New Again: Richard Gere

The Interview office walls are lined with our covers from the 1980s: smiling, hand-painted portraits in the decade’s glorious turquoises, yellows, and purples. Most of the covers still hold up today—the familiar faces of Susan Sarandon, Jack Nicholson, and Michael Jackson—with a few no-longer-knowns scattered amongst them (anyone remember Clio Goldsmith?). One cover that sticks out, however, is Richard Gere’s, the mainstream heartthrob of the ’80s and early ’90s who celebrates his 63rd birthday on Friday.

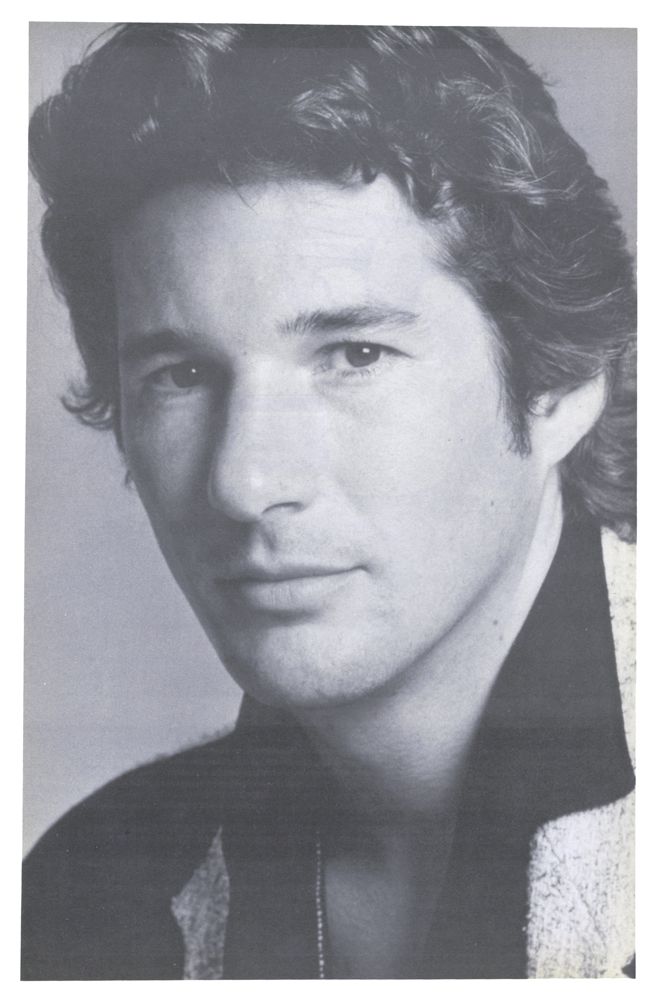

Our first meeting with Mr. Gere took place in October of 1983; An Officer and a Gentleman (1982) had just introduced him as a lust-object, a status Pretty Women would confirm. Gere was just beginning Francis Ford Coppola’s The Cotton Club, alongside Diane Lane, another Interview ’80s cover star, with whom he would reunite for Unfaithful and Nights in Rodanthe. Gere would go on to become a Buddhist activist and marry (and divorce) supermodel Cindy Crawford. In the interview, which we’ve reprinted below, a 33-year-old Gere is already guarded as he talks to Andy and Maura Moynihan about jazz, Duke Ellington, Graham Greene, getting into character, and the Falklands. Gere’s boyhood friend, Herb Ritts, was on hand to photograph the actor.

Richard Gere: Beyond the Limit with the star of the Cotton Club

by Maura Moynihan and Andy Warhol

There are only a few names that guarantee a movie an impressive measure of critical attention and box office rewards, and, today, Richard Gere is one of them. The combination of his enigmatic smile, sparkling eyes, and frank sensuality has won him a faithful following, but he has earned his success through persistence and dedicated effort. One of five children, Gere was raised on a farm near Syracuse in upstate New York, and describes his childhood as “normal and all-American.”

