Babyteeth Director Shannon Murphy Has Seen Countless Videos of Eliza Scanlen Dancing

Eliza Scanlen in Babyteeth.

A coming-of-age film can be seen as gluey and sentimental; a coming-of-age film about a girl is almost certainly deemed so. But the Australian director Shannon Murphy believes the genre, with its inevitable loss of innocence and doomed teen love, doesn’t have to be melodramatic. Her new film, Babyteeth, is a teen cancer movie that’s more healthily irreverent than it is syrupy. In the film, an adaptation of Rita Kalnejais’s play about a girl diagnosed with cancer, a dying high schooler named Milla (Eliza Scanlen, of Little Women fame) falls in love with a drug addict named Moses who may end up robbing her house at night. In Murphy’s hands—ones equipped with a theater background, a university short film that made it to Cannes, and an obsession with body language—the film is sweet, yet unsentimental enough to let Milla’s first and final love story be a lot less than perfect.

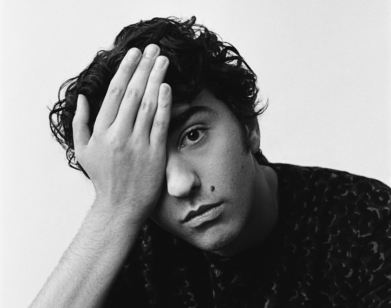

Babyteeth secured a competing spot at Venice Film Festival, beating two sets of odds as a feature debut by a female director. From there, Murphy’s talent for infusing tenderness with a dose of irreverence took her, logically, to Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s female-driven serial killer TV series Killing Eve, for which she directed two episodes. From the Gold Coast, Murphy got on the phone to discuss Milla’s love, Jodie Comer’s laugh, and Scanlen’s dancing.

–––

BESSIE RUBINSTEIN: Hi, Shannon. I wanted to congratulate you for competing at Venice. They definitely don’t make it easy for women.

MURPHY: Oh, thank you!

RUBINSTEIN: Of course. You went on to direct some of Killing Eve. Your episodes, like Babyteeth, are pretty painful, especially for a stylish show. Do you think pain and trauma are the keys to getting at a character?

MURPHY: When you see people at a point of crisis, it’s an interesting way to understand a person—how they react says a lot about who they are, or who they’re trying to become, or who they’re trying to run away from. And so crisis is an incredible intersection in our lives, which of course is high drama, but also which, psychologically, is really complex. It’s a gray area. People can behave in ways that they might usually be ashamed of, or that they might have never tapped into before. So allowing an audience to see that is quite a gift of a moment, if you can make it as authentic as possible. Characters at their wit’s end often display quite a heightened reaction—in some ways a theatrical performance, but when you’re dealing with that kind of intensity, it’s about still making sure it’s grounded and believable.

RUBINSTEIN: The film is adapted from a play; how did you add a frame to what you saw onstage? Coming up with the seaglass-colored palette, for example.

MURPHY: We talked a lot about how we wanted Babyteeth to feel timeless. We looked at a lot of William Eggleston photography, which feels so contemporary still today, but of course isn’t, and that’s something particular to his colors and palettes. For costuming, I follow the energies of the characters, so Milla starts off quite yellow, and then becomes more lavender as she’s connecting more to Moses because that’s more of his color. In terms of framing, we looked a lot at the work of [John] Cassavetes, who I think was really amazing at capturing freneticism. I wanted the characters to have an intimate connection with the cinematographer, Andrew Commis, and created some choreography that would make that energy happen.

RUBINSTEIN: Movement in general seems important to you; you did a miniseries about an Iraqi-Australian boxer.

MURPHY: Yeah, my work, even in the theater world, was always considered really physical. And that’s sometimes the thing that gets lost. Theater, as you’ve pointed out so well, is a wide shot. With cinema, though, there’s a disconnect between the actors and their bodies. As someone who used to love dancing, and love watching choreography, the physicality of those characters is just as important as the words they’re saying. If you took all the words out of Babyteeth, you could still understand almost everything that’s happening. With Milla, Eliza [Scanlen] and I had to find how she moved and danced, so Eliza would dance every day. She’d send me a different daily video from her bedroom.

