nyff

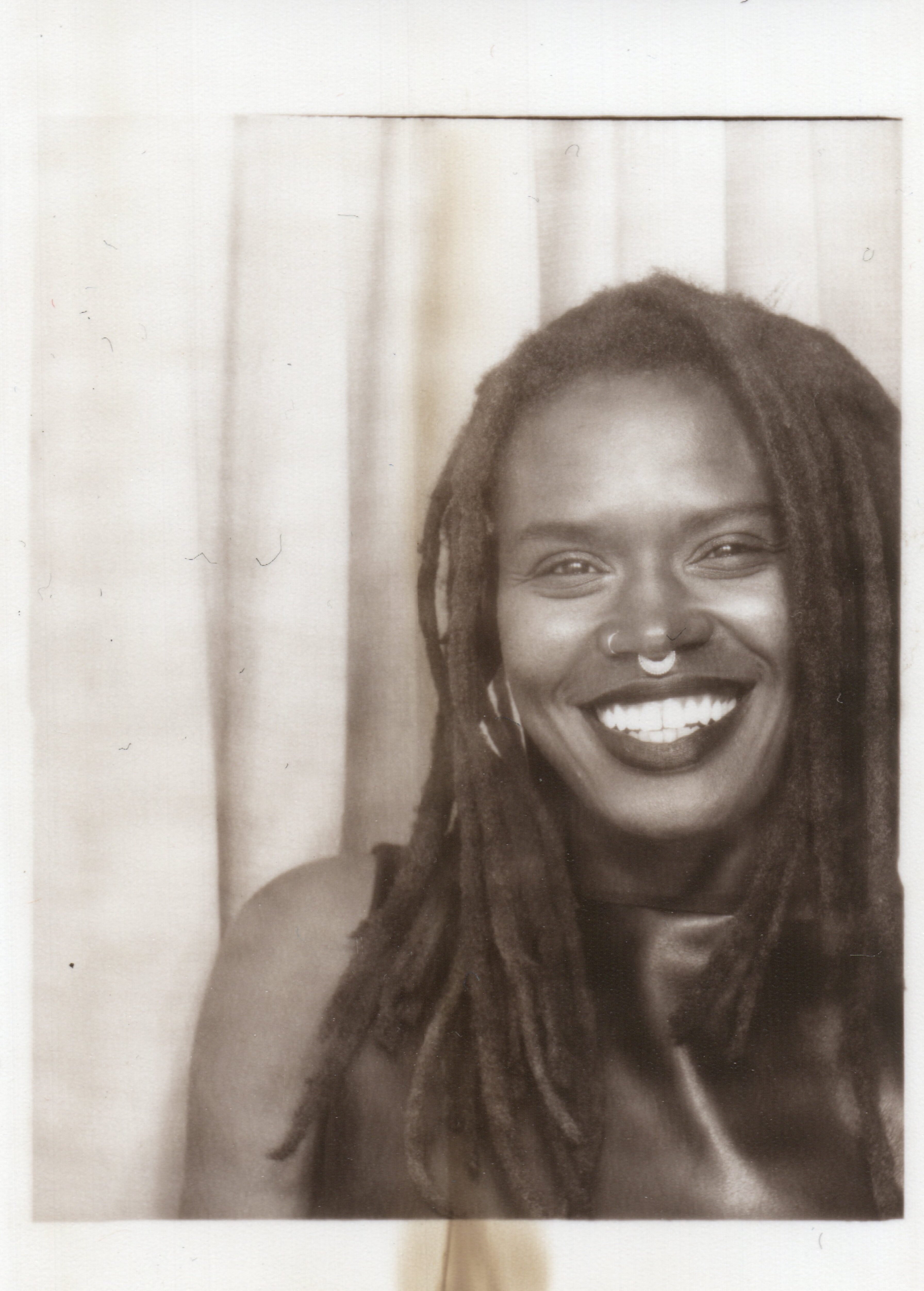

Raven Jackson Gets Her Hands Dirty in Her Debut Feature

Raven Jackson is taking it nice and slow. Her debut feature, All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt, premiered at Sundance earlier this year to rave reviews for its lyrical, drawn-out sequences. The film is like a pastiche of memories, arranged not by chronology but by instinct. It’s a sparsely dialogued love story set in ‘70s Mississippi between protagonist Mack and her family, best friend Josie, and lost lover Wood, spanning decades and generations. And from the squishy mud between Mack’s fingers to the vibrations in her chest while watching a home burn, it’s the sensory details that make All Dirt Roads so profound. The day after her film screened at New York Film Festival, we met up with Jackson to better understand the making of this exploration of Black rural life, from creating rich sound to wrangling snakes.

