Lev Kalman and Whitney Hornâ??s Permanent Vacation

The opening of Whitney Horn and Lev Kalman’s L for Leisure could have been lifted from a VHS tape of a well-remembered Southern California vacation: luxurious, panning shots of sun-soaked mountain vistas, crashing waves, and lush palm fronds. But a more exacting feeling that the film, shot in 16mm over the course of five years, ekes out is the buoyant, escapist rush of youthful freedom. Structured into a series of vignettes around the world (including Mexico, Provence, Long Island, and Iceland), L for Leisure follows a group of grad students in states of repose over various vacations from 1992 to 1993, drinking beers, taking naps, and, as grad students are wont to, getting deep into philosophical and ideological discourse.

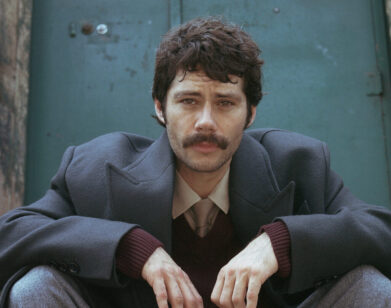

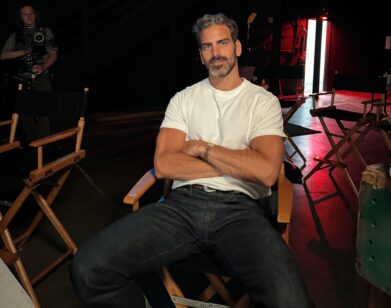

The California-based filmmaking duo (Kalman in San Diego; Horn in San Francisco) first met as undergraduates at Columbia. Their previous film, 2009’s Blondes in the Jungle, was a metaphysical study of a troupe of young WASPs search for enlightenment and adventure in the Honduran tropics, and L for Leisure is a companion travel piece, using found-footage-like visuals, stilted dialogue, awkward encounters, and a chilled out soundtrack to construct a period piece colored by our memories of the past.

Currently at work on their next film, an 1890s-set Western titled Two Plains & a Fancy (“about three tourists from the city going to New Mexico and Colorado and looking for the best hot spring spas in the country,” Kalman says), Interview spoke to the filmmakers last week in advance of the film’s opening, which will be held at the IFP Made in NY New York Media Center tonight. While we waited for the pair to dial in, synthy jazzy hold Muzak played on the line. It was the perfect way to begin the conversation.

COLLEEN KELSEY: Doing a film in this style and era is really an exercise in aesthetics. What was the genesis in selecting this time frame?

LEV KALMAN: I think a way that’s useful for us to talk about what we’re doing, it being a period piece, is that at no point do we want people to think, “Oh, wow. Was this made in the ’90s?” It’s us pinpointing certain things that we associate with the ’90s—facts of the ’90s and styles from the ’90s—that all create this world. It should look almost more like a historic reenactment on TV or something, where there are flaws. It should feel like people now describing certain things that they find interesting about that time. That’s the unfinished or specific aspect of our filmmaking, where there’s this tension between it looking like us recreating certain moments, and us approaching or simulating certain moments.

KELSEY: There’s definitely a dream-like quality to certain scenes, like reconstructed memories. How extensive was the research for this?

KALMAN: I guess more than you’d think. [laughs] We end up reading a lot. That’s a way we can prepare for the movie, obviously watching a lot of television and a lot of film and going back to our own memory. It’s often a process of being like, “Well, it’s cool that we now know this about the L.A. riots or something, but that doesn’t quite belong in the movie.” It’s not supposed to be a demonstration of our knowledge. Another example is that we’re making a Western right now; we’re writing one. We’re doing tons of reading and thinking and learning all of these facts. We’re like, “Wow. One percent of these are gonna be in the movie.” We’re not trying to teach people about the past. We’re trying to get our heads into that world.

KELSEY: Well, it’s interesting what you select to highlight. Early in the film, in the Laguna Beach segment, there’s the guy rolling up on rollerblades on the beach with a bottle of Snapple, which is such a ’90s trope. It’s not a nostalgic film, but nostalgia is integrated into it. How did you approach the friction of that?

KALMAN: I don’t feel like it’s a nostalgic film, but there are certain things. We started the movie five years ago. At that time, not as much, but by now certainly, the “I love the ’90s” thing has come and gone in a major way. There’s plenty of films that have been set in the ’90s. For all I know, there’s sitcoms now that are set in the ’90s, like, “Oh, remember MC Hammer?” or something like that. We were already training ourselves to be bored by those jokes early on, and instead, tried to find things that were a little bit weirder. With the Snapple, we really got into the idea of every scene having a signature beverage and that helping us define the characters. [laughs] There’s this thing about the ’90s, which is that these premium-ish beverages started to arrive. Mineral water and Snapple and all these things that are now mass-produced, like Dasani, feel like, “Oh, that’s the commercial, mass-produced bottled water.” When those things were coming out, they had this air of prestige. I was talking to somebody who said that when she was growing up, she would go to Costco because they had San Pellegrino, and it felt so classy to be going there and be buying your San Pellegrino and your Evian by the bulk. Suddenly, all these things that you would only see in movies were now available in small towns. You could get to them. That’s the feeling of the Snapple and the mineral water later on that’s this new, trendy, drink.

KELSEY: Or the novelty of Crystal Pepsi or whatever, which has its moment later on in the film.

KALMAN: Exactly.

