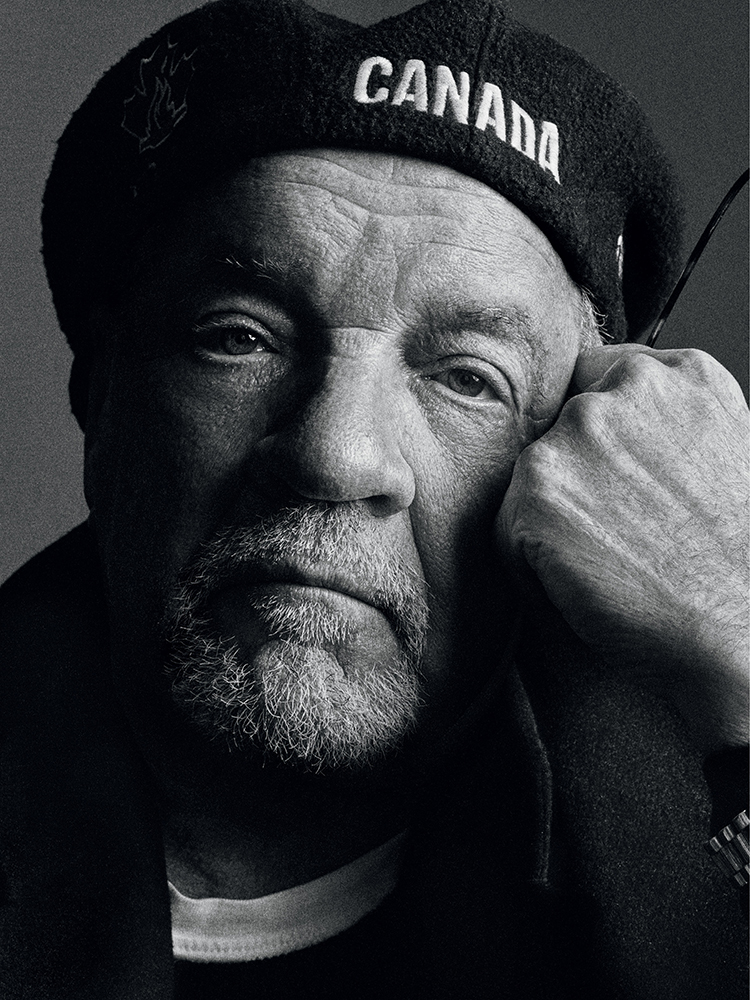

Paul Schrader tells Nicolas Cage why First Reformed is his masterpiece

It was 1972. Paul Schrader was 26 years old and in a free fall. The film critic and fledgling screenwriter had been living in his car, drifting aimlessly through Los Angeles, alienated from everyone he loved. After an ulcer landed him in the hospital, his choice—between productivity or entropy—became clear. Schrader chose to write, and about two weeks later had completed a script about a nocturnal loner who stalks the streets of New York in his yellow cab with fantasies of one day cleansing the city of its depravity. It was called Taxi Driver (1976) and, with the help of director Martin Scorsese and star Robert De Niro, made Schrader a household name in Hollywood.

The success of Taxi Driver (it was nominated for four Academy Awards including Best Picture) gave Schrader enough studio clout to eventually direct his own films, which he first did with Blue Collar (1978), a searing look at the American working class. He reached a career highpoint in 1980 when he wrote and directed American Gigolo, which featured a star-making performance by Richard Gere as a male escort, and reteamed with Scorsese and De Niro for the unflinching boxing saga Raging Bull, widely considered one of the greatest American films ever made. Schrader, who has a master’s degree in film studies from UCLA, spent the next three decades burnishing his reputation as an intellectual and risk-taking filmmaker with projects such as Light Sleeper (1992) and Affliction (1997). He made idiosyncratic and often violent movies about self-destructive outsiders and deviants seeking purpose or redemption in an indifferent world—with mixed results. (For every Taxi Driver, there was The Canyons.)

Schrader’s latest film, First Reformed, is a return to form. Borrowing elements from his Calvinist upbringing and the European cinema that, as a young man, introduced him to a world beyond the church, the movie stars Ethan Hawke as the Reverend Ernst Toller, a former military chaplain shattered by the death of his son during the Iraq War. When Toller meets the environmental extremist Michael (Philip Ettinger) and his pregnant wife Mary (Amanda Seyfried), he becomes obsessed with saving a world he believes is destined for destruction. Ahead of its release, Schrader spoke with his friend and frequent collaborator Nicolas Cage about why First Reformed might just be the culmination of his life’s work.

NICOLAS CAGE: Listen, I want to congratulate you on First Reformed. I couldn’t help thinking that all roads have probably led to this moment. It is, in fact, your magnum opus.

PAUL SCHRADER: I think so. It brings a lot of stuff together. Before I became a screenwriter, I wrote a book on spiritual film called Transcendental Style in Film—that was my entrance into this world. Then the first script I wrote was Taxi Driver. This film harks back to both of those things. So now I have an intimidating sense of resolution because I’m not quite sure what to do now. I hope this isn’t my last film, but if it is, it’s a pretty good last film.

