Michael Winterbottom’s American Psycho

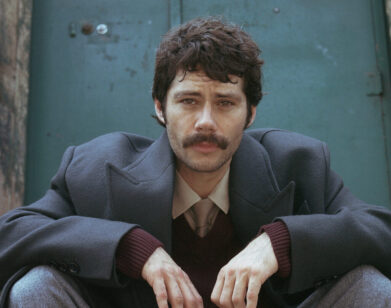

CASEY AFFLECK IN THE KILLER INSIDE ME

Acclaimed British director Michael Winterbottom is no stranger to challenging and heady subject matter (9 Songs, 24 Hour Party People). Nevertheless, for his first American film, he chose to adapt one of the more delectably vicious, landmark novels in the annals of American noir, Jim Thompson’s The Killer Inside Me. Excuse the pun, ma’m, but Winterbottom killed it. That is to say, he has crafted an entertaining and brilliant psychological portrait of a charming sociopath that is every bit the 2010 answer to Mary Harron’s American Psycho. In a career-defining lead performance, Casey Affleck plays Lou Ford, a young deputy sheriff in 1950s Texas who masks homicidal tendencies and paranoia behind an endless supply of local-yokel bon mots and his small town’s mundanity. But a fiery encounter with a local prostitute named Joyce (Jessica Alba) ticks off a Freudian kettle inside his disturbed mind; soon, Ford’s amusingly pathological whoppers are outmatched by his sexual, murderous destruction. When it premiered at Sundance this year, The Killer Inside Me sparked a curious controversy over what are, admittedly, two extremely graphic acts of violence. In our interview with Winterbottom, he emphasized that not only is his film faithful to its 1952 source material, but Thompson pushed the boundaries even further…more than half a century ago.

HUNTER STEPHENSON: The film impressed me more than any other at the Tribeca Film Festival this year. I was surprised by how true it remained to Jim Thompson’s novel. When did you first read the novel and what was your first impression?

MICHAEL WINTERBOTTOM: Thanks. Well, I had read some work by Thompson before, but I hadn’t read The Killer Inside Me until about two years ago. I had been trying to make a film in England–it was a modern film set close to the present. We tried to borrow a little bit from a book by David Goodis, an American noir writer in the ’50s, but we ran into copyright issues and couldn’t make it. So, I read The Killer Inside Me and I thought it would be great to make it as faithfully as possible. You can almost take the book and use it as a script. And we used a lot of dialogue from the book. Thompson has great dialogue and he’s also a great storyteller. You know, The Killer Inside Me is a very lean book, and I really like how, by page seven, Lou has met Joyce, and he’s been hit by her, he’s hit her, fucked her, and he’s in love with her. It’s quite a good start.

STEPHENSON: For a book published in 1952, its descriptions of violence and sex are still incredibly provocative, no?

WINTERBOTTOM: I think it is very surprising how shocking something can be that was written then. Obviously, Thompson’s depiction of this small town in Texas, there’s a sense of “Oh my god, regular people are having crazy sex.” And the funny thing is, there is more adventurous sex in the book than in the film. We’re more constrained now in the cinema than he was then in the novel. It’s really weird, actually. Recently, I’ve been reading a book by an author called Eric Ambrose, published in 1939. It’s a detective noir set in Europe. It’s full of heroin smuggling and prostitution rings, and it just reminds that people behaved like this years ago. And, you know, they always have.

STEPHENSON: You’ve made several well-regarded films that are politically-oriented. And here’s Lou Ford: An authoritative cowboy-type from Texas with considerable daddy issues and a penchant for mind-numbing small talk. And a gross capacity for violence. Did the character remind you of anyone?

WINTERBOTTOM: [Laughs] He’s not George W. Bush. But, Lou does have a lot of father issues…

STEPHENSON: He lives in his father’s shadow and lives in his house, and sits in his chair…

WINTERBOTTOM: Yeah. See, I wanted all of this to be more clear in the film than perhaps it is. Lou lives in his dad’s house, like you said. And he reads his dad’s books, he sits in his study. He feels totally inadequate to his father and also hates his father. So, [the ending of the film] is a final catharsis. The father aspect is a really big element of the character and the story, and there are several other father figures knocking around within the story as well. But really it is about a young, violent Texan with a lot of father issues–and it’s very much set where George Bush is from–but it’s not about George Bush. Clearly, Jim Thompson wasn’t writing about him! But that culture, the fact that people are like that, you know? Thompson was writing about a time, a place and people he knew very well. He knew a lot of what went on firsthand. But I think the book and the film are about how fucked up people are everywhere and how people mess up and destroy their lives. It’s like Hamlet or Macbeth in that way.

STEPHENSON: At my screening, I think I was smiling for most of the time Casey was on screen. The film is very funny.

WINTERBOTTOM: Good, that’s good.

STEPHENSON: How important was it for you to have the comedy connect with viewers?

WINTERBOTTOM: It’s a difficult area, you know? I didn’t want to make it too spoofy, but the comedy is very true to the book. Both the film and the book have these moments were you are aware of the gap between what Lou thinks is happening and what is going on. And the gap between how he is behaving and what he is thinking. So, there is that, in terms of humor, but I wanted to avoid doing it in a way where it would be too post-modern, because then it’s all a joke. The story is no longer serious, or even a story, really. It’s a similar thing with the music in the film. I think a lot of the [country] music from that period has a very lighthearted, funny tone to it. But so often they’re talking about a man killing another or having an affair or something.

STEPHENSON: How do Joyce [Jessica Alba] and Amy [Kate Hudson] use sex differently in the film? The majority of their scenes are in bed with Lou, and rather intense.

WINTERBOTTOM: Well, one thing Thompson does well is he takes the usual good girl-bad girl thing in noir and really changes it. And he says, okay, in this story, Joyce, who’s the whore, also loves Lou, and Amy is the good girl who is sexually bold. The first time we meet Amy in the book, there’s more of that, she’s naked. So, the girls are similar. I think you can almost imagine one as the other one. It’s very provocative in that way. Part of the story is that it’s a love story, and both of these girls love Lou and that’s why he has to kill them. What he does to them is so hateful, so pointless, brutal, and horrible because of his self-loathing. And of course, the sexual abuse is sparked with Joyce, but the film doesn’t mean to say that women who like to be slapped making love want to be killed. [Laughs] Sex triggers Lou’s craziness.

STEPHENSON: There are numerous sex scenes. After making 9 Songs, was it a creative decision not to include female nudity? I was puzzled a bit. We see a head bashed in, but no breasts.

WINTERBOTTOM: That was in the contract. You know, I do see what you mean. And I hope that, in a sense, we can get away with it because it’s the 1950s, therefore, we don’t normally associate 1950s films with that. But there’s a lot of ridiculous hypocrisy about sex in films today. And that’s one of the reasons why I made 9 Songs, to say, “Why can’t you put sex in a film?” But I don’t think Kate and Jessica would be particularly happy to do a 9 Songs version of The Killer Inside Me. [Laughs]