In high school, he was an avid musician, playing four instruments and composing scores for amateur musical shows. He spent one year at the University of Massachusetts before dropping out to pursue acting, landing a job as a repertory player with the Provincetown Playhouse on Cape Cod. When the season closed, he drifted about the East Coast and eventually made his way down to New York. Shortly thereafter, he won the lead role in a rock musical called Soon, which closed after one performance. Undaunted, he moved to London in 1971, where he played supporting parts in several plays, which led to the role of Danny Zuko in the long-running musical Grease. When he returned to New York, he filled the same role in the Broadway production. He went on to win critical recognition for his portrayal of a convicted murderer in Sam Shepard‘s Killer’s Head and, just as his fortunes as a stage actor were on the rise, Gere became disenchanted with theater and started to pursue film work. He played minor roles in Report to the Commissioner, Bloodbrothers, Baby Blue Marine, a romantic fugitive in the exquisite Days of Heaven, and turned in a brief but startling performance as one of Diane Keaton’s lovers in Looking for Mr. Goodbar. In 1979, he starred in John Schlesinger’s Yanks, which did not fare too well at the box office, but established him as a serious and capable performer. Next came his portrayal of a sleek hustler in Paul Schrader’s American Gigolo. The film was provocative, controversial and a hit, securing his status as a major romantic lead. He then took a short respite from Hollywood to take on the complex and grueling role of a homosexual prisoner in Nazi Germany in Bent, a career gamble that paid off, earning him unanimous raves. But nobody, least of all Gere himself, predicted the astonishing success of An Officer and a Gentleman, the runaway hit of 1982, which has grossed more than $125 million. His next project, Breathless, won him more critical acclaim and respect. Immediately following the completion of Breathless, Gere flew to Mexico to film Beyond the Limit with Michael Caine, a drama of love and war based on the Graham Greene novel, The Honorary Consul.

Gere’s durability as a romantic hero coupled with the growing appreciation of his talent has put him at the top of his field where he can be selective about his roles and contribute substantially to the projects he’s involved with. Directors marvel at his concentration, leading ladies at his charm. Andy Warhol and I spent a long, hot afternoon at the Astoria Studios in Queens where Gere’s current venture, Cotton Club, was in pre-production. We found him alone in a small room studying ancient tapes of jazz musicians and toying with an exquisite silver trumpet.

MAURA MOYNIHAN: Is this an authentic Cotton Club trumpet?

RICHARD GERE: No, but mine is, actually. A friend had found one down in New Orleans, and when I was looking for the right kind of cornet he said he had one and he sent it from LA. It was perfect—1920s. This one is a little different.

MOYNIHAN: It looks like sterling. It’s beautiful.

GERE: Silver-plated.

ANDY WARHOL: I was going to start collecting trumpets because a friend of mine collects them, but we couldn’t find any. You’re supposed to go to pawnshops.

GERE: No, you can’t find them any more.

WARHOL: Somebody collected them all, I guess.

MOYNIHAN: I met you once at Susan Sarandon’s going-away party from Extremities and you were wearing the most incredible pair of cowboy boots that I’ve ever seen in my life. They were gorgeous.

GERE: What do you mean, cowboy boots? I’ve never had cowboy boots.

MOYNIHAN: Really? They looked like them.

GERE: Oh yeah, those things. No, those are gaucho boots from Brazil.

MOYNIHAN: What’s the difference between gaucho and cowboy?

GERE: When you say cowboy boots I think of Texas: Tony Lama boots. But these are handmade boots from the gauchos.

MOYNIHAN: Who is writing Cotton Club?

GERE: There’re several writers. The latest draft is by Francis Coppola. But William Kennedy just came in to work on it too. He has written a trilogy called The Albany Trilogy. They’re three great books—wonderful ’20s, ’30s, tough-guy stuff.

MOYNIHAN: What made you come to this project, the Cotton Club? Were you attracted to the period, the music or the characters?

GERE: I suppose it was the music. I think I always wanted to do a character who, on some level, wanted to be black. And this character is generally in that mold.

MOYNIHAN: Are you actually going to play in the film?

GERE: I think so. It depends. Sometimes you do 20 takes. I’m never going to be that good. These guys work 20 years to get that strong. It depends on a lot of things. I just have to be pre-recorded, that’s the only way.

MOYNIHAN: Cotton Club‘s going to have a lot of music, though.

GERE: Oh yeah.

MOYNIHAN: Is it going to be a musical with all the Ellington scores?

GERE: We have the rights to use almost all of Ellington’s music at this point. The decisions haven’t been made exactly.

MOYNIHAN: Will you be using any unpublished Ellington music that the public hasn’t heard before?

