Rosalie Varda on the Enduring Legacy of Her Mother, Agnès

Earlier this year, cinema lost one of its brightest lights with the passing of Agnès Varda, the boundless pioneer of the French New Wave and documentary filmmaking. For a while, it seemed like her 2017 film, Faces Places, a whimsical and emotional collaborative effort with the street artist known as JR, might be her last. That turned out to not be the case. In her posthumous final film, Varda by Agnès, she invites viewers to take one last look at her vast and storied artistic career. The film pieces together scenes from her films and moments from various “masterclass” talks to put Agnès in conversation, one last time, with her audience. Interview sat down with Varda’s daughter, Rosalie Varda, a former costume designer who won an Oscar for producing Faces Places, and who produced Varda by Agnès, to discuss growing up with artists, the Martin Scorsese superhero controversy, and what made her mother a singular beacon of creativity.

———

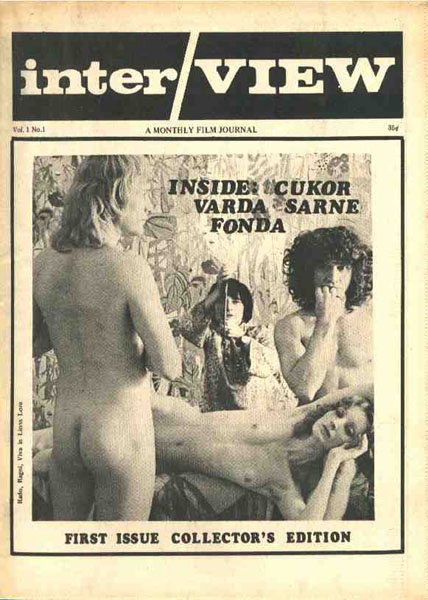

CONOR WILLIAMS: Your mom, Agnès, was the first cover star of Interview back in 1969. She was also on the cover last year, so it’s really great to be talking to you and keeping the Varda legacy alive here. So this new film, Varda by Agnès…

ROSALIE VARDA: Did you see it?

WILLIAMS: I saw it at the New York Film Festival and I really liked it. It’s a good introduction for new fans, but it’s also a nice bit of closure for people who were following her work for a long time. How does it feel to have the film finished? Is it kind of bittersweet?

VARDA: Well, maybe bittersweet is a good way to say that. It’s a project we started in 2015. I was traveling a lot with her when she was doing those masterclasses, and each time I would hear her, and I would think, “Wow, it’s so interesting what she’s saying, and each time it’s different.” So in 2015, I told her, “We should do something about this. We should do some kind of a documentary because one day you won’t be able to travel anymore.” And she said, ‘Oh, you think it’s interesting, talking about my life?’ I said, “Yes. I think it is, and it’s true, you won’t be able to do it, so we should do something.” So we started that project.

Photo courtesy Mk2 and Janus Films.

And then we stopped because I had the idea to call JR, the artist, and we did Faces Places. And so we took back the project in 2018. Suddenly, she was interested to share. She thought, ‘Well, you’re right. Because in fact, my life, has been a body of work. I have been through…technology.’ She started with a darkroom and finished with the iPhone. She said, ‘Maybe for the younger generation, they don’t even know what is the darkroom.’

WILLIAMS: You also produced some of her films, like Faces Places.

Varda on the cover of the very first issue of Interview Magazine in 1969.

VARDA: Yes. And I helped on the production in the company, which is my mother, my brother, Mathieu Demy, film director and actor, and me. And we always worked on the body of work of Jacques Demy. I mean, all his films. We restored and digitized Jacques Demy’s films and we restored and digitized all of Agnès’ films. And now we’re working on this catalogue. We do work a lot with Janus and Criterion.

WILLIAMS: You’ve also had a long career as a costume designer. What drew you to that work?

VARDA: I was in an art and cinema family and as a little girl, I loved to dress up. I really wanted to be a costume designer around 14. Looking at the film of Jean Renoir called Le Carrosse D’or, there’s one scene where you have Anna Magnani wearing a dress that is inspired by Veronese, the painter. It’s in taffeta, like brownish-green, and I thought, looking at that, that this is what I want to do. So after school, I did art studies and fashion studies. I worked with my mother on Vagabond. I worked with my father, Jacques Demy, on several films, and I worked in theater, in opera halls, in dance, I mixed everything.

WILLIAMS: What are the films or television series that you’ve been watching?

VARDA: To be honest with you, I don’t look too much at TV series. I don’t have time. But I really like the film Joker. I think it’s very interesting, on the subject, ‘What is madness?’ What is the border? While your madness is on the edge and how it’s a little bit structured to stay in your life, and yet you manage your life. I saw The Irishman. I loved the film. I found it very sad, very melancholic.

Agnès Varda. Photo courtesy Ciné-Tamaris.

WILLIAMS: It wasn’t glamorous.

VARDA: And the actors are just insane. So good. And the things that really touched me is that watching the film, I realized that I didn’t know anymore what age the actors were in real life. I let myself into it and thought, “I accept the concept that the machine is going to change them.” What is important is the emotion you have. I found it very personal. I don’t know the life of Martin Scorsese, but I feel he put a lot of himself into it. This is cinema. When you look at a film like that, there’s no doubt about cinema. I know there’s a polemic now, what [Scorsese] said about Marvel films. He did it in a conversation, and if you take it out of the conversation, it suddenly creates a fuss. I don’t understand the polemic. I think it’s two different worlds. It’s like if you’re comparing literature, fiction and comic books. Diversity is only what matters. People are able to choose to go and see the films. They’re not obliged. The diversity is the rich thing of the culture. We have to say this.

