him on the internet. So I’m in the audience and I stood up like, “Jerry, I just want you to give me my beads.” And I lifted my shirt and flashed my titties and snatched my beads. And then my girlfriend did the same thing. It was like, “Whatever, they’re going to see some trans titties today.”

CROCKETT: That is a lesson in controlling the narrative. Okay, who cried the most while filming The Stroll?

DRUCKER: I feel like I did. But what do you say, Kristen?

LOVELL: There were definitely times where I felt the emotion of being back in that space. I used to be on these corners not too long ago and now here I am filming a project for HBO. I have done a lot of crying and processing this full circle moment of becoming the filmmaker that I wanted to be. During the pandemic, I wasn’t as active with activism, but then I realized that this film is an act of revolution in itself. I get messages all day from people who’ve seen the film from all over the world, it’s a beautiful thing.

CROCKETT: This might be a little heavy, but I wanted to get to the meat of your project because it’s so powerful. What was the hardest thing to film?

DRUCKER: For me, it was witnessing Izzy have a breakdown on 14th Street. Izzy was a real canary in the coal mine, the person who just let it flow. As a witness, that was a tough moment. What was it for you, Kristen?

LOVELL: Things that weren’t put in the film, like when we went to that guy’s house and he had very racist and transphobic artwork in his home. Every time I tried to ask him questions, he would totally avoid the question. Every piece of artwork that he presented to me that was supposed to be a Black trans woman was racist. What really set it off for me was when he showed me the artwork of the witch and it just so happened to be a Black pre-op trans woman. I lost it on the inside, but I had to keep my composure. Eventually he didn’t want to participate in the film, but that was one of the hardest moments for me to see.

CROCKETT: Thank you both for sharing those things. Let’s let go of all of that. My favorite thing about the doc were the little cut scenes. What was the motivation behind that?

LOVELL: We were doing these collages with the animation team, trying to immerse people into this world via these photographs. We left both versions of the animation in, which I love. Zackary found some actresses and directed in Los Angeles and me and Sean and Liz were here in New York with Tabitha. So we did it bicoastal. It was amazing.

DRUCKER: It’s the most fun to create with new collaborators, especially when you’re deep in an edit and you’re so lost in the weeds. Awesome + Modest is an incredible team of animators and they always take it to the next level. We started with the superhero because we always knew that was going to be in the film. Buffy, Battle Bots, Wonder Woman. That’s kind of where it started, and that kind of unlocked the rest of the superhero segment.

CROCKETT: One line I will never forget is, “When one of us is in trouble, we’re all in trouble.” As a younger trans woman, I feel like our communities are disconnected and we just don’t have the same homogeny. What was the community like during that time compared to now?

LOVELL: Back in the day when I would go to rallies and protests for trans-related issues, there was never enough girls out there to represent, and you wouldn’t see the broader community. Ostracization, relationships, outing themselves— at the time these were reasons why the girls weren’t standing up. We were scattered about. Unless you were in the ballroom scene and you were traveling, we didn’t have that connection until social media. And then, boom. It’s like the girls in The Stroll. We left the stroll but we all maintained communication and contact through social media. We’re more mobilized now than we have ever been in our entire history. I wasn’t at the Brooklyn [Liberation for Trans Lives] march, but when that footage came my way for the film, I was like, “Oh my god.” I don’t think I had ever seen a rally like this where everybody is out there saying Black trans lives matter. And for Ceyenne [Doroshow] to get on that podium and speak in that manner was powerful. This is beyond the tipping point. We are making our marks and fighting for the things that we know we’ve long deserved. To be a trans person alive today, this is a very special time.

CROCKETT: That put so many things in perspective for me. Zackary, I would love to hear your take on it.

