Stanley Kubrick

I explained to my colleagues at Warner Bros. that there was no way that this director was going to be told how to move forward day by day. He was going to call all the shots.Terry Semel

Stanley Kubrick made some of the most dazzling films of the 20th century, works whose titles alone have come to represent filmmaking at its most astonishing, challenging, and psychologically spellbinding. The list includes Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), A Clockwork Orange (1971), and The Shining (1980). A true auteur, he was meticulous, formally inventive, and philosophically provocative. Contradictions marked his career: a Jewish kid born in the Bronx in 1928, he spent the last decades of his life in England; a maker of Hollywood studio films like Spartacus (1960), he exhibited a fiercely independent sensibility. Right up until his sudden death from a heart attack in 1999 at age 70, he was still obsessing over the smallest details of his final film, Eyes Wide Shut (1999).

In November, a retrospective of his work opens at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The exhibition will include scripts, costumes, props, set models, and production photography and is co-presented by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. It’s an overdue show in a city whose main industry has been deeply impacted by Kubrick and his legacy. Festivities begin with LACMA’s second annual Art + Film Gala on October 27 (where the artist Ed Ruscha will also be honored), and continue on November 7 with “An Academy Salute to Stanley Kubrick,” hosted by actor Malcolm McDowell, who starred as the antihero Alex in A Clockwork Orange. The retrospective allows cinephiles to appreciate the dark vision—and the stylistic bravura—that evolved from early low-budget films like Killer’s Kiss (1955) and The Killing (1956) to the cult classic The Shining. Few filmmakers can boast a career that includes the antiwar classic Paths of Glory (1957), the controversial Lolita (1962), or the disturbing Vietnam War drama Full Metal Jacket (1987).

On the occasion of the LACMA retrospective, two of Kubrick’s friends and collaborators reminisced about the master director’s approaches, rituals, and concerns. Tom Cruise, who starred in Eyes Wide Shut, and former Warner Bros. head Terry Semel, who oversaw the production of many of Kubrick’s films, got together for a phone conversation that I moderated in late August to discuss Kubrick’s brilliantly cinematic storytelling. Some surprises emerged as they talked with affection about his renowned perfectionism: He was “incredibly collaborative,” according to Cruise; “Stanley was really our father,” said Semel, who consistently supported Kubrick and gave him unusual latitude throughout the studio process.

Kubrick loved baseball, chess, photography, and control. Cruise and Semel recalled how funny he could be—as well as how secretive—and remembered the groundbreaking qualities of his films. Love and gratitude are not the first words that come to mind when discussing Kubrick’s films, but they are the emotions that spring up in the people with whom he worked so diligently and closely.

ANNETTE INSDORF: Do you think Stanley Kubrick’s enduring reputation as a master director comes primarily from his artistic and technical skill? Or is it something beyond—his vision of the world?

TERRY SEMEL: I think it’s the latter. Tom and I can both vouch for the fact that anyone who worked with Stanley just adored him. He was a real gem, very smart, very articulate—

TOM CRUISE: And very funny.

SEMEL: Yes, he had a great sense of humor. I remember when working on the film that turned out to be Barry Lyndon [1975], I explained to my colleagues at Warner Bros. that there was no way that this director was going to be told how to move forward day by day. He was going to call all the shots. He did everything himself. He not only shot the whole movie, but there was almost no other crew on his sets except the key actor. So the way he worked was risky. It was questionable. But Barry Lyndon was the first in a series of movies we worked on together and it set up a routine that we kept for the rest of our projects.

CRUISE: Terry, you’ve got to tell them the ritual you guys had. I love this.

