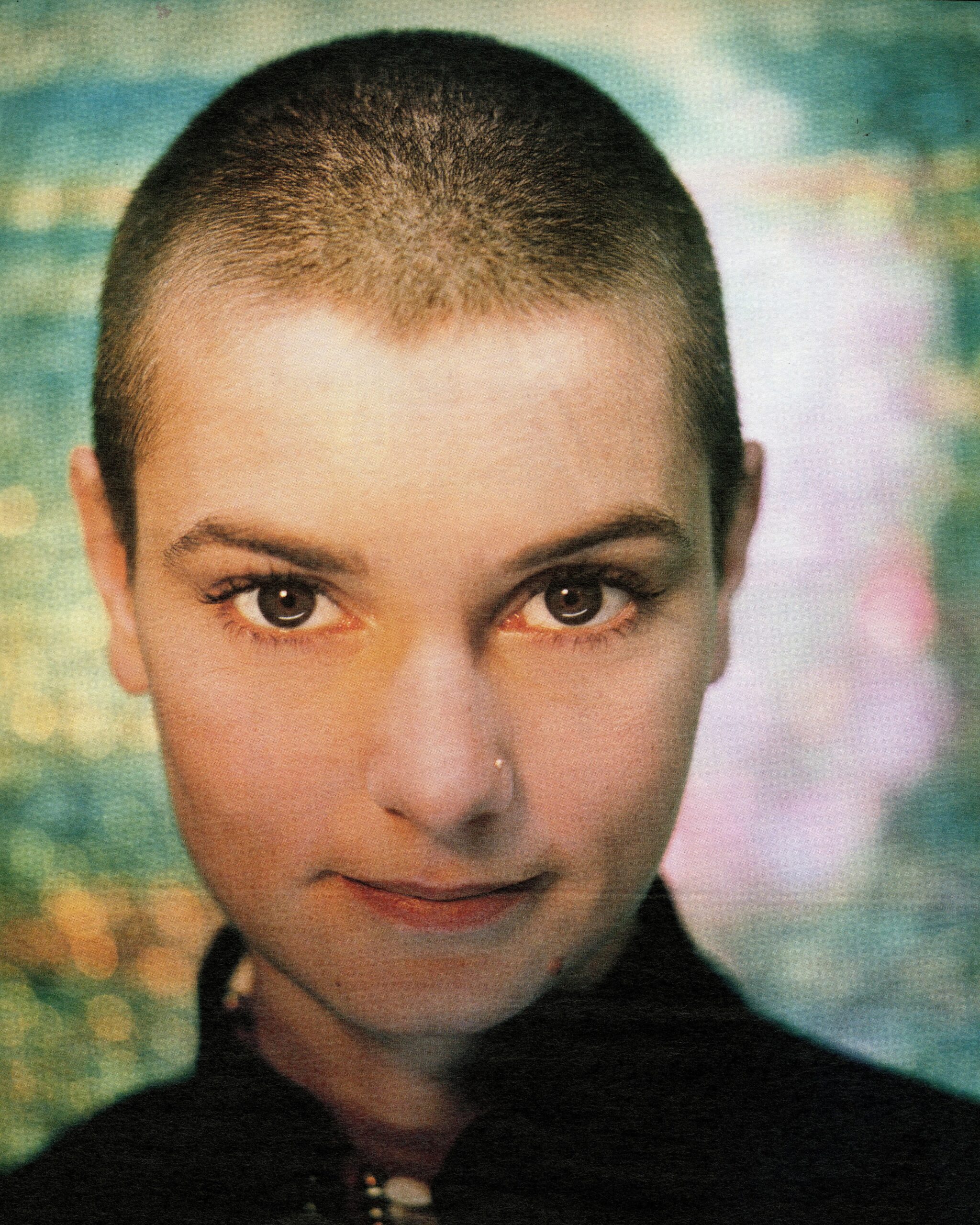

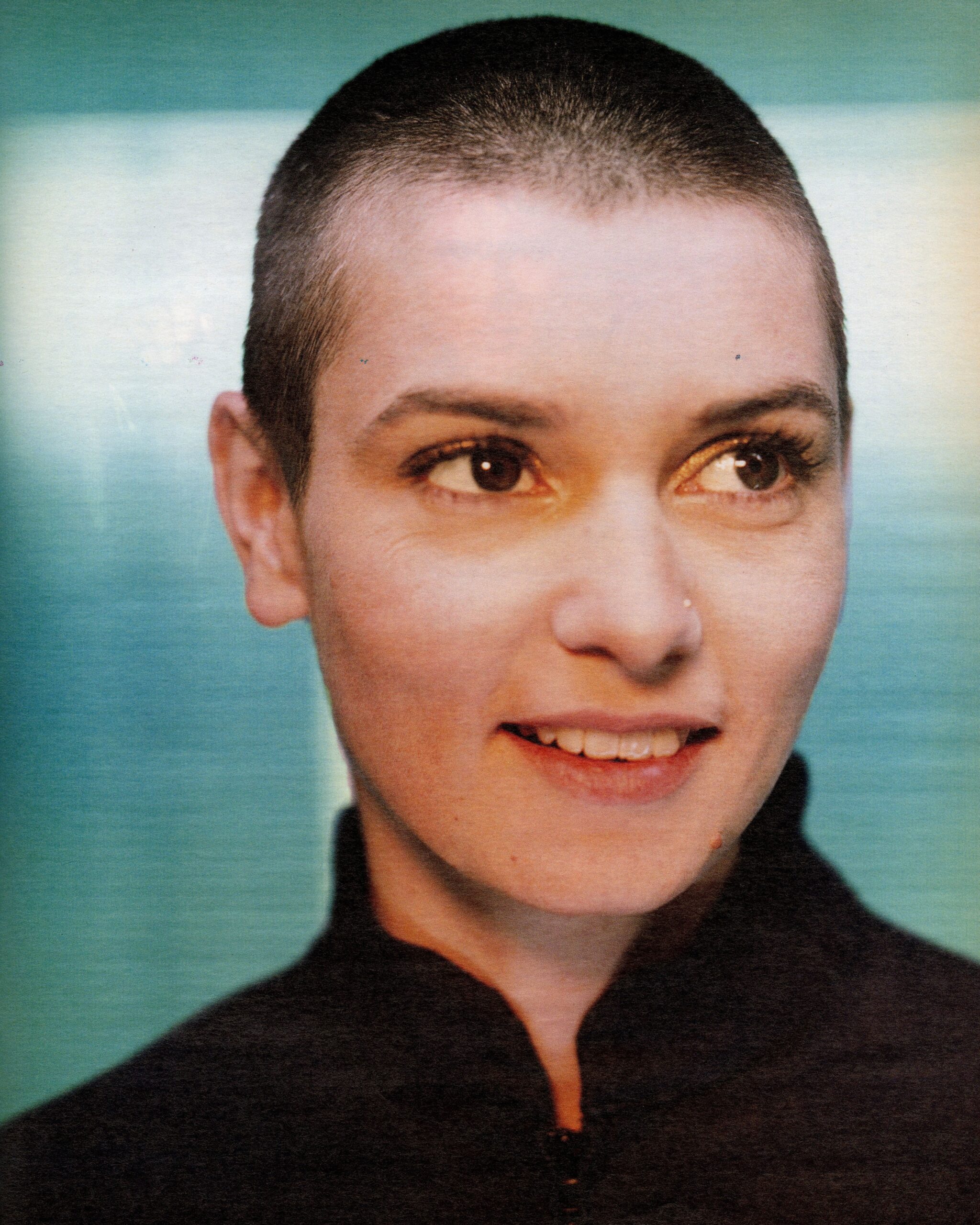

ICON

“Sinéad Belonged to No One”: An Exclusive Excerpt From Nothing Compares to You

Sinéad O’Connor’s voice is immortal. Exactly two years since the Irish singer-songwriter’s death, her music lives on as a balm and a rallying cry for those who need it. O’Connor, of course, was just as much an advocate as she was a musical icon. Tomorrow, Simon & Schuster will publish a dynamic collection of essays called Nothing Compares to You: What Sinéad O’Connor Means to Us, an ode to her complicated life as an activist and artist featuring pieces by Neko Case, Porochista Khakpour, and Rayne Fisher-Quann, whose essay “Sorry for Disappointing: ‘Daddy I’m Fine’,” is excerpted below. O’Connor, writes the Canadian critic, “serves as a reminder to me that some lives, even when vastly different in their particularities, have similar shapes, and that certain kinds of women have been carving their lives into inconvenient shapes for as long as anyone can remember.”

———

The day that Sinéad died, my father cried alone in a bar in Quebec. I know this because he texted me about it, said the French-Canadian bartender didn’t understand at all when he tried to explain why, and then sent me a link to the song “Daddy I’m Fine.” “This song always reminded me of you and your sibling,” he said. I could tell that he was still crying. And then, five minutes later, a follow-up text: “To be clear, there are some lyrics in that song i absolutely DO NOT associate with you.”

