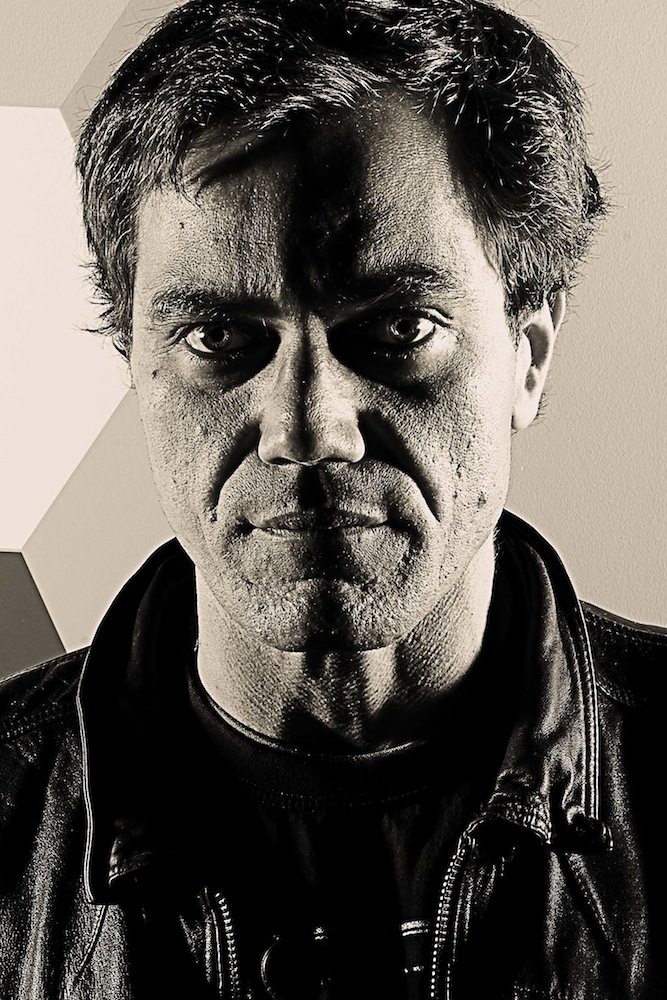

Ramin Bahrani, Michael Shannon, and the 99.9 Percent

ABOVE: RAMIN BAHRANI (LEFT) AND MICHAEL SHANNON AT THE SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL. PHOTOS BY KATIE FISCHER.

99 Homes, the new film from writer-director Ramin Bahrani, begins with a single, three-minute shot. About to be evicted, a man has just killed himself in the bathroom of his Florida family home. It’s an intimate setting: toothbrushes on the counter, a stocked medicine cabinet, and blood. The first time the camera cuts, it’s to a sealed body bag loading into the back of an ambulance. After a screening of the film at the Sundance Film Festival, Bahrani explained that he wanted the audience “to feel the weight of the death.”

Starring Michael Shannon, Andrew Garfield, and Laura Dern, 99 Homes is a thriller about Florida in the throes of the housing crisis. Garfield and Dern play Dennis and Lynn Nash, a son and mother forced out of their family home. Shannon is their evictor, Rick Carver, a man with a new car, more McMansions than mistresses, and a gun concealed in an ankle holster. While Rick does his best to value practicality over sentimentality, he sees something in the distraught Dennis and offers him a job. To work for Rick is to work for the enemy, and to survive.

RAMIN BAHRANI: Did you know Michael is in a rock-‘n’-roll band?

EMMA BROWN: I did.

BAHRANI: It’s pretty cool, have you ever heard him play?

BROWN: No.

BAHRANI: I have heard him three times I think now. He’s pretty damn good.

MICHAEL SHANNON: That’s the side that I want people to know about me—the rock-‘n’-roll side. I might actually retire from acting and just do music.

BAHRANI: And my films.

BROWN: I think you have too many directors that you’re committed to for you to retire from acting.

SHANNON: Yeah Ramin, Jeff [Nichols], Liza Johnson…

BAHRANI: For this new thing I’m writing now, every time Michael’s character comes in the script I put Talking Heads on.

SHANNON: That’s my favorite band, Talking Heads.

BROWN: Ramin, you said that as soon as you got down to Florida to research 99 Homes, you realized it was going to be a thriller. What kind of movie did you think it was going to be before that?