SEMEL: The ritual never changed. Because I was the head of the studio, I felt I had to make the decision that there was no way to put handcuffs on Stanley. So this was my routine—it was quite simple. Stanley would work on a couple of screenplays and when he thought he had the one that he was really excited about doing for his next picture, he would call me and say, “How fast can you come to London?” He did not want to send the script to the studio in California. Because he got a lot of death threats after A Clockwork Orange was released, he didn’t want to leave the area of London. So I would fly to London. His brother-in-law would put me in the same room in the same hotel each time. Then Stanley would get on the phone and say, “Make sure you go to sleep early now, Terry, get a lot of rest. Sleep well, don’t go out at night, just stay in your room, and in the morning when you wake up, there will be a script under the door for you.” [Cruise laughs] His brother-in-law would deliver the script in an envelope. I’d say, “Stanley, I really would like to discuss this script a little with a few of my colleagues at Warner Bros.” But he’d say, “No, no, don’t let anyone read the script! That’s why you came all this way. You read the script.” Okay. So I would read the script and when I finished, I’d call his house in the countryside and he’d send a driver to get me. And that routine never deviated. When he thought the script and the characters were there, my role was to show up, be there, read it, be familiar with it, and be in a position to say, “This is too expensive and this isn’t” to all the important details of the film.

INSDORF: And those details extended to the casting of the film?

Stanley was brilliant at getting under the audience’s skin. He was very interested in the idea of, ‘How can I tell this with just a camera?’Tom Cruise

SEMEL: Well, when Stanley did The Shining, he had someone else shoot a lot of second unit because that was in America. He would not fly to that set. Most of the interior filming was done in the studio in England. One of his great concerns was Jack Nicholson—a terrific actor and a big movie star, but Jack never went to sleep at night. He was always out socializing, having fun. Stanley thought that was terrible. He thought an actor had to go to bed early, get a good night’s sleep, and come to work in the morning. So after The Shining, Stanley would say, “I don’t want to use movie stars in my movies anymore. Jack Nicholson was fabulous but he was always out partying and I don’t want to do that.” He even said that about Tom on Eyes Wide Shut. And I said, “But Stanley, I want to have a movie star in Eyes Wide Shut. I mean, it’s been a long time.” He said, “No. They have too many opinions.”

CRUISE: [laughs] Too many opinions. And he doesn’t want opinions.

SEMEL: Not until he trusts the person and realizes they are going to contribute positively toward the film. I said, “I want Tom Cruise.” And Stanley said, “He’s not going to fly all the way here.” I said, “Hold on. Give me the phone.” And I called Tom and I said, “Tom, I’m sitting with Stanley Kubrick. I think this is a fabulous idea and a great movie for you and it’s a great movie for Stanley. Would you consider the idea of coming to London and meeting Stanley Kubrick and talk about Eyes Wide Shut?” And Tom said something like, “I’ll be there in the morning.” And as it happened, they became two brothers—or a brother and a father. Stanley isn’t like how others imagine he would be, but he didn’t like to meet many people. So he didn’t use a lot of movie stars in his pictures.

INSDORF: But he used Kirk Douglas in Paths of Glory. In fact, the only way Kubrick was able to make Paths of Glory was to have a star—Douglas—take the role.

CRUISE: And Ryan O’Neal was in Barry Lyndon. And he actually offered Paul Newman [2001: A] Space Odyssey. But for me, it was so interesting hanging out with Stanley and being able to spend time with him. When I first met him, he was an incredibly charming guy. I remember I took a helicopter and landed on his property. And I read the script for Eyes Wide Shut, which was about 95 pages long. It was a very simple story. We sat down and he made lunch for me at his house and we spent about four hours in his kitchen talking. We talked about the story and where he wanted to shoot it and how he wanted it to go. He said, “Look, I need to start shooting this right away in summer because I want to finish the movie by Christmas. Okay?” Of course, I had studied Stanley’s movies and I’d spoken to many people about the way he works—especially Terry—and I knew it was going to be at least a year of shooting, at the minimum. So I said, “Okay, Stanley, let’s do this.” Then we talked about the female lead and I said, “Listen, I don’t know if you’ve seen Nicole Kidman’s work, but you’ve really got to look into her. She’s a great actress.” And we kind of talked about the wife, and Nicole playing that character. He also talked about baseball. He loved baseball.

SEMEL: That’s right.