GERE: No, because Ellington was a very well-organized man and all of his stuff was published. He wasn’t an undiscovered genius; in his own time he was known to be a genius. He was an excellent businessman, too.

MOYNIHAN: He was also quite a ladies’ man.

GERE: That’s just what I was going to say.

WARHOL: Do you go to the Blue Note [café] at all?

GERE: No. A great trumpet player by the name of Warren Bache has been working with me on the trumpet.

WARHOL: We went to see Dizzy Gillespie about six months ago down in the Village. He’s great. The Blue Note is a good place, you should go. And a lot of kids still like jazz, I never understood why jazz never got big. It’s always sort of ready to explode and then it doesn’t.

GERE: Jazz is more difficult music, you have to listen to it.

MOYNIHAN: When did you finish Beyond the Limit?

GERE: We finished shooting in January.

MOYNIHAN: What have you been doing since?

GERE: We totally re-did Breathless. When I finished Breathless, I went off the next day to Beyond the Limit. The only way I could do both films was to do them back-to-back.

WARHOL: Do you think it was a good idea to re-do Breathless?

GERE: Everybody is happy with the changes.

WARHOL: What did you change?

GERE: First of all, the music didn’t work at all. The changes were basically editing choices. What happened was that Orion had wanted to put the film out very quickly. That forced the director and editor into making very quick choices which weren’t necessarily the right choices. So, when I came back we sort of forced the situation and we didn’t release the film, which allowed us to go back and do a good job with the editing and do some new scenes and additional stuff which is what old Hollywood used to do.

MOYNIHAN: Did you study the original film? How much of a say did you have in the final editing of Breathless, in the script and the editing?

GERE: Oh, a lot.

MOYNIHAN: Didn’t you write a lot of it?

GERE: Yes, we all got involved. People have a different idea of how movies are made than they really are. On a certain level, everyone throws ideas into the hopper. It’s not like the actors are wind-up dolls that you push out onto the floor, play with, then put back in the box. You get people around you who you trust; the writer, the producer, the director and all the actors all contribute.

MOYNIHAN: How do you maintain your concentration on a film set where the action is constantly being interrupted and you film action out of sequence? How do you keep in character?

GERE: The only way I figure it is to keep in character all the time.

MOYNIHAN: So you never break out of character?

GERE: Well, it’s a difficult thing to explain. In the process of developing a character, you do, in fact, start to take him on as a personality. I’ve started behaving here like my character in the Cotton Club. It’s part of my job, they’re expecting me to be a certain way all the time. It’s not like if I come in here with a totally different personality and right before the camera starts they see this new character. It confuses everything. Life has a consensus reality to it and if you use that to your advantage it makes it much easier.

MOYNIHAN: Do you think it’s necessary for an actor to drastically reshape his body for a role or to actually experience extreme pain if it’s something the character will encounter in the script?

GERE: Everyone seems to think they know what acting techniques are. Techniques just help you get to a certain place, but if the thing is happening just by itself you don’t need those techniques.

MOYNIHAN: Do you use specific techniques when you need them?

GERE: I find that you can use a technique when the thing isn’t working, not that you make the technique the end result of your work. You use the technique when you’re in trouble and things aren’t flowing the way they should. It’s a way of fooling yourself to make it work again.

MOYNIHAN: What do you think are your greatest strengths as a performer?

GERE: I don’t think about that. I’ve always maintained that all characters and all personalities are in all of us. The whole thing is available. You’re not this or that, no one is. Andy, how many lifetimes have you gone through? You’re basically a fantasy person and you make that happen for yourself. Anyone can do that if you give it focus and energy. It’s the same with acting; the job happens to be about that, so actors tend to use those muscles more.

MOYNIHAN: How long does it take you to develop a character?

GERE: Every piece is different. Sometimes it’s an external approach where one can learn the skills required, let’s say, learn to play the trumpet and in that process other things happen. It’s magical: through the process of practicing four hours a day you start focusing on emotion and when you pick up the trumpet it’s filled with feeling.

MOYNIHAN: How did you work on Jesse Lujack, your character in Breathless?

GERE: Basically the root of him is music—music manifested by his moods. He uses the energy and emotions of the things around him to his own purposes. There’s not guilt in him. He refuses guilt, he refuses despair. He turns despair around. He’s a funny kind of character; he’s not the kind of person you’d bring home to your mother and father. He’d be pocketing things; he doesn’t see possessions as being personal. He has an outlaw mentality we haven’t seen for a while.