BAHRANI: I didn’t know exactly what it would be but I assumed it was going to be a social drama. I thought it would be really good. Then when I got down to Florida, a couple of things happened. One was, immediately the structure hit me—quite quickly actually—this deal with the devil film. The guy who gets kicked out of his home, starts to work for the very man who kicked him out, and then he himself gets to the point of evicting people. That seemed like enough for a movie. The more research I did and the more I spent time there, the more I realized that there’s actually some other thing going on, which is guns, violence, deep corruption, thievery, gaming the system, and cons. There was something visceral and frightening about it. I remember when I showed photographs of the real-estate broker to someone and they saw the gun on his ankle, they were like, “Is it a detective?” These were some of the responses I would get early on. I was like, Wow, this could have the gangster element of a guy training this young lad into the seduction of crime. Personally, I liked it as a creative challenge—to do something I hadn’t done. I’ve been trying to continue to push myself into things that I don’t quite know and I’ve never done before. I wanted to push myself creatively as a filmmaker. I thought it could also be new for an audience—when was the last time you saw a humanist thriller or a social thriller?

BROWN: When Rick takes Dennis on as his protégé, is he looking for a way out? Dennis is obviously really clever, and I can see how that would be attractive to Rick, but he is also so obviously empathetic.

SHANNON: I think it would be a mistake to assume that Rick isn’t empathetic. But empathy and 25 cents won’t even get you a cup of coffee.

BAHRANI: And that’s the tension that the audience is going to feel, which is people feel increasingly that hard work doesn’t get you very far.

SHANNON: Rick reaches out to Dennis out of empathy; he doesn’t have to do that. It’s kind of funny because when we were shooting, Andrew was very passionate about [how] Dennis is in a poverty situation—he doesn’t have a job and he’s loosing his home. He’s got these ideals and these things he stands up for, this whole notion of his tools—he’s got his tools back. When we were shooting that scene [where he says], “I’m not leaving without my tools!” finally we just had to be like, “Look, Rick Carver does not give a shit about your tools. And it’s not because he’s mean, it’s because he’s got a house that’s filling up with raw sewage while your having this conversation.” Rick is wealthy and he’s successful, but it’s because he works his ass off. Its not like he just goes and breaks into ATM machines and takes money. He goes out and he gets the money. It was like, “Let me show you how this works, because you can’t save yourself. Even if you get your tools back, you’re not going to have anything to do with them.”

BAHRANI: His character understands that we are in a game and the game is very rigged. The real heavy is the system, and the system here is mainly the banks and the government. There are others: Freeman, the attorney, who is based on a real guy, the foreclosure king of Florida. He was doing about 40,000 evictions a year—was guilty as hell for robo-signing and never went to jail. At the end of the film, the guy is a snake; he’s got to slither off. I think Shannon’s character understands that, and I think as an audience we feel that: what does it mean when 85 human beings have as much wealth as 3.5 billion people? Even since I made the movie, just a year and a half ago, if I wanted to retitle it to today, it would be called The 99.9 Homes because it’s changed even more. The movie came to Venice and to Toronto, and the press was saying that all three actors—Michael, Andrew, and Laura—were going to be nominated for Academy Awards. I love to hear that, and I hope that happens because they were so good in the film, and they were so dedicated. They went to Florida, they did the research; they asked so many questions. Andrew pushing for that thing he wants, Michael pushing back. Michael and Andrew have very different techniques of acting, and they needed different things from me. And because each was relentlessly going forward for what they want, which is correct for any human being, or actor, it created great spark on camera. There was an energy between them—an explosion between them. I thought I had a good framework in the script—I had great co-writers—but I feel with the actors they were able to take it one more place. Either they understood the characters one level deeper than we ever did as writers, because they started to live and breath in a different way—they were actually wearing a costume. Or they had a different specific take on it that matched their own vision, and there was an ability to step back and allow some of that to happen, which I think provided for the energetic scenes.

BROWN: When did you realize that Michael and Andrew had such different ways of preparing and would need different things from you? Is that something you knew right away, or figured out?

BAHRANI: I had a feeling about it. I knew Michael from before and I had known Andrew a little bit, we had met at a mutual friend’s wedding and he had come to one of my classes one time, unannounced, he just showed up in the back. Of course my students were so excited, “There’s Andrew Garfield sitting in the back!”

