The Extreme Sports Roulette

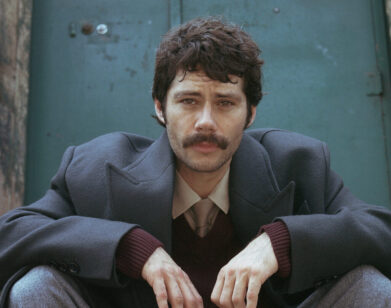

On December 31, 2009, one month before the 2010 Winter Olympics, 22-year-old Kevin Pearce hit his head in a snowboarding accident. Pearce was practicing his “cab double cork” flip. Affable and gregarious, he’d recently started beating his friend-turned-rival Shawn White and was being touted as a top contender on the US Olympic team. At the top of the half-pipe, Pearce and his friends—a group of eight professional snowboarders who called themselves the “Frends” crew—played rock, paper, scissors to see who would go down the half-pipe first. Pearce lost.

To describe Lucy Walker’s film The Crash Reel as affecting is an understatement. In the aftermath of his accident, Pearce, his three older brothers, and his parents open their lives up to the camera. Walker tracks his recovery to a soundtrack of Moby, Lykke Li, and Sigur Rós. Since the Oscar-nominated director began filming The Crash Reel, many of the athletes who appear in the film have been severely injured. More than one has died. It is Pearce’s incredibly close-knit family, however, that anchors the film—especially his brother David, who eloquently explains his feelings about living with Down Syndrome. “Their philosophy in parenting and family is such a beautiful one,” says Walker of Pearce’s parents. “They have this idea, ‘You should tell people how you feel.’ Not what to do, but tell them how you feel,” she continues. “The world would be revolutionized if we learned that simple trick of telling people not what they should and shouldn’t do, but how we feel about what they’re doing.”

The Crash Reel debuted at Sundance in January and was recently shortlisted for the Oscar Documentaries shortlist. This Friday, it comes out in theaters.

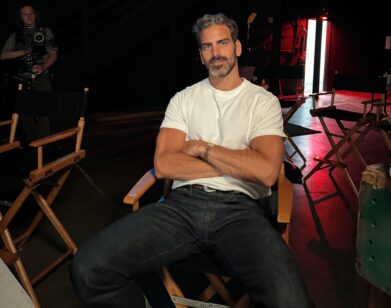

EMMA BROWN: How long after meeting Kevin did you decide that you wanted to make a documentary about him?

LUCY WALKER: [laughs] About five minutes.

BROWN: Really?

WALKER: Yeah. I met him right after he was injured—I didn’t meet him before. My first thought was how, “Oh, how sad to go from Olympic hopeful to Traumatic Brain Injury survivor.” Then I realized that it wasn’t over at all; he was absolutely determined to get back into snowboarding, even if the doctors were telling him that it would kill him if he hit his head. I also realized what a character he was and his family was. I’d had ideas about making similar films about injured athletes or about extreme sports—I’d actually gone to this extreme sports retreat thinking that there might be a movie in the world of extreme sports. I was at the retreat when I met him. But five minutes after I met him, I thought: “This is an amazing movie, and I want to make it.”

BROWN: There have been a few articles about brain injuries in mainstream sports like football and hockey over the past few years.

WALKER: I think we’ve reached that point where we understand medically what we are doing to ourselves with these sports. In football, it’s kind of hard to get the access that you want for the story and, of course, it’s very long-term: the effects of the repeat concussions really don’t hit until decades afterwards, whereas the traumatic injuries in extreme sports are very immediate. I realized Traumatic Brain Injury was a fascinating and important story that not had been told very much. I wanted to know more.

BROWN: How do you ask someone to let you into all aspects of their life for several years?

WALKER: I can ask, but people have got to have that gift: that courage and that talent for opening their lives to the camera. Being candid is a gift, and that’s what the audience responds to. Part of it is me asking, and part of it is just their inherent talent, which is what you are looking for when you make documentaries—people that are really going to let you in on what they are going through.

BROWN: When you started the documentary, did you think that Kevin would return to professional snowboarding?

WALKER: I wasn’t sure. I didn’t know, and I didn’t know making it. I think that’s the source of the drama. I’m very happy that it’s worked out this way. Kevin is a true inspiration, and I think his recovery couldn’t have gone better.

