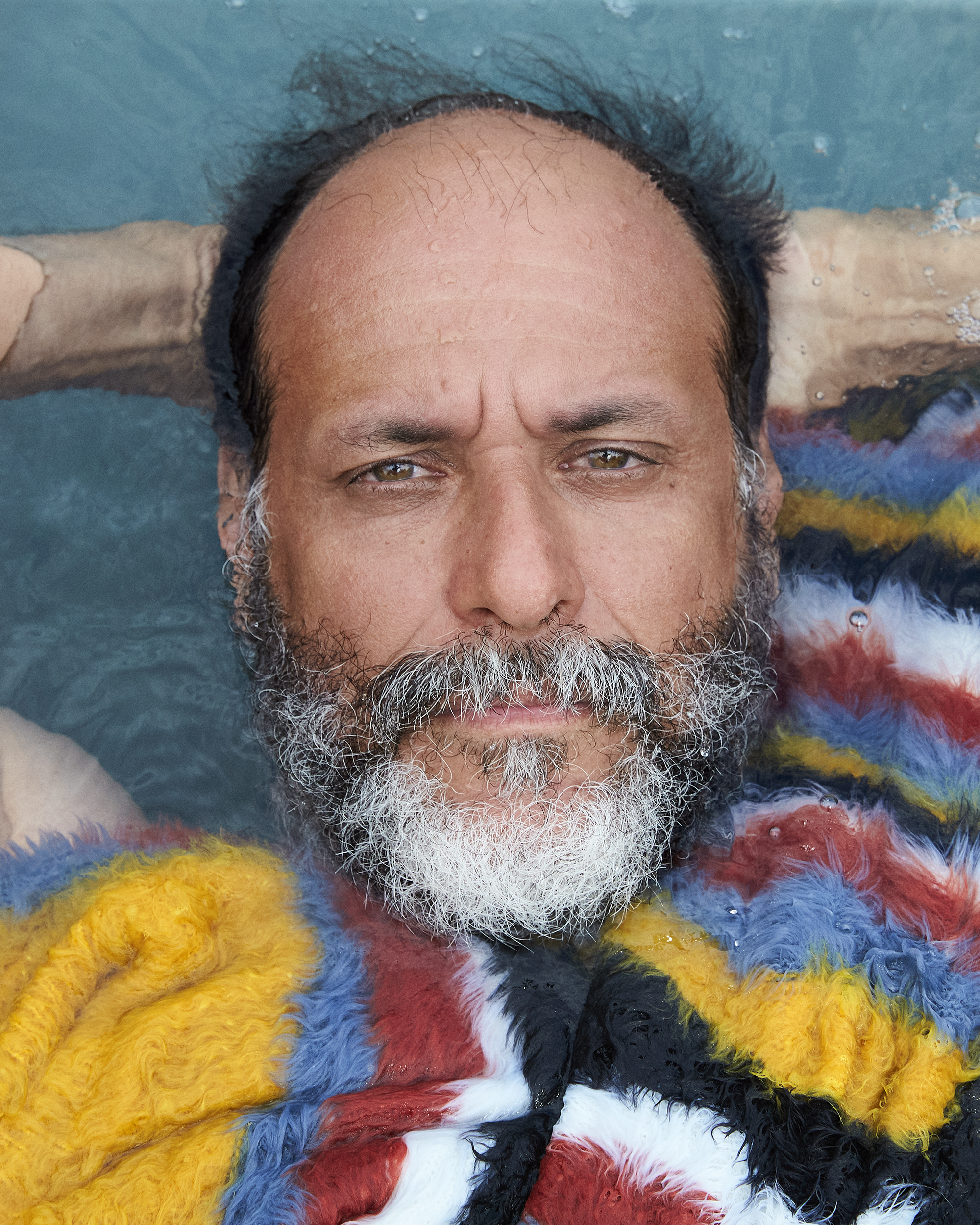

DIRECTOR

Luca Guadagnino and Jonathan Anderson on Disaster and Desire

Luca Guadagnino’s appetite for cinema has taken on mythic proportions, quite literally with Bones and All, a gory cannibal romance starring Timothée Chalamet and Taylor Russell, and in terms of his bursting slate of upcoming projects—projects that have everyone in town talking. Try to pass Luca a script (I did!) and you’ll be put on a years-long waitlist while he wraps up the Zendaya-starrer Challengers and works on the following, in no particular order: remakes of Scarface and The Lord of the Flies (in development), a dramatization of Scotty and the Secret History of Hollywood (optioned), an execution drama with Jennifer Lawrence called Burial Rites (unclear, sounds epic), a Call Me by Your Name sequel (in limbo but not dead), and an Audrey Hepburn something-or-other (never assume a biopic) with Rooney Mara. No stranger to keeping busy, fashion designer Jonathan Anderson is amiably jumping aboard the Luca train by designing costumes for the tennis world–set Challengers—an extracurricular from his day job designing six collections a year for his namesake JW Anderson brand, four collections for Loewe, plus jewelry, accessories, and an ongoing Uniqlo collaboration, while also directing campaigns and mounting fashion shows that stop time. But like his director, Anderson’s penchant for technological detachment and disappearing into forgotten worlds helps keep the tempest of capitalist overdrive at bay. Here, the two discuss America’s forgotten middle, failing upward, and how alienation can inspire something as universal as a love story. —PATRIK SANDBERG

———

JONATHAN ANDERSON: Hi Luca, how are you? I received the amazing tea set that you sent me.

GUADAGNINO: You like it?

ANDERSON: It’s very chic.

GUADAGNINO: It’s a bit daring of me because I don’t know your house and it might not look right for you.

ANDERSON: It’s going to look good under a painting. So here we are and I’m interviewing you. [Laughs] It’s a very strange thing to do because we’ve been hanging out a lot. So, Bones and All, I was watching it a couple of nights ago even though I’d already seen it with you in Boston. You made it in the U.S. What was it like filming in the American heartland?

GUADAGNINO: It’s a discovery, and as such, it’s thrilling. It gives a lot of revelations. You reshuffle your sense of place that you had in your mind through films and pictures. For instance, I realized that America, specifically the Midwest, is a place completely separated from the big metropolises. It’s a place where you see the effect of a dream, which could be considered the American Dream, that is completely different from the excesses of the dream acted out in a place like New York.