WARHOL: But it’s hard for a person to be that way in 1983, I don’t know why. I loved the set of the movie; it was more of California and LA than I’ve ever seen in a film.

GERE: I don’t especially like LA much.

WARHOL: But it made LA look beautiful.

GERE: There is a way of looking at an awful place from a certain angle that allows it to take on a beauty because it is what it is.

MOYNIHAN: Why did you choose to work on Beyond the Limit?

GERE: It seemed like the right time to do a serious piece about South American politics. It’s set in Argentina.

MOYNIHAN: But you didn’t film there.

GERE: No, but actually, it was a possibility until the Falklands happened. We went into pre-production at the start of the Falklands thing, and it was a British company, so we had to shoot in Mexico, in Veracruz.

MOYNIHAN: Was Mexico a good alternative?

GERE: Yeah, I doubt that the place Graham Greene created was a real place; it was based on Correntes, but the feeling he evoked in the book was a kind of mythical place. Mexico was fine, we found a dusty, dry industrial town.

MOYNIHAN: Does the film express political sympathies or view points?

GERE: No, because it’s Graham Greene [author of the book The Honorary Consul, on which the movie is based] and Greene’s viewpoint is not very clear [in the book]. It’s probably closer to the truth, because any political situation has many sides, especially being outside as we are. We intellectualize the whole situation any way—we don’t have brothers being killed and wives being raped down there. We make our intellectual decisions about that area based on our cultural background and how we live. I remember talking to someone about El Salvador. He said “These poor people are uneducated, they don’t know anything.” But we don’t understand their culture, we’re using criteria that do not fit. Our ideas of health and work and achievement don’t necessarily fit these cultures at all. It’s so different when you’ve got a brother on the other side. Who was right or wrong? What corporate interests were involved in our civil war?

MOYNIHAN: Is this going to be an action movie with battle scenes?

GERE: Not really. It’s much more a psychological trip, although it involves a kidnapping.

MOYNIHAN: Did you go to Argentina to prepare for the film?

GERE: No. I would have if I’d had time. I wanted to very much. I’d been to the Argentina border before, and to Brazil.

MOYNIHAN: Did you enjoy working with Michael Caine?

GERE: Yes, very much, he was very generous, very easy.

WARHOL: It’s magic coming out here to Astoria to see the Cotton Club set.

GERE: It’s a hyper-realist set, too. They’ve recreated the actual Cotton Club interior. Dick Silver, our production designer, found these original photos so he’s making our set from them.

MOYNIHAN: Do you use photographs and films to develop roles?

GERE: Yes.

MOYNIHAN: Is that a method you created on your own?

GERE: Yeah, it’s a method that suits me. I can see the character in a photograph, in the way a guy stands or holds his hands, the way he buckles his belt. I fantasize a lot looking at photographs. I’m sure that doesn’t work for many people. I build a whole photo gallery based around a character.

MOYNIHAN: Are there any particular novels or stories that you want to make into films?

GERE: Oh yeah, I have lots of ideas.

MOYNIHAN: Can you talk about any of them?

GERE: No. But there’s a wealth of material around. There are a lot of things out there.

MOYNIHAN: I think there are a lot of good writers here in New York.

GERE: But it’s rare that a good writer will sit down and write a good script. Writers are greedy too, and they don’t want to work without getting paid. But quality will find its way out.

MOYNIHAN: Do you read the dailies: Variety, The Hollywood Reporter?

GERE: No.

MOYNIHAN: Do you read reviews of your films?

GERE: I do, although I try not to. Sometimes I’ll run across a review in a magazine, and just read it while it’s there.

MOYNIHAN: Do you watch your own movies? Some actors never do.

GERE: About four pictures ago I felt I had to. I felt it was better for the film if I did. I do my work as an actor, but another part of my work goes to the piece as a whole. I can be fairly detached looking at my work and be brutal on myself.

MOYNIHAN: What aspects of your work are most difficult for you?

GERE: I don’t think that way…

MOYNIHAN: You used to sing in a rock band, didn’t you?

GERE: Oh, there were so many of them, the names were all along the lines of The Strangers, The Outsiders.

WARHOL: Were you the lead singer?

GERE: I was the singer and the guitar player, keyboards and, once in a while, drums.

MOYNIHAN: When did you decide to pursue acting?

