Remembering Philip Seymour Hoffman

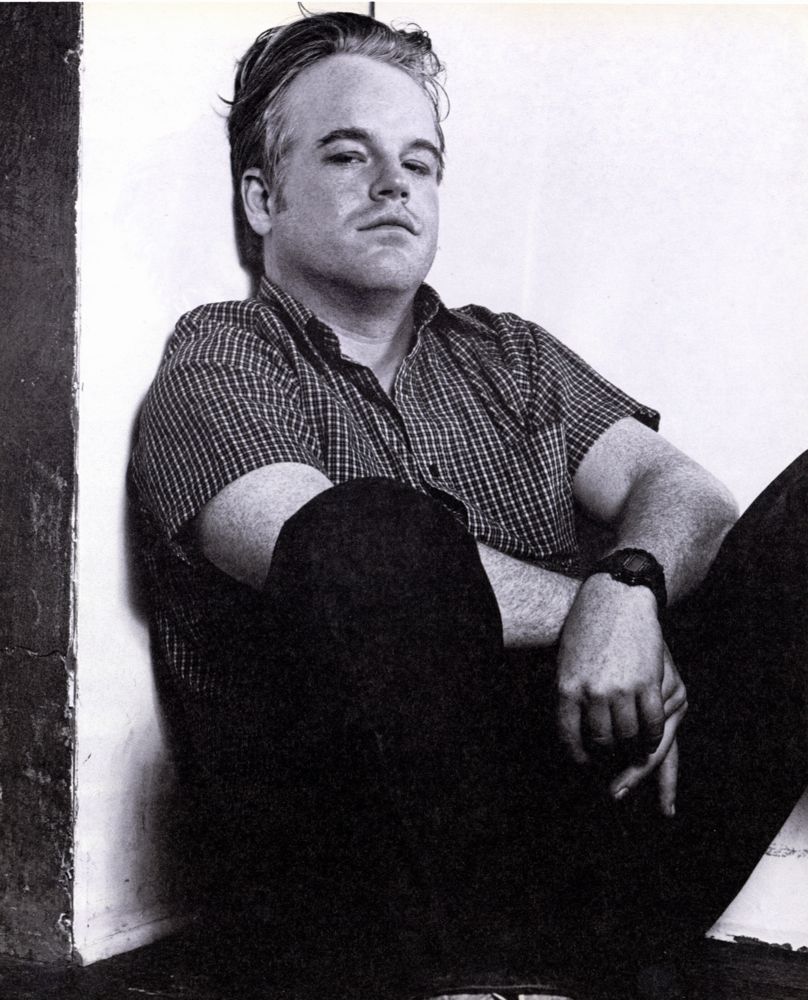

ABOVE: PHILIP SEYMOUR HOFFMAN PHOTOGRAPHED BY STEVEN KLEIN FOR INTERVIEW’S FEBRUARY 1999 ISSUE.

Philip Seymour Hoffman didn’t burst onto the scene overnight. Since his first few significant parts in the mid-’90s, it seemed like Hoffman had always been there. He was never an ingénue, but an acting stalwart with years of experience whom you could always count upon to invigorate the show.

In reality, however, Philip Seymour Hoffman was much younger than the wisdom of his performances suggested. When he passed away this weekend, the actor was just 46, a father of three young children. That the world has lost a hugely talented and magnetic actor is indisputable. We first met Hoffman in February of 1999. He had yet to be nominated for an Academy Award—as he would be four times between 2006 and 2013—but with roles in Boogie Nights, The Big Lebowski, and Happiness, he was long established in the eyes of Interview. He was confident and unflappable—unafraid to tackle the questions of sexuality, masculinity, and gender norms posed to him by our interviewer Patrick Giles.

Philip Seymour Hoffman

By Patrick Giles

Philip Seymour Hoffman has a remarkable face. One look at it and you know that, contrary to rumor, movies haven’t lost their genius for discovering actors who are capable of being themselves while occupying the spirit of another person and mirroring the secrets and desires of everyone watching in the dark. Hoffman’s not your stereotypically Hollywood-handsome face; you need to live with it to discover its magic. It dates back to an era when male movie stars didn’t all have to look like Brads or Matts. It’s a face enough like our own faces to be recognizable, yet so vividly unique you can’t take your eyes off it.

