More Than Human? Mitch McCabe

PHOTO BY BRAD WALSH

The most compelling subject in Youth Knows No Pain (2009), a documentary about the American anti-aging industry, is Mitch McCabe, the filmmaker and narrator. The daughter of a plastic surgeon, McCabe uses her lifelong issues with aging and mortality as a jumping off point from which to explore our nation’s fraught relationship with plastic surgery, anti-aging creams, and beauty treatments. “I’m a great target for the American anti-aging industry,” McCabe narrates at the beginning of the film. “Single, no children, with maybe a little bit of fear of my ticking biological clock.” By turning the lens inward, to a place that is uncannily familiar to many women, the film is less of a preachy exposé of plastic surgery and celebrity culture, and more of a tender, albeit suspicious exploration of the American search for the Fountain of Youth.

I spoke to McCabe right before she embarked on a trip to publicize the DVD release of the documentary, which premiered as part of the HBO documentary film series in 2009. I was eager to speak to the woman who had admitted on film that, despite her $30,000-a-year temp salary and $68,000 in debt, she still spent $200 every six weeks on getting her gray hairs covered, a habit that she wouldn’t give up, even if it meant losing her healthcare.

We opened our conversation with a discussion of how McCabe chose her subjects. While the list includes some celebrity names, including Julia Allison, Simon Doonan and Linda Wells, the editor-in-chief of Allure, the most riveting characters to watch are those that McCabe found through casting calls on sites like Craigslist. They include Sherry Mecom, a woman in her mid-50s from Texas who enters the film timidly, explaining that she took care to make sure that her outfit matched and scoffing when McCabe suggests that she looks good. “I used to have three or four boyfriends at one time, one on each arm,” Sherry says, twisting in her chair. “And then one day, you look up, and all those guys aren’t running after you, and you’re not getting the catcalls when you walk down the street. Hello! That’s no fun.”

A year later, McCabe returns to Texas to interview Sherry at her home, and finds a person transformed. The timid Sherry from the original casting call has been replaced by an exuberant one that twirls around in a white halter dress, proudly showing off the improvements made not only to her physical body, but also to her home. Sherry admits that in the past year, she’s spent $35,000 on aesthetic procedures, and it’s clear that all of the work she’s had done has lifted her mood. But when McCabe revists her for the third and final time in the film, she finds that Sherry seems to be sliding into depression. The change is reflected in a weight gain that has left her almost unrecognizable. As if to signal defeat, she offers the white dress she wore in earlier scenes to McCabe, telling her that it no longer fits.

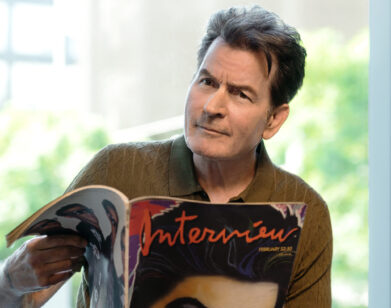

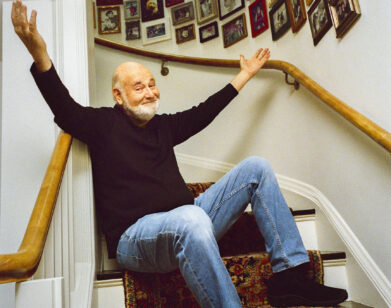

In the past, most of the burden of explaining the anti-aging industry has fallen on women, who are often characterized as being enslaved by the cult of beauty. However, McCabe is careful to point out that men are far from immune to it. She spends an almost equal time interviewing males as she does females in the movie, including Norman Dessing, whose $50,000 quest to look like Jack Nicholson results in a look that is less The Passenger and more The Shining, and Gary Baldassarre, a hair transplant aficionado who turns his self hatred outward by viciously criticizing the physical appearance of female politicians and pundits as he watches the evening news. “Men’s issues are a little bit different,” McCabe explained to me. “Women are afraid of being alone, but men are cognizant of their approaching death. Their time is ticking, and they see in their physical presence the ultimate proof of their mortality.” If for nothing else (and there are plenty of other reasons to buy the film), the documentary is worth watching to see the refreshing shift of focus from the female to male perspective.

So why does youth fetishization, especially as depicted in Youth Knows No Pain, seem like such an American trait? “Because unlike many Europeans, we don’t have a system of government pensions,” McCabe reasoned. “People need to work for longer, and studies are revealing that in order to find jobs, workers need to appear to be youthful.” If an argument can be cobbled together supporting the resuscitation of Social Security using the anti-aging industry as an economic red flag, then the kernels for debate may lie in McCabe’s documentary.