ANDERSON: Yeah.

GUADAGNINO: You see a different kind of excess. You see an excess of belief in this dream that is met with a disenfranchisement that is very hard. So in this sense, it’s very touching. The other thing I discovered is that America is huge, so you travel a lot, but it takes a long time for the landscape to change. I’m used to Italy or Europe where I travel for two hours and there is a very abrupt change in the landscape.

ANDERSON: Yeah.

GUADAGNINO: In America, you can drive for ten hours and the landscape remains the same, somehow. Then there is the experience of making a movie in America, which means that you have to make the movie under the ruling of America—the unions, the way in which they make movies there—which is a surprise. Sometimes it is a bitter surprise, and sometimes an interesting one.

ANDERSON: We spoke about this before, but what I loved, when I was rewatching the film at home, is that there is this—

GUADAGNINO: Did you like it again?

ANDERSON: I loved it. What I like in the film is that every so often you get the history of American image making in these very romantic portraits.

GUADAGNINO: Interesting.

ANDERSON: You’re watching the film and suddenly the landscape opens up and you have Timothée in a car, and you get this feeling of intimacy beside him. There’s this feeling that you are in the image. You are sympathizing with it, which brings me to the next question. What have you learned by being in America? At the same time, what do you sympathize with by making a film there?

GUADAGNINO: I learned that I have a vast curiosity and I can understand systems that are alien to me because of this curiosity. That was a beautiful revelation. I’m giving myself a compliment.

ANDERSON: [Laughs] It’s always good to compliment yourself.

GUADAGNINO: And the second part of the question was what excited me?

ANDERSON: No, what do you sympathize with now?

GUADAGNINO: That’s a great question. I sympathize very much with the outcome of the belief in the American Dream, as I saw it in small villages where we shot, where you could see that capitalism has left behind so many people. And yet, they truly believe in the values of capitalism, in a way which is almost blind, even if they are victims of that. But the open hearts they have were so wonderful, very touching.

