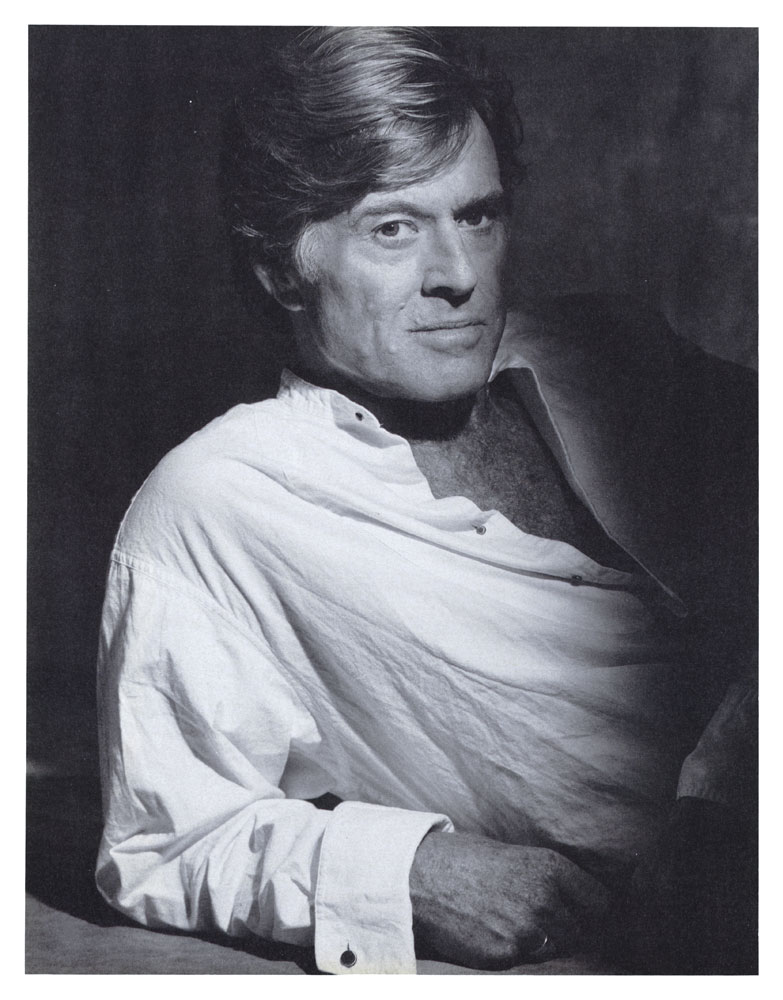

New Again: Robert Redford

Known as an actor, director, producer, businessman, environmentalist, philanthropist, and one of the founders of Sundance Film Festival, Robert Redford has a long list of titles attached to his name. In recent years Redford has appeared more frequently behind the scenes instead of on-screen, but next week marks the premiere of his latest acting role in Ken Kwapis’s A Walk in the Woods as Bill Bryson, a man who after spending two years in England returns to America and reconnects with his homeland by hiking the Appalachian Trail. A Walk in the Woods will debut at one of Redford’s most established endeavors, the Sundance Film Festival, so we took it upon ourselves to find his cover interview from our September 1994 issue, published just before the release of his film Quiz Show.

Robert Redford

By Hal Rubenstein

It’s a long trail from the Sundance Kid to the Sundance Institute. Or is it? Not for a moment has Robert Redford paused to contemplate his monumental fame as a handsome American Galahad. Instead, he has single-mindedly parlayed his success into working for the environment and creating a home for independent filmmakers. And as a director himself, he’s made personal, principled films, such as this month’s Quiz Show—a trenchant fable about how a nation’s faith was sold out by hucksters and opportunists. Sound familiar?