CRUISE: He started as a photographer at Look magazine. We discovered that we were both Yankees fans. But in that meeting, he didn’t really want to discuss certain subjects—like how he made certain pictures or the choices he made. But as time went on, we became great friends, and he just broke down for me all the sequences of his movies—starting with 2001—and how he came up with all the ideas for each shot. It was an incredible learning experience. Working with Stanley was a lot of fun because even though it may look like a very simple film, he was brilliant at getting under the audience’s skin. He was very interested in the idea of, “How can I tell this with just a camera?” I know the games that he and Sydney Pollack used to play back-and-forth. They would trade commercials back-and-forth and see how much of the dialogue could be taken out of the commercial while still retaining a story and also seeing what they could do visually with it. When you look at Eyes Wide Shut, there’s the sense of, “Is this a dream or is this a nightmare?” and how do you handle the aspects of the story in such a way that you’re not resorting to the usual visual techniques to say, “This is nightmare.”

INSDORF: You mean Kubrick was playing with formal structures?

CRUISE: He was pushing the film very hard. One fascinating thing about Barry Lyndon was that he used the Apollo lenses [still photography lenses developed for NASA, modified for film use]. The speed of those lenses is startling, and he used them to shoot in candlelight, which gives it that incredible depth of frame that he’s really known for. He likes those wide-angle lenses and he would often adjust the furnishing and the pictures on the wall. He understood those lenses completely, because a lens like that will bend the picture. It will alter it, and he made adjustments because he wanted that depth, he wanted the audience to feel the space. He was very selective when he went into a close-up. Every director has his taste in a performance, but Stanley would explore a scene to find what was most interesting for him. When you look at the lens choices with Jack Nicholson, for example, when he’s in the pantry leaning against the door and Stanley shoots up at him, its clear what an amazing eye he had. When you’re working with a filmmaker with that command of storytelling, you know right away that it’s his taste, it’s an extension of him. It’s not necessarily analytical. As an actor—like an artist—you have to ask, “Why do I choose a certain moment to play something a certain way?” It’s organic to who we are. I think you see through Stanley’s movies that his visual command was an extension of him. And in Eyes Wide Shut he was very much pushing the film. Every morning, I would go in early and we would look at the negatives together. We would look at the day’s rushes—not with sound, but we would look at the image, and he was checking the film to see how hard could he push it. There was an interesting moment during filming. We were shooting in the backlot of Pinewood Studios and he had built a set to resemble New York. We were working on a scene where I see that a guy is following me. He cast a very distinct-looking actor, a bald guy with a very particular wardrobe. In the shot, this guy walks across the street. We went back and looked at the video playback; we must have spent hours studying it, just to figure out what the behavior of this man should be like crossing the street. Finally, Stanley said, “Listen, when you’re crossing the street, please don’t stop staring at Tom.” It looks like a very simple thing, but behaviorally, it had a tremendous effect. He just immerses you with his tone. His tracking shot through the trenches in Paths of Glory is revolutionary. And it’s the same with the Steadicam shot in The Shining with [camera operator] Garrett Brown. That was a very difficult shot where the boy is racing from carpet to floor to carpet. That was the brilliance of Stanley: he knew how to use the medium of film and the camera and the lens, and, of course, also sound. He had such command of his craft.

SEMEL: Tom, were you amazed by how few people he had on the set?

CRUISE: Yeah. In all matters of the film, he was economical. He needed time to make the film, yes, but he also needed time to think about the film. The script, for him, was just the blueprint. And, as you know, as much as Stanley projected this notion of him as not being collaborative, he actually was incredibly collaborative. We had a $65-million budget for Eyes Wide Shut, and everyone thinks we ended up shooting for two years. But it wasn’t quite two years. I got there in August and he gave us a month off for Christmas and left about a year and a half later. But we had a lot of vacations in between. Stanley would allow us to break, and that would give him time to evaluate the film and look at the sets. So he knew what people he needed. And he was very smart about money. He never went back to Terry and asked for more. He stuck by the budget and did everything it allowed him to do—with the time he needed—to make his film.

SEMEL: I don’t think it can be overemphasized how hands-on he was on his projects. He never became the type of filmmaker to direct from a distance.

CRUISE: Earlier on in his career, he would do all the operating. When you look at The Shining, you see that he operated a lot. He did less so on Eyes Wide Shut, but even then, he didn’t want many people on the set. He wanted to keep it very contained and very intimate and personal. It was the least amount of crew I’ve ever had on a movie. I think he was always looking at “How do I bring things down to a simplicity?” Annette, you spoke about Paths of Glory. After that film, he went on to work with Kirk Douglas again on Spartacus. The original director for Spartacus was Anthony Mann, but Douglas replaced him with Stanley after the first week. And, of course, Stanley and [director of photography on Spartacus] Russell Metty didn’t get along, because Stanley, of course, really knew as much, if not more, about lighting and composition. Metty was used to, “You’re the director and you stand over there and I do my work over here.” He and Metty really came to blows on that. I think that experience changed Stanley’s feelings about Hollywood in terms of not wanting to go through that again.