KELSEY: Also something that really struck me was the amazing, beautiful environmental vistas juxtaposed with the events of each location. How do you determine the balance between the two?

KALMAN: We’re always trying to create characters that are relatable and tell a story, and then pull the viewer out of it and have them sit at a distance. Not only the reality of the space that they’re in, but also the conditions of making the movie in the sense about it being an imperfect recreation: the awkwardness, the telescoping back and forth between those different [scenes]. A method that we started using a while ago is that when we’re shooting, usually we’ll finish the narrative scene, and then Whitney, who’s the cinematographer, will just start photographing the world around there. I’ll also be picking up sounds. In other movies, if they have a gorgeous vista, they might incorporate it into the drama, to be motivated by the characters somehow. Where instead, what we do, as you said, is juxtapose. We hard break, “Here’s the story,” and “Break, here’s the location.” Then, they can sometimes comb in and out of each other. But in general, it’s like, “Nope. The landscape doesn’t care about this character. It doesn’t care about the story. Let’s look at it for a while.”

KELSEY: And for the dialogue, which is also very structured—a lot of these exchanges consist of heady intellectual and philosophical discourse. I assume those are pretty tightly scripted.

KALMAN: Oh, yeah. Sometimes they’re scripted more or less on the spot, or sometimes they’re prepared very much in advance. The nature of working in film, but also the very specific things we’re trying to get out of those scenes, they don’t allow for improv. We really drill the actors about getting those moments exactly as written.

KELSEY: I don’t want to use the word “satire,” but I think there’s definitely a self-awareness and a tongue-in-cheek element to these long, grandiose intellectual discussions, contextualized in the cheesiness of era’s visual look. But they appear from a very genuine place.

KALMAN: It’s funny that you also hesitated at “satire.” We just wish there was another word that can describe the awareness that what’s going on here is funny, but that we’re not smart enough to know our way out of it. It’s not coming from this position of, “Oh, isn’t it obvious what’s wrong with this?” Instead, we know that there’s something wrong with this, and we want to share that. We know there’s something funny about it. We know there’s something weird about what’s going on here, but we’re inside of it, too.

KELSEY: There’s definitely a thread of excess, of taking the time to luxuriate in these conversations. But also, at the same time, the film is structured during vacation periods, so excess and pleasure are kind of a given. How did you decide that these in-between periods were going to be the focus of the film?

KALMAN: I think it goes exactly with what you were saying about excess. If we’re interested in leisure time, then we have to make a movie where it wouldn’t keep getting edited out. [laughs] How can we keep the focus on the thing, when narrative economy or would always be like, “We get it, alright, relaxing. Now let’s move on to when the shit happens!?” These characters, not only are they on vacation, but they’re not good at being on vacation. It’s not like them hiking or mountaineering. They’re not pro tourists. They’re kind of bad at it. It’s the limit of trying to relax their brains and their bodies and trying to find these new ways of existing.

The way that the movie is structured is trying to find ways to exist on that time, not just showing that one scene ends with a nap, but a few scenes—making sure that we can give things that you might cut out of your biography and give it a form that can be held upright. That’s also why, for example, we get to be excessive with the music video-y parts of the movie. I really like how, especially when I watch it with an audience, how the water-skiing scene goes on for maybe a minute and a half longer than it should. We’re not trying to rush here and be like, “Nice, we nailed it.” Instead, we’re like, “Nope, let’s chill out here and do this music scene for a while.”

KELSEY: Tell me a little bit about the soundtrack.

KALMAN: It was all composed by John Atkinson, who’s a friend of ours, and who we’ve been working with in one way or another practically since college. He’s been involved in the movie since the very beginning, sending us little sketches. He’s in a dance noise band called Aa, but on the side, had started to do these really minimal ambient things. So we were like, “Great! You’re also going into this relaxed mode.” Our instruction to him was often like, “Oh, we need this kind of vibe or whatever. But again, replicate what we’re doing, don’t create a perfect copy of this. Instead, filter it through your process,” which I think in his case, involves some synth stuff and also some field recording and mixing that. “If you were going to make music the way you do already, how would you deal with these feelings?” It should sound like somebody on a laptop now, but trying to reminisce about his own memory about the ‘90s, his own feelings about vacation.

KELSEY: Would you say that in your movies, you’re interested in the moments that are omitted, or, usually not a part of a cinematic narrative? The in-between things that normally wouldn’t be seen as compelling enough to be on screen?

KALMAN: That’s definitely the way we approach movies. [laughs] I think that we work towards our strengths or something. There’s moments that are really done well in other people’s movies. And then, there’s things that we might notice in their films or we might notice on TV shows, or our lives where it’s like, “That’s never in a movie,” or “That kind of moment…” We’re like, “How can we build a movie around that?” We’re pretty good about catching those little things. The one I always think about is, in L for Leisure, every scene where people meet includes them hugging and saying, “Hi,” and getting themselves settled. That’s the part that’s always written out. A compelling script instead would have their entrance itself be dramatic and filled with the seed of the conflict already. Instead, we’re just letting those more mundane things happen, giving everyone their time to have their drink and put it right back down.

L FOR LEISURE OPENS TONIGHT AT THE INDEPENDENT FILMMAKER PROJECT’S (IFP) MADE IN NY NEW YORK MEDIA CENTER, 30 JOHN STREET, BROOKLYN. A Q&A WITH THE FILMMAKERS AND CAST WILL FOLLOW THE SCREENING. FOR MORE INFO AND TICKETS, VISIT THE IFP SITE.