WILLIAMS: In Varda by Agnès, towards the end, there’s a kind of installation or a sculpture of sorts called a Cine-Shack. Houses made of celluloid film and canisters and things like that. Growing up with your parents, did it kind of feel like you were living in a Cine-Shack a little bit?

VARDA: [Agnès] began on The Gleaners and I recycling things. And fact of the shacks is that now you have digital files from films, then what is happening to those beautiful 35 millimeter prints? I kept the prints, I pay for storage where I kept, like, 40 prints. Usually the producers, they just trash them. And I thought to myself, in 20 years, maybe we would be very happy to have those prints. We did an educational program with kids, giving them a piece of 35mm. They were looking at that like it was the Middle Ages. My childhood was in cinema, and having that luxury to be with artists. I didn’t know anything else. This was normal for me to meet people. To have Antonioni, going to spend a weekend in his house. It was normal for me to be on holiday with François Truffaut. Today, I look at that, and I say, “Wow!” But when I was a child, it’s just like, “Oh, it’s a guy, like everybody, but he’s weird, because he goes on the beach with his suit and his shoes.”

WILLIAMS: Agnès has inspired so many people to follow the dream of cinema. I’m also a filmmaker, and I have to tell you that the most recent film that I made was a film about my experiences with grief. I called it Water’s Edge, as a reference to something that Agnès says in her film Ulysse: ‘If you watch the water’s edge, time fails to remain the same.’ And I kind of felt that in making the film. Like I was recreating memories in real time and then also putting down a document of a life and grieving and making this film.

VARDA: How long is the film?

WILLIAMS: The film itself is about half an hour, but I was working on it for a couple of months. And you feel that experience, of time moving back and forth like the tide when you’re making something like that. Is that what it felt like to look at Varda by Agnès, a little bit?

VARDA: I understand your question, because of going back into the films and the archive, but I didn’t feel that way. I felt more in the future. We are more trying to say, “What is an image? What is a still image? What is a moving image? What is out of the frame?” Trying to put the audience in the confrontation of thinking, “What is the image you have in front of you?” Of course we go back in the archive, as you say, like the waterfront, the seagulls come to the sand, and go back to the sea, and go back to the sand. And I cannot talk for her, so it’s difficult for me. I can help to understand, to give clues, but it’s difficult for me sometimes, to find a good position between working with her, being her daughter, being her producer, and taking care of the company.

WILLIAMS: It blends together.

VARDA: It blends together.

WILLIAMS: It seems like beaches had always kind of been this site of introspection for her, a sanctuary in a way. Her happy place. What was your happy place?

VARDA: I don’t know. I think all her life, she had been next to beaches in one way or another. During the war, she was in Sète, so she went to the beaches. Then, with Jacques, they bought a property next to the beach, and then she was raised in Belgium where she used to go the beach. It’s magic. She gives some answers in The Beaches of Agnès on that question, but for me, the beaches are just like magic. To have the sea coming and going back. The sand, the horizon, it’s always changing. It’s like a film.

WILLIAMS: I don’t love the beach, but I do live next to the beach and it is very cinematic. Just to sit and watch the sky.

VARDA: You don’t like the beach, you like the mountains?

WILLIAMS: Yeah. Forests and things like that.

VARDA: You don’t like swimming, you don’t like the water?

WILLIAMS: No. But visually, yes.

VARDA: I think Agnès loved the water. I think she was more related to the water and the beach than to the forest and the mountains.

Photo courtesy Mk2 and Janus Films.

WILLIAMS: In the film, she lists these three words that are important to her: ‘inspiration, creation and sharing.’ What did those mean in your relationship together?

VARDA: Sharing 60 years of life together. She’s an inspiration. She was difficult, tough, maybe strong, maybe hard sometimes, but you don’t do that load of work, if you are not strong. She gave to my brother and me the curiosity of being alive, of looking. Like you are in front of me, and you have that guy behind you, cleaning the windows. It’s cinematic. It’s like in a film. Creation, I think it can be everywhere. Everyday. Creation is not only being an artist, it’s being able to have that imagination open. What do you think?

WILLIAMS: There’s creation everywhere.

VARDA: Yes. Some people, they don’t see anything. Even in a coffee shop, there’s things that are interesting to look at. They don’t see where they are. If you tell them, ‘Did you look at the ceiling? Did you see that design? Did you look at the lamp? Did you look at the people there?’ If I had to say one word about Agnès, I would say ‘curiosity.’ In everything. Creation is not without sharing and creativity is not without inspiration. Inspiration is everything. And it can be in paintings, in sculpture, in everyday life. The sky, the people, the sidewalk. She was somebody who was totally in the present. Scorsese said something about her that I really liked. He said she was free. She had liberty.

You know, Agnès met Andy Warhol in the sixties and he loved Agnès, because I suppose Agnès was a little bit different. They were not close friends, but they had a lot of respect for each other. Each time she would come to New York, she would go to the Factory and see each other, and speak about cinema. How did you do your film, in digital?

WILLIAMS: I shot it on 16mm. And then digitized it.

VARDA: Oh. You are a little bit a…nerd.

WILLIAMS: [Laughter] Yeah. A little bit.

VARDA: A hipster nerd.

WILLIAMS: But that’s all thanks to your mom.

VARDA: [Laughter]

Varda by Agnès comes to theaters on November 22nd.