SEMEL: I remember he would finish a film and come to me and say, “I, Stanley, want to create all the ad campaigns. I want to do all the PR. I want to be involved in every aspect of the movie.” He worked on every inch of how a movie got promoted. He did the trailer. He decided when it was going to open, and in which city. And all of this was done with the backdrop of, “No, I cannot leave London or the greater London area.”

CRUISE: The trailer for The Shining is stunning. And I think the one for Eyes Wide Shut is as well.

INSDORF: I remember François Truffaut telling me about 30 years ago that Kubrick had a hook-up in his home that alerted him when a projection bulb blew in a New York theater that was showing one of his films. This was before computers were part of our daily lives. Was he the most exacting perfectionist with whom you’ve ever worked?

SEMEL: Without question. He would get a list of the theaters that his movie would be opening in, and he would have his brother-in-law go from theater to theater taking photographs. Stanley was interested in how many people there were in the audience when the movie opened. His brother-in-law would photograph them coming in and out of the theater. So Stanley knew more about what was happening day by day than I did. [laughs] He’d call and say, “You gave me a list of all the theaters and I have photographs of them. This one doesn’t have good parking and the screen isn’t very good in this theater in Denver!” I’d say, “How do you know about this theater in Denver?” So this was not a man who just went out and made a movie. It was sad in fact that the final night before he died he had been going over every detail of Eyes Wide Shut—the ad campaign, the trailer, everything—and it was only week or two before it all came out. He was so good at that aspect of promotion, but he would often make this comment about other filmmakers: “Why in the world do they go on talk shows? Do they realize that they’re not celebrities? They make movies. Why are they there?”

CRUISE: He did not want to be a celebrity. You know, [the late director] Tony Scott worked on Barry Lyndon. He was in art school at the time. Tony told me that he wrote down the exact longitude and latitude of where Stanley wanted the camera, the exact height of the camera, and the time, to get the shot that Stanley wanted. Tony said he sat there for a couple of weeks trying to get the right light. Stanley really loved the Scott brothers. I’ve had long conversations about this with both Tony and Ridley. Stanley was a director who did not let people borrow or rent his lens. He never gave his Apollo lens to anyone. But when Ridley was having a really difficult time with the end of Blade Runner [1982], Stanley gave Ridley footage that he had shot but didn’t use for the opening of The Shining. He was offering to let him use it for Blade Runner. That’s how highly Stanley thought of them.

when you watch eyes wide shut, yes, it’s a disturbing film. but when we were shooting the end, stanley said, ‘this is a happy ending.’ we were in a toy store. he had an amazing sense of humor.Tom Cruise