I first met Robert Redfor 25 years ago. He’d arranged the meeting because of a feature I’d written in my university paper praising Downhill Racer (1969), which he’d starred in and executive-produced. In reponse to Paramount Pictures’ indifference to it, Redford chose to personally “peddle” (his word, not mine) the movie to students in hopes of sparking their interest. He greeted me like the Sundance Kid—hat included—radiating charm and only lacking one of those star filters that make an actor’s eyes twinkle. He was soft-spoken and humble, and he asked for help for his movie without a trace of arrogance because he believed in its message. By the time he’d left, I wanted to rent a theater to show Downhill Racer to all my friends.

Redford doesn’t look like the Sundance Kid anymore, though he seems unaccountably taller and still has the best head of blond hair. But what is most striking about him is that, over the years, he has probably put his money, his mouth, his time, his energy, his intelligence, his expertise, and his muscle more fervently into the causes he believes in than any other Hollywood name-above-the-title. What’s more, his commitment to the environment, to the dignity of American Indians, and to the artistic growth of independent film and new moviemakers through the work of his Sundance Institute has been carried out without any need for applause.

Redford is no mooncalf. He’s a savvy enough star to tknow the value of blockbusters, and he has toplined films from The Sting (1973) to Indecent Proposal (1993) without uttering any they-made-me-do-it apologies about compromising one’s art. But when it comes to the output of his own Wildwood Enterprises, he brandishes his convictions. The four features he has directed—Ordinary People (1980), The Milargo Beanfield War (1988), A River Runs Through It (1992), and this month’s Quiz Show—have virtually nothing in common, but they spring from a single source: Redford’s belief in the eternal bonds of family and responsibility to the community, and an understanding of the irreversible damage caused by suppressing truth. Of the films he has helped produce, Downhill Racer and The Candidate (1972) deal with the disparity between the popular perceptions and personal realities of those who achieve fame.

Quiz Show, which re-creates the 1958 scandals surrounding the rigging of NBC’s Twenty-One and CBS’s The $64,000 Questions, brings all these elements together with the lean elegance, dazzling clarity, and quiet power of the gleaming Chrysler 300 convertible that appears in the film’s first sequence. I won’t have to think about renting a theater this time. Robert Redford can fill it all by himself.

HAL RUBENSTEIN: Judging by the initial buzz, you’re going to have a lot less trouble making people aware of Quiz Show than you did with Downhill Racer.

ROBERT REDFORD: Downhill Racer was my baptism of fire as to how this business operates. Paramount probably felt they were appeasing me, but I really busted myself to make it for about $16 million, in an effort to prove that quality is possible on a low budget. Unfortuantley, I was very naïve about distribution. Because I knew the film wasn’t mainstream, I asked Paramount not to wide-release it. They didn’t listen to what I or the movie had to say. They dumped it.

RUBENSTEIN: It was one of the first sports films that didn’t reflect the spectator’s point of view or assume that an athlete is a hero by definition.

REDFORD: I wanted to illustrate how we’ve been raised with this false legacy, that it doesn’t matter whether you win or lose, it’s how you play the game. It’s bullshit. I learned that the hard way.

RUBENSTEIN: You have much more clout now as a producer-director. Has it become easier to do personal or “small” films?

REDFORD: No, it’s as hard as it ever was. The industry has become more centralized, more costly, and more formulaic. It’s so much about the opening weekend, about volume. You watch certain films and say, Why did that get made? How’d they spend that kind of money on that film? And you realize that there’s an assembly line moving through the industry—a product line. So many personalities and directors making films now bring with them a mentality honed by their work in television. Their style is more overt, like sitcoms or the funny-paper pages. “O.K., folks, here’s a tale that can be told in four panels…”

RUBENSTEIN: Yet none of the films you’ve directed have strayed far from the ethic of Racer.

REDFORD: No. You do what you do, finally—you can’t help it.

RUBENSTEIN: Does that make it harder to be involved in a film, especially a commercial one, solely as an actor? Were you antsy making Indecent Proposal, or could you sit back and enjoy it?