In the past, James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, and even John Wayne helped men confront who they were and why they were. The thirty-one-year-old Hoffman, on the brink of a major career, shares that quality, but in an era when manhood itself is under the gun. His character’s sudden desperate kiss with the porn star played by Mark Wahlberg in Boogie Nights (1997) is one of those great but terrible screen moments when love and reality collide. Hoffman’s lonely, mortifying performance in Happiness (1998), meanwhile, was the key to that harrowing study of alienation and irresolvable needs. Onscreen, Hoffman is the prototypical ’90s male: questioning, even baffled, but determined to get to the bottom of himself by any means necessary.

PATRICK GILES: Let’s begin with the scene where you kissed Mark Wahlberg in Boogie Nights. A friend of mind said after seeing that, “Boy, if I had Phil Hoffman’s role, I would have messed up as many takes as possible!”

PHILIP SEYMOUR HOFFMAN: [laughs] That scene couldn’t have been more natural. When we came to do it, Paul [Thomas Anderson, writer-director of Boogie Nights] said to Mark, “Don’t reject him on the first two takes,” but he didn’t tell me. So at first Mark was coming at me and it was very wild because the thought of my character, Scotty J., getting what he wanted was much scarier than being rejected. It’s like, when you get what you want, what are you going to do with it? In the end, Paul was more interested in finding the sadness in Scotty. Anyway, Mark and I kissed a lot that evening.

GILES: Now Scotty seemed to me to be hesitant about his sexuality but the character you play in Flawless, the upcoming Joel Schumacher film, is gay and a “pre-op” transsexual, right?

HOFFMAN: Yes. Rusty’s this guy who works as a seamstress and he’s also a drag performer who coaches the other queens who sing at this club. He dreams of becoming a woman, but he’s not on hormones or anything. He’s not totally comfortable with the term drag queen because he doesn’t think it applies to him. His ultimate goal is to be married to a straight man.

GILES: To be Donna Reed or something.

HOFFMAN: Exactly. To make dinner and have adopted children that he makes lunch for and sends off to school—what he himself obviously didn’t have growing up. He wants to be accepted within some type of normality and, in his secret heart, it’s the straight world he considers normal.

GILES: What happens to him?

HOFFMAN: He hooks up with a heterosexual man, played by Robert De Niro, who lives in his building. Bob’s character has a stroke and his doctor says he needs to start taking voice therapy, but he’s too scared to leave the building, so he comes to me for voice lessons and is force to deal with who I am. Bob’s character is somebody who’s very proud of being a man, having a good body, hanging with his straight friends and drinking beer, watching the game. Anything that’s outside of that is very threatening to him, so his sense of I-can-kick-your-ass machismo is met head-on by this guy who thinks he’s a woman. In a way, it’s a kind of love story, although they barely touch each other and I wouldn’t say they even become great friends. By the end, though, you see that they have respect for each other and have found more similarities than differences between them.

GILES: Interview is dedicating this whole issue to the evolution of masculinity in the last thirty years. It sounds like you might have gone into that subject a lot doing this movie.

HOFFMAN: Yes, I did. I think men struggles with their masculinity more in today’s culture than they have done in the past. I can’t speak for the rest of my generation, but I know that for me, growing up, the question “What does it mean to be a man?” was very sketchy. Flawless does approach those issues because you’re dealing with one guy who has lost his sense of masculinity and another guy who doesn’t think he ever had it.

GILES: How did you play someone who never felt masculine?

HOFFMAN: It seems to me that guys like the one I play go out of their way to try to be feminine, so I had to work on the fact that their physical behavior and vocal behavior is all very intentional and becomes a part of them. That’s different from the average effeminate man you might meet on the street. So I approached it by asking myself, What is it like to be something you’re not.

GILES: Were there moments when you thought, I am totally at sea and don’t understand this at all?

