Drag Artist Silvero Pereira on Getting Blood-Soaked in Bacurau

The first thing we learn about Lunga in the Brazilian film Bacurau, played by Silvero Pereira, is that he is wanted; he and his gang attacked a water source being kept from their village. This is the village of Bacurau, both the film’s title and its nucleus, a matriarchal community with a reverence for psychotropic drugs and free will. Though the town is an invention of directors Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles, we are told through an artificial drone shot that Bacurau is located in Northeastern Brazil, the countryside, and the story takes place “a few years from now.”

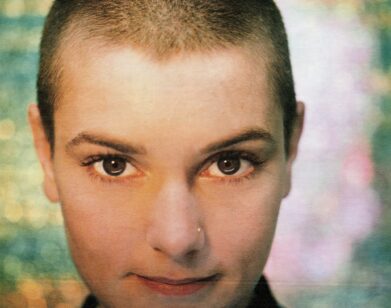

Author Carol Mavor writes that cinema is “unstoppable real time, reeled over and over, as if caught in an endless quest forward, even when it is depicting the past.” Bacurau rushes to meet the near future in all its disturbances, following the dangers of globalization and advancing technology as deployed by the wealthy landowners who have long reaped disproportionate advantages from state systems. Lunga is the town’s strife and ideology in revolutionary warrior form, Bacurau’s black-fingernailed savior in gold rings and bracelets. He is the person who gets bloodiest when the town’s existence is threatened. After Bacurau‘s premiere at the 72nd Cannes Film Festival, I saw Pereira, a Northeastern Brazil-bred theater artist who works mainly in drag, on the red carpet as his alter ego Gisele Almodóvar wearing a cotton-candy-colored gown that exposed a warning sign tattoo. I was not surprised to find out that Silvero’s political work in Brazil is as radical as Lunga’s—both committing their lives to achieving equal resource distribution, and equal respect, for their communities. Though Silvero, of course, is a little less soaked in crimson.

———

BESSIE RUBINSTEIN: One of the film’s successes was the invention of Bacurau itself—the town as a living, breathing organism. How did you, and the rest of the cast, go about understanding your places in this community you were creating? How did the ensemble work on developing that aura of kinship?

SILVERO PEREIRA: Yes, it’s an invented place, but it is full of references that are very close to us and there’s a lot of political issues and issues of prejudice. And a lot of the characters in this place have a very common relationship with it, a relationship that represents feelings about the countryside of Brazil. My character, for example, has a very close relationship with many of the people that left a place, left their town because they don’t agree with certain things that happen there, so they prefer to be in other places. So we felt very close to this in the cast.

RUBINSTEIN: Speaking of the references to and critiques of Brazilian politics, which are quite layered, I read one critic’s opinion that the film demands intellectual labor of the viewer—because you appreciate Bacurau far more if you know Brazilian administrative policies towards the environment, for example, and the Latin American tradition of banditry as resistance. The film is direct in its address of its own national politics, and unapologetically unwilling to simplify. And this critic felt that that took away from the film’s enjoyment. What would you say to that?

PEREIRA: First, this isn’t specifically about the current government. It’s about the government that we’ve always had. This film was written and produced well before the election of Bolsonaro, so it speaks about a very common type of politics, specifically about the coronéis, the landowners. They think that they own everybody. It’s a very macho type of politics. So I think the universality of the film is in the resistance of these populations and communities who feel affected by this and not valued. And they find that the great power is in the people and they try to demand and require that these governments work for them.

RUBINSTEIN: Which you would think is a universally relatable dissonance to depict.

PEREIRA: When I watch films like Bacarau, or Parasite, or Joker … when I watch them, I identify immediately with the issues that they portray no matter where they’re from.

RUBINSTEIN: Lunga is queer. And you talked the directors of Bacarau out of writing him as a transgender character, as he was originally conceptualized, for purposes of representation—you wanted the identity of the actor playing Lunga to match the character, and you don’t identify as transgender. You personally prefer an identity not confined to a label, though of course you recognize their productive power. Do you extend the fluidity that you practice in life to your dramatic work?

PEREIRA: Yes, for 17 years I’ve been doing this specifically in theater. I am part of a collective of artists in my city of Fortaleza that is called As Travestidas which translates as “the Transvestites.” And we just discuss issues of gender. It’s a collective—it’s not just a theater group because we also do dance and music. And we also have a Carnaval parade that we do. So we question and provoke on these issues of gender and what is right and also what is in tension or disagreement with this. And I think when we build this with respect for differences, we have a better society. So I’ve been working with this for 17 years.

RUBINSTEIN: So what kind of relationship do you see between drag performance, on camera performance, and non-drag theater performance. Where are the distinctions, if they exist? If someone else has written a role that’s not a drag role, can you apply aspects of drag?

