New Again: Mae West

HBO Films and Bette Midler are developing a biopic about American actress, singer, playwright, screenwriter, and general provocatrice Mary Jane “Mae” West. Born in Brooklyn, West made her mark in risqué and boundary-breaking plays such as the controversial Sex (1926), which would see the actress prosecuted and sentenced to prison for 10 days for “corrupting the morals of youth.” After her release, she continued to write and act in the theater, before starting her film career at the ripe old age of 40. Based on her play Diamond Lil, West’s 1933 box office hit She Done Him Wrong was credited with saving Paramount from bankruptcy. In 1943, West left the film industry indefinitely (well, for 27 years).

Interview met Mae back in 1974, when she appeared on our December issue. Anjelica Huston and Peter Lester interviewed the star, who spilled the beans about the idea that sparked Sex and how she dealt with the controversy her work created. —Jacob Bagwell

Mae West: the Queen at Home in Hollywood

By Anjelica Huston and Peter Lester

When talking of the legend that is Mae West, one feels compelled to expound in a sacred language, a language almost as sacred as the rhythm and timbre of speech, a sound that must be unique in this world. She does talk like she sounds in the movies… you know what I mean. Hollywood Boulevard, still dry from the heat of summer, seemed gray and bland; a complete contrast to the apprehension we felt in our stomachs as we drove to interview one of the most innovative stars the screen has ever known. Miss West had specifically requested no tape recorder—an idea unfathomable to journalists—but we were nevertheless prepared to hurriedly write down every word of wisdom that would drop from her lips; little did we know that we would be so transfixed by her magic that it would be hard to write.

THE ROSSMORE APARTMENT BUILDING.

ATMOSPHERE: Misty with climate control. Cream Venetian blinds drawn down. Air conditioner humming lazily. The scene seems to be shrouded in the mists of dry ice.

THE SETTING: Small room, cluttered with carefully arranged memorabilia. An eye that glanced at Versailles and then squinted at Southern California. Cream, white, cream, white. Ormolu for days.