ANDERSON: You’re amazing at portraying people on the fringe of society, or this idea of coming of age, or the awkwardness of being an outcast, ultimately. What draws you to that? What I always find in America, which I love, is that the kind of people that live on the periphery are more poetic somehow.

GUADAGNINO: It’s always about the idea that an adolescent is in a place they don’t understand, so there’s this idea of the outcast that is very strong in an adolescent that I resonate with, probably because I’m still the same person who wasn’t very at ease with himself. I’m still feeling that I’m at the back of the room, looking at the people in the center of the room enjoying their life, but I’m not participating. I feel empathy for those in that position.

ANDERSON: Why is cannibalism a compelling coming-of-age metaphor?

GUADAGNINO: When David Kajganich gave me the script for the movie, I didn’t want to read it because I was busy doing something else. I told him, “I can’t read it because I can’t consider it.” And he said to me, “Please.” My motto is, if someone asks you more than once, then you have to say yes. We have a theory about that, you and I.

ANDERSON: [Laughs] A very deep theory.

GUADAGNINO: Yes. I then read the script and loved it because I completely understood the characters. I loved the context, I loved the landscape, and I knew there was a wonderful love story. For me, the cannibalism was a condition. I believe there are people around the world that have this condition where they are driven by the urge every now and then to eat other people. But I did not think about it in an intellectual way. I thought about it in a narrative way. You know when you are at the end of a long day in the winter, in the house with your friends telling spooky stories, and you start to believe them? I’m like that. I believed in it. And after I started to show the movie to people, they began discussing the metaphor. I have yet to figure out what the metaphor is, unless we want to say it’s for the act of owning the person you love, totally.

ANDERSON: And then we get to the wonderful Timothée Chalamet. You kind of premiered him into the world with Call Me by Your Name. There is something that you do as a voyeur with a lens on him that is just magical. It’s very different from what I see in other performances from him. When I look at him through your lens, there’s something humane and relatable—a sensitivity. How has your relationship with him evolved?

GUADAGNINO: My experience of Timothée has always been one of a young boy, and then a young man, with incredible brightness and enormous ambition. Not just for the vanity of it, but as someone who could conceive of something that makes people turn their heads. That was also his attitude when we were doing Call Me by Your Name. He was unleashed. Also, he was very interested in the moviemaking process, not just his performance. And for him to be this gigantic movie star and still go to these dark or edgy places tells you how sophisticated he is.

ANDERSON: It’s quite remarkable in terms of where we are in today’s culture.

GUADAGNINO: Oh yes, given how people are terrified of saying anything that could be disturbing.

ANDERSON: Exactly. Then we move on to someone you introduced me to, who I am completely obsessed with, which is Taylor Russell. She’s one of the most magical people I’ve met and she’s going to be a superstar. Why did you cast her?

GUADAGNINO: I had seen her in a movie called Waves and I found her to be so incredible. First of all, she plays a 16 or 17-year-old girl in that movie, but was already 25 at the time. So there was something transformative about her. Her agent is my friend and I said, “Dani, I’d like to talk to your client, Taylor,” whom I didn’t know. And so they set up a conversation and when I started talking to her, I fell in love, because she had a demeanor that was so surprising—soft, tiny, sweet—and yet you knew that this young woman was made of steel, with an incredible will. Two days later I called her back and said, “If you want the role, it’s yours.” She was my first and last idea.

ANDERSON: She’s one of those people who, when you are talking to them, you are besieged by them, somehow. Her transformation in the film is crazy. Let’s talk about the music. You worked with Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, who composed the score.

GUADAGNINO: I should confess that I have a crush on both Trent and Atticus. They are fantastic and so beautifully delicate. These guys are Nine Inch Nails. They’re rock stars, and when you talk to them, you meet the most sensitive and thoughtful people. They encourage the process to be as radical as possible and they gave me a lot of trust in pushing the envelope, both of them, in different ways. They have a beautiful tenderness to them.

ANDERSON: The music never overcomplicates the image, which is quite hard to do.