CAGE: I’m glad you brought up Transcendental Style because there is a part in it that talks about transcendence and immanence in Robert Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest, which I thought collided beautifully in First Reformed—immanence in terms of Ethan’s natural and powerful internal performance, and transcendence in terms of how it transported me to another dimension. I couldn’t help thinking, while I was watching the movie, about the Earth itself being the Holy Grail fortified by the blood of Christ in the soil, and how it’s being destroyed by large industry. Global warming is an element in First Reformed. Are you activated in your own life about this issue?

SCHRADER: We have chosen, more or less, not to sacrifice our present lifestyle for the lives of our children. There’s not much we can do about that. You and I have lived in the sweet spot of history: the baby boom, the least amount of war, the most leisure time, the most education, the best diet, the best health. And what did we do with all of those great moments in history? We got greedy. We ruined it for our grandchildren. So if the generation before us was the greatest generation, we are the most selfish. What I found interesting in doing this film is, you have a man, Reverend Toller, who is sick—he has what Kierkegaard called “the sickness unto death,” which is despair. And he’s trying to fix it somehow, either through the rituals of the church or through alcohol or keeping a journal. And then he comes across this boy, who is also in despair, and he fails to help the boy, but then he catches the boy’s “virus,” which I found so interesting. Was he an environmentalist all along, or was he just looking for an excuse to enable his death trip?

CAGE: That said, there are some seriously funny moments in the movie between Cedric the Entertainer and Ethan Hawke, while they’re composing a song in, I think, an outhouse. Was that something that was in the script all along, or was that Cedric putting his own spin on it?

SCHRADER: Oh no, that’s something I had already written. It’s so risky portraying church leaders, because we think so little of them. We have so many prejudices against them, and it’s very easy to make them two-dimensional. One of the reasons I got a black entertainer was to get out from that bias against a serious white actor. It would automatically turn him into Pat Robertson. And, of course, Cedric has such a great smile. If you’re out with him in public, you see people’s faces light up when they see him.

CAGE: I also couldn’t help but think, given your Calvinist upbringing, that this movie is very autobiographical. I know you once famously said that, with Taxi Driver, you were in the same headspace as Travis Bickle when you were writing the screenplay, and I did see a Taxi Driver element in Ethan’s performance. Given that you were raised in that background—I think at one point you considered becoming a pastor—were the writings that Reverend Toller puts in the diary close to some of your own thoughts?

SCHRADER: I did, as a kid, go door to door. I did proselytize, and I realized I couldn’t be a minister because I just didn’t get along with people. Then I thought I’d be a lawyer, and I realized I couldn’t be a lawyer because I didn’t get along with people. The only thing left for me was to become an artist.

CAGE: But growing up, you didn’t have many movies in your household, no television, nothing. For a very long time, you hadn’t ever seen a motion picture.

SCHRADER: There was a church proscription done in the 1920s that forbade movie theater attendance, along with another whole set of what they called “worldly amusements.” That was still enforced when I was a kid, so I didn’t see films. That’s not such a bad thing, because I was raised around the oral tradition, where people told stories and jokes. That’s how you entertained, and that’s better than watching television or being on the internet. The first films that really caught me came from European cinema of the ’60s, when I was in college. There was a little softcore porn theater in Grand Rapids that was going out of business, and the owner thought that since it was near the college, he could make some money by having an Ingmar Bergman festival.

CAGE: Having an intellectual perception of a man’s entertainment, as opposed to a child’s, separated you from your colleagues. The disadvantage from an intellectual standpoint was that you did not have an emotional association to movies, and that was a damning curse. Pauline Kael even wrote that Patty Hearst [1988] is the work of a brilliant filmmaker who lacks the ability to make the audience feel. For the record, I don’t agree with her. I think your movies are cold, but they’re a beautiful cold, like blue ice, and they make me feel so much. First Reformed has a powerful, emotional ending, and I was in tears.

SCHRADER: You know, they say that we always love the music we heard when we first fell in love, and the same thing is true about movies. We always love the movies we were watching when we first fell in love with movies. And for me, that was a kind of serious cinema. Now, for Marty [Scorsese] or Steven [Spielberg] or George [Lucas], they fell in love as kids with genre films, so it is a different experience.

CAGE: Your mother said no to television because she thought it would destroy the family unit, and you agreed with her—is that right?

SCHRADER: It’s interesting, because television is what ultimately broke down walls in that closed community, because we couldn’t keep television out. The day it changed for me came when we lived on the west side of town, in an area that had a lot of Polish Catholics. My mother went out looking for my brother and me, and she found us down the block in a neighbor’s house watching after-school television. And there was a Madonna on top of the TV. That just about tore it for my mother. It wasn’t so bad that we were watching TV, but that we were watching TV in a Catholic house with a Madonna on top of the TV. She went right home and told my father that we were going to have to get a TV of our own so that we didn’t have to watch it down the block.