He had to say that, of course, in the name of fatherly couth—there are a lot of lyrics in the song about pushing your boobs up and wanting to fuck every man in sight and so on and so forth. But the beauty of the song, the source of its triumph but also its hidden complexity, is that it’s all much more about wanting than it is doing. She isn’t singing about actually being promiscuous, per se (at least not yet); she’s singing about how badly she wants to be able to act like she is. She sings about wanting to feel sexy under the lights, to slick back her hair, to dress like the kind of woman who might implore a guy at the bar to come home with her. It’s a song about the part of your life where the whole world stretches out before you, perilous but wide, and you’re stuck with the beauty and the terror of trying to choose what kind of person you might be once you’re in it.

It’s also a song about dropping out of school and leaving your hometown to be an artist in a big city, which is precisely what happened to me in the years before my father texted me from the bar in Quebec, so it’s not surprising that he thinks of me when he listens to it—he who has been on the receiving end of countless long-distance phone calls in which I probably whined the words “Daddy, I’m fine” verbatim. But even with all of its technical relatabilities, the crux of my connection to the song is much more about the former feeling, the one that’s harder to pin down: the feeling of aching for a new world, aching to be a different kind of person, wondering if it’s possible to try on the trappings of a life before you’re ready for it and turn into the person you want to be along the way. I’ve never exactly wanted to fuck a random guy at the bar, but I want, almost constantly, to know what it must be like to be the kind of woman who would.