REDFORD: That was a bit of a joyride. I thought it was definitely a wonderful part. And since it didn’t require that much time, as you can tell, it enabled me to edit A River Runs Through It simultaneously. But I was very intrigued by working with a director [Adrian Lyne] with such a strong visual sense. Curiously, directing my own films have made me more tolerant and patient. I’ve always been an extremely impatient actor—you know, not too many takes, don’t want to spend too much time on the set. Waiting around drove me nuts. But now I’m much more sympathetic to a director’s struggle.

RUBENSTEIN: A film like Indecent Proposal has a very clear setup, an obvious hero, an obvious villain, a see-it-coming climax and the requisite happy ending. All we have to do is watch and chew. Your own films lack those signposts.

REDFORD: You mean, where are my fireworks, like the fireworks at the end of The Natural [1984]?

RUBENSTEIN: I don’t think those signposts are necessarily what audiences want, but it’s what they’ve been trained—

REDFORD: To expect. Well, that’s exactly right. I do it sometimes as an actor, but as a director, I’m not so attracted to that. The art of making a film and its content are far more interesting to me than the result or impact. Of course, you hope it has impact. In fact, I think more broadly now about what an audience requires, but I want an audience to be fascinated by the process of finding an answer, or finding out there isn’t one.

RUBENSTEIN: The one element that underscores all the films you’ve directed is that they’re quiet.

REDFORD: Yeah, I think “quiet” sometime is a greater power than noise. It can harbor and reveal feelings that can’t be expressed.

RUBENSTEIN: But audiences have a short attention span, by and large.

REDFORD: Like I said, thank television. If they do have a short attention span, it’s only because it’s what they’re used to: not much subtlety, not much restraint, not much time to let things unfold—as often happens in life—and everything accelerated in a stylist way with a lot of zing.

In fact, the first part of Quiz Show is meant to illustrate this TV technique. It covers a lot of ground in a short time: setting up the machinery, setting up the characters—the sponsor, the network, the producers, the manipulators, the merchants, the victims. We have to see the worlds of both [Twenty One contestants] Herbert Stempel [John Turturo]—unpriviledged, noisy, colorful—and Charles Van Doren [Ralph Fiennes]: rich, tweedy, part of the cultural-academic elite, sitting among trees and flowers at the country home. Then there’s [congressional investigator] Dick Goodwin [Rob Morrow] and his agenda. It all had to be done very quickly, so the first part of the film zips along. Then, as it goes into the story, it slows down so you can understand why things are happening, only to accelerate rapidly at the end. It’s a conscious rhythm, and a lot of it had to do with my feelings about television.

RUBENSTEIN: Which are?

REDFORD: Well, I grew up in a period of transition. I did not, like my children and people today, grow up with television as part of my life.

RUBENSTEIN: You didn’t watch the quiz shows?

REDFORD: Radio, newspapers, they were normal parts of my life. In those days, you had to go somewhere to watch television and leave something to see it. I remember the first time I ever saw television. My folks drove—drove—my brother and I to a place called Hawthorne, California, six miles from where we lived in Santa Monica, to an appliance store at night. People were gathered outside this window, where the TV had been left on inside after closing. And I remember seeing a guy named Bill Welch on KTTV, incredibly boring, saying absolutely nothing about anything. But we stood there glued to this window, just because that man talking was actually talking somewhere else in the city and we were seeing him. It was a miracle. The idea was to set Quiz Show at this time of naïve energy, when television’s audience tended to believe what it saw as what really was.

RUBENSTEIN: What’s so disturbing about Quiz Show‘s exposing this collective naïveté is that even when we learn that both Stempel and Van Doren are cheating, we only want to forgive Van Doren. Once we’ve made a hero, we’re reluctant to see him as anything else. Do we need heroes that badly?

REDFORD: Our culture insists on it, and it makes better storytelling, but we also need that fall from grace.

RUBENSTEIN: It seems incredible that the real Van Doren became a major celebrity.