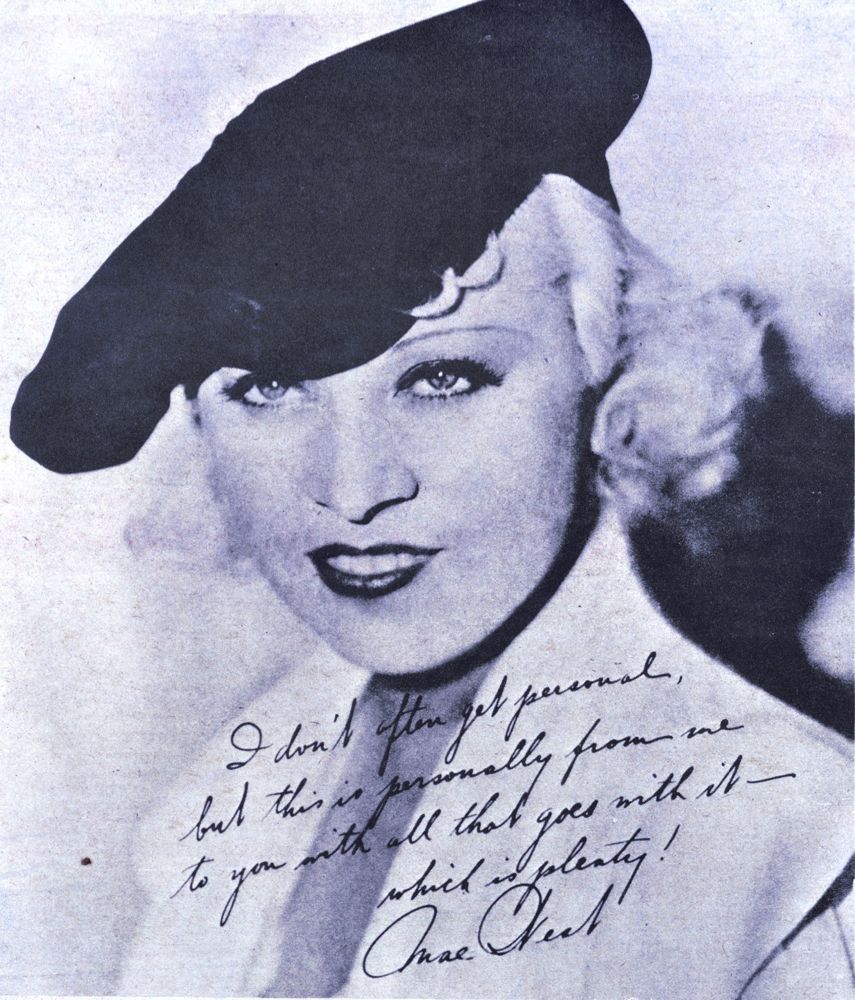

IMPRESSIONS: Grandeur squat on voluptuous legs, heavily embossed surfaces in mirrored gold. Photographs from the past, teasing in sepia furs, Miss West as she was. Photographs everywhere, some standing proudly atop a Dresden baby grand; alabaster nudes, variations on hand to hip, hand to hair, amidst extravagant arrays of artificial floribunda.

We’re dying for a cigarette, but the absence of ashtrays alerts us. Mr. Grayson, Miss West’s personal secretary, indulges his habit out in the hallway. The only visitor ever permitted to smoke had been Bette Davis, and she didn’t overdo it.

Etiquette established, visitors’ book signed, credentials given, Mr. Grayson exits stage left.

Drawn to us as if by a magnetic force concealed beneath the floor, Mae West enters, gliding almost mechanically to her chair. We are close enough to touch her without getting up. Silence as she allows herself to be scrutinised—freshly painted, hair waving softly champagne to her shoulders, shoulders draped in lace. Her eyelids droop shyly as she lifts her gaze, deeply shaded by mink lashes. The pupil of one eye overflowing in its iris; she smiles behind a coral cupid’s bow as she adjusts a lurex cushion to the small of her back; tidies the folds of the shocking pink negligee about her bosom and crosses her legs.

Her hands, beautifully manicured and pearly tipped, lie in her lap, she rubs them together a little nervously at first, suspicious of us until she realizes that we are fans completely stunned by the legend. She relaxes and gives us everything.

ANJELICA HUSTON AND PETER LESTER: To what do you attribute your looks?

MAE WEST: (Tapping her teeth) See—they’re mine…I have no face lifts…it’s all mine? There’s no change in me. I wrote this book about it. It’s called Sex, Health and ESP, you know. I eat the right foods, exercise, take care of myself.

HUSTON AND LESTER: ESP?

WEST: Yeah, I’ve been havin’ these psychic experiences since 1941, I knew this man, the Reverend Jack Kelly… a great man who died in ’65. I was sitting just where I am, sittin’ watchin’ TV here when I heard this voice, whispering, kind of, I felt this presence beside me. Like it was a man in the room. looked down and saw a pair of men’s feet, looked a little higher and saw his legs. It was Jack Kelly all right. He walked here behind me, over to where you’re sitting and then he just dissolved away. Into the sofa.

HUSTON AND LESTER: Are you afraid of them? Have you spoken with them?

WEST: No. You see, they look nice. Once when I was laying in my bed, one came in and just stood there. You see, I don’t drink, so this really happened. Anyway, this one came over to me and stood there by the bed. So I stood up and put my arm up like this to stop him from touching me… I’m not takin’ that chance till I know what they’re goin’ to do.

(Looking up from our wild scribbling, we see that she’s smiling and gracious, enjoying talking as much as we are enjoying listening.)

WEST: Once a friend came here, and I said to him “go over to the piano and play that melody, you know the one, just the melody, forget the lyrics.” So he did, and as I was standing there beside him, listening, this story came to me in 56 seconds.

HUSTON AND LESTER: What was it? Can you remember it?