Faith and Courage came out a year before I was born, and my mother, a devoutly feminist ex-Catholic who left her hometown in her late teens and the Church when I was a baby, listened to it with religious fervor throughout my childhood. The text from my father was a reintroduction that came at a serendipitous time: it was days after a breakup with my long-term boyfriend, a good man from my hometown who I loved dearly, who I lived with, who gave me a comfortable life, and who I left because I felt in my stomach that I had to be by myself in a place I’d never been before or my life might be for nothing. It was one of those rare and precious moments where a work of art reveals itself to you at precisely the time you need it most. In the months that followed, I listened to “Daddy I’m Fine” on loop, nonstop, on the plane to LaGuardia, as I went to sign my first solo lease, on my walks home from parties full of strangers. I’m fine, I’m fine, I’m fine.

But as good as it feels to relate to a song like this one, relatability can be a kind of trap. Good art helps you understand yourself, and great art feels like it becomes a part of who you are, and both of those experiences create deep, real intimacy without proximity—without real knowledge of the person on the other side of the transaction. When art and its artist feel like they are speaking not just to you but in some way from you, it’s easy to feel like they belong to you; like their words, and by extension their life, are just as much yours as they are theirs. But Sinéad, perhaps more than anyone, belonged to no one. And so I keep having to remind myself that I don’t really know Sinéad. To try to write about someone else’s art just by consuming it is a bit like trying to draw someone else by looking at them through a two-way mirror: the result will always look at least a little like you.