CAGE: That’s how I feel about the iPad today—I have seen the destructive effects that it’s had on the family unit. You said that Taxi Driver was the first script you wrote, but I thought The Yakuza was the first one you wrote, with your brother Leonard in 1974.

SCHRADER: Yeah, Taxi Driver I wrote as a kind of therapy, and then about a year later, I had the idea to work with my brother on The Yakuza, and Taxi Driver sat in a drawer. And then we all had some success: De Niro got an Oscar for The Godfather Part II [1974], Marty had a hit with Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore [1975], Michael and Julia Phillips got an Oscar for The Sting [1973], and I sold a big script. Suddenly Taxi Driver—that little movie that nobody wanted to make—became a viable option for Columbia Pictures.

CAGE: And now it’s cited as one of the greatest films of all time. You’re on record saying, “It doesn’t really matter what I do, the first line of my obituary will be, ‘The writer of Taxi Driver.’” Where were you going with that?

SCHRADER: Well, if you read obituaries, and I’m sure you do, you sort of get the lingo. I’m not quite sure what the first line of yours will be, but I think mine will be about Taxi Driver.

CAGE: Do you remember how we met? I’m a little confused about the timeline myself. Did I speak to you on the phone from the Beverly Hills Hotel?

SCHRADER: I think the first time we met I was visiting Francis Ford Coppola on the set of Peggy Sue Got Married [1986], north of San Francisco, where you were shooting.

CAGE: Near Petaluma.

SCHRADER: I went up to Petaluma to see him about something, I forget what it was, and he introduced us—just a casual introduction. But then the next time was when Marty got into preproduction on Bringing Out the Dead [1999].

CAGE: You came over to the house, and you said a couple of interesting things to me over dinner. I think Marty was hoping you would give me some guidance. You said to me, “Do not throw your pearls before swine,” in terms of not giving away all the tricks of my performance, but you also said something which has stayed with me ever since. You said that characters that raise more questions than answers have a longer shelf life, and that is no more prevalent anywhere than in Ethan’s remarkable performance in First Reformed. The other thing that really emerges is one of your most powerful signature elements: the idea of a man in his room. Can you speak a little bit about that?

SCHRADER: I know exactly where that came from. When I was a film student at UCLA—I was in film studies, not filmmaking—I was living in a house with a group of students who were doing a biker movie. And I thought to myself, “I would never want to be a filmmaker—I’m not like them. I want to be a critic.” And then when I was reviewing films for The L.A. Free Press, I saw Pickpocket [1959] by Robert Bresson. It’s about this guy who sits in his room and writes a journal, then he goes out and commits petty crimes, and then he goes back and sits in his room and writes some more. I thought to myself, “I could make a movie like that.” I don’t want to make this biker film, but I can make a movie about this guy who sits in his room and writes in a journal. And then about two years later, I wrote Taxi Driver. So it’s certainly something that’s become part of my creative DNA.

CAGE: You followed Taxi Driver by directing your first film, Blue Collar, in 1978, which stars Harvey Keitel, Yaphet Kotto, and Richard Pryor. There were some pretty hot moments on that set as I recall.

SCHRADER: I had a volatile group of actors, and Richard was afraid that he was going to be the sidekick to Harvey, and Harvey was afraid he was going to be Ed McMahon to Richard’s Johnny Carson. And Yaphet was afraid that they were both going to cut him out. So it was three animals fighting for the same turf. And it didn’t take very long before that came out. Unfortunately, because the subject of the film was race, that’s how it came out. It’s one thing to have arguments on set, but when they got tense with race, it was very angry and hurtful. I remember one day Richard said to me, “The first white male I ever met came to my mother’s door to fuck her, and you’re just like him.” At that point, you kind of scratch your head. You don’t quite know what to do with that information.

CAGE: I read a book a million years ago called Poésies by Isidore Ducasse in which he puts forth the notion that the critic is more important than the artist, because the art is looking for a response, and the critic provides that response. You are probably one of two filmmakers, along with Jean-Luc Godard, who went from film commentary into actual filmmaking. What do you think about the state of film criticism today?

SCHRADER: I’m still a film critic, but I do think that film criticism and filmmaking are inherently incompatible because one wants to know why a thing lived or died, and the other wants to have that thing born. So if you let the critic—the medical examining critic—into the birthing room, he will kill that baby. You have to be very careful that you don’t let the critic in you get near the creative mystery. And that is always a struggle. I don’t know if I’ve said it to you, but I know I’ve said it to many actors: “I don’t know why he says this, and I’m not quite sure what it means, but I know he says it.” And you have to maintain that kind of respect for the mystery. Otherwise you get high-bombed by your own overthinking.

CAGE: That is great counsel for young filmmakers who read this interview. Paul, thank you so much for an enlightening and compelling interview. I enjoyed our conversation.

NICOLAS CAGE IS AN ACADEMY AWARD–WINNING ACTOR, AS WELL AS A DIRECTOR AND PRODUCER.