REDFORD: Worse. He became a role model.

RUBENSTEIN: I was just old enough to watch the quiz shows, and I remember him as the star of Twenty-One.

REDFORD: I had just arrived in New York from California. I was 19 years old and excited beyond belief. I was an art student and an acting student and behaved as most young actors did—meaning that there was no such thing as a good actor, ’cause you yourself hadn’t shown up yet. I’d go see John Gielgud appearing in Ages of Man and I’d say, “Yeah, well, it was O.K., but…” I enjoyed nothing. And I remember watching television—by now I had a television set—and resenting that I was watching it. I was pissed, ’cause it was sucking me in, and I couldn’t resist it. And I watched Van Doren because he was rising, rising, rising, and he had this kind of…there was an arrogance about him. Yet he feigned a kind of innocence. And as I watched him coming up with these incredible answers, the actor in me said: “I don’t buy it.” I remember that vividly. But what’s weird is that I never doubted the show. I didn’t take it to the next step and say, “The show’s rigged, it’s all bullshit.” I just didn’t, I couldn’t. that’s how innocent I was. Because, as yet, we had not had an event in our history that had devastated our belief like this experience would. And when the scandal hit, I remember some slight feeling of vindication. [pauses] I was actually on a quiz show once.

RUBENSTEIN: Which one?

REDFORD: A show Merv Griffin hosted, Play Your Hunch. It was in 1959—the year after the scandal hit.

RUBENSTEIN: Were you coached?

REDFORD: No, I was on as a subject—actually more like a stooge. At the audition, the guy said, “So what do you do, kid? Where are you from?” And I said, “Well, I’m an actor from L.A.” And he said, “C’mon, you can’t be an actor on the show. Think, think, think! What else have you done?” And I said, “Well, I’m also an artist.” “O.K., good, that’s it—you’re an artist.” So when Griffin came up to me and said, “Where are you from, Bob?” and I said, “L.A.,” he was ready with a few jokes about L.A. and when he said, “What do you do?” and I said, “I’m an artist,” he was ready with jokes about art. Oh, it was so awful, just so horrible. But what impressed me was that I could feel the hype. I mean, people would talk to me normally backstage—and suddenly the show went on [snaps fingers] and [loudly] EVERYBODY WAS TALKING LIKE THIS. Everybody was hyperventilating. At first I went, “Jesus, this is cornball.” I was so calculated, but then it got to me.

RUBENSTEIN: What did you have to do on Play Your Hunch?

REDFORD: Two other guys and myself stood silhouetted behind three screens while in front of them stood one of these other guys’ twin brother. The contestants had to guess which one of us was the twin. I only did it because they promised me $75. I was really poor in those days, and my wife was pregnant. I was humiliated by the idea, but I needed that $75. However, when the guessing was over, the announcer cried, “And now, the prize for our subjects. From Abercrombis & Fitch—a fishing rod!” Afterward I went up to the guy and said, “Where’s my dough?” And he said, “Well, the rod’s worth $75.” I was fried.

RUBENSTEIN: The way you’ve directed Quiz Show, it’s 100 percent nostalgia free.

REDFORD: I hope so. The technology available for filmmaking now is incredible, but I am a big believer that it’s all in the story. I believe in mythology. I guess I share Joseph Campbell’s notion that a culture or society without mythology would die, and we’re close to that. I don’t know what your childhood was like, but we didn’t have much money. We’d go to a movie on a Saturday night, then on Wednesday my parents would walk us over to the library. It was such a big deal, to go in and get my own book. I dove into mythology, and that was the most important thing I ever did, for it was full of all these larger-than-life things, windows into greater possibilities, other realms. And then in first or second grade, I had the benefit of a teacher who read us Laura Ingalls wilder—Farmer Boy and Little House on the Prairie—in such a way that we were there. You could tell she really got off on it, but we did, too. Those two things led me into life with a tremendous respect for storytelling—that and the way my family communicated.