———

RAVEN JACKSON: Hi, I’m Raven. Nice to meet you.

MEKALA RAJAGOPAL: So great to meet you. It was beautiful to watch All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt on the big screen yesterday. It’s actually my first time attending New York Film Festival. And this is your first feature-length film. How does it feel to be premiering first at Sundance, and now here?

JACKSON: Even though we premiered earlier this year, it feels very special to be bringing it to New York Film Festival. It almost feels like another premiere, in a way. I used to go to school here, so I would go to New York Film Festival often, and it feels so special to be having All Dirt Roads play at Alice Tully Hall. I really took in that moment yesterday. It’s really special. It’s a dream.

RAJAGOPAL: You’ve directed short films in the past, and you’re also a photographer and a poet. Do you want to speak to how your other practices informed this work?

JACKSON: Yeah. In an organic way, I really leaned on photographs to land me on the soil of film. And my poetry, even before I knew I was going to be a filmmaker, circled nature, the body, and some obsessions I’ve had before then. So whatever medium I’m working in, they all speak to each other and inform each other. It’s been very helpful for my photographs to inspire what I write.

RAJAGOPAL: The film is very poetic. Like, it was clear that a poet wrote this, and one of the things that made it captivating despite the lack of dialogue was how sensory it was. Like the scene where Mack was playing in the clay in the water; I could feel it in my hands.

JACKSON: Thank you. I just revere and love hands. I recognize the power of eyes but, for me, hands are right up there, so I always knew there would be a lot of detail shots of hands. The film deals a lot with what’s passed from one generation of family to the next with care, with holding each other, with love, and I wanted the hands to demonstrate that. And in a film that doesn’t rely on a lot of dialogue, I am looking to the body to speak.

RAJAGOPAL: I think my favorite sense to experience, though, was sound. It was so sonically rich, with the crickets and rainstorms, and it was interesting that while there wasn’t a lot of music, it was like those sounds were the music soundtracking the film.

JACKSON: I love that you say that because that’s what the intention was in a film that doesn’t have a lot of songs, to allow the sound design to be the score. If the film’s going to be so quiet, it’s asking for a very experiential, evocative level of sound design to hopefully open another doorway into the interiority of the characters. So yes, it was very intentional. It’s a quiet film, it doesn’t have a lot of dialogue, but we enhanced the sound to really allow the quiet to say something and let the nature and the rain be present.

RAJAGOPAL: And another kind of sensory thing is the scene showing the tradition that the title is referring to. How were you first introduced to eating the clay dirt?

JACKSON: My mom had told me about it a while ago, but it was when I had a conversation with my grandma about the practice of eating clay dirt that it really stayed with me. I ended up titling a poem [after it] that actually has nothing to do with the film. But I was interested in bringing that thread into the film after more conversations with my family because it really speaks to Black women in particular who are so close to the earth, as this film’s characters are. Black women are the ones who mostly practiced the eating of clay dirt in the rural south. And it’s not just any dirt, it’s very specific banks. It’s after rain when the earth smells so rich. With the water connections to the film, it made complete sense.

RAJAGOPAL: Right.

JACKSON: But it was a thread that was very important for me to do in a way that wasn’t sensationalized at all. It was important to cast people who are familiar with it. Grandma Betty in the film, Sheila Atim, is familiar with it. It was very important to me for it to feel authentic and to get it right by talking to people in my family, like the brown paper bag in the cabinet. It’s a small thread, but an important one.

RAJAGOPAL: How did you land upon this cast? There’s a first-time actor as well, right?