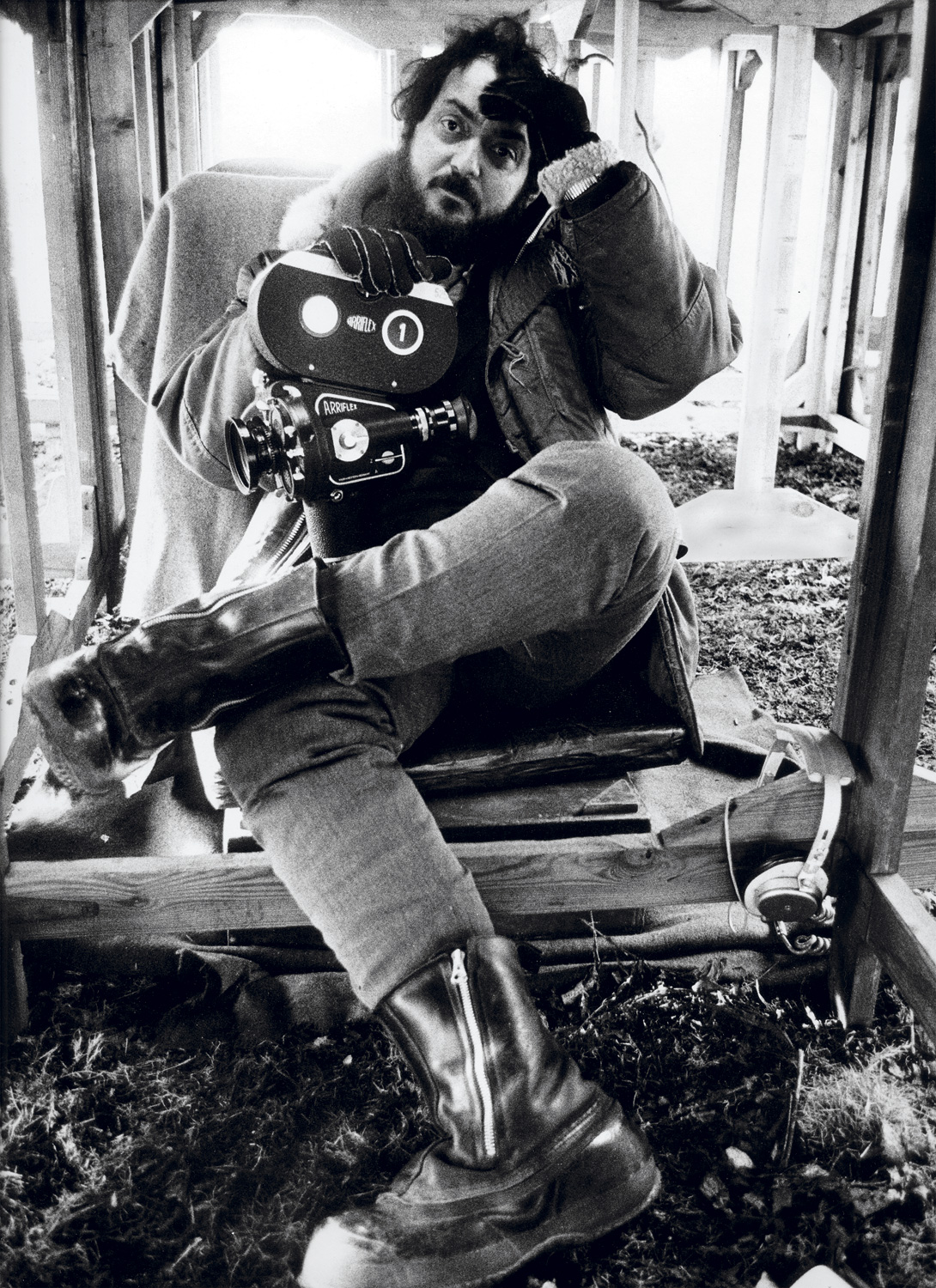

SEMEL: Stanley didn’t even like having his picture taken. Maybe it’s because my wife is British, but for some reason, Jane was the one photographer he’d let take his picture. Some of her pictures appear in the exhibit at LACMA.

CRUISE: Yeah, he loved Jane.

SEMEL: One of the pictures is of him and me. He’s in his old clothes, totally disheveled looking—

CRUISE: He wore the same thing to set everyday.

SEMEL: But the good part was, whenever he did allow someone into his private sanction, his home, he’d spend the entire day—or two or three—in the kitchen. And we’d eat.

INSDORF: I want to go back to something that you said, Tom, about his ability to get under the audience’s skin. In comparison to other contemporary filmmakers, his vision wasn’t upbeat or comforting. The choices he often made—a wide-angle lush exterior with a tiny human being in the center, or a crowded interior with few close-ups of the character, for example—give a sense of dehumanization. If you look at Eyes Wide Shut, the mansion is an arena where cold copulation is the norm and anonymity is the condition. Do you think that bleakness was an integral part of his vision?

SEMEL: He had a great sense of humor. I don’t think he saw any of that as being bleak.