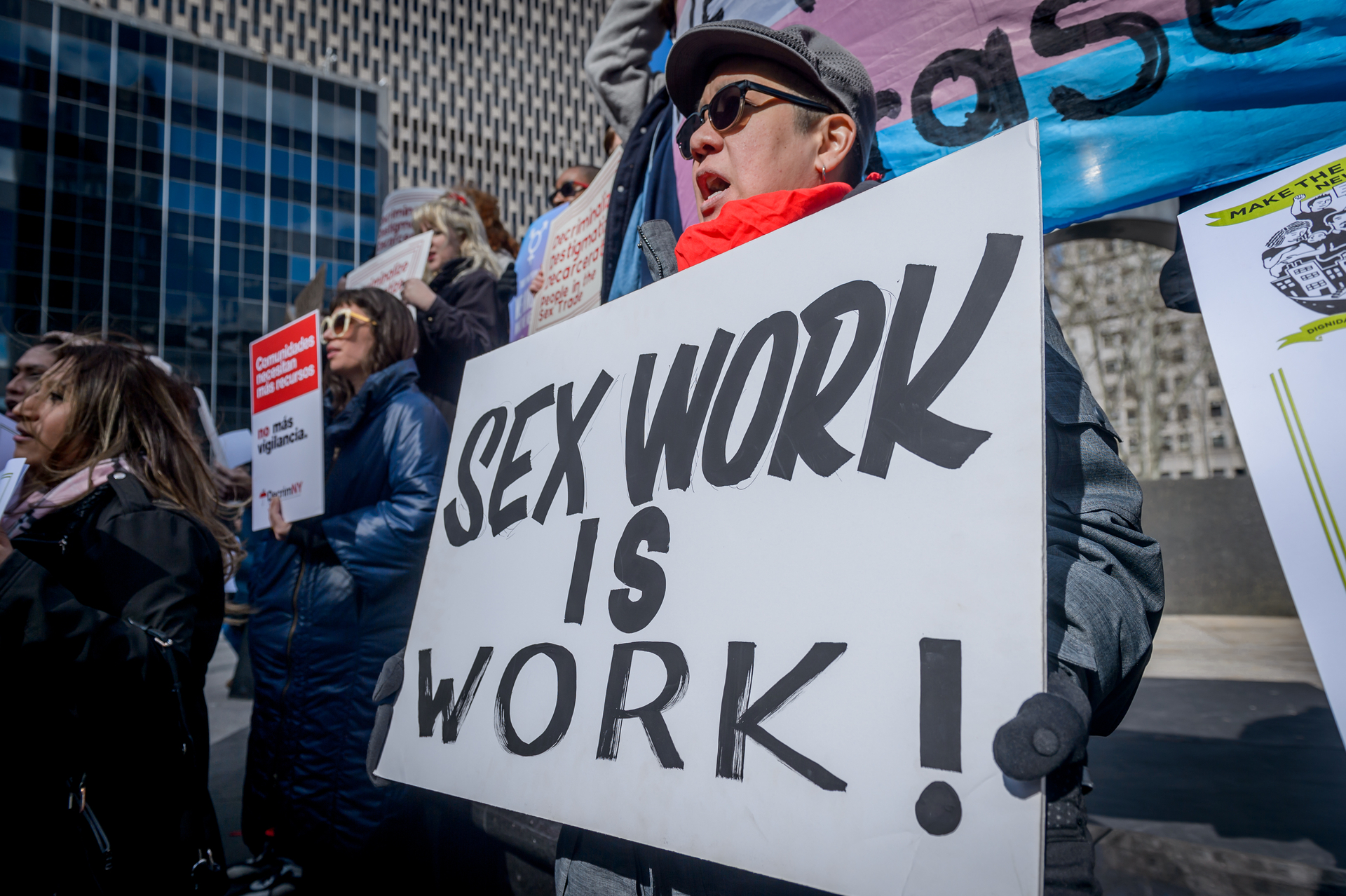

DRUCKER: I feel buoyed by the sisterhood, by being conscious of our predecessors and the people who have yet to come into this world, because we will be born into this world no matter who tries to legislate against us. I often think of my grandmother, Flawless Sabrina, who described the ’50s through the ’80s as an anti-community. There were always strolls around the world since the earliest civilizations, and it’s crucial that we affirm sex workers and we fully decriminalize sex work. Sex work is work and sex workers deserve all the protections of the law as self-employed entrepreneurs. This is a future that we move into without fear, knowing that totalitarian forces are always trying to crush us no matter what. Trans people have been sex workers forever. Trans people have survived in underground economies. So if anything, the stroll is probably the first community of trans folks. I mean, by the 1960s people started to come to a Stonewall Bar or to a Jewel Box in Kansas City or a Cooper Do-nuts in Los Angeles. But before them, trans people were in the streets, surviving. And that is a through line to today. Things are better and worse simultaneously because progress moves alongside opposition. We are in the spotlight because it is our time. We offer an alchemy, a magic alternative to white heteronormative patriarchy, which is very boring. People are bored and people are threatened by our joy. It’s a crucial time to come together. It’s so important that we are present in community with each other in deep ways. Greet each other on the street, acknowledge people. Human kindness is the silver lining, in the most dire circumstances until the end.

CROCKETT: Thank you so much. Both of you had so much wisdom for that question. What’s next for The Stroll?

DRUCKER: Kristen’s follow-up movie.

LOVELL: There’s still more to that story that we can get into with a follow-up.

DRUCKER: And so many unsolved mysteries that we didn’t even get to in The Stroll.

CROCKETT: My last question, who inspires your trans womanhood? And what would be your advice to a future trans woman in film?

LOVELL: It’s all the girls that I stood at a corner with that are no longer here. They were the ones I looked up to. They let me know when to hide and duck and gave me the daily briefs. For filmmakers, never give up. If you have a dream, just keep pursuing it. You’ll figure it out. It’s like a puzzle. If you know that you have ideas and they’re good, you can make it.

DRUCKER: The cast of The Stroll, the women who shared their stories with us. Kristen, you’re a huge inspiration to me. Working on this was just the honor of a lifetime. Ceyenne Doroshow, who I met as a young person. Her mother, Flawless Sabrina, Jack Doroshow, my grandmother. To young people, people are always saying these are unprecedented times, but we are unprecedented people. It takes all of us doing this groundwork side by side to push this thing forward. I love what Nicole says in the film that we owe it to every trans woman before us and everyone that comes after us, and we keep pushing. That is the game of staying alive as long as we can and as true to ourselves as we can be.

CROCKETT: Thank you so much for the wonderful work that you women created. You created a piece of history by capturing history and you’re inspiring people for generations to come. How does it feel to be the Wonder Women? Because you are the heroes in my life. That’s all for me.

DRUCKER: You’re a gift.

LOVELL: I need to follow you on Instagram.

CROCKETT: I just followed you on Instagram. I didn’t want you to know who I was until the interview.

LOVELL: I’m going to check now.

DRUCKER: Thank you, Zarina, sincerely. See you all later.