GERE: It doesn’t have to be a conscious decision that you’re making. You find a direction and go one way.

MOYNIHAN: You were in one of my favorite movies, Days of Heaven.

GERE: When did you last see it?

MOYNIHAN: It was playing downtown a few weeks ago, in a revival house. Do you have plans for another Broadway show?

GERE: I don’t have any burning desire to get back on the boards, as they say. I love making movies.

MOYNIHAN: Why do you prefer working in film?

GERE: Well, the obvious reasons; more people see your work. You perform in front of a camera, so in that sense it’s the same as theater; the crew, the cameraman, the director, they’re your audience. On a film set, there is other energy there that is focused on watching, which is one of the criteria for a drama. You have a basic theatrical experience in film, but you can temper it, you can pull it apart, assemble it and recreate it any way you want. You have more leeway, to create an experience, to create an emotion.

MOYNIHAN: Do you involve yourself in the editing of your films?

GERE: Yes, I do. There is always a question of time, and the director. I’ve worked with a lot of directors who don’t mind my involvement. They appreciated it. I haven’t worked with people who are jealous or competitive. That’s a particularly deadly attitude to have when you’re working on a film. On a movie set that works, you have your father figure, the director, you have your siblings, your other actors.

WARHOL: Susan Sarandon says such nice things about you. We just love her so much; you’ve got to do a movie with her.

GERE: She’s great. She’s one of our best actresses. I don’t know anyone who doesn’t think she’s great.

MOYNIHAN: How long were you filming on location in Mexico?

GERE: Three months there and then a month in England.

MOYNIHAN: Was Veracruz beautiful?

GERE: No, it was hot and miserable.

MOYNIHAN: Did you get sick?

GERE: Oh, I was so sick. They had to take me to the hospital after a day of shooting; they hooked me up to an IV, I’d fall asleep, and at four in the morning they’d wake me up, unhook the IV and carry me to the set. It’s like being in the trenches, especially being on a location like that. But you just have to keep going.

WARHOL: It’s pretty hot in here.

GERE: This place isn’t quite ready for us, but when it is, it’ll be great.

WARHOL: That’s a great story about the IV. People forget how hard it is to be a movie star.

GERE: It was usually 95 degrees and humid.

MOYNIHAN: I’d still rather have that for a job than working in an office.

GERE: Except when you have to get up at five o’clock in the morning and do a love scene and you’re so exhausted and you don’t want to. You think, Oh, leave me alone!

MOYNIHAN: So how do you do it?

GERE: You must do it. You have to have the trench mentality.

MOYNIHAN: Where is Gregory Hines right now?

GERE: He’s here.

MOYNIHAN: Are you going to dance together in Cotton Club?

GERE: No, I’m not going to compete with him. I’m going to stick to the rhumba. He’s absolutely incredible.

MOYNIHAN: Do you go upstate to visit family when you can?

GERE: I haven’t been up there in a while.

MOYNIHAN: You have a sister who’s a dancer, don’t you?

GERE: One sister’s a dancer, a brother is also a dancer, they all do so many things. They’re very creative people.

MOYNIHAN: So you’re close to your family and you see them often?

GERE: We keep in touch and we’re very supportive of each other. But we’re all busy people.

MOYNIHAN: Do they come to all of your openings?

GERE: No, the only one they all came to was Bent. Most of them came to An Officer and a Gentleman.

MOYHINAH: Did you have any idea that Officer was going to be such a hit?

GERE: I don’t think anyone did.

MOYNIHAN: Why do you think it was so successful?

GERE: Like a lot of things, it was timing. Yanks was a very good picture in the realm of An Officer and a Gentleman. But the timing was wrong; the studio didn’t believe in it—it was dumped by the studio. Paramount happened to believe in An Officer and a Gentleman and pushed it. Word of mouth was good. People enjoy seeing a people movie.

WARHOL: I heard that nowadays word of mouth is more important than anything, more than reviews—

GERE: Publicity can buy a certain amount of opening time. You can ensure a picture five huge days with enough advanced publicity. Beyond that, if people don’t like to movie, they’re not going to go.

MOYNIHAN: Do you think there are certain elements a movie must have in order to be successful? Any particular commercial formulae?

GERE: No, I don’t believe in that at all. You can take risks, but people often don’t.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE OCTOBER 1983 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more New Again, click here.