exit poll

Sofia Coppola’s “On the Rocks” Doesn’t Go Down So Smooth

Exit Poll is a series exploring the good, bad, and outright deranged films and events our editors are attending. This week: Shanti Escalante watches On the Rocks, the latest film by director and writer Sofia Coppola.

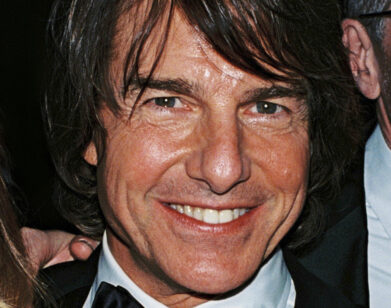

Similarly to Sofia Coppola’s sophomore success Lost in Translation, Bill Murray plays the father figure in her new film On the Rocks, which premiered at the New York Film Festival last month. But unlike Lost in Translation, this movie doesn’t go down so smooth. The plot rings familiar: Laura (Rashida Jones) is a comfortably rich but emotionally drained mother of two living in New York, and when her husband (Marlon Wayans) starts traveling frequently for work, she suspects he may be cheating. Laura turns to her father, Felix (Murray), for advice—after all, he cheated on her mother when she was a child, so he ought to have some insight on her own marital problems. When Laura backtracks and insists her husband probably hasn’t done anything, he gently corrects her, “You need to start thinking like a man.” He gallantly begins her education on the subject by compulsively delivering trivia on the supposed biological root of our gendered social dilemmas; tits evolved into their current form to trick men into thinking they were seeing the round humps of the quadrupedal’s ass. (Need I say more?) One private investigator later and they’re on their way to a father-daughter adventure, complete with an overnight stakeout.

Had Coppola’s name not been stamped on it, it would be almost impossible to tell that she’s behind this film, a departure from her auteuristic oeuvre. Coppola, always interested in the seductive and fantastical elements of the feminine mystique, instead concerns herself here with the cliche of the tired modern mother. Laura is somewhat sexless, drained of creative energy, and whittled down by her domestic duties. The exhausted mother is not a fundamentally flat character (Jenny Offill’s Department of Speculation would prove that wrong), yet Laura remains dull because she so conveniently falls into all the expected tropes, while still somehow maintaining an impossibly perfect life. Her children exhaust her, but all they do onscreen is giggle and sleep. Even their messes are enviable; she picks up a few scattered stuffed animals and a sock or two, rather than mounds of legos pried from the sticky fingers of a child mid-tantrum. She has copious time, daytime no less, in a luxurious home office to write, even though her profession is hardly alluded to. While hints of infidelity threaten her marriage, the film shows few tensions or resentments between the two. He is the Mary Sue of husbands.

Even Coppola’s rich aesthetic eye is nearly absent. Coppola is much more comfortable creating consistent, imaginative, and meaningful worlds out of the past than from the present-day elite, who hardly exhibit the considered taste of Marie Antoinette. The occasional statement comes in the form of Felix, from his dapper suits to his cherry-red Alfa Romeo. These color pops leave a garish stamp on an otherwise muddy palette, but they do serve to highlight a thematic inconsistency that runs throughout the film. Felix incites a nostalgia for a kind of classic, benevolent patriarch who has a European instinct for living well. While his unprogressive worldview is low-hanging fruit, Laura never quite pushes back against it, as the film invites us to ogle at a city where people went to the St. Regis and had close relationships with their doormen, bellhops, and car drivers—forgetting, for a moment, that it never really existed.

Laura’s passivity stretches to frustrating ends. Eventually, the emotional tension of the film withers, and we’re left unsatisfied. There is something disjointed in their stilted, cross-generational dialogue, and a closer look at the film’s racial makeup can hint to why. Coppola likes to focus on questions of gender that are uncomplicated by race, and this remains the case; the script is nearly colorblind, until Laura and her family’s Blackness becomes convenient. Coppola offers up Laura’s “modern” family as a self-evident counter to Felix and what he represents—a hollow yet appropriate gesture for the times of #GirlBoss feminism and conservative women on the Court. Ultimately, if Laura lacks an articulated rebuttal, it’s because Coppola does too.