GUADAGNINO: It’s very difficult. That’s why I was always skeptical about working with composers for cinema. I always felt they could overpower the movie and downsize the actual language of the film. But with them, you feel that they’re filmmakers as much as the rest of the people making the movie.

ANDERSON: You have portrayed many different versions of love on the screen. What is it about love that keeps you coming back? GUADAGNINO: Maybe because I’m a Leo, I need to embrace the world. I was thinking about this recently. To me it is very cinematic. There’s nothing more special than a face expressing turmoil. That’s what I love about it.

ANDERSON: From Call Me by Your Name to Suspiria, you’re a crossgenre success. What, if anything, about your process changed between romance and horror?

GUADAGNINO: It’s the same. There is a movie by Claire Denis called Trouble Every Day about vampires who love each other, and it’s such a horror movie, but at the same time, it’s a big love story. Horror is the closest thing to love.

ANDERSON: Exactly.

GUADAGNINO: Because it’s visceral.

ANDERSON: What does it mean to capture desire as a filmmaker?

GUADAGNINO: It’s invisible, so if I manage to get there, then I’m doing my job properly, because film is always about what is invisible. It’s never about what is in front. So it’s a task. It’s the task of capturing the invisible.

ANDERSON: Let’s talk about your Desire Trilogy.

GUADAGNINO: That was a journalistic invention. I improvised because I had to find something to say when we were doing the first round of press for Call Me by Your Name. I didn’t want people to think that it was the trilogy of rich people. That’s why I said it’s the trilogy of desire. But I think I only do movies about desire in general.

ANDERSON: How did it feel directing an opera?

GUADAGNINO: That was a real disaster.

ANDERSON: Okay, great! [Laughs]

GUADAGNINO: I always wanted to make an opera, but I didn’t know anything about it, and I got this job at the Teatro Filarmonico in Verona, which is not the outdoor arena, but the indoor one. I was opening the season with Falstaff by Giuseppe Verdi and [Arrigo] Boito, and I knew nothing. I kept pushing forward the moment of preparing myself for it and basically I had to do it. I realized almost at the end that I had ten days of rehearsals with the singers, because that’s what they give you. I thought I was going to have like two months, not ten days. Then I made the mistake of hiring people from cinema to do costumes and design, and they didn’t know anything about theater either. So it was a disaster, but every endeavor, even when you’re good, like you Jonathan, sometimes you have to fail. I’m happy to have failed in the opera. It took me out of wanting to do more opera because it’s really complicated and I don’t want to fail.

ANDERSON: I always find failure the most exciting moment, because ultimately it feels like you could lose everything. I sometimes thrive on that moment. I like that it all could evaporate.

GUADAGNINO: Me too. Every day.

ANDERSON: Both Call Me by Your Name and Bones and All were adapted from literary sources. What makes a text a good candidate for an adaptation?

GUADAGNINO: A book is a great place to start for a movie if the book allows you to betray it. André Aciman, the author of Call Me by Your Name, was great in accepting the betrayals that we made of his text, which was a renowned book.

ANDERSON: A random question for you. When I think of America, I’m thinking of where we are today and what can be done, and I think one thing that could change in both Europe and America is this idea of forgiveness. As an image maker and as someone who portrays life, what do you think would help things globally at the moment?

GUADAGNINO: The sudden collapse of social media. If there were something, a bug that destroys it all, that would be a great step forward for humanity.

ANDERSON: Okay, good. When you listen to the news at the moment, it’s like, “How could I fix it?” And I feel like, if people would forgive each other, it might be easier.

GUADAGNINO: I agree with you. But again, social media is unforgiving. It’s all about narcissism. I think that listening is more important.

ANDERSON: So my last question is, we’ve been working together over the last couple of months on a very exciting project, which is called Challengers. I wanted to know what it was like to work with Zendaya?

GUADAGNINO: She is a remarkable filmmaker. She is a woman in command and at the same time, she is totally ready to become, to change, to be convinced to do something different. She’s super smart. I truly admire Zendaya, but I truly admire my costume designer as well.

ANDERSON: [Laughs] Well, Luca, thank you so much for taking the time for us to do this very formal conversation.

GUADAGNINO: I love formal conversation, but I’ll call you on the phone later for a less formal one. Okay?