HOFFMAN: I always knew where I needed to go but I sometimes had a problem getting there, so I had to work harder at it. Once in a while I’d wanna take off the blouse and heels because I’d get that “I just wanna be a guy” feeling I had when growing up. But what is that? Does that mean my legs aren’t crossed? Does that mean I sit with a little slouch, my elbows are on my knees, and I lower my voice? Now am I a guy? Now do you accept me as a guy guy? It was weird.

GILES: I think every man, whatever his sexual persuasion, should be required at one time in his life to go out into the world wearing high heels and makeup. He’d learn a great deal.

HOFFMAN: [laughs] I did. You should of heard all the comments I got the minute I put on lipstick. All the drag queens went, “Ooh, you look great.” When I’m not in drag, no one ever goes, “Oh, Phil, look at that shirt on you.”

GILES: Really?

HOFFMAN: Never. It made me realize that women are the life force we look at for their beauty.

GILES: So what beauty secrets did you learn on Flawless that you can share with our readers, especially us full-figured types?

HOFFMAN: [laughs] I learned that very loose-fitting, low-hanging blouses look wonderful. And if they’re very light and sheer and if you wear them with black pants and black loafers, that’s very nice. But plastic sandal heels are a no-go. They just cut up your toes.

GILES: I assume you’re heterosexual.

HOFFMAN: Yeah, I am.

GILES: I figured.

HOFFMAN: [laughs] It’s the slouch.

GILES: Men have changed so much in our time—or, at least, perceptions about how they’re supposed to behave have changed. Do you think those changes had an effect on you growing up?

HOFFMAN: My mother’s a staunch feminist, so I grew up with very strong feminist messages. As a result, I battled her in my teenage years because my image of being a man was a deformed one.

GILES: Men were male chauvinist pigs?

HOFFMAN: Right. I was a breed of people who aren’t capable of doing anything, really. At college I began to get the idea that being macho wasn’t the accepted norm in the liberal world, and especially the world I entered into, which was the artistic world. I had a lot of problems with that because I was struggling with the need to be proud of being a man, which wasn’t something I was feeling.

GILES: Men seem to be going through an identity crisis, the way women were around 1969. Do you agree with that?

HOFFMAN: Totally. The men I know are either getting smashed, watching football, and trying to get every last piece of tail in the world—fucking around their girlfriends and denying themselves intimacy and the chance to make a connection—or they’re just puritans. These are the kinds of guys you just want to shake and go, “C’mon! Get up. Stand up for yourself. You’re sinking the couch.”

GILES: Are men going forwards or backwards?

HOFFMAN: I’ve been reading a bunch of stuff lately—like Joseph Campbell—that has made me realize that people in our cultural, especially in the liberal community, often go in search of a foe. It’s like we always need a hill to climb up or something to push against, or we feel as if we’re not working constructively in the world. I know I’m like that, and I know my mother’s like that. We rarely say, “Hey, things got kind of better didn’t they?” Or “Wow, this is good stuff I’ve just seen lately.” And if we do, the community just starts griping and becomes cynical again. That’s okay because it keeps us on our toes. But we shouldn’t underestimate what has been achieved.

GILES: Would you like to do a straight romantic role?

HOFFMAN: It’s something I would love to do and I hope I get the chance. But to tell you the truth, there have been parts like that I’ve wanted very badly in my career and didn’t get because I think a lot of them go to—and I’m not putting myself down here —better-looking guys per se in the film world.

GILES: I think you’ve got a great face, and when other people see the pictures of you in this issue, others are going to agree.

HOFFMAN: Frankly, I get much more sensitive about what’s written about me than how I look in a photo. I’m so used to people seeing my image in plays and films that what they think about how I look is none of my business. If they says, “Hey, he doesn’t look good,” I’m like, Whatever, because I know I look different from day to day. But if you’re up there putting your heart into something and people reject your performance, that’s very painful. The written word can kick your ass.

THIS INTERVIEW INTIALLY APPEARED IN THE FEBRUARY 1999 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.