SHANNON: [laughs]

BAHRANI: In talking to them I had a feeling that they would need something different, but then at a table reading we did in New York, months before we shot the film, it was clear that they had a different way of working. I would tell [my co-writers] about my meetings with them, what they told me. The more I knew them, the more I would try to weave in a mix of who they were and how they saw it. Originally, Andrew’s character was my age, and then when he popped up as an idea for the lead, I rewrote it for someone age 30. Then Andrew came and said, “I think I should be 27.” And when I said, “Why?” He said, “Because at 30 I would be more fully formed, at 27 I would be more susceptible to a mentor or a father figure even if he’s corrupt.” I never thought of that. Those were the things that the actors were bringing into the film. There was one time early on when I was still trying to figure out who the characters were now that there was someone actually doing it. I said, “Michael, don’t you think it would be this way?” and I could tell that there was a pain in Michael’s face about what I was saying. We did a take and he was gracious, he did it like that. I could see him coming over to me to tell me, and I just said, “Michael, please ignore what I said. It was such a horrible idea. Dumb as hell. Just go back to what you were doing.” But he was gracious enough to show it to me.

BROWN: Michael what would you have done if Ramin was like, “That was amazing!” And you still felt unsure?

SHANNON: I always want more takes. That’s the downside of working with me. I have a very hard time walking away from scenes. Now it’s gotten to the point where I think directors have figured that out and they’ll actually come up and say things like that, and I become paranoid. I think, “Do they really mean that or are they just trying to move on?” ‘Cause I’m like a pit bull, and the scene is your ankle. I’ll just bite it and I don’t want to let go. I know, when you’re done with the scene, you don’t get to do it again. That’s it!

BROWN: Do you always use the last take when you’re editing?

BAHRANI: Not always, but it’s usually the last couple of takes. Unless, specifically, we don’t know what’s going on in a scene and I want to see different types of things. Or an actor wants to give different things. If an actor asks, it means they don’t know. And if they don’t know, you better fucking get a couple variations because the editing room is going to be your master. The editing room is then when the movie gets rewritten for the third time. You have to be open to the film being rewritten in the edit room—that it changes there, that you take a different performance.

BROWN: Obviously 99 Homes is about a wide social problem, but do you think the film could have been set in another state in the U.S.?

BAHRANI: It could have been in any state, but there were four particular ones: California, Arizona, Nevada, and Florida. California sounds like pornography, and the other two sound like gambling and prostitution, and the Wild West. Florida sounds like Disney World and retirees and golf. That sounded the cleanest to me. Orlando, specifically, because of Disney. The golf courses seemed like where I should put the corruption.

BROWN: But what about the gun violence?

BAHRANI: [laughs] Well, of course Florida opened its doors to me and said, “We have this too!” But I think the movie could be understood in any country. We showed the film in Greece. They’re in a mess. One of the guys at the screening said, “I’m getting kicked out of my house in three days.” Someone from Croatia who saw the film told me it reminded them of when they lost their home in wartime. I think anyone who wonders how to protect their family or themselves, or how to survive—which is everyone basically right now except for the .1 percent—knows these emotions.

BROWN: Rick tells Dennis not to get emotional about real estate. Do you agree?

BAHRANI: I don’t know, I shouldn’t say.

SHANNON: I live in Red Hook in Brooklyn, and it certainly seemed like a bad idea to be emotional about real estate after Sandy. I would walk up and down Van Brunt Street and watch people pumping water out of their destroyed homes. People making decisions: should they stay or should they go? But it’s a very primal thing, the sense of home. Particularly in the world today when there’s so many people. The idea of having somewhere you can go and be safe and also be away from the world, it’s hard not to be emotional about that.

BAHRANI: Especially if you have family—if you have some emotional memory there, family, mom, dad, kids, lover. Whoever.

SHANNON: It’s really funny though because, when I was a kid, we moved around all the time. I went to visit my mother recently in Lexington, Kentucky, where I grew up. I said, “Mom, you remember that one house we lived in when I was in sixth grade and you got divorced, and it was terrible year and it was a nightmare? We’re pretty close to that house aren’t we? Let’s go by it. Just for old times sake.” She said, “Okay.” So we’re driving down the street, we’re on the right street, and I’m looking at the houses, and I’m like, “Is it that one? Or is that one?” I was so sure that I would recognize it as soon as I saw it, because I had such strong emotions and memories associated with it. And both me and my mother just sat there in the car in the street and scratched our heads and finally just gave up and drove away.

99 HOMES IS CURRENTLY SCREENING AT THE SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL IN PARK CITY, UTAH.

For more from the Sundance Film Festival 2015, click here.