RUBINSTEIN: I’m jealous. Thinking about nonverbal communication, I picture Milla and Moses at the pool, just kind of bouncing together to the same song, but really connecting. Their relationship is interesting because it isn’t always overtly romantic in the way that we’re used to; sometimes it just feels more like mutual need. But maybe that’s love in its purest form.

MURPHY: That’s a beautiful way to express it, actually. I think, almost subconsciously, that when Milla meets Moses, she knows that if things got really hard for her, she could ask him to do something that she couldn’t ask anyone else. And she sees an opportunity to live in a way that she hasn’t yet. In turn, Moses is literally breaking into her family because he’s running away from his own, and she never judges or even really asks about his drug abuse. With her, he doesn’t have to explain himself. You’re right. It’s about mutual need. And that’s what love is really about, because at the end of the day, we can fall in love with anyone. It’s a decision that you make. And that’s where the payoff is, really.

RUBINSTEIN: Sounds like maybe having nothing left to lose is the best way to fall in love?

MURPHY: I think so.

RUBINSTEIN: How did you and Eliza work together to make sure that these ideas didn’t get sappy?

MURPHY: I’m not sentimental. I think that’s what drew our actors to the work. They believed that the story felt more authentic for their age group, because it wasn’t undermining anything with soppiness or cheesiness. And Milla gets a lot of agency…she’s really intelligent. She’s driving the decisions in her life. When people get too emotional I love to have a bit of a crazy take. Like in Killing Eve, when everyone is watching that landing on the moon. I did one last take and I said to Jodie [Comer], just do anything you want, forget about my directions, forget about your ideas, just go for it. And she did that crazy laugh, which now is in every trailer.

RUBINSTEIN: So irreverence is the key.

MURPHY: Yeah, because people don’t talk in sentimental ways a lot. We have coping mechanisms that stop us from doing that. Also, the younger generations are really upfront and honest and tuned in and I wanted to make sure we caught that and gave young people some credit. Because young adult stories often push you to have big, emotional feelings. And I want that too, but I want you to be able to intellectualize the story rather than being so manipulated. It’s that thing where you hear a piece of music and it doesn’t matter what the context is, it’s going to make you cry. I don’t like to work that way.

RUBINSTEIN: Because then you’re not really involved? You’re just, maybe, using the song or movie as a way to feel something?

MURPHY: Exactly. It’s cheating.

RUBINSTEIN: That brings me to the head-shaving scene, because I think that’s a scene that could easily become overly dramatic or symbolic.

MURPHY: To be honest, there was no way that could be a dramatic scene because we were actually letting Toby [Wallace] shave Eliza’s hair, and he’d never done it before. Rrather than make it this really scared, traumatizing moment for Milla…no, she wants to become a punk in that moment.

RUBINSTEIN: What about this film makes it particularly Australian? Besides…being set in Australia.

MURPHY: Our goal was to make it feel really Australian without any actual shots of iconic places in Sydney. A lot happened in the post-production sound world. We have some crazy bird noises and insect noises in the summer in Australia, just going bananas. So we really pushed that and made it feel like sitting in that Australian summer with the sound.

RUBINSTEIN: How do you make those moments feel like they’re memories?

MURPHY: Thank you for noticing that. We talked all the time about how certain scenes are like Milla from the dead, looking back on this time. I loved that in Rita’s play, it would say what the dead said to Milla. They’d say, like, “Dance, dance, dance,” or, “Feel the sun on your skin.” I have a bit of an obsession with last moments because a family member threw out a whole bunch of photos of my grandmother when I was in my early twenties, and it shocked me that anyone would do that. But how do you honor last moments with all the feelings that are involved?

RUBINSTEIN: Do you believe in the redeeming power of romantic love?

MURPHY: I do. I really do. Both Rita and I are romantics. Love can heal you during a time of crisis; Milla is having the greatest existential crisis you can possibly have. Humans really crave an intimacy that feels special and unique to just them. And I think people can transform your lives with love. Even if it’s short lived.