JACKSON: Yeah, several. I like to work with a mix of more experienced actors and first timers. Charleen [McClure], who plays late teens through early thirties Mack, is a friend in my life. And she’s a poet. One day, I just saw it. I needed someone for this role whose face carries many years believably. But she’s also someone whose face says a lot without needing to say words, which is something the role needs. And when looking for a younger version of her, we discovered Kaylee Nicole Johnson, and the eyes had a resonance between Kaylee and Charleen, but the emotional maturity of Kaylee also really came across. For Reginald Helms Jr., who plays the older version of Wood, I was researching in the production office and I typed in, “Musicians from the South,” and when I saw one of his videos and how expressive he is with his body, I wanted to meet. It just happened that someone who was working on the film had a connection to one of his managers. It was a lot of trusting what moved me and seeing what came from that. And also, of course, seeing the chemistry between people. The cast is amazing and I’m so grateful to have worked with each one of them.

RAJAGOPAL: I love that it all fell into place like that. Obviously, you also play with time a lot, and the scenes are arranged, not chronologically, but more emotionally and instinctively. How did you decide in what order to put together all of these different parts of the story?

JACKSON: I knew it was such a modular script that after I shot it, the film wouldn’t look exactly like the script. So after I had the footage, I worked with Lee Chatametikool, an amazing editor, and it was a lot of finding and tracking the emotional journey. Having index cards on the wall, taking some down, putting some up. And knowing when you need a certain emotional beat or when you need some forward movement or some quiet. Just really listening and finding.

RAJAGOPAL: It almost feels like a film that you can’t plan or storyboard.

JACKSON: Yeah, totally. You have to be open to the process, and sometimes not knowing and just needing to sit with it. There was a lot of sitting with it and taking days away to re-watch and rest your eyes.

RAJAGOPAL: You were talking about how you learned about the namesake tradition from your family. Is there a connection between this depiction of Black rural life and your own roots?

JACKSON: Yeah. It’s a fiction film, but it’s in the details. I grew up in Tennessee and my mom’s from Mississippi where we shot the film. I grew up fishing. I was taught how to skin a fish. There are photographs from some of my family albums on some of the walls of the scenes.

RAJAGOPAL: Oh wow.

JACKSON: So it’s a fiction film, but in the details, that’s where some of my truths lie.

RAJAGOPAL: With that in mind, I’m also curious about what your references looked like.

JACKSON: I did a pitch deck for the film before I wrote a page of the script, and I needed to do that to really land myself in what the film is. I needed to be able to smell the air before coming to the page. It was a lot of photographs I took, and some Super 8 footage of the South and of some family members. The sensuality of the scent of green papaya was a reference. The sound design of Silent Light. Tchaikovsky’s Mirror was referenced. And I thought a lot about the poetry of Lucille Clifton.

RAJAGOPAL: It comes through that you used all these sensory ideas instead of just the visual and sonic. Do you have any stories from shooting in Mississippi?

JACKSON: For the grocery store scene with Mac and Wood, the longer hug, the scene was written to have a deer in the scene at some point, and they see the deer rummaging through trash. And when we couldn’t get the deer, at first, I was like, “Oh my gosh, we need the deer.” Sometimes something doesn’t work out, it’s a gift when it falls through, because the scene didn’t need the deer. It just needed Mack and Wood with each other, and eventually hugging each other. This is a very elemental film. It wants the essentials, and there were several moments where I was reminded of that.

RAJAGOPAL: I did notice the coordinated animal moments. How was it to work with an animal wrangler?

JACKSON: I mean, we were in Mississippi, and so there are a lot of animals. Dale Bell, Derrick Scott, and Jamie McIntosh were the animal wranglers we worked with. It was nice to have someone who could do sweeps for snakes, or look in the water. You never know. I didn’t realize how dangerous Mississippi waters can be until I was trying to shoot.

RAJAGOPAL: Are there crocodiles out there?

JACKSON: Yeah, and the snakes and stuff. But it was good working with him. He found out he knew my mom from high school.

RAJAGOPAL: That’s cute. Do you have any plans for another full-length film?

JACKSON: Yeah, I do. I know what it is. I’m not saying too much about it yet, but as this film is coming into the world, I’m excited to start to build something else.