CRUISE: In terms of the orgy scene, that’s how Stanley wanted it to feel. He wanted the audience to have that reaction. Here’s a guy going into the dark side of life. One of the themes that the film explores is jealousy—the wife never actually lived this fantasy that she had, and the husband goes on this journey where he feels, I’m going to do this. But nothing ever happens. He doesn’t sleep with the woman whose father has died. He doesn’t end up being able to participate in the orgy, and, as an audience, you wonder how much danger he was ever really in—you know what I mean? And yet, it does have to be dark. The character that I’m playing—and Stanley and I spoke about this—is using his title as a doctor as a way to open doors and as a weapon. Stanley’s own father was a doctor. People look at doctors like they know everything, and Stanley was very cynical about that—people using their titles or power to allow themselves into places and to exploit others and the situation. And the orgy is dark, but it’s not satisfying either—it’s a slow burn. In The Shining, there is the same slow burn. There is no cat that jumps out at you. It’s a slow, slow burn that gets under your skin, and it builds and becomes quite terrifying. He’s someone who definitely understood the tone of the story that he was telling and the consistency of tone. So I think, personally, when you watch Eyes Wide Shut, yes, it’s a disturbing film. But when we were shooting the end, Stanley said, “This is a happy ending.” We were in a toy store. As Terry said, he had an amazing sense of humor. And he was a lot of fun to be with.

INSDORF: I’m thinking of the subject matter he was drawn to. [Anthony] Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange, Full Metal Jacket, The Shining—all of these are unsettling visions of human behavior. Remember that scene in A Clockwork Orange where Malcolm McDowell’s character has his eye clamped open, forced to watch horrors? His voice-over says, “It’s funny how the colors of the real world only seem really real when you viddy them on the screen.” Kubrick seems to be suggesting the relationship between film and the spectator is both sadistic and humanizing.

SEMEL: I think you’re right. He was the man who made Lolita. Did he have a smile on his face the entire time he did Eyes Wide Shut? Who knows?

INSDORF: Terry, was there any serious thought of releasing Eyes Wide Shut as an NC-17 film with no digital covering of nudity?

SEMEL: It was such a short period of time between Stanley’s death and the release of the film. I did not want our company to be responsible for changing Stanley’s view or adding things to Stanley’s view. I just decided in my own self that I was going to do everything I possibly could to make sure that the film got this rating. It’s Stanley’s movie. And I don’t want anyone else touching it or fooling with it. I don’t want to change history with it. I think the best parts of the film still shine. I just made sure that we got the rating so it could be in lots of theaters throughout the world.

CRUISE: Stanley wanted that. He wanted his movies to be huge successes. He did not want an NC-17 rating.

SEMEL: He would call me every other week to tell me to go back to the rating board. [laughs] To push them against the wall . . . Tom, do you want to talk about the final nights before he died?

CRUISE: What happened is, Stanley sent the final cut of Eyes Wide Shut to New York. And the four of us watched it—Terry and Jane and me and Nicole. We watched it twice in a row and went out to dinner after that. I had to leave after that for Australia to start filming Mission [Impossible 2, 2000]. You were on the phone talking with Stanley about the movie, going over everything—

SEMEL: That’s right. Stanley wouldn’t allow anyone else to see the cut. I think his nephew carried the print from England to a screening room in Manhattan. And he called that night—”What did you think? And how was this? And how was that scene?” He went through every bit of the film. And generally speaking, we were all very happy and excited. I said, “Stanley, I’m going to fly back to Los Angeles,” which is where I was living. “We’ll continue this tomorrow. We’ll talk about lots of details. You have notes, we have notes.” And then when tomorrow came, he was on the phone with me—which was not a rare occurrence—for many, many hours. And it was probably about three o’clock in the morning at that point, and he and I had been talking the entire time. And he went over every detail of how the movie would be released—of who would do it, of what it would look like, etcetera. It just went on and on and on. When it was about four o’clock in the morning, I said, “Stanley, I’m really tired. I’m going to go to sleep now. We can continue this conversation in the morning.” So I go to sleep, get up in the morning, and in those days we had an answering machine, and there were dozens and dozens of calls on the machine, starting with Stanley’s wife, who was insisting that they wake me up. He had died during that night. She said, “What was it like? What happened? Were you guys angry?” I said, “No, we were laughing for hours. We were going over everything on that film and we were in hysterics for hours—for many, many hours until sunlight was starting to come through.” We were all in a state of shock. I’m so happy to say that his life ended on a huge up-note of feeling success coming from his latest movie, Eyes Wide Shut. It was like a celebration on the phone for many, many hours and a lot of laughing. Later, we did an opening for Eyes Wide Shut for a charity in Los Angeles, and I got up to introduce the movie to the audience, and I said, “This is going to be my last movie at Warner Bros.” I think all of my colleagues and the whole company all stopped to say, “Terry, what did you just say?” I just felt there’s no way to top the experience with Stanley. And then didn’t we all fly back to his funeral in his backyard?

