Papal Studies with Nanni Moretti

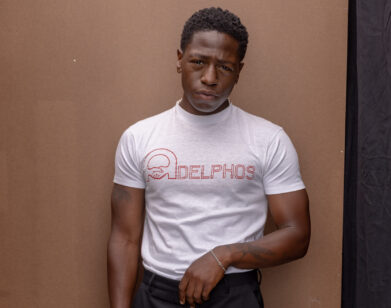

NANNI MORETTI (LEFT) WITH RENATO SCARPA IN WE HAVE A POPE.

What happens if the Pope isn’t ready to become Pope? That is the basis for Nanni Moretti’s We Have a Pope, in which the newly elected Cardinal Melville (Michel Piccoli) refuses to step up to the Vatican podium to address his people. Scrambling to save face, Vatican suits think outside the box and bring in a psychoanalyst (played by Moretti) to convince the new Pope he is the right man for the position. But when Cardinal Melville escapes, the church is left in a tailspin over what to do in his absence.

Interview spoke with Moretti about the filmmaking process, working with the legendary Michel Piccoli, and his upcoming gig as president of the jury at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival.

CRAIG HUBERT: When you begin a film, what do you start with? Do you begin with a character, an image, or maybe a scene?

NANNI MORETTI: I don’t know if there is always the same way of doing it. For The Son’s Room (2001) the first idea was for a psychoanalyst, who spends his time caring for other people’s problems, to have happen the most terrible thing, which is losing a child. That was the first idea. For We Have a Pope, the first thing was an image—the image of me, in a robe, as a priest. On other occasions, in other films, I had characters in mind and situations in mind that I just started writing down and putting together. On this film, I had an image of the newly-elected Pope having to take those first few steps to the balcony to greet the world and his inability to take those steps. I would say, for me, making a film is a piece of life, in all senses. Therefore, some time has to pass between freeing myself from the film I just made and charging myself up for the new film I’m working on. In that period, a sentiment or feeling is formed—with regards to others, with regards to society, and with regards to myself, which is almost always negative. [laughs] This feeling starts to become a story, and the story sometimes calls for one style or another style. So even when my films aren’t about me directly, they’re in some way autobiographical. They reflect me.

HUBERT: You mentioned the time between films, how you have to let go of one before you take hold of another. Has this always been the case, or something that has developed over your career?

MORETTI: This is a good question. Now, I would like that period of time between films to be shorter, and it’s not that I want to give a tragic feel to this interview, but I have less time ahead of me. [laughs] But in the beginning, this period of time between films was shorter. Two new things came into play. One, I started to become more well-known, therefore the period of anticipation came to be bigger; it shouldn’t paralyze us, but it’s there. And then other things started to happen: I became a producer, I opened my own cinema, then directed the Torino Film Festival for a couple of years. These are all things I do not because I have to but because they are pleasing to me. Not like a mission. Since I feel lucky, I feel like I should share some of the good fortune I have.

HUBERT: Why a film about the Pope now? Was this something you had in your head for a long time, or was it born out of the recent controversies surrounding the Vatican?

MORETTI: No, no, neither one or the other. There’s a part of me in the psychoanalyst and the difficulties the Pope has. I wanted to talk about a man who just can’t do it anymore, that has a great responsibility and great power. This man is unable to fulfill his responsibility to represent all people because that would mean cancelling out his own personal vulnerability. So he gives precedence to his own personal venerability over this vocation to represent everyone.

HUBERT: You mentioned the image of the balcony earlier, and I was curious if you were thinking of the connections between the role of the Pope and the role of an actor.

MORETTI: Yes, but this analogy wasn’t done purposefully in the beginning. After seeing the film, I noticed this, not symmetry, but analogy between the balcony and the stage, between religious representation and theatrical representation. Often a director isn’t conscious of why every decision is being made. But I don’t thing I chose consciously to make this connection between the church and theater. But I wanted this character to have some kind of desire within him that he hadn’t been able to realize; in this case, it was to be an actor.

HUBERT: I wanted to ask about Michel Piccoli, and if there was anything specific that made you think he would be the right choice to play the Pope?

MORETTI: He was the first idea that I had for the role. It didn’t condition the writing of the screenplay; in fact, I contacted him after writing the first draft. There was one problem: I absolutely did not want to dub the film, but I wanted to film in Italian. I wasn’t sure he could in an entire film in a language that wasn’t his own, so I asked him if he would audition, as if he was a 20-year-old debutante, and he said yes. I sent him six scenes, which he memorized, and that is what he auditioned with. I like actors who are talented at portraying a role but don’t lose themselves in portraying that role, who don’t forget they are actors portraying a role. Therefore they show me their talent as an actor and their truth as a person. Michel Piccoli is one of those actors.

HUBERT: You’re also the president of the jury at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, where this film screened last year and where you won the Palme d’Or in 2001 for The Son’s Room. What are you thinking about going in?

MORETTI: It’s something that pleases me very much. I was on the jury at Cannes 15 years ago and I had some really nice meetings with the other jurors—in particular, Tim Burton and Mira Sorvino. As for the process, the juror’s choices are never conditioned by any outside factors—the directors of the festival, the public, or the reactions of the press. Every juror has a singular taste, and there are dynamics created between the jurors, but in my opinion, it’s wrong to search for a unanimous vote. In the case of a unanimous vote, the average, middle-of-the-road film is chosen, the film that doesn’t hurt anyone. In order to please everyone and agree on a unanimous vote, there isn’t anybody who is incredibly happy about the movie. I think it’s wrong to choose the film that isn’t displeasing to anyone. It’s important that the film that is rewarded is most pleasing to the majority of the jurors; if that’s not everyone, that’s all right. The important thing is to evaluate every film with the same amount of attention and without prejudice. And then we vote. [laughs]

WE HAVE A POPE IS OUT IN LIMITED RELEASE FRIDAY, APRIL 6.