BROWN: One of the people who pops up throughout the film is freestyle skier Sarah Burke, who died last year from a skiing injury.

WALKER: That happened during the making of the movie. We wanted to pay tribute to her. We were very saddened by that.

BROWN: Do you think that there is a way to prevent these accidents from happening?

WALKER: No. Accidents will happen in this sport. It’s the terrible truth of any system, really. There’s a theory of accidents that I studied when I was making a film about nuclear weapons (Countdown to Zero, 2010): you can never eliminate accidents, because the measures you introduce to prevent accidents actually produce more accidents. That’s certainly true of this sport; you’re flying over 40 feet of what might look like snow, but it’s hard as ice, it’s as hard as pavement. You’re doing acrobatic spins and tricks, 40 feet above pavement, essentially. There’s been more accidents since, and there are going to continue to be more accidents, that’s the nature of the sport. The X-Games this year a snowmobile racer was killed, Caleb Moore. It’s interesting that nobody gives up. Caleb’s brother was also injured the same day that Caleb was killed, and his brother, Colton, has gone on to do even more dangerous tricks now.

The thing about Kevin’s group of friends, a couple of them had serious accidents while we were filming. One of them broke his neck very seriously in New Zealand training for this year’s Olympics, a similar set-up in the sense that he was pushing himself for the upcoming 2014 Olympics. He was attempting a new trick, he landed on his neck and broke it, and he was paralyzed for a short time. They managed to insert some of his hip bones into his throat, and he’s not paralyzed, but he’s going to have a long time learning to walk again, and he’s not going to be able to snowboard again, unfortunately. He was a medal contender, just like Kevin was in the last Olympics. That was Luke Mitrani—the really cute kid always doing flips. Luke’s older brother Jack, who is in the group, is injured out. Danny Davis is injured. There’s not many of them—there’s only one of them in that group left in, Scotty Lago, who was medaled in the last Olympics and is looking good for this year’s Olympics. It’s really shocking. I’m not an expert on how to configure the sport, but I can observe and say that accidents seem to be a part of it. The athletes are incredible, with the courage that they accept the risk of death, paralysis, and brain injury. These are really life-changing, life-threatening injuries, and the risk is extremely high.

BROWN: Kevin’s dad uses the word “addiction.” It seems so crazy that such a dangerous hobby is so glorified. When you hear about all of these injuries and deaths, you feel like they might as well be shooting up heroin.

WALKER: I did a movie about Mount Everest (Blindsight, 2006). At the time, the statistic was that one in 10 people that tried to climb Everest died trying. I thought, “My gosh we think of Everest summiters as heroes, but really it’s kind of not much safer than a round of Russian roulette.” Russian roulette is one in six people; Everest is one in 10 people. Why is nobody questioning the sanity or suicidal tendencies of Everest ascenders? It’s kind of a question of framing: How do you frame these activities? We frame them as freedom-loving, exciting, progressing sports and they are. But there are other ways to frame it. It’s also true that these young men, neurologists say that their frontal lobes aren’t developed yet—the long-term planning part of the brain. You could say teenagers are brain-injured. They feel they are invincible and that these things can’t happen to them, which is what Kevin was taught and why Kevin wanted to make the movie. He loves the sport, but he wanted to make the movie to make people aware that this was possible. He felt that he hadn’t realized that it was possible. So I think that you can ask loads of interesting questions, which is why it’s such a rich film and yet I love the sport. These athletes are so fun and so vibrant, and so infectiously vivacious and it’s just a joy and a thrill and a laugh to be around them. They are real life lovers. I sort of don’t judge them, for me as a slightly older person and a girl, I have a different perspective than young men about how to weigh the cost-benefit analysis of risky behaviors.

BROWN: Do you ski or snowboard?

WALKER: I must confess I’m a skier. I love skiing and do it any chance I get, but I find my edge in filmmaking, not in skiing. I try to really challenge myself and make the most excellent films I can, whereas with skiing, I’m perfectly content to be a very intermediate skier. I’m very happy cruising around on the blue runs.

THE CRASH REEL COMES OUT THIS FRIDAY, DECEMBER 13. FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT THE FILM’S WEBSITE. FOR MORE ON TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY, VISIT THE FILM’S “LOVE YOUR BRAIN” TRUST.