Like Sinéad herself, “Daddy I’m Fine” is full of contradiction. It’s a song written in part from the perspective of a person in the distant past, and as a result, we’re given a kind of contextual omnipotence over the version of Sinéad whose story we’re hearing—we listen to it knowing what happened to her after she moved to London, about her struggles with fame, about her well-documented pain. Part of the magic of the song, in fact, is that what it celebrates is not a straight- forward victory. We know from songs like “Black Boys on Mopeds” that Sinéad was not fond of England and had no easy feelings about living there, even as she describes London as a kind of escape from the oppression of home. She had a complicated relationship with her own sexuality, with being sexualized, with relationships with men in general. She said in a 2000 interview that she wished she’d dressed sexier in her twenties, implying that she didn’t quite embody the fantasy that she sings about wanting at the time. Even her dream of making a living through music, a dream she accomplished, was complicated by constant clashes with her record label as they tried to manufacture her into a consumable pop star. These aren’t flaws in the song, or in her life; they’re the whole point. Those complexities are what elevate “Daddy I’m Fine” beyond the class of straightforward girl-power anthems and into something much more nuanced, more interesting, at once both sadder and much more hopeful. It’s a song, simply put, about faith and courage. If life was simple, what would be the use of either?

I’m reminded of a quote by Jacqueline Rose, writing about Marilyn Monroe in her book Women in Dark Times: “I do not find it helpful to present her—or indeed any woman—as either on top of or succumbing to her demons, as though her only options were victory or defeat (a military vocabulary which could not be further from her own).” The song is not a celebration of victory so much as it is a celebration of freedom, a chasmic difference that you can only truly understand once you’ve had to make a choice between the two.

“Daddy I’m Fine” is, of course, a song about fathers, but as with all Sinéad songs, I can’t help but think of my mother when I listen to it. And I can’t think of my mother without thinking of her mother— another woman, like all women in my maternal lineage, whose daughter left her in search of a different life.

My granny was a prototypical Irish Catholic: tough, blunt, honest, seeming to me, at the time, to need no comfort and want no frivolity. I wonder, often, what she would think of the type of woman I grew into—emotional, expressive to a fault, thin-skinned, definitionally frivolous. I sensed her disapproval of me even when I was a teenager; when I wore ripped jeans, when I wouldn’t do the dishes. I loved her, and I know for certain that she loved me intensely, but it often felt like a ritual kind of love, instinctual, rather than a love born of anything we actually had in common. I didn’t think that she understood me, and I don’t think I tried very hard to understand her.

Years after my granny died, though, my mother mentioned offhandedly in conversation that she had denied my grandfather’s marriage proposal three times before finally accepting, even though marriage to a good man, a man that she loved desperately until the day she died, was just about all that a woman could be expected to aspire to in the 1950s. I felt like the air had been knocked out of me, which is how I still feel now whenever I think about her—how little I knew of her, how much there was to understand. I realized with the shame of a child that I’d had it all wrong.

She, too, had an instinctive resistance to the life that had been set out for her; perhaps she, too, had a deep kind of hunger for a different one. And I realized that it didn’t mean anything that my life wouldn’t make sense to my granny; her life probably didn’t make sense to her granny, and that made the two of us infinitely more alike than any minor difference we had about how often I prayed the rosary. Our differences, in fact, are precisely the thing that bring me closest to under- standing her. I’m sure she felt different all the time.

This is the core of the connection I feel to Sinéad: it’s not about technical similarities, biographies, perceptions of self—all that is subject to change, anyway. Rather, she serves as a reminder to me that some lives, even when vastly different in their particularities, have similar shapes, and that certain kinds of women have been carving their lives into inconvenient shapes for as long as anyone can remember—that our challenges and ambitions and desires may not be identical, but that they often have a symmetry, a pattern, a rhyme. The great similarity between us is not found in material details but in a larger arc of our lives, one that bends toward or against the shape we appear to be born into.

My grandmother, my mother, me; a legacy of leaving, of searching for something different than what we were promised or owed, of calling our fathers and assuring them that we’re going to be fine.