PEREIRA: Yeah, so I have a degree in the theater arts. And during my studies, I really thought about how drag as an art form, as an aspect that is a part of the theater arts, it’s a genre of theater arts. And just the act of creating your wardrobe, and performance, and memorizing songs and lip syncing them with so much feeling is definitely a theatrical craft. So I think that there’s no difference really between watching a play or performance piece or drag show. The only real difference is that they’re in different spaces. I think they all fit within the umbrella, the grand umbrella of the performance, theatrical arts. I do a lot of work in TV and film that has required that I be in drag, that I do drag work. But I also do a lot of work that has nothing to do with drag. And I don’t really mix the two.

RUBINSTEIN: I read that a part of your work’s purpose is dedicated to getting the Brazillian public to recognize drag as a high art. How do you feel about the current attitude towards drag—its perception as an artistic form?

PEREIRA: Here in Brazil, there is a very big difference between issues of gender and the art of drag. So I usually say that when we talk about drag as an artistic identity, that doesn’t have anything to do with sexual identity. I think they are two things that are very different. So do you need to be LGBT to be a drag queen? No.

RUBINSTEIN: They’re often made synonymous. Bacurau is a place where sexual identities aren’t regulated … aside from that, the town has something in common with your hometown, Mombasa, in that they’re both sun-baked communities in the Northeast. Would Bacurau be a utopian community in that sense?

PEREIRA: Yeah, it’s exactly in this aspect that the community represents a certain ideology. Something that is not incorrect. So this aspect doesn’t interest the members of the community who you are in a relationship with. What is important is having respect. So you have a trans woman who’s married with two men. You have a revolutionary figure who has left the town. You have a doctor, a woman doctor who is very important, and she is in a homosexual relationship. You also have a woman who arrives at the town with the death of the elder. And so the figure of the woman is very important in this film, but also respect is very important. Relationships are not the principle focus of the film. It’s really politics, and the big villain of the film is the political system, not the relationships.

RUBINSTEIN: One of the main political ideas of the film seemed to be a warning that technological advancement should not be met with excitement, because when power is distributed unequally technology will inevitably be used against those with less power, and used to constrain them. What are your thoughts on the possibilities of technology for liberation?

PEREIRA: I think that technology needs to be democratized. And that is really the biggest thing that comes to me when I watch this film, how much it is necessary and how it is utilized to communicate and to try to solve and deal with the problems. The community tries to use the technology as well, but this effort is reduced by the fact that other people have technology that is much greater than the people in the town. And so the people on the community don’t have access to the same technology. They only have access to a part of these things. And the people in power still take advantage of this.

RUBINSTEIN: In Brazil, artists are often viewed as leeches, non-workers who don’t contribute. But Bolsonaro’s administration, of course, got rid of the ministry of culture and puts artists on trial for subversive exhibits. Could you speak a little bit about that hypocrisy: treating the arts as both worthless and powerful enough to be dangerous?

PEREIRA: I believe that art is possibly the most powerful weapon we have in our system. So when art decides to talk about something, it is because it is profoundly discomforting for people in their daily life—it’s something that’s profoundly bothering them. Art becomes powerful because it goes against political interests. So it doesn’t have too much political interference, and it’s different than other systems that are very much in control of the government, like systems of health or education, those things that the government can control. But the artist has a certain independence to produce. And they can be aggressive, and try to think horizontally, and from down to up and up to down, to build the story.

RUBINSTEIN: I wanted more scenes with Lunga, to know more about him, but of course this film is an ensemble piece. Did you imagine any history for him, or details about him and his life which don’t appear in the film?

PEREIRA: Yes! Lunga was constructed through long conversations with Kleber and Juliano. I enter the scene with a lot of backstory that the film cannot show. This character was built with a lot of subtext and every scene and dialogue is loaded with this background, from a past that has not yet been presented. I admit that I hope for a sequel to Bacurau, or for the opportunity to show more of Lunga and his past.

RUBINSTEIN: Please! The film definitely doesn’t glorify violence, but it still presents violence as a means of survival—maybe the only means of survival—for the people of Bacurau. What is your personal philosophy about violence versus pacifism in the pursuit of democratization?

PEREIRA: I don’t believe in violence in any circumstance. Bacurau is fiction, so what we should take from it are the desires to welcome, to care for, and to preserve history; to not forget the past, our origins. Not a single character at the end of the film is content with what they had to do to re-establish the “peace.” I really believe in this, we have millions of possibilities for talking, understanding, and building spaces of equality. However, we must remember that violence comes from the powerful, and we do, in fact, need to know how to defend ourselves.

RUBINSTEIN: Bolsonaro makes it difficult to forget. To say that he would rather his son be dead than gay is nothing short of a sort of violence. Has your will, your drive to continue the work you do for your community, suffered under this administration, or has it been strengthened?

PEREIRA: Our LGBTQIA+ community is suffering a lot with this government — they are trying to take away all of the rights that we have achieved until now. However, in the last 13 years, opportunities were created that strengthened our struggles and allowed us to build spaces in art, politics, education, and health. I believe that we are strong and we will not go back. If necessary, we will “bacurize” to not lose the rights that we have achieved. Black people, LGBT people, women, Indians, the poor, and Northeasterners are the majority in this country, and our nation has an obligation to build historic reparations with these communities.