CRUISE: Yeah, we did. I was in Australia when I got the call. I talked to Stanley on the plane. We talked for about an hour, going through the film. And then I got the call. And we flew back for the funeral at his house in England.

INSDORF: Had Kubrick lived another 10 years, which films do you think he would have made? Would it have been A.I.? The Aryan Papers? Napoleon? What are we missing?

CRUISE: We talked about Napoleon and A.I. He showed me the boards for both of those films and he was very interested in them. But with Stanley, you never really knew what he was going to do.

SEMEL: And The Aryan Papers. He’d been thinking about how to do a film about the Holocaust for a few years. And then one day, in one of those little sessions in his kitchen, I said, “Are you aware of Spielberg’s film [Schindler’s List, 1993]?” And he was not really aware of it at the time. As we talked about it, Stanley said, “I don’t want to do it—he’s way ahead. Steven’s film is going to be coming out very shortly.” And he switched. He started to look at other scripts he had been working on and other properties that he was interested in.

INSDORF: So Schindler’s List prevents him from making The Aryan Papers. And, ironically, Spielberg picks up the mantle and directs A.I. [2001].

CRUISE: They were working on that together.

INSDORF: Tom, as you’ve worked closely with Spielberg, how different do you think Kubrick directing A.I. would have been from Spielberg directing it?

CRUISE: They’re just different directors. Both amazing, extraordinary filmmakers. It’s impossible to say, as they would have made different choices. I know that Steven wanted to honor Stanley, and that has a lot to do with why he made it.

INSDORF: I admire A.I. a great deal, but I get the feeling that Kubrick would have made it darker than Spielberg did, consistent with some of the vision that I’ve been describing from his previous work. Maybe there is something to the fact that he loved chess in addition to baseball and photography. He was the master manipulator on the one hand, and he often depicted characters as pawns—as diminutive shapes on an elegant chessboard of life, moved around by forces that we’re not aware of—and I think he may have felt that more than Spielberg ever would. But, yes, who can say. From all I’ve read, Terry, your relationship with Kubrick was extraordinary for him in terms of the support. The unconditional support you showed is rare in the history of American cinema.

SEMEL: It’s also very rare to meet a person with his capabilities and his intellect and a great sense of humor at the same time. I think Tom would certainly agree that he became our idol, he was the man. Whichever direction he wanted to go with his next movie, from my standpoint, that would be his next movie. And I’m thrilled about this exhibition on him at LACMA.

INSDORF: It’s thrilling to be able to see all of these films together, including some that haven’t gotten their just attention, like Full Metal Jacket, which suffered a little bit in comparison to a film like Platoon [1986]. But that also underlines how Kubrick was different from other filmmakers. Platoon offers you the possibility of identifying with the Charlie Sheen character, who ultimately chooses good over evil. But in Full Metal Jacket, the character played by Matthew Modine has this amorality that you can’t really sympathize with, and, in that sense, Kubrick was more challenging than most filmmakers who’ve dealt with difficult subject matter.

CRUISE: The thing about Kubrick, though, is it wasn’t analytical for him. These are things that he just did. I don’t think he went about it thinking, I’m going to do it like this for a particular reason. In the end he really was collaborative. I felt like we were working on Eyes Wide Shut together.

SEMEL: Don’t forget he looked at you as a colleague, and a friend, and someone who he could also trust. I’m sure Jack Nicholson today is still thinking, “Why didn’t he trust me?” [laughs]

Tom Cruise is a producer and the star of the film Jack Reacher, opening this December. Terry Semel is the Former Chairman and CEO of Warner Bros. and the former Chairman and CEO of Yahoo! Inc. Annette Insdorf is Director of Undergraduate Film Studies at Columbia University. Her most recent book is Philip Kaufman (University of illinois).