RUBENSTEIN: We usually imagine the ’50s drenched in Happy Days kitsch. But Quiz Show has the look of that Chrysler 300 you show at the start of the film—sleek, a little cold, but ready for the future.

REDFORD: I wanted to be there as though it were happening for the first time. That’s why that scene in the automobile showroom starts the film. I wanted to present the postwar realization of the American Dream as it was unfolding without editorializing.

RUBENSTEIN: And that dream revolved around a fabulous car.

REDFORD: And that Chrysler 300, in my memory, is it. It beat the Cadillac Coupe DeVille, it beat the Eldorado. But what is that man, Dick Goodwin, the investigator, doing in that room? He has no business being there. So right away you’re setting up that here is a very ambitious guy. The one thing all three characters—Goodwin, Stempel, and Van Doren—had in common was their greed, their ambition to make the myth real. And so the opening scene says right away how America was in a rush to act and think big.

I tried to create in Quiz Show the story of these three lives, because what attracted me was the slice of social life each one represented. Stempel represented a coarse, unpolished world. Goodwin was caught between the ambivalence of wanting to champion him, but being embarrassed by him at the same time because he was an annoying fellow, and wanting to be close to Van Doren, whom he looked up to, even though he knew he had auctioned off his morality.

RUBENSTEIN: which brings us back to the hero dilemma. Is there anything in the structure of the story that tricks us into siding with Van Doren for as long as we do?

REDFORD: Don’t you think the public did?

RUBENSTEIN: Yes. But what bothers me is that I sat there knowing full well he was a liar. Ralph Fiennes plays him as a good-looking, erudite charmer who seemingly has the life we all want—whereas, what is there about Stempel’s or Goodwin’s lives we want?

REDFORD: I have to admit there’s a little bit of a cheat going on, and it was a tough one for me because am among the minority of people not sympathetic to Van Doren—he offended me. I probably took some license. He made his Faustian bargain, but he made it much more clearly than I show. I made a choice to show the corruption of the innocent, so it helps to make him less knowing. It’s more tragic because he’s less knowing. But, in truth, I didn’t believe him.

RUBENSTEIN: By the end of the film, I despised him.

REDFORD: Good.

RUBENSTEIN: Because of what he does to his father, the Professor [Paul Scofield]. The “chocolate-cake scene” between the elder and younger Van Dorens defines the inflexibility of what is inherently right and wrong.

REDFORD: Paul Scofield is so good. When I was doing the research, what interested me was, what did Van Doren do when he had to tell his father he had cheated? What was that like? Young Charlie is quite a guy—he’s incredibly manipulative. And so you’ve gotta have somebody that’s pretty strong to go up against him. But the father can’t comprehend his son’s choice. It’s a crucial moment in the film. See, I think shame is pretty well gone out of our vocabulary. When I grew up, shame was used as a tool for check and balance. If you stood a chance of hearing someone say, “Shame on you,” or “You should be ashamed of yourself,” you thought twice. It doesn’t seem to be a factor today. You see [Senator] Bob Packwood, all those guys up there, Oliver North—you can just feel their not telling the truth. And it’s so brazen. If they have any shame, it’s not for what they’ve done, but for getting caught at it. At one time, it might have been, Oh my god, what’s gonna happen to me? Now it’s, Hey, you know how you deal with that? Treat it like nothing happened and people will respond the same way.

RUBENSTEIN: It’s the Watergate technique.

REDFORD: It’s Nixon’s legacy. Watching reporters try to dig up all his achievements when he died, as if he’d been a venerable statesman—that was a tough moment. Nixon’s legacy isn’t China, or foreign policy, but the fact that he never could say, “You got me, I feel shitty.” Garry Wills encapsulated it best with his theory that I was all about Nixon’s need to fail big. The one success he could achieve was to fail in the biggest arena possible ‘cauase he was such a loser. Which he was.