WEST: No. It was good though. One of my stories, I can’t think which one it was. I had a secretary write it down.

HUSTON AND LESTER: Do you entertain here?

WEST: Off and on. Friends stay sometimes, but mostly at my beach house. It’s got 22 rooms, eight bedrooms with bathrooms, you know, so there is more space. Then there is a ranch I have in Sepulveda. So you see, this is just one place I live in. I wasn’t looking for a home in this apartment, so I just had it fixed up and started to live here.

HUSTON AND LESTER: For how long?

WEST: Since 1932.

HUSTON AND LESTER: Do you feel that people working then in Hollywood were more talented than now?

WEST: Talent… But then, you see, there was so much of an outlet for it. Every studio made a hundred or so movies a year… now they’re down to 10 or 12.

There was always testing… there were talent scouts everywhere. All over the country going to small towns, looking for girls for movies. They never had enough talent then. Now, you see, it is all television. Small scale. We had great artists… great writers working here. It’s not the way it used to be. The young crowd… they watch my movies on TV.

HUSTON AND LESTER: Would you work for TV now?

WEST: Too many people seein’ you for nothing.

HUSTON AND LESTER: To what do you attribute your success?

WEST: I wasn’t aware of what I was doin’, see. I was innocent. I couldn’t help my personality. It was the way I was. (The eyelids lower. The negligee is rearranged to conceal more.) It was my success…From the time I was a headliner in Vaudeville at 17 years old, until then I’d played child’s parts, but I came out to Hollywood and started to write my own pictures. In order to show them what I wanted, I had to write it.

HUSTON AND LESTER: Did your mother encourage you to work as a child?

WEST: Yeah. My father was an athlete, you know. So I got used to that kind of thing, seeing barbells around and all.

HUSTON AND LESTER: And muscles?

WEST: And muscles, yeah. (A suggestion of a blush, eyes down and laughing.)

HUSTON AND LESTER: Those alabaster statues are very beautiful.

WEST: Yes, they’re nice, aren’t they? My manager wouldn’t let me pose for a man. My manager was in love with me. So they found a woman artist. You see the picture behind you?

(An oil painting of a flaxen voluptuary on a canopied chaise, gazing at a bewitched monkey hanging from the bedpost by one hairy arm. The words “SEX” and in smaller print, “Mae West” are written underneath.)

See that? Well, this artist, Florence Kosell was her name, she was here one day and she walked through the bedroom and I was lying there on my bed, so she said, “I must paint you like that.” She wanted it full face at first, but I thought it was kind of brazen, so I say how long will it take to do? She tells me and it’s a long time. So I say, well how long will it take to do it in profile? She says half the time, so that’s how we did it. It turned out good, don’t you think? Maybe the forces wanted it that way.

HUSTON AND LESTER: When was it painted?

WEST: Around the time I did this play, Sex. I was the first one ever to say “sex” on stage. The director was called Edward Elsner, he’d directed all these actresses… Pauline Fredrick, Julia Marlow, that girl—Ziegfield’s wife—what’s her name? You know the one… very fluttery. Well, anyway, I bring him this play, but he doesn’t have his glasses with him. I said shall I read it to you? He says sure. It was called Follow the Fleet, a dramatic play with a jazz band in it. Well, I started reading it and suddenly he says, Oh my God, this is sexy! He says, you have a quality I have never seen in a star before… a sexy quality. I say, where have I got it? He says, I don’t know but you’ve got it, it’s just there, sex. So I just went on doin’ what I was doin’, and he says again, sex, sex, sex, this play reeks of sex. I was hearing the word sex so much I was beginning to like it. “Gee,” I thought, “this might be good for the title, Sex.” So I tell my manager I want to change the title to Sex. He says, if only we dare… so we do! Then there was a lot of trouble. When it opened, the newspapers wouldn’t use the word. They said, “Mae West in that certain play.” Finally we had to hire those sticker guys, you know. You’d leave your car for ten minutes and there’d be Sex all over it. Well, then there was an epidemic of sex plays, all of them using dirty words. I’d never use bad words like hell or damn in my plays. I wrote innuendos, I write the way I feel. It just comes out that way. I’d hit ’em all the way through the beginning, middle and end. My play had a plot, a story. No woman’s going to pay to see other women being slapped around, and these other plays were embarrassing. Sex is only exciting on the inside.

HUSTON AND LESTER: What was your next play?

WEST: Then I wrote The Drag. There were 60 gay boys in it. I wrote it for them, I didn’t act—why? Well, the gay boys were having a hard time, they couldn’t keep a job. The trouble was they’d start flaunting it and people would take offence. I’d tell them to keep it private. I sympathized with them… I studied books on homosexuality and I wanted to help them, so I hired them. The NYC officials said the play would harm the city and that they were not equipped to deal with it. What they meant was that they were afraid the gay boys would have taken over, but they were great! I’d take them home, two or three of them, to the country on weekends… even my mother loved them, they’d have a good time… make my mother hats… paint her nails… fix her hair… One boy, I’m telling you, he was the most gorgeous thing in an evening gown. Anyone can acquire homosexuality, there are variations of it, but I found out that the true-born homosexual has the soul of a female inside a male body. When the play opened it was a big hit, people were coming from New York and paying 50 or 60 dollars to get in. The audience loved it.

HUSTON AND LESTER: Who was your favorite male star?

WEST: Cary Grant. I put him in a picture. I liked him so much I put him in twice.

HUSTON AND LESTER: Female stars?

WEST: I don’t know, name some.

HUSTON AND LESTER: Harlow?

WEST: Schoolgirl sex, she was before me.

HUSTON AND LESTER: Monroe?

WEST: Same thing, schoolgirlish.

HUSTON AND LESTER: Ann-Margaret?

WEST: They can imitate me, but who can imitate Ann-Margaret?

HUSTON AND LESTER: What about W.C. Fields?

WEST: Well, I knew he was a clever man, a comedian. Universal wanted me to use him. I said fine. We started workin’ together but he started gettin’ envious because I wrote the thing. He asked if I’d mind him writing a few of his own scenes, and I said no as long as he didn’t go write anything for me. He was plottin’ though. He’d hold up the shooting on the scenes he’d written and you see they’d be vital to the story. Among other things he wanted the billing to read, “Mae West and W.C. Fields,” instead of “Mae West with W.C. Fields.”

I’d have a little writing to do here and there, so he’d work mostly in the in the mornings. I’d come in after lunch… it was easier to for me to work in the afternoons. But he’d be late, or he’d delay shooting the scenes. He knew all the time he was doin’. The director came to me one day and said that Bill was on the sound stage, and that he’d been drinking. I said if he’s been drinking let’s get him out of here for the rest of the day. I had to go down to work, and I saw him there, showing off in front of about two hundred extras. The director told him, “Tomorrow morning, Bill,” so he left. Tipped his hat to me on the way out. He was humorous, maybe. We didn’t talk too often. When you’re a star, you don’t get much time for conversation, unless it’s part of a scene.

HUSTON AND LESTER: How did you get on with your directors?

WEST: A director can’t really tell me what to do. I look a certain way, and move a certain way, and talk a certain way… other actors have to move around me.

HUSTON AND LESTER: Is this the reason you’re a star?

WEST: Of course.

HUSTON AND LESTER: Do you play the piano?

WEST: I used to play a little boogie woogie. I play the drums, throw up the sticks and all. I did a lot of tricks like that, but I never fitted drums into the picture.

HUSTON AND LESTER: Do you travel?

WEST: I don’t like traveling, it’s work for me.

HUSTON AND LESTER: Do you intend to go on working?

WEST: I think I must. My fans love me. They holler in the streets and ask me for my autograph when I go out in my car. It’s the young crowd that like me. They write begging for me to work. Maybe I’ll do Diamond Lil again… in color.

THIS INTERVIEW INTIALLY APPEARED IN THE DECEMBER 1974 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.