We used to have a week called Boys’ Week in Los Angeles; I don’t think it exists anymore. Part of Boy’s Week was these achievement awards. I was 13 and I went to receive an award, and Nixon was there as the senator from California, my senator, with Governor Earl Warren, presenting these trophies. I didn’t have a clue who Nixon was. He handed me the award, shook my hand, spoke to me, and I absolutely got a chill. I thought, This man is cold as ice—there’s not a real bone in his body. Purely a gut reaction. But from that moment on, the meter started ticking with me and Nixon.

So I watched him, and every time I ever saw him, he embarrassed me, as an American, as a man—he embarrassed me. Whether it was the Helen Gahagan Douglas smear, the “Checkers” speech, or blowing it when he spoke to the astronauts who walked on the moon. And then, finally, that last shot of him getting on that helicopter with his hands raised in victory. Well, that’s the kind of stuff Ollie North does, the kind of stuff Quayle will do, because it works. Watch for Quayle—he’ll be here big as a billboard in the next two years. He’s doing the same thing Nixon did, rebuilding his case.

RUBENSTEIN: His book’s a best-seller.

REDFORD: They’re staging all of his appearances. And whenever he’s covered [by the media], there are people smiling. So people will get it into their head that he’s a popular guy and they’ll forget what a dumbbell he is and how totally inadequate he is. He should be a gold pro.

RUBENSTEIN: Do you see a through line from the quiz-show scandals to Watergate?

REDFORD: I see the quiz-show scandals as really the first in a series of downward steps to the less of our innocence. When it hit, the country was numbed by the shock, but it was erased quickly because no one, including Congress, or the networks, wanted to deal with it or hear about it. But the shocks kept coming: Jack Kennedy’s death, Bobby’s death, Martin Luther King. Then Watergate, then BCCI, Iran-Contra, S. & L. And now O.J. I think people may look at this film and say, “Well, as a scandal, big deal.” But in a historical context, it’s very much a big deal. This was the beginning of out letting things go. And what did we do about it? Kind of nothing, as long as we kept being entertained.

RUBENSTEIN: If you listen to people’s responses to the O.J. Simpson case, there is this refusal to believe that he could have done anything. People are screaming, “Go, O.J.!”

REDFORD: And Oliver North can’t be lying, ’cause look at all the medals he’s wearing. Reagan can’t be as ignorant as all that, because he was president. We’ve always been a brinkman society, always saving ourselves at the last minute. Watergate was the ultimate example. But we’re pushing our luck. We’re focusing on the wrong people, we’re concerned with the wrong issues. When the quiz-show scandals hit, the Van Doren family was so illustrious—poets, educators, editors—so God Almighty. At that point in our history, I seem to remember that academics still had a berth reserved for them on the covers of magazines. You didn’t see movie stars quite so frequently on the covers of Time and Newsweek. Almost from the time that this happened, a shift occurred. I have a theory that Van Doren’s collapse brought down with it the notion of academics as the people of the highest calling and that they never regained their palce. In the meantime, the media, show business, and anyone who knows how to play off them has steadily moved up. I would be curious to know if there were some sociohistorian around who could put some teeth into this idea. It’s my impression that this event is much more marked in history than anybody knows.

RUBENSTEIN: Goodwin enters into the film swearing he is going to get television. He leaves swearing television is going to get us.

REDFORD: Because it keeps on coming at us, because it can make us look at what is wants us to, and make us avoid all the things we need to look at. O.J. is much more compelling and easier to comprehend than health care or the environment. Television tells us only the things it wants to. It still feeds us heroes, it still offers villains. And even though we know better than to always trust it, we still watch.

RUBENSTEIN: Does that make us cynical or stupid?

REDFORD: Both.

RUBENSTEIN: And what does that make you?

REDFORD: Nervous.

THIS INTERVIEW RAN IN THE SEPTEMBER 1994 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.